1 Doc. SC.42.10.4 CONVENTION on INTERNATIONAL TRADE

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

IITM Journal of Business Studies (JBS) 2020

Volume 7 Issue 1 January - December 2020 ISSN 2393-9451 Contents 1. An Appraisal Of Prominent Green Marketing 3-13 Communication Themes As Part Of Green marketing Strategies 2. A Study On Impact Of Nursing Staff Turnover On Hospital 14-27 Efficiency At A Trust-Based Hospital, Vadodara 3. A Study On The Importance Of Black Swans And Var 28-39 4. An HR Manager Confronting Challenge Of Change 40-52 (Case Study On Employee Attendance Management) 5. Job Satisfaction Among Employees With Chronic Illness And 53-65 Resultant Work Disability: Effect Of Employer Related Variables 6. Blockchain Solution For Third Party Administrator Process 66-70 In Health Insurance Medical Claims 7. Cluster Development Of MSME Sector In India: 71-76 An Inter-State Analysis 8. Shareholders’ Value Creation In The Sun Pharma-Ranbaxy 77-86 Merger: An Event Study 9. Efficiency Of Indian Stock Market- A Study Of Existence Of 87-98 Arbitrage Gains Through Put Call Parity 10. Electronic Word Of Mouth And Eloquence: 99-104 An Analysis Of Reviews In Hospitality Sector IITM Journal of Business Studies 1 Volume 7 Issue 1 January - December 2020 ISSN 2393-9451 11. Employee Participation In Decision Making And 105-117 Employee Job Satisfaction: The Moderating Role Of Emotional Intelligence 12. Evolving A Pshycometric Instrument To Measure 118-126 Work Life Balance 13. Financial Literacy Leads To Development: 127-140 Mediating Role Of Financial Inclusion, An Empirical Study 14. Flu-Conomics And Its Impact Globally With Special 141-148 Study How To Overstrip From This Grim For India 15. GDS Xerox: Addressing The Right Segment 149-154 16. -

Directory of the European Commission

Directory of the European Commission 16 JUNE 1994 Directory of the European Commission 16 JUNE 1994 Cataloguing data can be found at the end of this publication The information in the Directory was correct at the time of going to press but is liable to change Luxembourg: Office for Official Publications of the European Communities, 1994 ISBN 92-826-8491-1 Reproduction is authorized, except for commercial purposes, provided the source is acknowledged. Printed in Belgium Contents 5 The Commission Special responsibilities of the Members of the Commission 7 11 Secretarial-General of the Commission 17 — Forward Studies Unit 19 Inspectorate-General 21 Legal Service 23 Spokesman's Service 25 Joint Interpreting and Conference Service 27 Statistical Office 31 Translation Service 37 Informatics Directorate 39 Security Office Directorates-General 41 DG I — External Economic Relations 49 DG IA — External Political Relations 53 TFE — Enlargement Task Force 55 DG H — Economic and Financial Affairs 59 DG III — Industry 65 DG IV — Competition 69 DG V — Employment. Industrial Relations and Social Affairs 73 DG VI — Agriculture 79 — Veterinary and Phytosanitary Office 81 DG VII — Transport 83 DG VIII — Development 3 DG IX — Personnel and Administration 89 DG X — Audiovisual .Media, Information, Communication and Culture 93 DG XI — Environment, Nuclear Safety and Civil Protection 97 DG XII — Science, Research and Development 99 — Joint Research Centre 105 DG XIII — Telecommunications, Information Market and Exploitation of Research 111 DGXIV —Fisheries 117 DG XV —Internal Market and Financial Services 121 DG XVI — Regional Policies 125 DG XVII — Energy 129 DG XVIII—Credit and Investments 133 DGXIX —Budgets 135 DG XX — Financial Control 137 DG XXI — Customs and Indirect Taxation 141 DG XXIII— Enterprise Policy, Distributive Trades, Tourism and Cooperatives 143 Consumer Policy Service 145 Task Force for Human Resources. -

