7 X 11.5 Three Lines.P65

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

150 Years of Collecting Impressionist Art: from the Avant-Garde to the Mainstream

150 Years of Collecting Impressionist Art: From the Avant-Garde to the Mainstream CENTER FOR THE HISTORY OF COLLECTING SYMPOSIUM friday & saturday, may 11 & 12, 2018 TO PURCHASE TICKETS, visit frick.org/research/center Both days $50 (Members $35) Single day $30 (Members $25) friday, may 11 3:15 registration 3:30 welcome and opening remarks Ian Wardropper, Director, The Frick Collection Inge Reist, Director, Center for the History of Collecting, Frick Art Reference Library 3:45 keynote address The Private Collecting of Impressionism: National to Euro-American to Global Richard R. Brettell, Founding Director and Margaret McDermott Distinguished Chair, Edith O’Donnell Institute of Art History; Co-Director, Center for the Interdisciplinary Study of Museums, The University of Texas at Dallas 4:30 “This kind of painting sells!”: Collectors of Impressionist Painting 1874-1914 Anne Distel, Curator Emerita, French National Museums, Paris 5:00 coffee break 5:25 Paul Durand-Ruel: Promoting Impressionists Abroad Paul-Louis Durand-Ruel, Paris 5:55 The Inspiring Insider: Mary Cassatt and the Taste for Impressionism in America Laura D. Corey, Research Associate, European Paintings, The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York 6:25 questions from the audience saturday, may 12 10:30 registration 10:45 welcome Inge Reist 11:00 Monet-Mania: Boston Encounters Impressionism George T. M. Shackelford, Deputy Director, Kimbell Art Museum, Fort Worth 11:30 Sara Tyson Hallowell: Art Advisor to Bertha and Potter Palmer, Chicago Collectors in the Gilded Age Carolyn Carr, Deputy Director and Chief Curator Emerita, National Portrait Gallery, Smithsonian Institution, Washington, D.C. 12:00 coffee break 12:20 England’s Reluctant Reception of Modern French Art Christopher Riopelle, The Neil Westreich Curator of Post-1800 Paintings, National Gallery, London 12:50 Collecting French Impressionism in Imperial Germany Thomas W. -

Curriculum Vitae

CURRICULUM VITAE Richard Robson Brettell, Ph.D. School of Arts and Humanities Margaret McDermott Distinguished Chair Arts & Aesthetics The University of Texas at Dallas 800 West Campbell Road Richardson, TX 75080-3021 973-883-2475 Education: Yale University, B.A., M.A., and Ph.D. (1971,1973,1977) Employment: Margaret McDermott Distinguished Chair of Art and Aesthetics, The University of Texas at Dallas, 1998- Independent Art Historian and Museum Consultant, 1992- American Director, FRAME, French Regional & American Museum Exchange, 1999- McDermott Director, The Dallas Museum of Art, 1988-1992 Searle Curator of European Painting, The Art Institute of Chicago, 1980-1988 Academic Program Director/Assistant Professor, Art History, Art Department, The University of Texas, Austin, 1976-1980 Other Teaching: Visiting Professor, Fine Arts Harvard University, spring term, 1995 Visiting Professor, The History of Art, Yale University, spring term, 1994 Adjunct Professor of Art History The University of Chicago, 1982-88 Visiting Instructor, Northwestern University, 1985 Fellowships: Visiting Scholar, The Clark Art Institute, Summers of 1996-2000 Visiting Fellow The Getty Museum, 1985 National Endowment for the Humanities Summer Fellow, 1980 Professional Affiliations: Chairman (1990) and Member, The United States Federal Indemnity Panel, 1987-1990 The Getty Grant Program Publication Committee 1987-1991 The American Association of Museum Directors 1988-93 The Elizabethan Club The Phelps Association Boards: FRAME (French Regional American Museum Exchange) Trustee 2010- The Dallas Architecture Forum, 1997-2004 (Founder and first president) The Georgia O'Keeffe Foundation 1989-1995 Dallas Artists Research and Exhibitions, 1990- (founder and current president) The College Art Association 1986-9 Museum of African-American Life and Culture, 1988-1992 The Arts Magnet High School, Dallas, Texas, 1990-1993 Personal Recognition: Dr. -

