Numantia, Cervantes, Vicksburg, Terrorists ______

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Vaccaei, a People Whose Existence Is Hardly Remembered in History

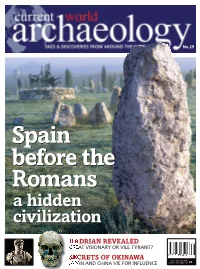

current world archaeology No.29 Japan • Pintia, Spain • Hadrian's Rome Rome Hadrian's SpainSpain • Southeast Asia beforebefore thethe • Corfu RomansRomans aa hiddenhidden civilizationcivilization HADRIAN REVEALED GREAT VISIONARY OR VILE TYRANT? Issue 29 SECRETS OF OKINAWA No.29 June/July 2008 JAPAN AND CHINA VIE FOR INFLUENCE www.archaeology.co.uk £4 001_Cover_CWA29 final UK.indd 1 13/5/08 11:33:20 Pintia Fortunes of a pre-Roman city in Hispania Pintia was a thriving Iron Age city in North Central Spain. At its dawn, around the 5th century BC, it was part of the Vaccean culture, an Iron Age people Below Necropolis of with Celtic links whom scholars believe crossed into Spain from Central Las Ruedas at Pintia. Europe. In the 3rd century BC, the area came under attack from Hannibal, The field of tombstones is made up of unworked and within 200 years it had beeen absorbed into Roman Iberia. Pintia's vast limestone blocks hewn necropolis is proving a rich source of information about this relatively little from the nearby quarry. The stones are of various known Vaccean culture. Here, excavation directors Carlos Sanz Minguez sizes, and up to a and Fernando Romero Carnicero, reveal the site’s latest finds. maximum height of 1m. current world 22 archaeology 29 022-029_Spain2_CWA29.indd 22 14/5/08 15:20:23 Spain 1. Residential Area 3. Artisan Neighbourhood 2. Outskirts (outside the walls) 4. Cremation Area 5 4 6 1 2 3 Left & below A photographic aerial view and geological survey map of the area showing the positions of the main sites. -

The Siege of Numantia Info About the Play from Wikipedia

University Theatre Fall 2016 The Siege of Numantia Info about the play from Wikipedia Guest Director – David Lozano, Artistic Director Cara Mia Theatre Will be staged with movement and Mexican-style masks Adaptation and Translator - Fernando Contreras Written by Miguel de Cervantes Characters Romans: Scipio, Jugurtha, Caius Marius, Quintus Fabius Numantines: Theogenes, Caravino, Marquino, Marandro, Leonicio, Lira Allegories: Spain, the Duero River and three tributaries, War, Pestilence, Hunger, Fame Original language Spanish Subject the fall of the Spanish city of Numantia to the Romans Genre historical tragedy Setting Numantia, 133 BCE The Siege of Numantia (Spanish: El cerco de Numancia) is a tragedy by Miguel de Cervantes set at the siege of Numantia. The play is divided into four acts. The work was composed circa 1582 and was apparently very successful in the years before the advent of Lope de Vega as playwright. It remained unpublished until the eighteenth- century. Since then, it has been hailed by many as a “rare specimen of Spanish tragedy” and even as the best Spanish tragedy not only from the period before Lope de Vega, but of all its literature. Some critics have seen resemblances between Cervantes' tragedy and Aeschylus's The Persians, while others reject that the play is a conventional tragedy. … Plot In the first act, Scipio appears with his generals in the Roman camp before Numantia. He explains that this war has been going on for many years and that the Roman Senate has sent him to finish the task. He reprimands his troops, whose martial spirit has begun to be superseded by the pleasures of Venus and Bacchus. -