In Search of the Amazon: Brazil, the United States, and the Nature of A

IN SEARCH OF THE AMAZON AMERICAN ENCOUNTERS/GLOBAL INTERACTIONS A series edited by Gilbert M. Joseph and Emily S. Rosenberg This series aims to stimulate critical perspectives and fresh interpretive frameworks for scholarship on the history of the imposing global pres- ence of the United States. Its primary concerns include the deployment and contestation of power, the construction and deconstruction of cul- tural and political borders, the fluid meanings of intercultural encoun- ters, and the complex interplay between the global and the local. American Encounters seeks to strengthen dialogue and collaboration between histo- rians of U.S. international relations and area studies specialists. The series encourages scholarship based on multiarchival historical research. At the same time, it supports a recognition of the represen- tational character of all stories about the past and promotes critical in- quiry into issues of subjectivity and narrative. In the process, American Encounters strives to understand the context in which meanings related to nations, cultures, and political economy are continually produced, chal- lenged, and reshaped. IN SEARCH OF THE AMAzon BRAZIL, THE UNITED STATES, AND THE NATURE OF A REGION SETH GARFIELD Duke University Press Durham and London 2013 © 2013 Duke University Press All rights reserved Printed in the United States of America on acid- free paper ♾ Designed by Heather Hensley Typeset in Scala by Tseng Information Systems, Inc. Library of Congress Cataloging-in - Publication Data Garfield, Seth. In search of the Amazon : Brazil, the United States, and the nature of a region / Seth Garfield. pages cm—(American encounters/global interactions) Includes bibliographical references and index. -

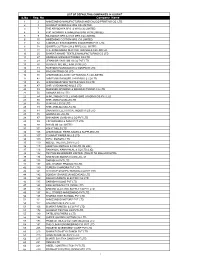

S.No Reg. No Company Name 1 2 AHMEDABAD MANUFACTURING and CALICO PRINTING CO

LIST OF DEFAULTING COMPANIES IN GUJRAT S.No Reg. No Company_Name 1 2 AHMEDABAD MANUFACTURING AND CALICO PRINTING CO. LTD. 2 3 GUJARAT GINNING & MFG CO.LIMITED. 3 7 THE ARYODAYA SPG & WVG.CO.LIMITED. 4 8 40817HCHOWK & AHMEDABAD MFG CO.LIMITED. 5 9 RAJNAGAR SPG & WVG MFG.CO.LIMITED. 6 10 HMEDABAD COTTON MFG. CO.LIMITED. 7 12 12DISPLAY STATUSSTEEL INDUSTRIES PVT. LTD. 8 18 ISHWER COTTON G.N.& PRES.CO.LIMITED. 9 22 THE AHMEDABAD NEW COTTON MILLS CO.LIMITED. 10 25 BHARAT KHAND TEXTILE MANUFACTURING CO LTD 11 27 HIMABHAI MANUFACTURING CO LTD 12 29 JEHANGIR VAKIL MILLS CO PVT LTD 13 30 GUJARAT OIL MILL & MFG CO LTD 14 31 RUSTOMJI MANGALDAS & COMPANY LTD 15 34 FINE KNITTING CO LTD 16 40 AHMEDABAD LAXMI COTTON MILLS CO.LIMITED. 17 42 AHMEDABAD KAISER-I-HIND MILLS CO LTD 18 45 AHMEDABAD NEW TEXTILE MILS CO LTD 19 47 SHRI VIVEKANAND MILLS LTD 20 49 MARSDEN SPINNING & MANUFACTURING CO LTD 21 50 ASHOKA MILLS LTD. 22 54 AHMEDABAD CYCLE & MOTORS TRADING CO PVT LTD 23 68 SHRI AMRUTA MILLS LTD 24 78 VIJAY MILLS CO LTD 25 79 SHRI ARBUDA MILLS LTD. 26 81 DHARWAR ELECTRICAL INDUSTRIES LTD 27 85 ANANTA MILLS LTD 28 87 BHIKABHAI JIVABHAI & CO PVT LTD 29 89 J R VAKHARIA & SONS PVT LTD 30 99 BIHARI MILLS LIMITED 31 101 ROHIT MILLS LTD 32 106 AHMEDABAD FIBRE-SALES & SUPPLIES LTD 33 107 GUJARAT PAPER MILLS LTD 34 109 IDEAL MOTORS LTD 35 110 MODEL THEATRES PVT LTD 36 115 HIMATLAL MOTILAL & CO LTD.(IN LIQ.) 37 116 RAMANLAL KANAIYALAL & CO LTD.(LIQ). -

