Elizabeth and Ffrancis Trentham of Rocester Abbey by Jeremy Crick

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

PC 180522 08 Delegated Report.Pdf

Item No 6 REPORT OF THE SAL KHAN CPFA, MSc, HEAD OF SERVICE ON APPLICATIONS DETERMINED UNDER DELEGATED AUTHORITY BETWEEN 16/04/2018 AND 08/05/2018 APPROVED/APPROVED WITH CONDITIONS 83 Alan Harvey P/2018/00173 Proposed Barn Conversion Prior approval for the conversion of an agricultural PAC Poplar Farm building to form a dwelling Q Poplar Farm Road Bromley Hurst Abbots Bromley Staffordshire P/2018/00177 Lavender Croft Conversion and alterations of former workshop to PA Old Uttoxeter Road form a dwelling, external alterations to include Crakemarsh recladding, increase in roof pitch, installation of ST14 5AR solar panels and septic tank and formation of separate driveway (Revised scheme) P/2018/00199 94 Pennycroft Road Formation of a new vehicular access including HO Uttoxeter dropped kerb and hardstanding ST14 7ET P/2018/00236 The Old Stables Erection of a single storey rear extension HO Wood Lane Uttoxeter Staffordshire ST14 8JR P/2018/00300 Rose Villa Fell 2 Conifer trees, 1 Elder tree, 1 Lilac tree, 1 TN Lichfield Road Schumacher tree and 3 Hazel trees, trim back 1 Abbots Bromley Cotoneaster tree and 1 Yew tree, remove lower Staffordshire branches from 1 Goat Willow tree and 2 Conifer WS15 3DL trees, coppice 1 Rhododendron tree, pollard 1 Elder tree, removal of rogue branches from canopy of 1 Cherry tree and reduce the height of 4 Conifer trees to 6 metres P/2018/00334 Ashbourne Road Discharge of condition no 13 of planning DOC Rocester permission P/2014/00548 relating to the outline application for the erection of up to 53 dwellings -

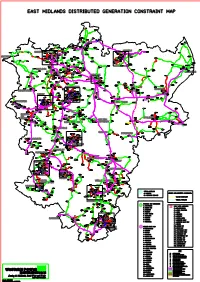

East Midlands Constraint Map-Default

EAST MIDLANDS DISTRIBUTED GENERATION CONSTRAINT MAP MISSON MISTERTON DANESHILL GENERATION NORTH WHEATLEY RETFOR ROAD SOLAR WEST GEN LOW FARM AD E BURTON MOAT HV FARM SOLAR DB TRUSTHORPE FARM TILN SOLAR GENERATION BAMBERS HALLCROFT FARM WIND RD GEN HVB HALFWAY RETFORD WORKSOP 1 HOLME CARR WEST WALKERS 33/11KV 33/11KV 29 ORDSALL RD WOOD SOLAR WESTHORPE FARM WEST END WORKSOPHVA FARM SOLAR KILTON RD CHECKERHOUSE GEN ECKINGTON LITTLE WOODBECK DB MORTON WRAGBY F16 F17 MANTON SOLAR FARM THE BRECK LINCOLN SOLAR FARM HATTON GAS CLOWNE CRAGGS SOUTH COMPRESSOR STAVELEY LANE CARLTON BUXTON EYAM CHESTERFIELD ALFORD WORKS WHITWELL NORTH SHEEPBRIDGE LEVERTON GREETWELL STAVELEY BATTERY SW STN 26ERIN STORAGE FISKERTON SOLAR ROAD BEVERCOTES ANDERSON FARM OXCROFT LANE 33KV CY SOLAR 23 LINCOLN SHEFFIELD ARKWRIGHT FARM 2 ROAD SOLAR CHAPEL ST ROBIN HOOD HX LINCOLN LEONARDS F20 WELBECK AX MAIN FISKERTON BUXTON SOLAR FARM RUSTON & LINCOLN LINCOLN BOLSOVER HORNSBY LOCAL MAIN NO4 QUEENS PARK 24 MOOR QUARY THORESBY TUXFORD 33/6.6KV LINCOLN BOLSOVER NO2 HORNCASTLE SOLAR WELBECK SOLAR FARM S/STN GOITSIDE ROBERT HYDE LODGE COLLERY BEEVOR SOLAR GEN STREET LINCOLN FARM MAIN NO1 SOLAR BUDBY DODDINGTON FLAGG CHESTERFIELD WALTON PARK WARSOP ROOKERY HINDLOW BAKEWELL COBB FARM LANE LINCOLN F15 SOLAR FARM EFW WINGERWORTH PAVING GRASSMOOR THORESBY ACREAGE WAY INGOLDMELLS SHIREBROOK LANE PC OLLERTON NORTH HYKEHAM BRANSTON SOUTH CS 16 SOLAR FARM SPILSBY MIDDLEMARSH WADDINGTON LITTLEWOOD SWINDERBY 33/11 KV BIWATER FARM PV CT CROFT END CLIPSTONE CARLTON ON SOLAR FARM TRENT WARTH -

