Numantia : a Tragedy

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Esther Fernández

Updated November, 2016 Esther Fernández Department of Spanish Portuguese and Latin American Studies Rice University || 6100 Main MS-34 Houston, Texas 77005 Phone: (917) 783 – 7702 || E-mail: [email protected] ACADEMIC EMPLOYMENT 2015 – Rice University. Assistant Professor, Department of Spanish and Portuguese & Latin American Studies. 2008 – 2015 Sarah Lawrence College. Assistant Professor, Department of Modern and Classical Languages and Literatures. 2011 – 2013 Cornell University. Visiting Assistant Professor, Department of Romance Studies. 2005 – 2008 Grinnell College, Assistant Professor, Department of Spanish. 1999 – 2005 University of California, Davis. Associate Instructor, Department of Spanish and Portuguese. EDUCATION 2005 Ph.D. University of California, Davis. Major field of study in Early Modern Literature. 2001 M.A. University of California, Davis. Peninsular and Latin American Literature. 1999 B.A. Wheaton College. Hispanic Studies and French Literature. PUBLICATIONS SINGLE-AUTHOR MONOGRAPHS In Progress Material performances: Staging the Divine and the Spectacular in Early Modern Iberia. 2009 Eros en escena: el erotismo en el teatro del Siglo de Oro. Delaware: Juan de la Cuesta. EDITED VOLUMES Forthcoming El teatro clásico en su(s) cultura(s): de los Siglos de Oro al siglo XXI. Actas selectas del XVII congreso de la Asociación Internacional de Teatro Español y Novohispano de los Siglos de Oro (AITENSO) . Co-edited with Alejandro García-Reidy and José Miguel Martínez Torrejón. New York: Hispanic Seminary of Medieval Studies. Under review The Image of Elizabeth I in Early Modern Spain. Co-edited with Eduardo Olid-Guerrero. Lincoln: Nebraska Univeristy Press. 2014 Diálogos en las tablas: Últimas tendencias de la puesta en escena del treatro clásico español. -

Cervantes and the Spanish Baroque Aesthetics in the Novels of Graham Greene

TESIS DOCTORAL Título Cervantes and the spanish baroque aesthetics in the novels of Graham Greene Autor/es Ismael Ibáñez Rosales Director/es Carlos Villar Flor Facultad Facultad de Letras y de la Educación Titulación Departamento Filologías Modernas Curso Académico Cervantes and the spanish baroque aesthetics in the novels of Graham Greene, tesis doctoral de Ismael Ibáñez Rosales, dirigida por Carlos Villar Flor (publicada por la Universidad de La Rioja), se difunde bajo una Licencia Creative Commons Reconocimiento-NoComercial-SinObraDerivada 3.0 Unported. Permisos que vayan más allá de lo cubierto por esta licencia pueden solicitarse a los titulares del copyright. © El autor © Universidad de La Rioja, Servicio de Publicaciones, 2016 publicaciones.unirioja.es E-mail: [email protected] CERVANTES AND THE SPANISH BAROQUE AESTHETICS IN THE NOVELS OF GRAHAM GREENE By Ismael Ibáñez Rosales Supervised by Carlos Villar Flor Ph.D A thesis submitted in fulfilment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy At University of La Rioja, Spain. 2015 Ibáñez-Rosales 2 Ibáñez-Rosales CONTENTS Abbreviations ………………………………………………………………………….......5 INTRODUCTION ...…………………………………………………………...….7 METHODOLOGY AND STRUCTURE………………………………….……..12 STATE OF THE ART ..……….………………………………………………...31 PART I: SPAIN, CATHOLICISM AND THE ORIGIN OF THE MODERN (CATHOLIC) NOVEL………………………………………38 I.1 A CATHOLIC NOVEL?......................................................................39 I.2 ENGLISH CATHOLICISM………………………………………….58 I.3 THE ORIGIN OF THE MODERN -