Albuquerque Daily Citizen, 08-06-1900 Hughes & Mccreight

University of New Mexico UNM Digital Repository Albuquerque Citizen, 1891-1906 New Mexico Historical Newspapers 8-6-1900 Albuquerque Daily Citizen, 08-06-1900 Hughes & McCreight Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalrepository.unm.edu/abq_citizen_news Recommended Citation Hughes & McCreight. "Albuquerque Daily Citizen, 08-06-1900." (1900). https://digitalrepository.unm.edu/abq_citizen_news/1567 This Newspaper is brought to you for free and open access by the New Mexico Historical Newspapers at UNM Digital Repository. It has been accepted for inclusion in Albuquerque Citizen, 1891-1906 by an authorized administrator of UNM Digital Repository. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Jb Printing ta all Mi BtunotM teat n 4 iua j hranchn dons u t I mule a J ahs aVasaaSasI f be al THE CJTUEN lob f THi crnziN 4 Room. The Albuquerque Daily Citizen. Lu VOLUME 14. ALBUQUERQUE, NEW MEXICO, MONDAY AFTERNOON, AUGUST 6, 1900. NUMBER ?42. York. From that Tint lie apeak only feet Into ths skle of ths mountain BIG In New York atate. He safd ha waa ae-- above Kelly for ths purpose of reach- ! BATTLE! cned to cover every county In Now L0ST1UFE! ing an apex vein of ore whtch haa been COEBELMljRDER York. prospected from ths summit of thi ova MOST mountain to a depth of nearly too feet. KaaaaaClty Market. This vein ta four feet wids tha sur- -- Re- at 1 1 1 1 1 1 Kansas City, Auf. Cattle face and increases both In width and at,a:;t7oV i L. ceipts, 11,000; weak to 10 cent lower, L u IJ i?jzxzr In richness of ore downward. -