Art Seminar Group

7/16/2020 Art Seminar Group Please retain for your records SUMMER • AUGUST 2020 Tuesday, August 4, 2020 GUESTS WELCOME 1:30 pm via Zoom Pissarro on Pissarro: Camille Pissarro's Worlds Joachim Pissarro, Bershad professor of art history and director of the Hunter College Galleries, Hunter College, CUNY/City University of New York. This talk will provide a unique look into Joachim Pissarro’s personal journey in discovering the work and personality of his great-grandfather Camille Pissarro. Joachim Pissarro will help us explore Camille Pissarro’s complex phenomenal imagination, an unusually rich, innovative visual mind, a vast curiosity about techniques of all sorts, an open mind towards his colleagues, and a strongly defined set of intellectual positions. Joachim Pissarro is currently the Bershad Professor of Art History and Director of the Hunter College Galleries, Hunter College, CUNY/City University of New York. He was a Curator at MoMA’s Department of Painting and Sculpture. His teaching and writing presently focus on the challenges facing art history due to the unprecedented proliferation of art works, images, and visual data. He co-authored a book on this topic with David Carrier, entitled Wild Art. In the same vein, he also taught a seminar on Michael Jackson: The Contemporary Representation of a Cultural Icon. He curated the show “Klein & Giacometti: In search of the Absolute in the Era of Relativity” at Gagosian Gallery London in summer 2016. His latest book is titled Wild Art (Phaidon) and his forthcoming book (Penn State University) is co-authorized with David Carrier. He has had two major exhibitions in Paris in 2017, Pissarro à Eragny at the Musée du Luxembourg along with his catalogue essay L’Eragny de Pissarro (co-authored with Alma Egger) and Olga Picasso at the Musée Picasso, Paris along with his catalogue essay Il n’ya pas eu d’époque néo-classique chez Picasso—seulement une époque Olga. -

Bloch Galleries: 19Th -Century and 20Th -Century European Painting

Library Guide Bloch Galleries: 19th -Century and 20th -Century European Painting Resource List | March 2017 Vincent van Gogh, Dutch (1853-1890). Restaurant Rispal at Asnières, 1887. Oil on canvas, 28 7/8 x 23 5/8 inches. Gift of Henry W. and Marion H. Bloch, 2015.13.10. The art of the nineteenth century includes the first major movements and styles of modern art. Spanning many different styles from Neoclassicism and Romanticism through the early 20th century, including Expressionism, Dada and Surrealism, this bibliography presents a survey of resources on European painting of the nineteenth century. We have included titles on the different art movements of the period, and works about individual artists featured in the Bloch Galleries. A selection of general resources concludes the listing. If you have questions, please contact the reference staff at the Spencer Art Reference Library (telephone: 816.751.1216). Library hours and services are listed on the Museum’s website at www.nelson-atkins.org Selected by: Roberta Wagener | Library Assistant, Public Services Collection Catalogues Brettell, Richard R. and Joachim Pissarro. Manet Gerstein, Marc S. and Richard R. Brettell. to Matisse: Impressionist Masters from the Marion and Impressionism: Selections from Five American Henry Bloch Collection. Kansas City: The Nelson- Museums. New York: Hudson Hills Press, 1989. Atkins Museum of Art, 2007. Call No: Reading Room N582 .K31 1990 no. 1 Call No: Reading Room N582 .K31 2007 no. 2 Library Resource List 2017 | Bloch Galleries | 1 Major Art Movements in the Bloch Galleries Impressionism British Portraiture Brettell, Richard R. Impression: Painting Quickly in Garstang, Donald, ed. -

The Medium Fall/Winter 1997 the Medium the Newsletter of the Texas Chapter of Arlis/Na Volume 23 Number 3/4 Faluwinter 1997

THE MEDIUM FALL/WINTER 1997 THE MEDIUM THE NEWSLETTER OF THE TEXAS CHAPTER OF ARLIS/NA VOLUME 23 NUMBER 3/4 FALUWINTER 1997 PRESIDENT'S COLUMN Well, it's that time of year again. We've eaten our fill of turkey and pumpkin pie and are preparing for the Holidays. It is also the time of year for the last issue of The Medium and reports on our annual chapter meeting which was held this year in Houston, October 9 through 11. I hope that everyone who had the opportunity to attend had a wonderful time. We have a great group of members in Houston, both old and new, who really rallied together to put together an activity-filled meeting. I am very grateful for all of their help and really enjoyed our two organizing lunches in the weeks before the chapter meeting. Jacqui Allen arranged the two delicious dinners at River Cafe and Baba Yega. Phil Heagy organized a delightful tour of The Menil Collection and it's environs, including St. Basil's Chapel at The University of St. Thomas. Jet Prendeville and Margaret Culbertson developed a great walking tour of Rice University's architecture, which Jet lead to perfection. Trish Garrison, one of our new members, arranged for Friday's lunch to be catered by the culinary students at The Art Institute of Houston. Jeannette Dixon and Margaret Culbertson took part in our trial effort at an AskARLIS/Texas session. Jon Evans, another new member, gathered local information and sight-seeing materials for the registration packets. Margaret Ford posted meeting information and last-minute updates onto our chapter web page. -