Linguistic and Cultural Crisis in Galicia, Spain

University of Massachusetts Amherst ScholarWorks@UMass Amherst Doctoral Dissertations 1896 - February 2014 1-1-1991 Linguistic and cultural crisis in Galicia, Spain. Pedro Arias-Gonzalez University of Massachusetts Amherst Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarworks.umass.edu/dissertations_1 Recommended Citation Arias-Gonzalez, Pedro, "Linguistic and cultural crisis in Galicia, Spain." (1991). Doctoral Dissertations 1896 - February 2014. 4720. https://scholarworks.umass.edu/dissertations_1/4720 This Open Access Dissertation is brought to you for free and open access by ScholarWorks@UMass Amherst. It has been accepted for inclusion in Doctoral Dissertations 1896 - February 2014 by an authorized administrator of ScholarWorks@UMass Amherst. For more information, please contact [email protected]. LINGUISTIC AND CULTURAL CRISIS IN GALICIA, SPAIN A Dissertation Presented by PEDRO ARIAS-GONZALEZ Submitted to the Graduate School of the University of Massachusetts in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of DOCTOR OF EDUCATION May, 1991 Education Copyright by Pedro Arias-Gonzalez 1991 All Rights Reserved LINGUISTIC AND CULTURAL CRISIS IN GALICIA, SPAIN A Dissertation Presented by PEDRO ARIAS-GONZALEZ Approved as to style and content by: DEDICATION I would like to dedicate this dissertation to those who contributed to my well-being and professional endeavors: • My parents, Ervigio Arias-Fernandez and Vicenta Gonzalez-Gonzalez, who, throughout their lives, gave me the support and the inspiration neces¬ sary to aspire to higher aims in hard times. I only wish they could be here today to appreciate the fruits of their labor. • My wife, Maria Concepcion Echeverria-Echecon; my son, Peter Arias-Echeverria; and my daugh¬ ter, Elizabeth M. -

Gis and Roman Ways Research in Hispania. Abstract

GIS and roman ways research in Hispania José Luis Vicente González GIS AND ROMAN WAYS RESEARCH IN HISPANIA. José Luis Vicente González Forestry engineer. GIS consultant Milles de la Polvorosa (Zamora, SPAIN). [email protected] ∗ Translation from the original Spanish text made by the author with the invaluable help of Google Translator. If you can understand without trouble the content of the communication, thank the technicians from Google; otherwise, download the blame on the speaker and its pitiful knowledge of English grammar. ** This paper was excerpted from a longer article published in the Proceedings of the “Tenth International Conference of Hispanic Roads", held in Madrid in June 2010. The original text (in Spanish) is available in the next URL: http://www.jlvg.es/Publicaciones.asp ABSTRACT Geographic Information Systems are a very powerful tool to explore the configuration of the existing road network in times past, but the possibilities in this sense hardly been exploited so far. The communication is intended to describe a GIS project specifically designed to investigate the development of road network in the western Northern Plateau of Spain during the Ancient Age. In the first part of the same, details the project structure and the content and usefulness of the different layers of information in it. Finally, we discuss the results to the present time by the research, including the location of the paths of the main Roman routes that defined the current province of Zamora and neighboring areas, the situation of the mansiones and mutationes that mark out the roads, and the location of the main quarries used to build them. -

Kentucky Foreign Language Conference, April 19-21, 2012

Emily S. Beck 479 Historiographical Approaches to Iberian Multiculturalism and Castilian Imperialism during the Siglo de Oro Emily S. Beck College of Charleston The expansion of Rome beyond the Italic Peninsula and the policies of conquest and colonization practiced by the ancients were historical touchstones for many authors of the so- called Golden Age to reexamine the hegemony and Imperial legacy of Castile.1 In particular, the bloody siege of the Iberian settlement of Numantia (Numancia in Hispanic letters) in 133 BCE by the Roman army was a pivotal event in Iberian history. Retellings of this siege and the Roman conquest of the Iberian Peninsula provided a lens through which writers might examine the strategies of imperial military powers, consider characteristics of the pre-Romanized Iberian tribes, analyze the behavior of captive civilians during conquest, and evaluate the human and economic toll of warfare. Although many Ancient Roman attacks were met with comparatively little resistance by the indigenous Iberians who lacked the military prowess of the conquerors, the blockade on the settlement of Numantia, located in the central peninsula near present-day Soria, continued for years and revealed weaknesses in the discipline and strategy of the Roman military.2 The willingness of pre-Romanized inhabitants of the small settlement of Numantia to commit suicide rather than submit to the Roman Army is a gripping tale that continues to move readers today.3 Reassessing depictions of confrontations and other retellings of the conquest of Ancient Iberia by the Romans reveal approaches to historiography, multiculturalism, and 1 In the late sixteenth century, reports arriving from the American continent and Castilian colonies were increasingly mixed about Imperial successes abroad. -