FINAL DISTRIBUTION.Xlsx

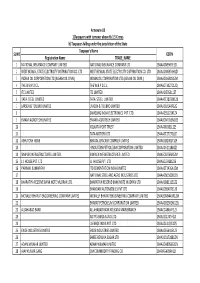

Annexure-1B 1)Taxpayers with turnover above Rs 1.5 Crores b) Taxpayers falling under the jurisdiction of the State Taxpayer's Name SL NO GSTIN Registration Name TRADE_NAME 1 NATIONAL INSURANCE COMPANY LIMITED NATIONAL INSURANCE COMPANY LTD 19AAACN9967E1Z0 2 WEST BENGAL STATE ELECTRICITY DISTRIBUTION CO. LTD WEST BENGAL STATE ELECTRICITY DISTRIBUTION CO. LTD 19AAACW6953H1ZX 3 INDIAN OIL CORPORATION LTD.(ASSAM OIL DIVN.) INDIAN OIL CORPORATION LTD.(ASSAM OIL DIVN.) 19AAACI1681G1ZM 4 THE W.B.P.D.C.L. THE W.B.P.D.C.L. 19AABCT3027C1ZQ 5 ITC LIMITED ITC LIMITED 19AAACI5950L1Z7 6 TATA STEEL LIMITED TATA STEEL LIMITED 19AAACT2803M1Z8 7 LARSEN & TOUBRO LIMITED LARSEN & TOUBRO LIMITED 19AAACL0140P1ZG 8 SAMSUNG INDIA ELECTRONICS PVT. LTD. 19AAACS5123K1ZA 9 EMAMI AGROTECH LIMITED EMAMI AGROTECH LIMITED 19AABCN7953M1ZS 10 KOLKATA PORT TRUST 19AAAJK0361L1Z3 11 TATA MOTORS LTD 19AAACT2727Q1ZT 12 ASHUTOSH BOSE BENGAL CRACKER COMPLEX LIMITED 19AAGCB2001F1Z9 13 HINDUSTAN PETROLEUM CORPORATION LIMITED. 19AAACH1118B1Z9 14 SIMPLEX INFRASTRUCTURES LIMITED. SIMPLEX INFRASTRUCTURES LIMITED. 19AAECS0765R1ZM 15 J.J. HOUSE PVT. LTD J.J. HOUSE PVT. LTD 19AABCJ5928J2Z6 16 PARIMAL KUMAR RAY ITD CEMENTATION INDIA LIMITED 19AAACT1426A1ZW 17 NATIONAL STEEL AND AGRO INDUSTRIES LTD 19AAACN1500B1Z9 18 BHARATIYA RESERVE BANK NOTE MUDRAN LTD. BHARATIYA RESERVE BANK NOTE MUDRAN LTD. 19AAACB8111E1Z2 19 BHANDARI AUTOMOBILES PVT LTD 19AABCB5407E1Z0 20 MCNALLY BHARAT ENGGINEERING COMPANY LIMITED MCNALLY BHARAT ENGGINEERING COMPANY LIMITED 19AABCM9443R1ZM 21 BHARAT PETROLEUM CORPORATION LIMITED 19AAACB2902M1ZQ 22 ALLAHABAD BANK ALLAHABAD BANK KOLKATA MAIN BRANCH 19AACCA8464F1ZJ 23 ADITYA BIRLA NUVO LTD. 19AAACI1747H1ZL 24 LAFARGE INDIA PVT. LTD. 19AAACL4159L1Z5 25 EXIDE INDUSTRIES LIMITED EXIDE INDUSTRIES LIMITED 19AAACE6641E1ZS 26 SHREE RENUKA SUGAR LTD. 19AADCS1728B1ZN 27 ADANI WILMAR LIMITED ADANI WILMAR LIMITED 19AABCA8056G1ZM 28 AJAY KUMAR GARG OM COMMODITY TRADING CO. -

Top 150 Global Licensors Report for the Very First Time, Debuting at No

APRIL 2018 VOLUME 21 NUMBER 2 Plus: The Walt Disney Company Tops Report at $53B 12 Licensors Join the Top 150 GOES OUTSIDE THE LINES Powered by Crayola is much more than a crayon. The iconic brand has strengthened its licensing program to ensure it brings meaningful products for people of all ages to market for years to come. This year, Crayola joins License Global’s Top 150 Global Licensors report for the very first time, debuting at No. 116. WHERE FASHION AND LICENSING MEET The premier resource for licensed fashion, sports, and entertainment accessories. Top 150 Global Licensors GOES OUTSIDE THE LINES Crayola is much more than a crayon. The iconic brand has strengthened its licensing program to ensure it brings meaningful products for people of all ages to market for years to come. This year, Crayola joins License Global’s Top 150 Global Licensors report for the very first time, debuting at No. 116. by PATRICIA DELUCA irst, a word of warning for prospective licensees: Crayola Experience. And with good reason. The Crayola if you wish to do business with Crayola, wear Experience presents the breadth and depth of the comfortable shoes. Initial business won’t be Crayola product world in a way that needs to be seen. Fconducted through a series of email threads or Currently, there are four Experiences in the U.S.– conference calls, instead, all potential partners are asked Minneapolis, Minn.; Orlando, Fla.; Plano, Texas; and Easton, to take a tour of the company’s indoor family attraction, Penn. The latter is where the corporate office is, as well as the nearby Crayola manufacturing facility. -