Impressionist Gardens

Impressionist Gardens 2010-07-31 2010-10-17 Objects proposed for protection under Part Six of the Tribunals, Courts and Enforcement Act 2007 (Protections of cultural objects on loan from outside the UK). Metropolitan Museum of Art, 1000 Fifth Avenue, New York NY10028, USA Type of work: Painting Title: Garden Scene Date Created: 1854 Maker: Jean-Francois Millet Maker dates: 1814 - 1875 Nationality: French Dimensions: 17.1 x 21.3 cm (framed: 41.3 x 46.4 x 7.6 cm) Materials: Oil on canvas Identifying Signed (lower right): J. F. Millet. marks: Place of Not recorded manufacture: Ownership Metropolitan Museum of Art 1933 - 1945: Provenance: Morris K. Jesup, New York (until d. 1908); his widow, Maria DeWitt Jesup, New York (1908-d. 1914) Exhibition New York. The Metropolitan Museum of Art. "Barbizon: French Landscapes of the history: Nineteenth Century," February 4-May 10, 1992, no catalogue. Albany. New York State Museum. "French Painters of NAture; The Barbizon SChool: Landscapes from the MEtropolitan Museum of Art," May 22-August22, 2004, no catalogue. Publications: Robert L. Herbert. Letter to Mrs. Leonard Harris. January 19, 1962. Charles Sterling and Margretta M. Salinger. "XIX Century." French Paintings: A Catalogue of the Collection of The Metropolitan Museum of Art. 2, New York, 1966, p. 89, ill. Page 1 of 19 Impressionist Gardens 2010-07-31 2010-10-17 Objects proposed for protection under Part Six of the Tribunals, Courts and Enforcement Act 2007 (Protections of cultural objects on loan from outside the UK). Type of work: Painting Title: The Parc Monceau Date Created: 1878 Maker: Claude Monet Maker dates: 1840 - 1926 Nationality: French Dimensions: 72.7 x 54.3 cm (framed: 98.4 x 79.7 x 10.8 cm) Materials: Oil on canvas Identifying Signed and dated (lower right): Claude Monet 78 marks: Place of Not recorded manufacture: Ownership The work was seized by Nazis 1940 but restituted to Lindon Family 1946 1933 - 1945: see Provenance for details. -

GEORGE CONDO with Joachim Pissarro

ART INCONVERSATION GEORGE CONDO with Joachim Pissarro November 2, 2017 George Condo, Double Heads Drawing 7, 2015. Charcoal, pastel, and graphite on paper, 26 1/4 × 40 1/4 in. Private collection. Courtesy Skarstedt Gallery and Sprüth Magers. George Condo is a New York-based artist whose career launched in the East Village in the early 1980s. During this time, he also worked in Andy Warhol’s factory before moving to Los Angeles and holding his first solo exhibition in 1983. In the decades that followed, Condo has emerged as one of the world’s preeminent painters and sculptors. In 2017, the Skarstedt Gallery in New York presented a selection of new works, while the Philips Collection in Washington, DC., mounted a major drawings retrospective that will open at the Louisiana Museum of Modern Art in Denmark this November. Joachim Pissarro sat down with George Condo to discuss his works, his travels, and the “influenza” of influence. Portrait of George Condo, pencil on paper by Phong Bui. Joachim Pissarro (Brooklyn Rail): You said something—I think this was after your bout with cancer: “I was in five places at once.” It almost seems that lately you have been in more than five places at once. How do you do so much? George Condo: I suppose it’s just my compulsive nature; I don’t have anything else to do that's better. I have no patience for spending time meaninglessly. Like this morning I woke up, had a coffee, made a couple of drawings—and it was only 7:15—and I thought, “Now what am I supposed to do?” So then I thought, “Okay, maybe I’ll have some eggs,” and then I thought, “I’ll go work on a little painting.” Now it’s about 9:00, I’m gonna get in the car and go down to my studio, and we’re gonna do a few more things and work, and I won’t be able to work all day. -

