Carducci String Quartet

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Rehearing Beethoven Festival Program, Complete, November-December 2020

CONCERTS FROM THE LIBRARY OF CONGRESS 2020-2021 Friends of Music The Da Capo Fund in the Library of Congress The Anne Adlum Hull and William Remsen Strickland Fund in the Library of Congress (RE)HEARING BEETHOVEN FESTIVAL November 20 - December 17, 2020 The Library of Congress Virtual Events We are grateful to the thoughtful FRIENDS OF MUSIC donors who have made the (Re)Hearing Beethoven festival possible. Our warm thanks go to Allan Reiter and to two anonymous benefactors for their generous gifts supporting this project. The DA CAPO FUND, established by an anonymous donor in 1978, supports concerts, lectures, publications, seminars and other activities which enrich scholarly research in music using items from the collections of the Music Division. The Anne Adlum Hull and William Remsen Strickland Fund in the Library of Congress was created in 1992 by William Remsen Strickland, noted American conductor, for the promotion and advancement of American music through lectures, publications, commissions, concerts of chamber music, radio broadcasts, and recordings, Mr. Strickland taught at the Juilliard School of Music and served as music director of the Oratorio Society of New York, which he conducted at the inaugural concert to raise funds for saving Carnegie Hall. A friend of Mr. Strickland and a piano teacher, Ms. Hull studied at the Peabody Conservatory and was best known for her duets with Mary Howe. Interviews, Curator Talks, Lectures and More Resources Dig deeper into Beethoven's music by exploring our series of interviews, lectures, curator talks, finding guides and extra resources by visiting https://loc.gov/concerts/beethoven.html How to Watch Concerts from the Library of Congress Virtual Events 1) See each individual event page at loc.gov/concerts 2) Watch on the Library's YouTube channel: youtube.com/loc Some videos will only be accessible for a limited period of time. -

Boston Symphony Orchestra Concert Programs, Season 115, 1995-1996

BOSTON > V SYMPHONY ORCHESTRA ft SEIJIOZAWA MUSIC DIRECTOR 9 6 S E O N The security of a trust, Fidelity investment expertise. A CLumlc Composition Fidelity Just as a Beethoven score is at its best when performed by a world- Pergonal class symphony — so, too, should your trust assets be managed by Triittt a financial company recognized Serviced globally for its investment expertise. Fidelity Investments. That's why Fidelity now offers a % managed trust or personalized estment management account or your portfolio of $400,000 or more/ For more information, visit Fidelity Investor Center or call Fidelity Pergonal Trust Services at 1-800-854-2829. Visit a Fidelity Investor Center Near You: Boston - Back Bay • Boston - Financial District Braintree, MA • Burlington, MA Fidelity Investments' SERVICES OFFERED ONLY THROUGH AUTHORIZED TRUST COMPANIES. TRUST SERVICES VARY BY STATE. FIDELITY BROKERAGE SERVICES, INC., MEMBER NYSE, SIPC. Seiji Ozawa, Music Director Bernard Haitink, Principal Guest Conductor One Hundred and Fifteenth Season, 1995-96 Trustees of the Boston Symphony Orchestra, Inc. J. P. Barger, Chairman Nicholas T. Zervas, President Peter A. Brooke, Vice-Chairman Harvey Chet Krentzman, Vice-Chairman Mrs. Edith L. Dabney, Vice-Chairman William J. Poorvu, Vice-Chairman and Treasurer Mrs. John H. Fitzpatrick, Vice-Chairman Ray Stata, Vice-Chairman Harlan E. Anderson Nader F. Darehshori Edna S. Kalman Mrs. Robert B. Newman James F. Cleary Deborah B. Davis Allen Z. Kluchman Robert P. O'Block John E. Cogan, Jr. Nina L. Doggett George Krupp Peter C. Read Julian Cohen Avram J. Goldberg R. Willis Leith, Jr. Carol Scheifele-Holmes Chairman-elect William F. -

Quartet Dimensions

concert program ii: Quartet Dimensions JOHANN SEBASTIAN BACH (1685–1750)! July 21 WOLFGANG AMADEUS MOZART (1756–1791) Sunday, July 21, 6:00 p.m., The Center for Performing Arts Fugue in E-flat Major, BWV 876, and Fugue in d minor, BWV 877, from at Menlo-Atherton Das wohltemperierte Klavier; arr. String Quartets nos. 7 and 8, K. 405 JOSEPH HAYDN (1732–1809) PROGRAM OVERVIEW String Quartet in d minor, op. 76, no. 2, Quinten (1796) The string quartet medium, arguably the spinal column of the Allegro chamber music literature, did not exist in Bach’s lifetime. Yet Andante o più tosto allegretto Minuetto: Allegro ma non troppo even here, Bach’s legacy is inescapable. The fugues of his semi- Finale: Vivace assai nal The Well-Tempered Clavier inspired no less a genius than Danish String Quartet: Frederik Øland, Rune Tonsgaard Sørensen, violins; Asbjørn Nørgaard, viola; Mozart, who arranged a set of them for string quartet. The influ- Fredrik Schøyen Sjölin, cello ence of Bach’s architectural mastery permeates the ingenious DMITRY SHOSTAKOVICH (1906–1975) Quinten Quartet of Joseph Haydn, the father of the modern Piano Quintet in g minor, op. 57 (1940) string quartet, and even Dmitry Shostakovich’s Piano Quintet, Prelude composed nearly two hundred years after Bach’s death. The Fugue Scherzo centerpiece of Beethoven’s Opus 132—the Heiliger Dankgesang Intermezzo CONCERT PROGRAMSCONCERT eines Genesenen an die Gottheit (“A Convalescent’s Holy Song Finale PROGRAMSCONCERT of Thanksgiving to the Divinity”)—recalls another Bachian signa- Gilbert Kalish, piano; Danish String Quartet: Frederik Øland, Rune Tonsgaard Sørensen, violins; ture: the Baroque master’s sacred chorales. -