To Access Forms and Drawings Associated with the Applications

Printed On 24/08/2020 Weekly List ESBC www.eaststaffsbc.gov.uk Sal Khan CPFA, MSc Head of Service LIST No: 34/2020 PLANNING APPLICATIONS REGISTERED DURING THE PERIOD 17/08/2020 TO 21/08/2020 To access forms and drawings associated with the applications below, please use the following link :- http://www.eaststaffsbc.gov.uk/Northgate/PlanningExplorer/ApplicationSearch.aspx and enter the full reference number. Alternatively you are able to view the applications at:- Customer Services Centre, Market Place, Burton upon Trent or the Customer Services Centre, Uttoxeter Library, Red Gables, High Street, Uttoxeter. REFERENCE Grid Ref: 409,604.00 : 322,105.00 P/2020/00844 Parish(s): Abbots Bromley Prior Approval - Class Q (Agricultural to Dwellin Ward(s): Bagots Prior Approval for the conversion of agricultural building to form dwelling. Proposed barn conversion For Mr Elsout and Ms Hall Ashbrook Farm c/o JMI Planning Orange Lane 62 Carter Street Bromley Hurst Uttoxeter Abbots Bromley ST14 8EU Staffordshire WS15 3AX REFERENCE Grid Ref: 425,208.00 : 323,700.00 P/2020/00679 Parish(s): Burton Detailed Planning Application Ward(s): Burton Conversion and alterations of two detached buildings to provide 165 apartments and studios Nos 1 & 2 The Maltings For Maltings Developments Limited Wetmore Road c/o Thorne Architecture Limited Burton Upon Trent The Creative Industries Centre Staffordshire Wolverhampton Science Park DE14 1SF Glaisher Drive WOLVERHAMPTON WV10 9TG Page 1 of 10 Printed On 24/08/2020 Weekly List ESBC LIST No: 34/2020 REFERENCE Grid Ref: -

