A Phenomenology of Americans and Anime: How Tropes Predict Experience

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Protoculture Addicts #65

Sample file CONTENTS 3 ○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○ PROTOCULTURE ✾ PRESENTATION ........................................................................................................... 4 STAFF NEWS ANIME & MANGA NEWS ........................................................................................................ 5 Claude J. Pelletier [CJP] — Publisher / Manager ANIME & MANGA RELEASES ................................................................................................. 6 Martin Ouellette [MO] — Editor-in-Chief PRODUCTS RELEASES ............................................................................................................ 8 Miyako Matsuda [MM] — Editor / Translator NEW RELEASES ..................................................................................................................... 11 Contributors Aaron & Keith Dawe, Kevin Lillard, James S. Taylor REVIEWS LIVE-ACTION ........................................................................................................................ 16 Layout BOOKS: Gilles Poitras' Anime Essentials ................................................................................. 18 The Safe House MODELS: Comparative Review Bendi/Bandai, Perfect Grade Gundam W ................................ 32 MANGA: ComicsOne manga & The eBook Technology .......................................................... 46 Cover MANGA: Various (English & French) ...................................................................................... -

TV Review: "The Great" - UCSD Guardian

Accessed: 6/10/2020 TV Review: "The Great" - UCSD Guardian To learn more about The UCSD Guardian's coverage of the COVID-19 pandemic, click here → TV Review: “The Great” May 25, 2020 Chloe Esser “The Great” doesn’t care about history, and neither should you. From creator of “The Favourite” Tony McNamara comes another historical retelling that slides right out of the conventions typically associated with the period drama genre into a terribly clever, terrifically dark piece of its own. “The Great” covers Russian empress Catherine the Great’s rise to power as a teenage girl — with some massive liberties. The show neatly balances the courtly decadence and subtle power plays of “The Favourite” with the blood, sex, and quick wit that’s to be expected in a world where all historical dramas must compete to be the next “Game of Thrones.” Nevertheless, it’s a well-maintained balance. Heavily stylized, effortlessly witty, and maybe a bit needlessly obscene, “The Great” is a show that knows exactly what it is, whether or not that has anything to do with actual history. The show begins with German teenager Catherine (Elle Fanning), who has come to Russia to marry a man she has never met –– Emperor Peter III (Nicholas Hoult). An idealist and intellectual caught up in the wave of Europe’s Enlightenment, Catherine has big plans for Accessed: 6/10/2020 TV Review: "The Great" - UCSD Guardian her new home, and she is disappointed to find a court more concerned with hunting, sex, and booze than discussing the latest Voltaire. -

The Portrayal of Suicide in Postmodern Japanese Literature and Popular Culture Media

University of Vermont ScholarWorks @ UVM UVM Honors College Senior Theses Undergraduate Theses 2014 The orP trayal of Suicide in Postmodern Japanese Literature and Popular Culture Media Pedro M. Teixeira Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarworks.uvm.edu/hcoltheses Recommended Citation Teixeira, Pedro M., "The orP trayal of Suicide in Postmodern Japanese Literature and Popular Culture Media" (2014). UVM Honors College Senior Theses. 15. https://scholarworks.uvm.edu/hcoltheses/15 This Honors College Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by the Undergraduate Theses at ScholarWorks @ UVM. It has been accepted for inclusion in UVM Honors College Senior Theses by an authorized administrator of ScholarWorks @ UVM. For more information, please contact [email protected]. THE PORTRAYAL OF SUICIDE IN POSTMODERN JAPANESE LITERATURE AND POPULAR CULTURE MEDIA Pedro Manço Teixeira Honors Thesis Final Draft, Spring 2014 Thesis Advisor: Kyle Keoni Ikeda INTRODUCTION Within Japanese society, suicide has been a recurring cultural and social concern explored extensively in various literary and artistic forms, and has evolved into a serious societal epidemic by the end of the 20 th century. This project investigates contemporary Japan’s suicide epidemic through an analysis of the portrayal of suicide in post-1970s Japanese literature, films, and popular culture media of manga 1 and anime 2, and in comparison to empirical data on suicide in Japan as presented in peer-reviewed psychology articles. In the analysis of these contemporary works, particular attention was given to their targeted demographic, the profiles of the suicide victims in the stories, the justifications for suicide, and the relevance of suicide to the plot of each work. -