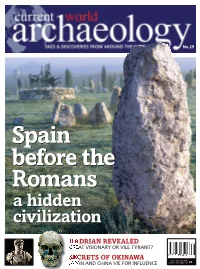

Vaccaei, a People Whose Existence Is Hardly Remembered in History

current world archaeology No.29 Japan • Pintia, Spain • Hadrian's Rome Rome Hadrian's SpainSpain • Southeast Asia beforebefore thethe • Corfu RomansRomans aa hiddenhidden civilizationcivilization HADRIAN REVEALED GREAT VISIONARY OR VILE TYRANT? Issue 29 SECRETS OF OKINAWA No.29 June/July 2008 JAPAN AND CHINA VIE FOR INFLUENCE www.archaeology.co.uk £4 001_Cover_CWA29 final UK.indd 1 13/5/08 11:33:20 Pintia Fortunes of a pre-Roman city in Hispania Pintia was a thriving Iron Age city in North Central Spain. At its dawn, around the 5th century BC, it was part of the Vaccean culture, an Iron Age people Below Necropolis of with Celtic links whom scholars believe crossed into Spain from Central Las Ruedas at Pintia. Europe. In the 3rd century BC, the area came under attack from Hannibal, The field of tombstones is made up of unworked and within 200 years it had beeen absorbed into Roman Iberia. Pintia's vast limestone blocks hewn necropolis is proving a rich source of information about this relatively little from the nearby quarry. The stones are of various known Vaccean culture. Here, excavation directors Carlos Sanz Minguez sizes, and up to a and Fernando Romero Carnicero, reveal the site’s latest finds. maximum height of 1m. current world 22 archaeology 29 022-029_Spain2_CWA29.indd 22 14/5/08 15:20:23 Spain 1. Residential Area 3. Artisan Neighbourhood 2. Outskirts (outside the walls) 4. Cremation Area 5 4 6 1 2 3 Left & below A photographic aerial view and geological survey map of the area showing the positions of the main sites. -

The Siege of Numantia Info About the Play from Wikipedia

University Theatre Fall 2016 The Siege of Numantia Info about the play from Wikipedia Guest Director – David Lozano, Artistic Director Cara Mia Theatre Will be staged with movement and Mexican-style masks Adaptation and Translator - Fernando Contreras Written by Miguel de Cervantes Characters Romans: Scipio, Jugurtha, Caius Marius, Quintus Fabius Numantines: Theogenes, Caravino, Marquino, Marandro, Leonicio, Lira Allegories: Spain, the Duero River and three tributaries, War, Pestilence, Hunger, Fame Original language Spanish Subject the fall of the Spanish city of Numantia to the Romans Genre historical tragedy Setting Numantia, 133 BCE The Siege of Numantia (Spanish: El cerco de Numancia) is a tragedy by Miguel de Cervantes set at the siege of Numantia. The play is divided into four acts. The work was composed circa 1582 and was apparently very successful in the years before the advent of Lope de Vega as playwright. It remained unpublished until the eighteenth- century. Since then, it has been hailed by many as a “rare specimen of Spanish tragedy” and even as the best Spanish tragedy not only from the period before Lope de Vega, but of all its literature. Some critics have seen resemblances between Cervantes' tragedy and Aeschylus's The Persians, while others reject that the play is a conventional tragedy. … Plot In the first act, Scipio appears with his generals in the Roman camp before Numantia. He explains that this war has been going on for many years and that the Roman Senate has sent him to finish the task. He reprimands his troops, whose martial spirit has begun to be superseded by the pleasures of Venus and Bacchus. -

