Copyright by Ross Christopher Feldman 2011

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Miko Mido Is Lady Blue - Volume 1

Miko Mido is Lady Blue - Volume 1 Well then, i'll start off by conveying an old-fashioned La Blue Young lady event. This animated typically teeters in between excellent and very inadequate while using the infrequent awful continuity, super-hero plot of land gaps as well as over- all lazy specifics. All of this seemed to be overshadowed nevertheless by simply whatever else . a show needed to offer you: lengthy, useful or perfectly thought-out clips of eroticism promising range a occurrence (at times it's People on Human, sometimes its Enormous about Man, Tentacle on Our, Forms of martial arts Love- making, Bondage, Adult sex toys and Units... almost any lawful fetish). What's even better, Are generally Pink Woman has not been the sort of Hentai that put together it's violence featuring its sexuality, at least steer clear every single scene; in flashbacks and story/drama similar clips, there initially were relegations, but that was only if Kan Fukumoto arrived straight into primary. Usually it turned out great, exciting perversion in places you did not have to be concerned about young women bolstering when a hot man-beast received ahold of them. That may be another thing a regular Are generally Violet Young lady tv show presented: Entertaining. Miko Mido is often aloof plus a excellent eliminate expert, although the woman has been constantly met with crazy, comedy cases owing to your ex dwarf ninja partner Nin-Nin as well as her oversexed more mature aunt; regardless if Miko was met with danger as well as conserving the girl's mates out of lovemaking harm, Miko was your comedic figure. -

The Popular Image of Japanese Femininity Inside the Anime and Manga Culture of Japan and Sydney Jennifer M

University of Wollongong Research Online University of Wollongong Thesis Collection University of Wollongong Thesis Collections 2009 The popular image of Japanese femininity inside the anime and manga culture of Japan and Sydney Jennifer M. Stockins University of Wollongong Recommended Citation Stockins, Jennifer M., The popular image of Japanese femininity inside the anime and manga culture of Japan and Sydney, Master of Arts - Research thesis, University of Wollongong. School of Art and Design, University of Wollongong, 2009. http://ro.uow.edu.au/ theses/3164 Research Online is the open access institutional repository for the University of Wollongong. For further information contact Manager Repository Services: [email protected]. The Popular Image of Japanese Femininity Inside the Anime and Manga Culture of Japan and Sydney A thesis submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the award of the degree Master of Arts - Research (MA-Res) UNIVERSITY OF WOLLONGONG Jennifer M. Stockins, BCA (Hons) Faculty of Creative Arts, School of Art and Design 2009 ii Stockins Statement of Declaration I certify that this thesis has not been submitted for a degree to any other university or institution and, to the best of my knowledge and belief, contains no material previously published or written by any other person, except where due reference has been made in the text. Jennifer M. Stockins iii Stockins Abstract Manga (Japanese comic books), Anime (Japanese animation) and Superflat (the contemporary art by movement created Takashi Murakami) all share a common ancestry in the woodblock prints of the Edo period, which were once mass-produced as a form of entertainment. -

Stephen Colbert's Super PAC and the Growing Role of Comedy in Our

STEPHEN COLBERT’S SUPER PAC AND THE GROWING ROLE OF COMEDY IN OUR POLITICAL DISCOURSE BY MELISSA CHANG, SCHOOL OF PUBLIC AFFAIRS ADVISER: CHRIS EDELSON, PROFESSOR IN THE SCHOOL OF PUBLIC AFFAIRS UNIVERSITY HONORS IN CLEG SPRING 2012 Dedicated to Professor Chris Edelson for his generous support and encouragement, and to Professor Lauren Feldman who inspired my capstone with her course on “Entertainment, Comedy, and Politics”. Thank you so, so much! 2 | C h a n g STEPHEN COLBERT’S SUPER PAC AND THE GROWING ROLE OF COMEDY IN OUR POLITICAL DISCOURSE Abstract: Comedy plays an increasingly legitimate role in the American political discourse as figures such as Stephen Colbert effectively use humor and satire to scrutinize politics and current events, and encourage the public to think more critically about how our government and leaders rule. In his response to the Supreme Court case of Citizens United v. Federal Election Commission (2010) and the rise of Super PACs, Stephen Colbert has taken the lead in critiquing changes in campaign finance. This study analyzes segments from The Colbert Report and the Colbert Super PAC, identifying his message and tactics. This paper aims to demonstrate how Colbert pushes political satire to new heights by engaging in real life campaigns, thereby offering a legitimate voice in today’s political discourse. INTRODUCTION While political satire is not new, few have mastered this art like Stephen Colbert, whose originality and influence have catapulted him to the status of a pop culture icon. Never breaking character from his zany, blustering persona, Colbert has transformed the way Americans view politics by using comedy to draw attention to important issues of the day, critiquing and unpacking these issues in a digestible way for a wide audience. -