Luxury Living, Exceptional Care & Unrivalled Views

NURSING|RESIDENTIAL|DEMENTIA Luxury Living, Exceptional Care & Unrivalled Views Award Winning Dementia Care and Nursing Home See all the reviews for yourself at Please telephone: 01889 591006 Email: [email protected] Website: www.barrowhillhall.co.uk 1. Welcome to Barrowhill Hall Geoff Aris (award winners) Fine Dining Senior Carer Lauren Barrowhill Hall is an award-winning specialist dementia care and nursing home standing on the crest of a hill on “ the Derbyshire/Staffordshire border in a beautiful and tranquil setting with panoramic views of the surrounding countryside. We offer the highest quality residential and nursing care in a luxurious, homely and safe environment. Barrowhill Hall consists of two independent care centres being Barrowhill Hall and Churnet Lodge. Churnet Lodge Quiet lounge and Smart TV’s Fountain Spa Luxury Décor focuses on providing a socially supportive environment for those living with the early stages of Dementia. Care plans are carefully compiled, updated and are overseen by our management team. Whilst Barrowhill Hall offers care and support for people who have more complex needs requiring the meticulous formulation, implementation and evaluation of bespoke, person centred care plans by our dedicated and professional nursing team. Both Barrowhill and Churnet Lodge have been specially designed in accordance with the innovative Stirling Academy guidance along with our own research into how to enhance the living environment for people living with memory loss. We have a mixture of larger and quieter lounges, film rooms, a library, spa and hairdressers. The outdoor space is extensive and has far reaching views of the local countryside and the formal gardens of the JCB world headquarters. -

Please Ensure Student Is at the Bus Stop 5 Minutes Before Pick up Time

Route 1: Leek/Cheadle to The JCB Academy Coach operator: Stanton’s of Stoke Please ensure student is at the bus stop 5 minutes before pick up time. Students are not permitted to change from allocated transport routes without The JCB Academy approval. ROUTE 1 TIMES Mon, Tue, Wed, AM Thurs & Fri Endon, end of Park Lane 06:55 16:51 Leek, Broad Street, Near Halfords 07:08 16:41 Leek - Prince Street, Buxton Road 07:11 16:39 Leek, Ashbourne Rd, Moorlands Hospital Bus Stop 07:14 16:37 Bottomhouse Crossroads 07:22 16:27 George Pub, Waterhouses 07:25 16:24 The Cross Pub 07:25 16:24 Blakeley Lane, at Jnct A52 07:35 16:17 Froghall Railway Station 07:41 16:12 Kingsley, end of Holt Lane 16:10 Kingsley Holt, Blacksmith Arms P/H 07:44 16:08 Cheadle, opp Premier Shop 07:47 16:06 Cheadle, Leek Rd, Council Offices Bus Stop 07:50 16:05 Cheadle, Ashbourne Rd, just past Leisure Centre 07:54 16:00 Threapwood Bus Shelter 07:55 15:55 Alton, Tythe Barn Bus Stop 08:05 15:52 The JCB Academy 08:10 15:45 Route 2: Endon/Hanley/Blythe Bridge to The JCB Academy Coach operator: Stanton’s of Stoke Please ensure student is at the bus stop 5 minutes before pick up time. Students are not permitted to change from allocated transport routes without The JCB Academy approval. ROUTE 2 TIMES Mon, Tue, Wed, AM Thurs & Fri Endon High School 07:07 16:51 Stockton Brook - Nr to Holly Bush/Opp Stockton 07:10 16:41 Brook Post Office (pm) Baddeley Green, A53, Trentfields Rd 07:13 16:39 Sneyd Green, Sneyd Arms Bus Stop 07:17 16:37 Hanley Stafford Street – Opp Wilkinson 07:25 16:27 Hanley, -

Road Traffic Regulation Act 1984 (As Amended) Road Traffic (Temporary Restrictions) Act 1991