Numantia, Cervantes, Vicksburg, Terrorists ______

Numantia, Cervantes, Vicksburg, Terrorists ____________________________ By William Eaton . though that cause was, I believe, one of the worst for which a people ever fought, and one for which there was the least excuse. I do not question, however, the sincerity of the great mass of those who were opposed to us. — U.S. Grant, writing, years later, about the Confederate surrender at Appomattox1 Ellos con duros estatutos fieros y con su extraña condición avara pusieron tan gran yugo a nuestros cuellos que forzados salimos de él y de ellos By harsh law and regulation, By such an alien greed driven; On our necks the hard yoke was laid; Orders and outrage we betrayed.2 1 Ulysses S. Grant, Memoirs, edited with notes by E.B. Long (De Capo Press, 1982). 2 History has left two distinct versions of Cervantes’ play, and neither of these is considered to be close to the original. There are also several titles, including El cerco de Numancia (The Siege of Numantia), La destruición de Numancia, and simply Numancia. In an effort to keep this epigraph to four lines and to have it represent Numancia, Cervantes’ play, as a whole, I have inserted into my translation information that comes from earlier and later in a Cervantes’ text. Below the entire stanza from the Cervantes text and from James Young Gibson’s translation (which scrupulously duplicates in English Cervantes’ Spanish verse forms). Dice que nunca de la ley y fueros del senado romano se apartara si el insufrible mando y desafueros de un cónsul y otro no le fatigara. -

Linguistic and Cultural Crisis in Galicia, Spain

University of Massachusetts Amherst ScholarWorks@UMass Amherst Doctoral Dissertations 1896 - February 2014 1-1-1991 Linguistic and cultural crisis in Galicia, Spain. Pedro Arias-Gonzalez University of Massachusetts Amherst Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarworks.umass.edu/dissertations_1 Recommended Citation Arias-Gonzalez, Pedro, "Linguistic and cultural crisis in Galicia, Spain." (1991). Doctoral Dissertations 1896 - February 2014. 4720. https://scholarworks.umass.edu/dissertations_1/4720 This Open Access Dissertation is brought to you for free and open access by ScholarWorks@UMass Amherst. It has been accepted for inclusion in Doctoral Dissertations 1896 - February 2014 by an authorized administrator of ScholarWorks@UMass Amherst. For more information, please contact [email protected]. LINGUISTIC AND CULTURAL CRISIS IN GALICIA, SPAIN A Dissertation Presented by PEDRO ARIAS-GONZALEZ Submitted to the Graduate School of the University of Massachusetts in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of DOCTOR OF EDUCATION May, 1991 Education Copyright by Pedro Arias-Gonzalez 1991 All Rights Reserved LINGUISTIC AND CULTURAL CRISIS IN GALICIA, SPAIN A Dissertation Presented by PEDRO ARIAS-GONZALEZ Approved as to style and content by: DEDICATION I would like to dedicate this dissertation to those who contributed to my well-being and professional endeavors: • My parents, Ervigio Arias-Fernandez and Vicenta Gonzalez-Gonzalez, who, throughout their lives, gave me the support and the inspiration neces¬ sary to aspire to higher aims in hard times. I only wish they could be here today to appreciate the fruits of their labor. • My wife, Maria Concepcion Echeverria-Echecon; my son, Peter Arias-Echeverria; and my daugh¬ ter, Elizabeth M. -

The Cambridge Companion to Cervantes Edited by Anthony J

Cambridge University Press 978-0-521-66321-2 - The Cambridge Companion to Cervantes Edited by Anthony J . Cascardi Frontmatter More information The Cambridge Companion to Cervantes Don Quixote de la Mancha (1605) is one of the classic texts of Western litera- ture and the foundation of European fiction. Yet Cervantes himself remains an enigmatic figure. The Cambridge Companion to Cervantes offers a compre- hensive treatment of Cervantes’ life and work, including his lesser known writ- ing. The essays, by some the most outstanding scholars in the field, cover the historical and political context of Cervantes’ writing, his place in Renaissance culture, and the role of his masterpiece, Don Quixote, in the formation of the modern novel. They draw on contemporary critical perspectives to shed new light on Cervantes’ work, including the Exemplary Novels, the plays and dramatic interludes, and the long romances, Galatea and Persiles. The vol- ume provides useful supporting material for students: suggestions for further reading, a detailed chronology, a complete list of his published writings, an overview of translations and editions, and a guide to electronic resources. © in this web service Cambridge University Press www.cambridge.org Cambridge University Press 978-0-521-66321-2 - The Cambridge Companion to Cervantes Edited by Anthony J . Cascardi Frontmatter More information © in this web service Cambridge University Press www.cambridge.org Cambridge University Press 978-0-521-66321-2 - The Cambridge Companion to Cervantes Edited by Anthony J . Cascardi Frontmatter More information THE CAMBRIDGE COMPANION TO CERVANTES EDITED BY ANTHONY J. CASCARDI © in this web service Cambridge University Press www.cambridge.org Cambridge University Press 978-0-521-66321-2 - The Cambridge Companion to Cervantes Edited by Anthony J . -