The Origins of the Magical Girl Genre Note: This First Chapter Is an Almost

The origins of the magical girl genre Note: this first chapter is an almost verbatim copy of the excellent introduction from the BESM: Sailor Moon Role-Playing Game and Resource Book by Mark C. MacKinnon et al. I took the liberty of changing a few names according to official translations and contemporary transliterations. It focuses on the traditional magical girls “for girls”, and ignores very very early works like Go Nagai's Cutie Honey, which essentially created a market more oriented towards the male audience; we shall deal with such things in the next chapter. Once upon a time, an American live-action sitcom called Bewitched, came to the Land of the Rising Sun... The magical girl genre has a rather long and important history in Japan. The magical girls of manga and Japanese animation (or anime) are a rather unique group of characters. They defy easy classification, and yet contain elements from many of the best loved fairy tales and children's stories throughout the world. Many countries have imported these stories for their children to enjoy (most notably France, Italy and Spain) but the traditional format of this particular genre of manga and anime still remains mostly unknown to much of the English-speaking world. The very first magical girl seen on television was created about fifty years ago. Mahoutsukai Sally (or “Sally the Witch”) began airing on Japanese television in 1966, in black and white. The first season of the show proved to be so popular that it was renewed for a second year, moving into the era of color television in 1967. -

Protoculture Addicts

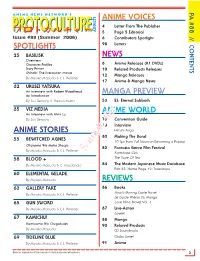

PA #88 // CONTENTS PA A N I M E N E W S N E T W O R K ' S ANIME VOICES 4 Letter From The Publisher PROTOCULTURE¯:paKu]-PROTOCULTURE ADDICTS 5 Page 5 Editorial Issue #88 (Summer 2006) 6 Contributors Spotlight SPOTLIGHTS 98 Letters 25 BASILISK NEWS Overview Character Profiles 8 Anime Releases (R1 DVDs) Story Primer 10 Related Products Releases Shinobi: The live-action movie 12 Manga Releases By Miyako Matsuda & C.J. Pelletier 17 Anime & Manga News 32 URUSEI YATSURA An interview with Robert Woodhead MANGA PREVIEW An Introduction By Zac Bertschy & Therron Martin 53 ES: Eternal Sabbath 35 VIZ MEDIA ANIME WORLD An interview with Alvin Lu By Zac Bertschy 73 Convention Guide 78 Interview ANIME STORIES Hitoshi Ariga 80 Making The Band 55 BEWITCHED AGNES 10 Tips from Full Moon on Becoming a Popstar Okusama Wa Maho Shoujo 82 Fantasia Genre Film Festival By Miyako Matsuda & C.J. Pelletier Sample fileKamikaze Girls 58 BLOOD + The Taste Of Tea By Miyako Matsuda & C. Macdonald 84 The Modern Japanese Music Database Part 35: Home Page 19: Triceratops 60 ELEMENTAL GELADE By Miyako Matsuda REVIEWS 63 GALLERY FAKE 86 Books Howl’s Moving Castle Novel By Miyako Matsuda & C.J. Pelletier Le Guide Phénix Du Manga 65 GUN SWORD Love Hina, Novel Vol. 1 By Miyako Matsuda & C.J. Pelletier 87 Live-Action Lorelei 67 KAMICHU! 88 Manga Kamisama Wa Chugakusei 90 Related Products By Miyako Matsuda CD Soundtracks 69 TIDELINE BLUE Otaku Unite! By Miyako Matsuda & C.J. Pelletier 91 Anime More on: www.protoculture-mag.com & www.animenewsnetwork.com 3 ○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○ LETTER FROM THE PUBLISHER A N I M E N E W S N E T W O R K ' S PROTOCULTUREPROTOCULTURE¯:paKu]- ADDICTS Over seven years of writing and editing anime reviews, I’ve put a lot of thought into what a Issue #88 (Summer 2006) review should be and should do, as well as what is shouldn’t be and shouldn’t do. -