The Celts in Iberia: an Overview

The Celts in Iberia: An Overview Alberto J. Lorrio, Universidad de Alicante Gonzalo Ruiz Zapatero, Universidad Complutense de Madrid Abstract A general overview of the study of the Celts in the Iberian Peninsula is offered from a critical perspective. First, we present a brief history of research and the state of research on ancient written sources, linguistics, epigraphy and archaeological data. Second, we present a different hypothesis for the "Celtic" genesis in Iberia by applying a multidisciplinary approach to the topic. Finally, on the one hand an analysis of the main archaeological groups (Celtiberian, Vetton, Vaccean, the Castro Culture of the northwest, Asturian-Cantabrian and Celtic of the southwest) is presented, while on the other hand we propose a new vision of the Celts in Iberia, rethinking the meaning of "Celtic" from a European perspective. Keywords Celts, Iberian Peninsula, Iron Age, Celtiberians, Indo-European. 1. Introduction Textbooks on European prehistory published during the last seventy-five years confirm that ever since the first theories were formulated at the beginning of the nineteenth century, the Celts have played a crucial role in studies of European protohistory. The Celts have even been accused of taking over Europe during the Iron Age, through the cultures of Hallstatt and La Tène. Any conclusions drawn by European historiography about the Celts have been based on the image conjured up by Classical sources and the archaeological and cultural evidence collected at La Tène. It was only during the mid 1980s that scholars began to debate this issue and started to break away from the conventional established image of the Celts (Collis 2003; Ruiz Zapatero 1993, 2001). -

Diane Bani-Esraili

Cervantes’ El Cerco de Numancia: An Argument Based on Blood Based Determination of Hispanidad Diane Bani-Esraili 64 I. Introduction and Statement of Purpose de Numancia (1582) is marked by mass brutality, bloodshed, and death. Cervantes portrays bodily suffering throughout the work—from to the scene of a father killing his helplessly compliant wife and every last Numantine enemy already dead and the city engulfed in “un rojo lago”1 of blood. Blood pervades Numancia; indeed, it is the principal trope. In This paper will discuss those different meanings and associations and, thereby, establish the centrality of the role of blood in early modern Spanish society. Based on that foundation, this paper will go on to explain how Cervantes uses the legendary point of origin of the Spanish nation— the siege of Numantia during the Roman conquest of the Iberian Peninsula in the second century BCE—to reevaluate the relationship between blood and hispanidad. Through his play Cervantes discredits the prevalent notion of his time that limpieza de sangre (purity of blood) is the determinant of hispanidad. This paper will demonstrate that while he discredits limpieza de sangre as the determinant of hispanidad, he still Holy Blood or sacramental embodiment of the Eucharist that is the true, and only true, link Spaniards can claim to their Numantine it is Holy Blood—voluntary, Christian action—rather than purity of blood—predetermined accident of birth—that determines hispanidad. 65 II. Historical Context and Discourses of Blood It is important to understand the social and religious historical context by which Cervantes was influenced and from which Numancia and its anti-mainstream argument about blood and hispanidad emerge.2 role in both social and religious arenas (which, by nature, often overlap) and multiple and simultaneous discourses of blood existed. -

Celtiberians

SBORNÍK PRACÍ FILOZOFICKÉ FAKULTY BRNĚNSKÉ UNIVERZITY STUDIA MINORA FACULTATIS PHILOSOPHICAE UNIVERSITATIS BRUNENSIS N 12, 2007 Václav BLAžEK CELTIBERIAN 1. Historical witness 2. Origin of the ethnonym 3. Most important inscriptions 4. Grammatical sketch 4.1. Historical phonology 4.2. Historical morphology 4.2.1. Nominal declension in context of other old Celtic languages 4.2.2. Pronouns 4.2.3. Numerals 4.2.4. Verbs 4.2.5. Prepositions, prefixes & preverbs 4.2.6. Conjunctions & negation. 5. Basic bibliography. 1. Historical witness From the antique authors the most detailed information about Celtiberia and its inhabitants was mediated by Strabo [III, 4; translation Horace L. Jones]: (§12) “Crossing over the Idubeda Mountain, you are at once in Celtiberia, a large and uneven country. The greater part of it in fact is rugged and river-washed; for it is through these regions that the Anas flows, and also the Tagus, and the several rivers next to them, which, rising in Celtiberia, flow down to the western sea. Among these are Durius, which flows part Numantia and Serguntia, and the Bae- tis, which, rising in the Orospeda, flows through Oretania into Baetica. Now, in the first place, the parts to the north of the Celtiberians are the home of the Ve- ronians, neighbours of the Cantabrian Coniscans, and they too have their origin in the Celtic expedition; they have a city, Varia, situated at the crossing of the Iberus; and their territory also runs contiguous to that of the Barduetans, whom the men of today call Bardulians. Secondly, the parts on the western side are the home of some of the Asturians, Callaicans, and Vaccaeans,and also of the Vettonians and Carpetanians. -