7 X 11.5 Three Lines.P65

Cambridge University Press 978-0-521-83640-1 - Cezanne/Pissarro, Johns/Rauschenberg: Comparative Studies on Intersubjectivity in Modern Art Joachim Pissarro Frontmatter More information CEZANNE/PISSARRO,´ JOHNS/RAUSCHENBERG: COMPARATIVE STUDIES ON INTERSUBJECTIVITY IN MODERN ART This book presents a comparative study of two pairs of collaborative artists who worked closely with one another for years. The first pair, Cezanne´ and Pissarro, contributed to the emergence of modernism. The second pair, Johns and Rauschenberg, contributed to the demise of modernism. In each case, the two artists entered into a rich and challenging artistic exchange and reaped enormous benefits from this interaction. Joachim Pissarro’s comparative study suggests that these interactive dialogues were of great significance for each artist. Taking a cue from philosophers Immanuel Kant and Johann Gottlieb Fichte, he suggests that the individual is the result of reciprocal encounters: he argues that modern subjectivity is essentially open to others (intersubjective). Paradoxically, the modernist tradition has largely presented each of these four artists in isolation. This book thus also offers a critique of modernism as a monological ideology that resisted thinking about art in plural terms. Joachim Pissarro is a curator in the Department of Painting and Sculpture at The Museum of Modern Art, New York. He is the author of many articles and books on aspects of modern art from the late nineteenth to the late twentieth centuries, and he has contributed to several exhibition -

Wangechi Mutu

WANGECHI MUTU Born 1972 in Nairobi, Kenya Works in New York, USA and Nairobi, Kenya Education 2000 MFA Sculpture, Yale University School of Art, New Haven, CT, USA 1996 BFA, Cooper Union for the Advancement of the Arts and Science, New York, NY, USA 1991 I.B. United World College of the Atlantic, Wales, UK Solo Exhibitions 2019 The Met Facade Commission: Wangechi Mutu, The NewOnes will free Us, Metropolitan Museum, New York, USA (2019-2020) 2018 A Promise to Communicate, Institute of Contemporary Art Boston, Boston, MA, USA Wangechi Mutu: The End of eating Everything, Blanton Museum of Art, Austin, TX, USA 2017 Water Woman, The Contemporary Austin, TX, USA Wangechi Mutu, Lehmann Maupin, Hong Kong, China Ndoro Na Miti, Barbara Gladstone Gallery, New York, USA Banana Stroke, Performa 17 Biennial, The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York, USA Journeys into Peripheral Worlds, Des Moines Art Center, Des Moines, USA 2016 The End of Carrying All, Museum of Fine Arts, Houston, TX, USA Solo installation, Yale University Art Gallery, New Haven, CT, USA SITE 20 Years / 20 Shows Spring 2016, SITE Santa Fe, NM, USA The Hybrid Human, Arlene and Harold Schnitzer Center for Art and Design, Pacific Northwest College of Art Center for Contemporary Art and Culture, Portland, Oregon, USA 2015 Wangechi Mutu, Il Capricorno, Venice, Italy 2014 Nguva na Nyoka (Sirens and Serpents), Victoria Miro Gallery, London, UK 2013 Wangechi Mutu: A Fantastic Journey, Nasher Museum of Art at Duke University, Durham, North Carolina; touring to Brooklyn Museum of Art, New York; Museum of Contemporary Art, North Miami; Mary and Leigh Block Museum, Northwestern University, Illinois (2014) Wangechi Mutu, Museum of Contemporary Art, Sydney, Australia; touring to Orange County Museum, California, USA Wangechi Mutu , Leonard Pearlstein Gallery, Drexel University, Philadelphia, PA, USA 2012 Nitarudi Ninarudi I plan to return I am returning, Susanne Vielmetter L.A. -

The Cypress Trees in "The Starry Night": a Symbolic Self-Portrait of Vincent Van Gogh