Rasa Memiliki Dalam Komunitas Cosplay Skripsi

UNIVERSITAS INDONESIA RASA MEMILIKI DALAM KOMUNITAS COSPLAY SKRIPSI KARINA AISYAH 0806394532 FAKULTAS ILMU PENGETAHUAN BUDAYA PROGRAM STUDI JEPANG DEPOK JULI 2012 Rasa memiliki..., Karina Aisyah, FIB UI, 2012 UNIVERSITAS INDONESIA RASA MEMILIKI DALAM KOMUNITAS COSPLAY SKRIPSI Diajukan sebagai salah satu syarat untuk memperoleh gelar Sarjana Humaniora KARINA AISYAH 0806394532 FAKULTAS ILMU PENGETAHUAN BUDAYA PROGRAM STUDI JEPANG DEPOK JULI 2012 Rasa memiliki..., Karina Aisyah, FIB UI, 2012 Rasa memiliki..., Karina Aisyah, FIB UI, 2012 Universitas Indonesia Rasa memiliki..., Karina Aisyah, FIB UI, 2012 KATA PENGANTAR Alhamdulillah penulis panjatkan kepada Allah SWT atas segala ridho dan berkah dari-Nya, sehingga skripsi ini dapat diselesaikan. Skripsi ini ditulis dalamrangka memenuhi salah satu syarat untuk meraih gelar Sarjana Humaniora Program Studi Jepang pada Fakultas Ilmu Pengetahuan Budaya Universitas Indonesia. Penulis juga ingin berterima kasih kepada berbagai pihak yang telah membantu proses pengerjaan skripsi ini, yaitu: 1) Keluarga penulis yang dengan dukungan baik moral maupun materi, Ayah, Ibu, keceriaan dan dukungan semangat kedua adik penulis, Fanny dan Via, serta seluruh keluarga besar, khususnya Ama dan Mbah yang selalu mendoakan perjuangan penulis. 2) Dr. Bachtiar Alam selaku pembimbing skripsi. 3) Ibu Sri Wulansari yang memberikan saran dan kritik yang membantu, serta selalu menyemangati penulis dan telah meluangkan waktu untuk membaca dan menguji skripsi ini. 4) Bapak Jonnie Rasmada Hutabarat, selaku Ketua Program Studi Jepang FIB UI. 5) Seluruh dosen dan staf pengajar Program Studi Jepang FIB UI yang selama masa studi penulis telah memberikan banyak ilmu yang bermanfaat. お世話になりました。本当にありがとうございました! 6) Sahabat penulis, Marcella Mamengko yang telah memberikan semangat dan mencurahkan perhatian yang tidak terhingga kepada penulis dan bersama – sama berjuang menyelesaikan skripsi. -

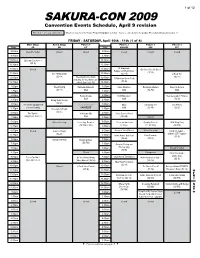

Sakura-Con 2009

1 of 12 SAKURA-CON 2009 FRIDAY - SATURDAY, April 10th - 11th (2 of 4) FRIDAY - SATURDAY, April 10th - 11th (3 of 4) FRIDAY - SATURDAY, April 10th - 11th (4 of 4) Convention Events Schedule, April 9 revision Panels 5 Fan Workshop 1 Fan Workshop 2 Autographs Console Gaming Music Gaming Anime Theater 1 Anime Theater 2 FUNimation Theater Anime Music Video Classic Anime Theater Live-Action Theater Fansub Theater Karaoke Collectible Card Miniatures Gaming Tabletop Gaming Cosplay Photo 3AB 204 205 Time 4B 4C-3,4 4C-1 Time Time 611-612 615-617 618-620 Time Theater: 6A 604 613-614 310 2AB Time Gaming: 307-308 305 306 Gatherings (Location) Time Bold text in a heavy outlined box indicates revisions to the Pocket Programming Guide schedule. Also see corrections to the Cosplay Photo Gathering locations on p. 11. Closed Closed Closed 7:00am Closed Closed Closed 7:00am 7:00am Closed Closed Closed 7:00am Closed Closed Closed Closed Closed 7:00am Closed Closed Closed See p. 11 for the key 7:00am 7:30am 7:30am 7:30am 7:30am 7:30am to photo shoot locations. 7:30am FRIDAY - SATURDAY, April 10th - 11th (1 of 4) 8:00am 8:00am 8:00am Elemental Gelade 1-5 To Heart 1-4 Fate/stay night 1-3 8:00am Voltron 1-5 New Legend of Shaolin Haruka Nogizaka’s Secret Closed for setup 8:00am 8:00am Main Stage Arena Stage Panels 1 Panels 2 Panels 3 Panels 4 (SC-PG V, dub) (SC-PG D, sub) (SC-PG VS, dub) (SC-PG V, dub) (SC-14) 1-4 4A 6E 6C 608-609 606 607 8:30am 8:30am 8:30am 8:30am 8:30am 8:30am Time Time (SC-PG SD) Koichi Ohata Showcase: 9:00am Closed for setup Closed Closed -