Crossmedia Adaptation and the Development of Continuity in the Dc Animated Universe

“INFINITE EARTHS”: CROSSMEDIA ADAPTATION AND THE DEVELOPMENT OF CONTINUITY IN THE DC ANIMATED UNIVERSE Alex Nader A Thesis Submitted to the Graduate College of Bowling Green State University in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of MASTER OF ARTS May 2015 Committee: Jeff Brown, Advisor Becca Cragin © 2015 Alexander Nader All Rights Reserved iii ABSTRACT Jeff Brown, Advisor This thesis examines the process of adapting comic book properties into other visual media. I focus on the DC Animated Universe, the popular adaptation of DC Comics characters and concepts into all-ages programming. This adapted universe started with Batman: The Animated Series and comprised several shows on multiple networks, all of which fit into a shared universe based on their comic book counterparts. The adaptation of these properties is heavily reliant to intertextuality across DC Comics media. The shared universe developed within the television medium acted as an early example of comic book media adapting the idea of shared universes, a process that has been replicated with extreme financial success by DC and Marvel (in various stages of fruition). I address the process of adapting DC Comics properties in television, dividing it into “strict” or “loose” adaptations, as well as derivative adaptations that add new material to the comic book canon. This process was initially slow, exploding after the first series (Batman: The Animated Series) changed networks and Saturday morning cartoons flourished, allowing for more opportunities for producers to create content. References, crossover episodes, and the later series Justice League Unlimited allowed producers to utilize this shared universe to develop otherwise impossible adaptations that often became lasting additions to DC Comics publishing. -

The Significance of Anime As a Novel Animation Form, Referencing Selected Works by Hayao Miyazaki, Satoshi Kon and Mamoru Oshii

The significance of anime as a novel animation form, referencing selected works by Hayao Miyazaki, Satoshi Kon and Mamoru Oshii Ywain Tomos submitted for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy Aberystwyth University Department of Theatre, Film and Television Studies, September 2013 DECLARATION This work has not previously been accepted in substance for any degree and is not being concurrently submitted in candidature for any degree. Signed………………………………………………………(candidate) Date …………………………………………………. STATEMENT 1 This dissertation is the result of my own independent work/investigation, except where otherwise stated. Other sources are acknowledged explicit references. A bibliography is appended. Signed………………………………………………………(candidate) Date …………………………………………………. STATEMENT 2 I hereby give consent for my dissertation, if accepted, to be available for photocopying and for inter-library loan, and for the title and summary to be made available to outside organisations. Signed………………………………………………………(candidate) Date …………………………………………………. 2 Acknowledgements I would to take this opportunity to sincerely thank my supervisors, Elin Haf Gruffydd Jones and Dr Dafydd Sills-Jones for all their help and support during this research study. Thanks are also due to my colleagues in the Department of Theatre, Film and Television Studies, Aberystwyth University for their friendship during my time at Aberystwyth. I would also like to thank Prof Josephine Berndt and Dr Sheuo Gan, Kyoto Seiko University, Kyoto for their valuable insights during my visit in 2011. In addition, I would like to express my thanks to the Coleg Cenedlaethol for the scholarship and the opportunity to develop research skills in the Welsh language. Finally I would like to thank my wife Tomoko for her support, patience and tolerance over the last four years – diolch o’r galon Tomoko, ありがとう 智子. -