Providence College DigitalCommons@Providence Art & Art History Student Scholarship Art & Art History Fall 2010 The Cypress Trees in "The Starry Night": A Symbolic Self-Portrait of Vincent Van Gogh Jessica Caldarone Providence College Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.providence.edu/art_students Part of the Ancient, Medieval, Renaissance and Baroque Art and Architecture Commons, Art and Design Commons, Modern Art and Architecture Commons, Other History of Art, Architecture, and Archaeology Commons, and the Theory and Criticism Commons Caldarone, Jessica, "The Cypress Trees in "The Starry Night": A Symbolic Self-Portrait of Vincent Van Gogh" (2010). Art & Art History Student Scholarship. 3. https://digitalcommons.providence.edu/art_students/3 It is permitted to copy, distribute, display, and perform this work under the following conditions: (1) the original author(s) must be given proper attribution; (2) this work may not be used for commercial purposes; (3) users must make these conditions clearly known for any reuse* or distribution of this work. *Reuse of included images is not permitted. THE CYPRESS TREES IN “THE STARRY NIGHT”: A SYMBOLIC SELF-PORTRAIT OF VINCENT VAN GOGH Jessica Caldarone Principles of Research/ARH 498-001 1 Vincent van Gogh was born in 1853 in the Netherlands. His experience with the art world began when he started working for his uncle’s art firm at the age of seventeen.1 Along with his brother Theo, Van Gogh was employed by the Goupil House in The Hague, the Netherlands, which dealt with French and Dutch art of the time.2 However, the influence of Van Gogh’s father, a Protestant pastor, led Van Gogh to leave the firm to pursue studies in theology and missionary work.3 Because he did not display the appropriate qualities necessary for a missionary, Van Gogh was let go from his evangelical work,4 which then led to his decision to become an artist. -

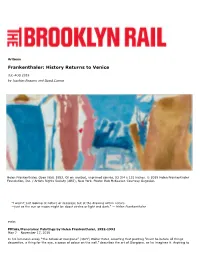

History Returns to Venice – the Brooklyn Rail

ArtSeen Frankenthaler: History Returns to Venice JUL-AUG 2019 by Joachim Pissarro and David Carrier Helen Frankenthaler, Open Wall, 1953. Oil on unsized, unprimed canvas, 53 3/4 x 131 inches. © 2019 Helen Frankenthaler Foundation, Inc. / Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York. Photo: Rob McKeever. Courtesy Gagosian. “I wasn’t just looking at nature or seascape but at the drawing within nature —just as the sun or moon might be about circles or light and dark.” — Helen Frankenthaler Venice Pittura/Panorama: Paintings by Helen Frankenthaler, 1952-1992 May 7 – November 17, 2019 In his luminous essay “The School of Giorgione” (1877) Walter Pater, asserting that painting “must be before all things decorative, a thing for the eye, a space of colour on the wall,” describes the art of Giorgione, as he imagines it. Aspiring to the condition of music, this art aspires “to get rid of its responsibilities to its subject or material,” and thus achieve a “perfect identification of matter and form.” It’s hard to imagine a better prophecy of the painting of Helen Frankenthaler, whose magnificent show on the second floor of Palazzo Grimani, in Santa Maria Formosa a short walk from San Marco included fourteen large, mostly horizontally oriented works. Organized by Helen Frankenthaler Foundation and Venetian Heritage, in collaboration with Gagosian, it was curated by John Elderfield. The second half of the twentieth century opened in New York with a couple of works that signaled a total sea change in the, then indeed, fast shifting art world: Robert Rauschenberg’s White Paintings, executed in 1950, and a couple of years later, Helen Frankenthaler’s Mountains and Sea, 1952. -

Van Gogh's Last Supper: Transforming

Anistoriton Journal, vol. 14 (2014‐2015) Viewpoints Van Gogh’s Last Supper Transforming “the guise of observable reality” Although little has been written about Café Teras (Fig. 1), it has enraptured the imagination of the general public, becoming one of the world’s most reproduced paintings (Reynolds 2010). Perhaps the accepted, superficial interpretations of this seemingly casual street scene: that it is “something like” the opening description of “drinkers in the harsh, bright lights of their illuminated facades” from Guy de Maupassant’s Bel-Ami (Jansen et al. 2009, l. 678, n. 15) or homage to Louis Anquetin’s Avenue de Clichy: 5 o’clock in the Evening (Welsh- Ovcharov 1981); coupled by the relatively scant description in van Gogh’s existing letters and 20th century art critic Dr. Meyer Schapiro’s slight that it may be “less concentrated than the best of van Gogh” (1980 p. 80), have undermined a more thorough investigation of this luminous subject. ( F(Fig. 1 Café Teras) (Fig. 2 Café Teras, Sketch) Nevertheless, this lack of inquiry seems peculiar for a number of reasons. 1) Café Teras was conceived over several months during his self-imposed isolation in Arles, a time when Vincent, feeling marginalized and alienated, ceaselessly schemed to reconnect with his copains Émile Bernard, Paul Gauguin and others, hoping to found a kind of Pre-Raphaelite brotherhood of twelve “artist-apostles” who, communally, would forge the new Renaissance. 2) It is Vincent’s original “starry night,” composed “on the spot,” painstakingly crafted over several nights while he reported feeling a “terrible need for religion” (Jansen et al.