The Celts in the West. Italy and Spain

THE GREATNESS AND DECLINE OF THE CELTS CHAPTER III (part 1) THE CELTS IN THE WEST. ITALY AND SPAIN I THE BELGÆ IN ITALY FROM the end of the third century onwards, the Belgæ are to be found taking a part in every movement which occurs in the Celtic world. The other Gauls seek their help for special purposes, defend themselves against them, or follow them. While they are trying to carve out an empire for themselves on the Danube and in the East, new bodies descend on Italy and Spain. The political events of the second century bring the Celts into contact with a great organized state, a creator of order in its own fashion, the Roman Republic. The history of these peoples is henceforward the story of their struggle with Rome, in which, from the west of the Mediterranean to the east, they are vanquished, and it is through the ups and downs of that story that we catch glimpses of their internal life. Yet another danger threatens them. To the north, over an area of the same extent, the Celtic world has at the same time to suffer encroachments and advances on the part of men of inferior civilization, speaking another language and forming another group, who have begun to move in the wake of the Belgæ, a hundred years after them. These are the Germans, whose name has already turned up in the course of this history, in Ireland, then in Italy, and finally in Spain, though in this last country its meaning is uncertain. [Livy, x, 107; Polyb., ii, 19, 1.] A century after the first invasion, the peace of the Gauls of the Po valley was disturbed by the arrival of a large body of men from over the Alps. -

Celtiberians: Problems and Debates

e-Keltoi: Journal of Interdisciplinary Celtic Studies Volume 6 The Celts in the Iberian Peninsula Article 8 6-22-2005 Celtiberians: Problems and Debates Francisco Burillo Mozota Centro de Estudios Celtibéricos de Segeda, Seminario de Arqueología y Etnología Turolense, Facultad de Humanidades y Ciencias Sociales, Teruel Follow this and additional works at: https://dc.uwm.edu/ekeltoi Recommended Citation Mozota, Francisco Burillo (2005) "Celtiberians: Problems and Debates," e-Keltoi: Journal of Interdisciplinary Celtic Studies: Vol. 6 , Article 8. Available at: https://dc.uwm.edu/ekeltoi/vol6/iss1/8 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by UWM Digital Commons. It has been accepted for inclusion in e-Keltoi: Journal of Interdisciplinary Celtic Studies by an authorized administrator of UWM Digital Commons. For more information, please contact open- [email protected]. Celtiberians: Problems and Debates Francisco Burillo Mozota Centro de Estudios Celtibéricos de Segeda Seminario de Arqueología y Etnología Turolense Facultad de Humanidades y Ciencias Sociales, Teruel Abstract The Celtiberians are undoubtedly the people from ancient Hispania that have attracted the highest level of interest among scholars within the different disciplines (e.g. archaeologists, linguists, and historians). This critical review of the post-1998 literature on the Celtiberians has been divided into nine sections: the meaning of the word "Celtiberians", the Celtiberian language, the formation of the Celtiberian culture, population, Celtiberian migrations, economy, the study of rituals through an examination of ceramics, mortuary rituals, and Celto-mania and the Celtiberians. Keywords Celtiberians, Iberian Peninsula, Celts, Urnfield Culture, Celtiberian language, City-states 1. Foreword The length of this paper and the diversity of issues it addresses have led reviewers to recommend the inclusion of "a brief indication of the structure of the article and the range and order of coverage". -