STAFFORDSHIRE COUNTY COUNCIL ROAD TRAFFIC REGULATION ACT 1984 (AS AMENDED) ROAD TRAFFIC (TEMPORARY RESTRICTIONS) ACT 1991 TEMPORARY TRAFFIC REGULATION NOTICE Rocester Bypass, New Road and Old Denstone Road Rocester NOTICE IS HEREBY GIVEN that Staffordshire County Council being the highway authority responsible for the repair and maintenance of Rocester Bypass, New Road and Old Denstone Road in Rocester are satisfied that it is necessary to implement total closures of that length of Rocester Bypass (B5030) at the roundabout junction with B5031, New Road (B5031) for the full extent and Old Denstone Road near the roundabout entrance to JCB for a period of 4 days but no more than 5 days from 14th June 2021 because of the likelihood of danger to the public during highway repair works being undertaken by Amey on behalf of Staffordshire County Council. Access will be available for pedestrians and for vehicles being used in connection with the works (and for emergency services vehicles or for vehicles requiring access to premises on the length of road which is closed). An alternative route for traffic is available via New Road, Main Road, Elm View, Denstone Lane, Alton Road, Tythe Barn, Gallows Green, Greatgate Lane, Cheadle Road, Ashbourne Road, Tape Street, Tean Road, High Street, Uttoxeter Road, A50 J A522 Join E, A50 From Ashbourne Road Roundabout B5030 To East Staffordshire Borough Council Boundary, A50 From J A522 To J B5030 Roundabout E, A50 J B5030 Roundabout, A518 Ashbourne Road, Woodseat Level, Rocester Bypass and vice versa. https://one.network/?tm=122413281 IT IS ANTICIPATED THAT THE CLOSURE WILL BE IN PLACE BETWEEN 18:00hrs on 14th June 2021 AND 06:00hrs on 17th June 2021. -

Elizabeth and Ffrancis Trentham of Rocester Abbey De Vere Society Newsletter

November 2006 Elizabeth and ffrancis Trentham of Rocester Abbey De Vere Society Newsletter Elizabeth and ffrancis Trentham of Rocester Abbey by Jeremy Crick Part I of a short account of the family history of Edward de Vere Earl of Oxford’s second wife and the strategic importance of the Trentham archive in the search for Oxford’s literary fragments. Accompanied by the Trentham family tree incorporating the de Veres and the Sneyds. Introduction Whether it was Oxford’s son-in-law, Philip When I began my study of the Trentham family, Herbert, Earl of Montgomery, and his brother about two years ago, I had one principal thought in William Herbert, Earl of Pembroke - the mind: if any of Edward de Vere’s literary papers - ‘incomparable brethren’ - who were given access to whether notebooks, original drafts or even literary Oxford’s papers (and which may later have been correspondence - have survived undiscovered till consumed by fire in the library at Wilton), or the present, it must be possible to find them. whether it was another son-in-law, William Stanley, Being a passionate Oxfordian these past Earl of Derby, who began the process of preserving twenty-odd years, I’m as fascinated as all Oxford’s life’s work for posterity, we may never Oxfordians are by the remarkable scholarship that know. has illuminated the ‘Shakespearean’ canon with It is very unlikely, however, that Elizabeth concordances from Oxford’s life, alongside the Trentham divested herself of all of Oxford’s literary broader question of whether the Stratford or the papers for the preparation of the First Folio - to the Oxford biography delivers the better candidate. -

P 2014 00548 Design and Access Statement.Pdf

DESIGN AND ACCESS STATEMENT LAND TO THE EAST OF ASHBOURNE ROAD, ROCESTER ON BEHALF OF BAMFORD PROPERTIES LTD Ref: 2963 DRAFT 1. Introduction 1.1 This Design and Access Statement accompanies the outline planning application made by Bamford Properties Ltd for residential development in Rocester on land to the East of Ashbourne Road. Key 1.2 It is an outline application for up to 53 dwellings along with associated open space and highways works Application Boundary with all matters reserved, save for access. The indicative layout which is submitted in support of this Key application includes: ASHBOURNE ROAD ProposedViewpoint school site • Up to 53 residential properties with associated parking and gardens; • A children’s play area; • Open green space; • Amenity area; • Landscaped areas around the Site boundaries; • Vehicular and pedestrian access from Ashbourne Road; and B5830 • A connection to the footpath network (Rocester 5). 1 This document should be read in conjunction with the accompanying scheme drawings and reports 3 including: • Transport Statement; • Landscape and Visual Appraisal; 2 • Phase 1 Ecology Survey & Great Crested Newt Scoping Survey; NORTHFIELD AVE • Tree Survey; • Flood Risk Assessment; • Heritage Assessment; Site Plan • Planning Statement. 1.3 Design and Access Statements are required by the Planning and Compulsory Purchase Act 2004. The purpose of this document is to: • Provide information concerning the design evolution of the development; • Outline the broad design principles that have led to the form and type of development proposed; • Set the application site in context with its surroundings. Viewpoint 2. View North West across the boundary hedgerow that separates the Ashbourne road Viewpoint 1.Ashbourne Road which bounds the application site to the east. -