Gis and Roman Ways Research in Hispania. Abstract

GIS and roman ways research in Hispania José Luis Vicente González GIS AND ROMAN WAYS RESEARCH IN HISPANIA. José Luis Vicente González Forestry engineer. GIS consultant Milles de la Polvorosa (Zamora, SPAIN). [email protected] ∗ Translation from the original Spanish text made by the author with the invaluable help of Google Translator. If you can understand without trouble the content of the communication, thank the technicians from Google; otherwise, download the blame on the speaker and its pitiful knowledge of English grammar. ** This paper was excerpted from a longer article published in the Proceedings of the “Tenth International Conference of Hispanic Roads", held in Madrid in June 2010. The original text (in Spanish) is available in the next URL: http://www.jlvg.es/Publicaciones.asp ABSTRACT Geographic Information Systems are a very powerful tool to explore the configuration of the existing road network in times past, but the possibilities in this sense hardly been exploited so far. The communication is intended to describe a GIS project specifically designed to investigate the development of road network in the western Northern Plateau of Spain during the Ancient Age. In the first part of the same, details the project structure and the content and usefulness of the different layers of information in it. Finally, we discuss the results to the present time by the research, including the location of the paths of the main Roman routes that defined the current province of Zamora and neighboring areas, the situation of the mansiones and mutationes that mark out the roads, and the location of the main quarries used to build them. -

Kentucky Foreign Language Conference, April 19-21, 2012

Emily S. Beck 479 Historiographical Approaches to Iberian Multiculturalism and Castilian Imperialism during the Siglo de Oro Emily S. Beck College of Charleston The expansion of Rome beyond the Italic Peninsula and the policies of conquest and colonization practiced by the ancients were historical touchstones for many authors of the so- called Golden Age to reexamine the hegemony and Imperial legacy of Castile.1 In particular, the bloody siege of the Iberian settlement of Numantia (Numancia in Hispanic letters) in 133 BCE by the Roman army was a pivotal event in Iberian history. Retellings of this siege and the Roman conquest of the Iberian Peninsula provided a lens through which writers might examine the strategies of imperial military powers, consider characteristics of the pre-Romanized Iberian tribes, analyze the behavior of captive civilians during conquest, and evaluate the human and economic toll of warfare. Although many Ancient Roman attacks were met with comparatively little resistance by the indigenous Iberians who lacked the military prowess of the conquerors, the blockade on the settlement of Numantia, located in the central peninsula near present-day Soria, continued for years and revealed weaknesses in the discipline and strategy of the Roman military.2 The willingness of pre-Romanized inhabitants of the small settlement of Numantia to commit suicide rather than submit to the Roman Army is a gripping tale that continues to move readers today.3 Reassessing depictions of confrontations and other retellings of the conquest of Ancient Iberia by the Romans reveal approaches to historiography, multiculturalism, and 1 In the late sixteenth century, reports arriving from the American continent and Castilian colonies were increasingly mixed about Imperial successes abroad. -

The Celts in Iberia: an Overview

The Celts in Iberia: An Overview Alberto J. Lorrio, Universidad de Alicante Gonzalo Ruiz Zapatero, Universidad Complutense de Madrid Abstract A general overview of the study of the Celts in the Iberian Peninsula is offered from a critical perspective. First, we present a brief history of research and the state of research on ancient written sources, linguistics, epigraphy and archaeological data. Second, we present a different hypothesis for the "Celtic" genesis in Iberia by applying a multidisciplinary approach to the topic. Finally, on the one hand an analysis of the main archaeological groups (Celtiberian, Vetton, Vaccean, the Castro Culture of the northwest, Asturian-Cantabrian and Celtic of the southwest) is presented, while on the other hand we propose a new vision of the Celts in Iberia, rethinking the meaning of "Celtic" from a European perspective. Keywords Celts, Iberian Peninsula, Iron Age, Celtiberians, Indo-European. 1. Introduction Textbooks on European prehistory published during the last seventy-five years confirm that ever since the first theories were formulated at the beginning of the nineteenth century, the Celts have played a crucial role in studies of European protohistory. The Celts have even been accused of taking over Europe during the Iron Age, through the cultures of Hallstatt and La Tène. Any conclusions drawn by European historiography about the Celts have been based on the image conjured up by Classical sources and the archaeological and cultural evidence collected at La Tène. It was only during the mid 1980s that scholars began to debate this issue and started to break away from the conventional established image of the Celts (Collis 2003; Ruiz Zapatero 1993, 2001). -