Making the Case for International Trade Why Exporting Matters in 2019

W Issue Four O : Spring 2019 R L D T R A D E M A WORLD T T E R S | T h e P r o f e s s i o TRADE n a l J o u r n a l f MATTERS r o The Professional Journal from the Institute of Export & m t International Trade h e I n s t i t u t e Making the Case for International Trade o f E x p Why Exporting Matters in 2019 o r t & I n t e Andrew Staines – Why the WTO matters and the UK’s r n a role within it t i o n a Barry Gardiner MP – l Assessing the UK’s future trade policy T r a d e Alexandre Fasel – Multilateralism versus protectionism Stephen Phipson – The importance of trade to UK manufacturing Chris Southworth – Why international trade matters for the UK Tips on Doing Business in: u Argentina u Egypt u Ukraine u Qatar I s s u e F o u r : S p r i n g 2 0 1 9 www.export.org.uk : @ioexport Open to Export is a free online information service from The Institute of Export & International Trade, dedicated to helping small UK businesses get ready to export and expand internationally How can we help? A wealth of free information and A comprehensive webinar Quarterly competitions for the practical advice on our website programme covering all aspects chance to win £3,000 cash and using: of international trade further support Step-by-step guides covering The online Export Action Plan the whole export journey from tool helping businesses create a Sign up today to take your ‘Selecting a market’ to ‘Delivery roadmap to successful new markets next steps in international trade and documentation’ Powered By Register for free on www.opentoexport.com for updates on our content and webinars, and to start your Export Action Plan. -

PREVIEW Claims Handling Law and Practice

KENNEDYS CLAIMS HANDLING LAW AND PRACTICE A Practitioner’s Guide Third edition As your business and the industry around you changes, you need lawyers who innovate and help you think ahead. At Kennedys, we have the experience and foresight to take on your challenges and adapt to your changing needs. We are an award-winning global legal services provider with proven expertise in dispute resolution and advisory services. Throughout our growing network of offices we specialise in defending insurance and liability claims, and providing claims and coverage advice across all lines of business. We provide legal services to a client base that includes domestic and international (re)insurers, Lloyd’s syndicates, central and local government bodies and large self-insured corporate organisations. We take a strategic and commercial approach to helping you defend claims, manage your and your customers’ risk, and save money. Our core principle is to help make our clients more self-sufficient; enabling them to only use a lawyer when they truly need one. This third and expanded edition will once again assist and support our clients in their day jobs. It provides them with our know-how and expertise in a straightforward way that draws on over 100 years of experience, from more than 200 partners, across our business. Claims Handling Law and Practice Claims Handling Law and Practice A Practitioner’s Guide To Fred and Kieron with thanks for your wisdom and guidance. i Claims Handling Law and Practice Material from the Civil Procedure Rules, Ogden tables and legislation is reproduced by permission of, and is subject to, Crown copyright and is licensed for use under the Open Government Licence, which is available at www.nationalarchives.gov.uk/doc/open-government-licence/version/3/ MIB Agreements are reproduced by permission of MIB Group. -

“List of Companies/Llps Registered During the Year 1983”

“List of Companies/LLPs registered during the year 1983” Note: The list include all companies/LLPs registered during this period irrespective of the current status of the company. In case you wish to know the current status of any company please access the master detail of the company at the MCA site http://mca.gov.in Sr. No. CIN/FCRN/LLPIN/FLLPIN Name of the entity Date of Registration 1 U51103TN1983PTC009783 CARS INDIA PRIVATE LIMITED 1/1/1983 2 U24231GJ1983PTC005803 CHEM DEAL DYESTUFF PRIVATE LIMITED 1/1/1983 3 U92111KL1983PTC003662 ANJALI FILMS PRIVATE LIMITED 1/1/1983 4 U28111CT1983PTC002118 AMBER STEEL INDUSTRIES PVT LTD 1/1/1983 5 U24246KA1983PTC005099 KUNTHALARANJANI PERFUMORY WORKS PRIVATE LIMITED 1/1/1983 6 U01119TN1983PTC009784 NACHALUR PLANTATIONS PVT LTD 1/1/1983 7 U32106MH1983PTC029019 FIVE FINGERS ELECTRONICS PVT LTD 1/1/1983 8 U45203OR1983SGC001153 ODISHA BRIDGE & CONSTRUCTION CORPORATION LIMITED 1/1/1983 9 U31102CT1983PTC002117 MAHINDRA FORGING INDUSTRIES PVT.LTD. 1/1/1983 10 U29129TN1983PTC009785 XL PRESSING PRIVATE LIMITED 1/1/1983 11 U63040MH1983PTC029018 TEZTAIR TRAVELS PRIVATE LIMITED 1/1/1983 12 U65993GJ1983PTC005804 DERBY INVESTMENTS PRIVATE LIMITED 1/1/1983 13 U99999MH1983PTC029017 RUKADI METAL CASTINGS PVT LTD 1/1/1983 14 U63040MH1983PTC029020 MUWADA TRAVELS PVT LTD. 1/1/1983 15 U99999MH1983PTC029021 EMTEK ENGINEERS PRIVATE LIMITED 1/1/1983 16 F00910 CGEE ALATHOM, 1/1/1983 17 U67120WB1983PLC035735 COLORADO INVESTMENTS LTD. 1/3/1983 18 L15500WB1983PLC035627 GRANDEUR PRODUCTS LIMITED 1/3/1983 19 L01132WB1983PLC035629 -