Persons Index

Architectural History Vol. 1-46 INDEX OF PERSONS Note: A list of architects and others known to have used Coade stone is included in 28 91-2n.2. Membership of this list is indicated below by [c] following the name and profession. A list of architects working in Leeds between 1800 & 1850 is included in 38 188; these architects are marked by [L]. A table of architects attending meetings in 1834 to establish the Institute of British Architects appears on 39 79: these architects are marked by [I]. A list of honorary & corresponding members of the IBA is given on 39 100-01; these members are marked by [H]. A list of published country-house inventories between 1488 & 1644 is given in 41 24-8; owners, testators &c are marked below with [inv] and are listed separately in the Index of Topics. A Aalto, Alvar (architect), 39 189, 192; Turku, Turun Sanomat, 39 126 Abadie, Paul (architect & vandal), 46 195, 224n.64; Angoulême, cath. (rest.), 46 223nn.61-2, Hôtel de Ville, 46 223n.61-2, St Pierre (rest.), 46 224n.63; Cahors cath (rest.), 46 224n.63; Périgueux, St Front (rest.), 46 192, 198, 224n.64 Abbey, Edwin (painter), 34 208 Abbott, John I (stuccoist), 41 49 Abbott, John II (stuccoist): ‘The Sources of John Abbott’s Pattern Book’ (Bath), 41 49-66* Abdallah, Emir of Transjordan, 43 289 Abell, Thornton (architect), 33 173 Abercorn, 8th Earl of (of Duddingston), 29 181; Lady (of Cavendish Sq, London), 37 72 Abercrombie, Sir Patrick (town planner & teacher), 24 104-5, 30 156, 34 209, 46 284, 286-8; professor of town planning, Univ. -

Sites with Planning Permission As at 30.09.2018)

Housing Pipeline (sites with Planning Permission as at 30.09.2018) Not Started = Remaining Cumulative Total Outline Planning Application Decision Capacity Under Full Planning Parish Address Capacity For monitoring Completions (on partially Planning Number. Date* of Site Construction completed sites upto & Permission Year Permission including 30.09.18) 2 Mayfield Hall Hall Lane Middle Mayfield Staffordshire DE6 2JU P/2016/00808 25/10/2016 3 3 0 0 0 3 3 The Rowan Bank Stanton Lane Ellastone Staffordshire DE6 2HD P/2016/00170 05/04/2016 1 1 0 0 0 1 3 Stanton View Farm Bull Gap Lane Stanton Staffordshire DE6 2DF P/2018/00538 13/07/2018 1 1 0 0 0 1 7 Adjacent Croft House, Stubwood Lane, Denstone, ST14 5HU PA/27443/005 18/07/2006 1 1 0 0 0 1 7 Land adjoining Mount Pleasant College Road Denstone Staffordshire ST14 5HR P/2014/01191 22/10/2014 2 2 0 0 0 2 7 Proposed Conversion Doveleys Rocester Staffordshire P/2015/01623 05/01/2016 1 1 0 0 0 0 7 Dale Gap Farm Barrowhill Rocester Staffordshire ST14 5BX P/2016/00301 06/07/2016 2 2 0 0 0 2 7 Brown Egg Barn Folly Farm Alton Road Denstone Staffordshire P/2016/00902 24/08/2016 1 1 0 0 0 0 7 Alvaston and Fairfields College Road Denstone ST14 5HR P/2017/00050 10/08/2017 2 0 2 0 2 0 7 Land Adjacent to Ford Croft House (Site 1) Upper Croft Oak Road Denstone ST14 5HT P/2017/00571 17/08/2017 5 0 5 0 5 0 7 Land Adjacent to Ford Croft House (Site 2) Upper Croft Oak Road Denstone ST14 5HT P/2017/01180 08/12/2017 2 0 2 0 2 0 7 adj Cherry Tree Cottage Hollington Road Rocester ST14 5HY P/2018/00585 09/07/2018 1 -