Diane Bani-Esraili

Cervantes’ El Cerco de Numancia: An Argument Based on Blood Based Determination of Hispanidad Diane Bani-Esraili 64 I. Introduction and Statement of Purpose de Numancia (1582) is marked by mass brutality, bloodshed, and death. Cervantes portrays bodily suffering throughout the work—from to the scene of a father killing his helplessly compliant wife and every last Numantine enemy already dead and the city engulfed in “un rojo lago”1 of blood. Blood pervades Numancia; indeed, it is the principal trope. In This paper will discuss those different meanings and associations and, thereby, establish the centrality of the role of blood in early modern Spanish society. Based on that foundation, this paper will go on to explain how Cervantes uses the legendary point of origin of the Spanish nation— the siege of Numantia during the Roman conquest of the Iberian Peninsula in the second century BCE—to reevaluate the relationship between blood and hispanidad. Through his play Cervantes discredits the prevalent notion of his time that limpieza de sangre (purity of blood) is the determinant of hispanidad. This paper will demonstrate that while he discredits limpieza de sangre as the determinant of hispanidad, he still Holy Blood or sacramental embodiment of the Eucharist that is the true, and only true, link Spaniards can claim to their Numantine it is Holy Blood—voluntary, Christian action—rather than purity of blood—predetermined accident of birth—that determines hispanidad. 65 II. Historical Context and Discourses of Blood It is important to understand the social and religious historical context by which Cervantes was influenced and from which Numancia and its anti-mainstream argument about blood and hispanidad emerge.2 role in both social and religious arenas (which, by nature, often overlap) and multiple and simultaneous discourses of blood existed. -

Celtiberians

SBORNÍK PRACÍ FILOZOFICKÉ FAKULTY BRNĚNSKÉ UNIVERZITY STUDIA MINORA FACULTATIS PHILOSOPHICAE UNIVERSITATIS BRUNENSIS N 12, 2007 Václav BLAžEK CELTIBERIAN 1. Historical witness 2. Origin of the ethnonym 3. Most important inscriptions 4. Grammatical sketch 4.1. Historical phonology 4.2. Historical morphology 4.2.1. Nominal declension in context of other old Celtic languages 4.2.2. Pronouns 4.2.3. Numerals 4.2.4. Verbs 4.2.5. Prepositions, prefixes & preverbs 4.2.6. Conjunctions & negation. 5. Basic bibliography. 1. Historical witness From the antique authors the most detailed information about Celtiberia and its inhabitants was mediated by Strabo [III, 4; translation Horace L. Jones]: (§12) “Crossing over the Idubeda Mountain, you are at once in Celtiberia, a large and uneven country. The greater part of it in fact is rugged and river-washed; for it is through these regions that the Anas flows, and also the Tagus, and the several rivers next to them, which, rising in Celtiberia, flow down to the western sea. Among these are Durius, which flows part Numantia and Serguntia, and the Bae- tis, which, rising in the Orospeda, flows through Oretania into Baetica. Now, in the first place, the parts to the north of the Celtiberians are the home of the Ve- ronians, neighbours of the Cantabrian Coniscans, and they too have their origin in the Celtic expedition; they have a city, Varia, situated at the crossing of the Iberus; and their territory also runs contiguous to that of the Barduetans, whom the men of today call Bardulians. Secondly, the parts on the western side are the home of some of the Asturians, Callaicans, and Vaccaeans,and also of the Vettonians and Carpetanians.