Omission Site Hampton Magna

Technical Report – Old Budbrooke Road, Hampton Magna • Breakers • Rollers • Piling to plots • Cutting with abrasive wheels Working Hours 7.15 Construction work and deliveries will take place between certain hours and days of the week, to be agreed with Warwick District Council. No activities requiring 24 hour, Sunday or Bank Holiday working are envisaged. 7.16 If there was a requirement for out-of-hours working, then a Site Hours Variation Request Form will be completed and forwarded to Warwick District Council at least five days before activities are planned to take place. Variation of site hours will only be worked once approval has been given and the form countersigned by the relevant officers at Warwick District Council. Vehicle Routes 7.17 Preliminary discussions with Highways England (HE) have taken place to establish the viability of accessing the site for purposes of the construction phase only from the A46 via a link road to be taken from the existing service station area. Whilst the HE have indicated they would give due regard to any such request early indications would suggest that they would not look favourably on this option and based on experience from other site located alongside the Trunk Road it is considered highly unlikely an acceptable form of access could be agreed. 7.18 As with any other development site in Hampton Magna construction traffic will therefore be required to access the site from the local road network. The following is considered: • Smaller vehicles with limit height have the ability to access from any of the surrounding highway network. -

12–23–04 Vol. 69 No. 246 Thursday Dec. 23, 2004 Pages 76835–77138

12–23–04 Thursday Vol. 69 No. 246 Dec. 23, 2004 Pages 76835–77138 VerDate jul 14 2003 19:47 Dec 22, 2004 Jkt 205001 PO 00000 Frm 00001 Fmt 4710 Sfmt 4710 E:\FR\FM\23DEWS.LOC 23DEWS i II Federal Register / Vol. 69, No. 246 / Thursday, December 23, 2004 The FEDERAL REGISTER (ISSN 0097–6326) is published daily, SUBSCRIPTIONS AND COPIES Monday through Friday, except official holidays, by the Office PUBLIC of the Federal Register, National Archives and Records Administration, Washington, DC 20408, under the Federal Register Subscriptions: Act (44 U.S.C. Ch. 15) and the regulations of the Administrative Paper or fiche 202–512–1800 Committee of the Federal Register (1 CFR Ch. I). The Assistance with public subscriptions 202–512–1806 Superintendent of Documents, U.S. Government Printing Office, Washington, DC 20402 is the exclusive distributor of the official General online information 202–512–1530; 1–888–293–6498 edition. Periodicals postage is paid at Washington, DC. Single copies/back copies: The FEDERAL REGISTER provides a uniform system for making Paper or fiche 202–512–1800 available to the public regulations and legal notices issued by Assistance with public single copies 1–866–512–1800 Federal agencies. These include Presidential proclamations and (Toll-Free) Executive Orders, Federal agency documents having general FEDERAL AGENCIES applicability and legal effect, documents required to be published Subscriptions: by act of Congress, and other Federal agency documents of public interest. Paper or fiche 202–741–6005 Documents are on file for public inspection in the Office of the Assistance with Federal agency subscriptions 202–741–6005 Federal Register the day before they are published, unless the issuing agency requests earlier filing.