FOREVER: KEELE for Keele People Past and Present Issue 8//2013

FOREVER: KEELE For Keele People Past and Present Issue 8//2013 Keele University Contents Who’s Who in the Alumni P1 P6 and Development Team P2 P4 Dawn-Marie Beeston: I graduated from Keele in 2011. I enjoyed my time here so much I didn’t want to leave and last year I was fortunate enough to get a position in the Alumni and Development team. When I’m not at Keele I spend my time with my horses, dogs and family. P8 P10 John Easom: I studied at Keele back in 1980-1981. After twenty years in the Civil Service I moved on to international trade development and then finally got back to Keele in P12 P14 2005. This is the best job of my life. If I could do it wearing skates my joy would be complete. Union Square Lives Fireworks and lasers lit up the Students’ Union Building and the sky above as alumni, students, staff and local residents gathered on 28 November 2012 to witness the official lighting of the ‘Forest of Light’ P18 P32 at the heart of the campus. The 50 slim gleaming stainless steel columns – each Emma Gregory: one representing a Class of Alumni since I started with Keele in 2012. I trained as a 1962 encircle a central plinth inscribed Vet Nurse but being allergic to fur created with a phrase echoing our founder, Lord a bit of a barrier! After four years in the A D LIndsay of Birker: “Search for Truth in Civil Service, it was time for a complete the Company of Friends”. -

Mark Winnington

Philip Atkins County Councillor for Uttoxeter Rural Annual Report 9 May 2017 – 31 March 2018 Introduction I was first elected as County Councillor for the Uttoxeter Rural electoral division in May 1987. My division lies in the north and east of East Staffordshire and includes the wards of Bagots, Abbey, Churnet and Weaver and part of the ward of Crown (Marchington and Draycott – in – the – Clay and covers approximately 21155 with a population of 12,343. Special Responsibilities I am Leader of the County Council Committee Membership and Attendance Record My committee membership and attendance record can be seen below:- Meeting title Possible Actual Apols Absent In attendances attendances Attendance Annual Business 1 1 0 0 0 Rates Consultation Meeting Cabinet 11 7 4 0 0 Children’s 10 5 5 0 0 Improvement Board Corporate Review 1* 0 1* 0 2 Committee County Council 8 8 0 0 0 Local Member Priority 6 3 3 0 0 – East Staffordshire Pensions Committee 6 3 2 1 0 Pensions Panel 4 3 1 0 0 Political Cabinet 7 7 0 0 0 Pre-Cabinet 10 8 2 0 0 Property Informal 4 3 1 0 0 Briefing Property Sub- 4 3 1 0 0 Committee Special Committee re: 1 1 0 0 0 Remuneration Special Committee re: 3 3 0 0 0 Commissioner for Business and Enterprise Special Committee re: 1 1 0 0 0 Strategy, Governance and Change – Wider Leadership Team Structure Special Committee to 2 2 0 0 0 exercise functions under the Officer Employment Rules Stoke on Trent and 1 1 0 0 0 Staffordshire Enterprise Partnership – Executive Group Stoke on Trent and 1 0 1 0 0 Staffordshire Enterprise Partnership – Board Strategic Property 4 3 1 0 0 Board Total 85 62 22 1 0 Count % Possible attendances 85 Actual attendances 62 73% Apologies 22 26% Absent 1 1% In attendance 0 0% Member comments on committees/attendance record My role as Leader means I cannot attend every meeting as I represent Staffordshire elsewhere.