11Eyes Achannel Accel World Acchi Kocchi Ah! My Goddess Air Gear Air

11eyes AChannel Accel World Acchi Kocchi Ah! My Goddess Air Gear Air Master Amaenaideyo Angel Beats Angelic Layer Another Ao No Exorcist Appleseed XIII Aquarion Arakawa Under The Bridge Argento Soma Asobi no Iku yo Astarotte no Omocha Asu no Yoichi Asura Cryin' B Gata H Kei Baka to Test Bakemonogatari (and sequels) Baki the Grappler Bakugan Bamboo Blade Banner of Stars Basquash BASToF Syndrome Battle Girls: Time Paradox Beelzebub BenTo Betterman Big O Binbougami ga Black Blood Brothers Black Cat Black Lagoon Blassreiter Blood Lad Blood+ Bludgeoning Angel Dokurochan Blue Drop Bobobo Boku wa Tomodachi Sukunai Brave 10 Btooom Burst Angel Busou Renkin Busou Shinki C3 Campione Cardfight Vanguard Casshern Sins Cat Girl Nuku Nuku Chaos;Head Chobits Chrome Shelled Regios Chuunibyou demo Koi ga Shitai Clannad Claymore Code Geass Cowboy Bebop Coyote Ragtime Show Cuticle Tantei Inaba DFrag Dakara Boku wa, H ga Dekinai Dan Doh Dance in the Vampire Bund Danganronpa Danshi Koukousei no Nichijou Daphne in the Brilliant Blue Darker Than Black Date A Live Deadman Wonderland DearS Death Note Dennou Coil Denpa Onna to Seishun Otoko Densetsu no Yuusha no Densetsu Desert Punk Detroit Metal City Devil May Cry Devil Survivor 2 Diabolik Lovers Disgaea Dna2 Dokkoida Dog Days Dororon EnmaKun Meeramera Ebiten Eden of the East Elemental Gelade Elfen Lied Eureka 7 Eureka 7 AO Excel Saga Eyeshield 21 Fight Ippatsu! JuudenChan Fooly Cooly Fruits Basket Full Metal Alchemist Full Metal Panic Futari Milky Holmes GaRei Zero Gatchaman Crowds Genshiken Getbackers Ghost -

Ebook Download Japan the Culture

JAPAN THE CULTURE PDF, EPUB, EBOOK Bobbie Kalman | 32 pages | 30 Oct 2008 | Crabtree Publishing Co,Canada | 9780778796664 | English | New York, Canada Japan the Culture PDF Book Aesthetics The dual influences of East and West have helped construct a modern Japanese culture that offers familiar elements to the Westerner but that also contains a powerful and distinctive traditional cultural aesthetic. For most Japanese people, non-verbal communication is an important part of social interactions. Honshu is the largest of the four, followed in size by Hokkaido, Kyushu, and Shikoku. Non-Verbal Communication For most Japanese people, non-verbal communication is an important part of social interactions. Kimono come in a variety of colors, styles, and sizes. Oshibori Photo by Charles Haynes via Flickr Japanese restaurants often give customers a moist towel, known as oshibori , to clean their hands before eating. Main article: Japanese literature. May 22, at am - Reply. Meanwhile, a longer and deeper bow is more respectful and can signify a formal apology or sincere thanks. It consists of a great string of islands in a northeast-southwest arc that stretches for approximately 1, miles 2, km through the western North Pacific Ocean. Archived from the original PDF on 26 October Offer title:. These volcanic mountains provide Japan with numerous hot springs and spectacular scenery, but also put it at risk for devastating earthquakes and tsunami tidal waves. Drinking age laws are not as strictly enforced in Japan as they are in the U. For interpersonal relationships, the Japanese also avoid competition and confrontation and exercise self-control when working with others. -

Macdonald 4310.Pdf

Macdonald, Alastair Ewan (2016) Reimagining the vernacular story : textual roles, didacticism, and entertainment in Erpai. PhD Thesis. SOAS, University of London. http://eprints.soas.ac.uk/id/eprint/23804 Copyright © and Moral Rights for this PhD Thesis are retained by the author and/or other copyright owners. A copy can be downloaded for personal non‐commercial research or study, without prior permission or charge. This PhD Thesis cannot be reproduced or quoted extensively from without first obtaining permission in writing from the copyright holder/s. The content must not be changed in any way or sold commercially in any format or medium without the formal permission of the copyright holders. When referring to this PhD Thesis, full bibliographic details including the author, title, awarding institution and date of the PhD Thesis must be given e.g. AUTHOR (year of submission) "Full PhD Thesis title", name of the School or Department, PhD PhD Thesis, pagination. Reimagining the Vernacular Story: Textual Roles, Didacticism, and Entertainment in Erpai Alastair Ewan Macdonald 548934 Thesis submitted for the degree of PhD 2016 Department of China and Inner Asia SOAS, University of London 1 Declaration for SOAS PhD thesis I have read and understood regulation 17.9 of the Regulations for students of the SOAS, University of London concerning plagiarism. I undertake that all the material presented for examination is my own work and has not been written for me, in whole or in part, by any other person. I also undertake that any quotation or paraphrase from the published or unpublished work of another person has been duly acknowledged in the work which I present for examination. -