Protoculture Addicts Is ©1987-2004 by Protoculture

Sample file CONTENTS 3 ○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○ P r o t o c u l t u r e A d d i c t s # 8 0 January / February 2004. Published bimonthly by Protoculture, P.O. Box 1433, Station B, Montreal, Qc, ANIME VOICES Canada, H3B 3L2. Web: http://www.protoculture-mag.com Presentation ............................................................................................................................ 4 Letters ................................................................................................................................... 70 E d i t o r i a l S t a f f Claude J. Pelletier [CJP] – Publisher / Editor-in-chief [email protected] NEWS Miyako Matsuda [MM] – Editor / Translator ANIME & MANGA NEWS: Japan ................................................................................................. 5 Martin Ouellette [MO] – Editor ANIME RELEASES (VHS / R1 DVD) .............................................................................................. 6 PRODUCTS RELEASES (Live-Action, Soundtracks) ......................................................................... 7 C o n t r i b u t i n g E d i t o r s MANGA RELEASES .................................................................................................................... 8 Asaka Dawe, Keith Dawe, Kevin Lillard, James S. Taylor MANGA SELECTION .................................................................................................................. 8 P r o d u c t i o n A s s i s t a n t s ANIME & MANGA NEWS: North -

DIABC SUMMER 2006.Indd

BOOKS AND TRADE PAPERBACKS TABLE OF CONTENTS 13th Son: Worse Thing Waiting . 44 Oh My Goddess! Volume 3 . 30 Aeon Flux . 21 Old Boy Volume 1 . 50 The Artist Within . 43 Path of the Assassin Volume 1 . 31 B.P.R.D.: The Black Flame . 39 Penny Arcade Volume 2: Epic Legends Berserk Volume 12 . 32 of the Magic Sword Kings . 49 BMWFilms.com Presents The Hire . 20 Pete Von Sholly’s Cannon God Exaxxion Stage 5 . 55 Extremely Weird Stories . 42 The Comics: An Illustrated History of Reiko the Zombie Shop Volume 3 . 26 Comic Strip Art . 43 Revelations . 44 Conan and the Demons of Khitai . 36 Saiyuki Reload Anime Manga Conan Volume 3: The Tower Volume 1 . 53 of the Elephant and Other Stories . 37 Scary Book Volume 2: Insects . 18 Concrete Volume 5: School Zone Volume 2 . 35 Think Like a Mountain . 20 Star Wars Omnibus: Concrete Volume 6: Strange Armor . 41 X-Wing Rogue Squadron Volume 1 . 23 Crying Freeman Volume 2 . 26 Star Wars: Clone Wars Adventures Ctrl-Alt-Del Volume 3. 46 Volume 6 . 48 De:Tales . 38 Star Wars: Clone Wars Dreadlful Ed . 24 Volume 9—Endgame . 48 Eden: It’s an Endless World! Volume 3 . 18 Star Wars: Honor and Duty . 22 Eden: It’s an Endless World! Volume 4 . 50 Sudden Gravity . 38 Emily the Strange Volume 1 . 45 Tarzan: The Joe Kubert Years Volume 3 . 36 Go Girl!: Robots Gone Wild! . 55 Trigun Maximum Volume 9 . 19 Gungrave Archive . 27 Trigun Maximum Volume 10 . 53 Haibane Renmei Anime Manga . 19 Usagi Yojimbo: Volume 20 Harlan Ellison’s Dream Corridor Glimpses of Death . -