1 New Perspectives on Byzantine Spain

New perspectives on Byzantine Spain: The Discriptio Hispaniae Oriol Olesti Vila, Ricard Andreu Expósito (Universitat Autònoma de Barcelona) and Jamie Wood (University of Lincoln) Abstract The Discriptio Hispaniae is a passage from the Geometry of Gisemundus, also entitled Ars Gromatica Gisemundi (AGG), a medieval treatise of agrimensura written by an unknown author, probably a monk known as Gisemundus who had some agrimensorial experience. The work was compiled around 800 A.D. by collecting passages of a range of sizes, from just a few words to several pages, extracted from ancient and medieval sources. Although modern research into Roman agrimensorial texts has admitted the importance of the AGG, its corrupt condition has not invited sustained analysis. The passage now known as the Discriptio Hispaniae, a short section from chapter three of the second book of the AGG entitled III De segregatione provinciarum ab Augustalibus terminis, is particularly interesting for the information that it provides concerning the territorial division of Hispania in late antiquity. This article presents an edition and English translation of the Discriptio Hispaniae and argues that the most likely point of origin for the Discriptio Hispaniae is during the Byzantine occupation of parts of southern Spain during the second half of the sixth century and the first quarter of the seventh century. We suggest that the Discriptio Hispaniae was preserved because the Byzantine autorities were keen to keep on record information about the borders of the province of Carthaginensis, perhaps the main theme in the text. Keywords Byzantine, Spain, Iberian Peninsula, Justinian, Manuscripts Introduction The Discriptio Hispaniae is a passage from the Geometry of Gisemundus, also entitled Ars Gromatica Gisemundi (AGG), a medieval treatise of agrimensura written by an unknown author, probably a monk known as Gisemundus who had some agrimensorial experience. -

The Presence of the Roman Army in North-Western Hispania: New Archaeological Data from Ancient Asturias and Galicia

JOSÉ MANUEL COSTA-GARCÍA, ANDRÉS MENÉNDEZ BLANCO, DAVID GONZÁLEZ ÁLVAREZ, MANUEL GAGO MARIÑO, JOÃO FONTE, REBECA BLANCO-ROTEA AND VALENTÍN ÁLVAREZ MARTÍNEZ 903 The Presence of the Roman Army in North-Western Hispania: New Archaeological Data from Ancient Asturias and Galicia JOSÉ MANUEL COSTA-GARCÍA, ANDRÉS MENÉNDEZ BLANCO, DAVID GONZÁLEZ ÁLVAREZ, MANUEL GAGO MARIÑO, JOÃO FONTE, REBECA BLANCO-ROTEA AND VALENTÍN ÁLVAREZ MARTÍNEZ The Presence of the Roman Army in North-Western Hispania: New Archaeo- logical Data from Ancient Asturias and Galicia ZUSAMMENFASSUNG forschung wurde ein wenig kostenintensives methodisches Vorge- Im äußersten Nordosten der Iberischen Halbinsel wurden in den hen angewendet und historische und moderne Luft- bzw. Satelli- letzten Jahrzehnten mehrere Römerlager entdeckt. Die meisten tenaufnahmen sowie LiDAR, GIS-Software und konventionelle dieser Fundstellen stehen vornehmlich in Zusammenhang mit Au- Prospektion kombiniert sowie auch lokale Ortsnamen und mündli- gustus‘ Kriegen gegen indigene Gemeinschaften, die von antiken che Überlieferung berücksichtigt. Da aus dem Arbeitsgebiet bisher Autoren als Cantabri und Astures genannt werden. nicht viele castra aestiva bekannt sind, ermöglichen es diese Fund- Ziel dieses Beitrages ist es, einige der jüngst in den spanischen Re- stellen nun, die Aktivitäten der römischen Armee im Nordwesten gionen León, Asturien und Galicien sowie im Norden Portugals der Iberia während der ersten Jahre des Prinzipats besser zu ver- entdeckten archäologischen Stätten zu präsentieren. Für ihre Er- stehen. Fig. 1: Roman military sites in North-Western Iberia. Huerga de Frailes (1), Picu Viyao (2), Moyapán (3), El Chao (4), La Resieḷḷa (5), A Granda das Xarras (6), A Recacha (7), El Mouru (8), Valbona (9), El Xuegu la Bola (10), Cueiru (11), A Penaparda (12), El Pico el Outeiro (13), A Pedra Dereta (14), El Chao de Carrubeiro (15), A Serra da Casiña (16), Monte da Modorra (17), Monte da Chá (18), Cabianca (19), O Monte dos Trol- los (20), O Cornado (21), Campos (22) (© authors).