District to Replace Principal At

www.tooeletranscript.com THURSDAY TOOELETRANSCRIPT Students’ artwork hangs in elite show. See B1 BULLETIN March 16, 2006 SERVING TOOELE COUNTY SINCE 1894 VOL. 112 NO. 85 50 cents Forget Jazz, Miller is ready to race District to replace by Mark Watson STAFF WRITER principal at THS Eventually, Larry H. Miller may pursue other business ventures Westover let go, will finish out year in Tooele County, but his $75 by Jesse Fruhwirth million Miller Motorsports Park STAFF WRITER is just too important to him right Tooele High School will get a now to focus on much else. new leader next year. The super- Perhaps Miller needs some intendent of the Tooele County therapeutic relief from worrying School District has said Mike about the inconsistent play of Westover will finish out the cur- his Utah Jazz basketball play- rent year, but will not be back to ers. Perhaps deep down his big- serve as principal in the fall. gest thrill would be zipping along When pressed for comment, at 150 mph in one of his race school board vice president cars instead of sitting court side. Carol Jefferies confirmed the Perhaps his goal to open the rumors that had spread like wild- track next month is providing fire. She said Superintendent mixed emotions of questions still Michael Johnsen had decided he unanswered coupled with over- would not ask the second-year whelming excitement like that of Mike Westover principal to stay at the helm of a 3 year old on Christmas Eve. the district’s largest school. as “a great man, a great princi- Whatever the reason, In a later interview, Johnsen pal” but said he could not com- when Miller speaks about his himself said it was true. -

Echoing Spirits: a Composition for Shakuhachi, 21-String Koto, and Orchestra

ECHOING SPIRITS: A COMPOSITION FOR SHAKUHACHI, 21-STRING KOTO, AND ORCHESTRA A DISSERTATION SUBMITTED TO THE GRADUATE DIVISION OF THE UNIVERSITY OF HAWAI‘I AT MĀNOA IN PARTIAL FULFILLMENT OF THE REQUIREMENTS FOR THE DEGREE OF DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY IN MUSIC IN COMPOSITION MAY 2021 By William Watson Dissertation Committee: Chairperson, Donald Womack Thomas Osborne Takuma Itoh Kate McQuiston Mark Merlin TABLE OF CONTENTS • List of Tables……….…………………………………………………………………………iii • List of Examples.……….……….……….……….……….……….……….….….….….……iv • Note on Japanese Names and Terms…….……….……………………………………………vi • Introduction…………………………………………………………………………………….1 • Motivation Behind the Instrumentation………………………………………………………..2 • Precedents………….……….…………….……………………………………………………4 • Cross-cultural Compositional Strategies…………….…………………………………………7 • Extramusical Ideas………………………………………………………………………….12 • Formal Application of Jo Ha Kyū……………………………………………………….…15 • Analysis of Echoing Spirits………………….………………………………………………..16 • Form………………………………………………………………………………………..16 • Harmonic Language………………………………………………………………………..29 • Orchestration……………………………………………………………………………….40 • Conclusion…………………………………………………………………………………….45 • Bibliography…………………………………………………………………………………..46 "ii LIST OF TABLES Table 1. Dominant Jo Ha Kyū in Kodama……………………………………………………….18 Table 2. Subordinate Jo Ha Kyū within the Jo Phase of Kodama……………………………….18 Table 3: Subordinate Jo Ha Kyū within the Ha Phase of Kodama………………………………19 Table 4: Dominant Jo Ha Kyū in Kappa…………………………………………………………20 Table 5. Cyclic Structure of Kappa………………………………………………………………23