Copyright by Ross Christopher Feldman 2011

Copyright by Ross Christopher Feldman 2011 The Thesis Committee for Ross Christopher Feldman Certifies that this is the approved version of the following thesis: ENCHANTING MODERNITY: RELIGION AND THE SUPERNATURAL IN CONTEMPORARY JAPANESE POPULAR CULTURE APPROVED BY SUPERVISING COMMITTEE: Supervisor: Kirsten C. Fischer John W. Traphagan ENCHANTING MODERNITY: RELIGION AND THE SUPERNATURAL IN CONTEMPORARY JAPANESE POPULAR CULTURE by Ross Christopher Feldman, B. A. Thesis Presented to the Faculty of the Graduate School of The University of Texas at Austin in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of Master of Arts The University of Texas at Austin August 2011 ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS It seems an excess of hubris to attach acknowledgements to so short a work; nevertheless it would be remiss of me to fail to offer my thanks to those individuals whose support was indispensible to its creation. I would like to express my gratitude: To Dr. Kirsten Cather, my ever-patient adviser and mentor, and Dr. John Traphagan, my eagle-eyed second reader and generous counselor; To Dr. Oliver Freiberger and the faculty and staff of the Department of Asian Studies at the University of Texas at Austin; To Dr. Martha Newman and the faculty and staff of the Department of Religious Studies, particularly Jared Diener for his untiring support during my academic career at the University of Texas; To my family by birth and by marriage, whose support has been unwavering even when my work seemed obscure; And lastly, to the person without whom none of this could have been imagined, much less achieved; my greatest fount of ideas, sounding-board, copyeditor, critic, quality assurance technician, and support: my wife. -

“ FINNISH FANDOM of JAPANESE POPULAR CULTURE ” ~What Are the Finns Doing for Anime, Manga,And J-Rock?~

“ FINNISH FANDOM OF JAPANESE POPULAR CULTURE ” ~What are the Finns doing for anime, manga,and J-rock?~ Yoko Ishida Master’s Thesis Major subject/Digital Culture Department of Art and culture studies University of Jyväskylä Autumn 2010 JYVÄSKYLÄN YLIOPISTO Tiedekunta – Faculty Laitos – Department Humanities Art and Culture Studies Tekijä – Author Yoko Ishida Työn nimi – Title Finnish Fandom of Japanese Popular Culture Oppiaine – Subject Työn laji – Level Digital Culture MA Thesis Aika – Month and year Sivumäärä – Number of pages December 2010 85 pages Tiivistelmä – Abstract It has not been many years since the popularity of anime, manga and J-rock has risen in Finland. Especially, despite of limited availability of materials and small-scaled markets in Finland, there is a fascination among fans which has grown through the fan community via conventions and virtual networking. This paper will examine Japanese popular culture fandom, including situation of anime and manga, and J-rock in Finland. When/How they became the fans ? What the fans in Finland are doing, are they categorized as just “fans,” or “otaku” etc..? This research is not only because I am used to be fan of manga, J-rock but also it is fascinating t o observe the Japanese popular culture fandom since this subject has not yet been well-researched in Finland. For comparison and precedent, culture theory from similar studies in the U.S.A. can be used and this research will specifically focus on analysis of the interview with Finnish fan. The question this paper shall seek to answer is: What does it mean to be manga-anime- J-rock fan? How are the Finnish fans expressing their fandom? Moreover, among with fan activity, it shall focus on the virtual community and networking. -

Session Title Description a Sister's All You Need Every Day Is

Session Title Description Every day is full of fun. But something is missing. "My life would be amazing if only I had a little sister. Why don’t I have a little sister...?" These are the musings of little sister-lover and novelist Itsuki Hashima, who only writes works featuring little sisters. Around him gather a number of unique people: A Sister's All You Need genius author/pervert Nayuta, female college student Miyako, illustrator Puriketsu, and the brutish tax accountant Ashley. Each of them hold their own worries, but live their peaceful daily lives while writing novels, playing video games, drinking alcohol, and filing their tax returns. Ace Attorney English Dub Premiere WHO WOULD WIN?! It's a question that's plagued the American vs. Japanese Entertainment internet for years, but you've never seen it handled like this! The Ikkicon AMV League Contest! Come see some amazing AMV Contest videos, and find out which AMVs will be going on to compete for Best AMV of the Year What character would win in a fight? What's the best Shounen anime? Subbed or Dubbed? These questions burn Ani-battles: The Anime Debate Game to be answered and debated against your peers! Come play the ultimate anime debating game! Clannad, and its follow-up Clannad: After Story are some of the most emotional and beautifully produced examples of the medium, but there's a lot that happens in the story that makes Anime Ambush: What the Clannad?! it difficult to understand for the casual observer. In this panel, we'll be taking a look at the Key (heh, get it?) points in the storyline and discussing the various possibilities for the town of Hikarizaka. -

2004 Program Guide

Table of Contents ANIME BOSTON INBOUND 4 From the Con Chair 5 Guests of Honor 10 Events 12 Panels 18 Anime Programming 30 Live Programming 32 Convention Rules 40 Our Wonderful Staff 42 Food and Shops 44 Convention Maps Anime Boston 2004 3 From The Conchair One of the most enjoyable aspects of my job is that I get to write the opening letter to attendees every year in the guidebook, and this year is no exception. Once again I am thrilled to be able to be here with all of you this weekend as anime fans from all over the country return to the best city in America to illustration by Robertillustration by DeJesus celebrate our beloved hobby. Last year’s convention was a tremendous success and we have been actively trying to outdo ourselves this year. Just look at some of the changes in store for you: we’ve increased the size of the dealer’s room to over 75 tables and more than 25 vendors, we’ve doubled the size of the art show, we’ve ex- panded the video gaming room to include more consoles and a Dance Dance Revolution machine, we’ve increased the number of panel and video rooms, we’ve computerized registration, and we expanded our workshop and gam- ing tracks. We’ve also invited a whole new slate of guests to our convention. I am pleased to welcome Michael Coleman, Crispin Freeman, Lauren Goodnight, Hilary Haag, Carl Horn, Lex Lang, Monica Rial, and Dave Wittenberg. Returning guests include Robert and Emily DeJesus of Studio Capsule and David Williams, ADR director and DVD producer. -

October 2017

AJET News & Events, Arts & Culture, Lifestyle, Community OCTOBER 2017 Have you heard of...Yosakoi? Explore the history of one of Japan’s most celebrated traditional dances Raising funds, raising hopes - Join JETs on an annual expedition to Baan Unrak Children’s Home Bathing Thai Elephants - An alternative approach to wildlife tourism To leave, or not to leave? - Japan’s rising divorce levels as seen through contemporary drama Back to school bento recipes - Get inspired by our readers’ top DIY lunchbox tips! The Japanese Lifestyle & Culture Magazine Written by the International Community in Japan1 CREDITS & CONTENT HEAD EDITOR HEAD OF DESIGN & HEAD WEB EDITOR Lilian Diep LAYOUT Nadya Dee-Anne Forbes Ashley Hirasuna ASSITANT EDITOR ASSITANT WEB EDITOR Lauren Hill ASSISTANT DESIGNERS Amy Brown Connie Huang SECTION EDITORS Malia Imayama SOCIAL MEDIA Kirsty Broderick John Wilson Jack Richardson Michelle Cerami Shantel Dickerson COVER PHOTO Shantel Dickerson Hayley Closter Nicole Antkiewicz COPY EDITORS Verushka Aucamp Jasmin Hayward TABLE OF CONTENTS Tresha Barrett PHOTO Hannah Varacalli Bailey Jo Josie Duncan Cox Abby Ryder-Huth CONTRIBUTORS Sabrina Zirakzadeh ART & PHOTOGRAPHY Manabu Ohara Jocelyn Russell Manabu Ohara Ben Baer Ben Baer Josh Mangham Josh Mangham Jonathan Longden Jonathan Longden Farrah Hasnain Luke Paisley J. Colón Rachel Ristine Devyn Couch Kendra Spring Klasek Reece Mathiesen Sarah Laverty Rachel Ristine Ashley Hirasuna Kendra Spring Klasek Shantel Dickerson Sarah Laverty Duncan Cox Hannah Martin Illaura Rossiter Austin Neill on Unsplash Luke Paisley (illustrator) J. Colón Kris Atomic on Unsplash This magazine contains original photos used with permission, as well as free-use images. All included photos are property of the author unless otherwise specified.