Franz Schubert Written and Narrated by Jeremy Siepmann with Tom George As Schubert

LIFE AND WORKS Franz Schubert Written and narrated by Jeremy Siepmann with Tom George as Schubert 8.558135–38 Life and Works: Franz Schubert Preface If music is ‘about’ anything, it’s about life. No other medium can so quickly or more comprehensively lay bare the very soul of those who make or compose it. Biographies confined to the limitations of text are therefore at a serious disadvantage when it comes to the lives of composers. Only by combining verbal language with the music itself can one hope to achieve a fully rounded portrait. In the present series, the words of composers and their contemporaries are brought to life by distinguished actors in a narrative liberally spiced with musical illustrations. Unlike the standard audio portrait, the music is not used here simply for purposes of illustration within a basically narrative context. Thus we often hear very substantial chunks, and in several cases whole movements, which may be felt by some to ‘interrupt’ the story; but as its title implies the series is not just about the lives of the great composers, it is also an exploration of their works. Dismemberment of these for ‘theatrical’ effect would thus be almost sacrilegious! Likewise, the booklet is more than a complementary appendage and may be read independently, with no loss of interest or connection. Jeremy Siepmann 8.558135–38 3 Life and Works: Franz Schubert © AKG Portrait of Franz Schubert, watercolour, by Wilhelm August Rieder 8.558135–38 Life and Works: Franz Schubert Franz Schubert(1797-1828) Contents Page Track Lists 6 Cast 11 1 Historical Background: The Nineteenth Century 16 2 Schubert in His Time 26 3 The Major Works and Their Significance 41 4 A Graded Listening Plan 68 5 Recommended Reading 76 6 Personalities 82 7 A Calendar of Schubert’s Life 98 8 Glossary 132 The full spoken text can be found on the CD-ROM part of the discs and at: www.naxos.com/lifeandworks/schubert/spokentext 8.558135–38 5 Life and Works: Franz Schubert 1 Piano Quintet in A major (‘Trout’), D. -

Quartetto Di Cremona Ludwig Van Beethoven String Quartet in C Minor, Op

BEETHOVEN COMPLETE STRING QUARTETS QUARTETTO DI CREMONA LUDWIG VAN Beethoven String Quartet in C minor, Op. 18, No. 4 24:05 1. Allegro ma non tanto 8:39 II. Andante scherzoso quasi Allegretto 7:01 III. Menuetto. Allegretto – Trio 3:37 IV. Allegro – Prestissimo 4:48 ‘Great Fugue’ in B flat major, Op. 133 15:13 Overtura. Allegro – Meno mosso e moderato – Allegro – Fuga – Meno mosso e moderato – Allegro molto e con brio – Meno mosso e moderato – Allegro molto e con brio String Quartet in F major, Op. 59, No. 1 39:13 I. Allegro 10:05 II. Allegretto vivace e sempre scherzando 8:45 III. Adagio molto e mesto 12:16 IV. Thème russe. Allegro 8:07 QUARtetto DI CREMONA Cristiano Gualco, Violine Paolo Andreoli, Violine Simone Gramaglia, Viola Giovanni Scaglione, Violoncello A quartet in C minor acquired in other genres. Only once Count Lobkowitz, one of Beethoven’s aristocratic During his first years in Vienna, Beethoven patrons, commissioned six string quartets noticeably held back from composing each from Haydn and Beethoven around string quartets and instead, apparently on the end of 1798 for the fee of 400 guil- account of studying this craft, resorted to ders, was there no turning back. Whilst copying quartets by Haydn and Mozart. Of the aged Haydn did not manage to ful- course he knew exactly that the much- fil his duty entirely, Beethoven feverishly quoted Bonn farewell by Count Wald- worked, alongside large-scale works such stein – “Sustained diligence will bring you as his First Symphony, the final version of Mozart’s spirit from Haydn’s hands” – did his Piano Concerto in C and his Septet not so much refer to the piano sonatas Op. -

Digital Booklet Porgy & Bess

71 TRACKS THE AMADEUS QUARtet ReCORDINGS VOL. I BEETHOVEN Berlin, 1950-1967 recording producer: Wolfgang Gottschalk (Op. 127) Hartung (Op. 59, 2) Hermann Reuschel (Op. 18, 2-5 / Op. 59, 1 / Op. 130-133 / Op. 135 / Op. 29) Salomon (Op. 18, 1+6 / Op. 59, 3 / Op. 95) recording engineer: Siegbert Bienert (Op. 18, 5 / Op. 130-133 / Op. 29) Peter Burkowitz (Op. 18, 6) THE Heinz Opitz (Op. 18, 2 / Op. 59, 1+2 / Op. 127 / Op. 135) Preuss (Op. 18, 1 / Op. 59, 3 / Op. 95) Alfred Steinke (Op. 18, 3+4) AMADEUS QUARtet ReCORDinGS Berlin, 1950-1967 Eine Aufnahme von RIAS Berlin (lizenziert durch Deutschlandradio) recording: P 1950 - 1967 Deutschlandradio research: Rüdiger Albrecht remastering: P 2013 Ludger Böckenhoff rights: audite claims all rights arising from copyright law and competition law in relation to research, compilation and re-mastering of the original audio tapes, VOL. I BEETHOVEN as well as the publication of this CD. Violations will be prosecuted. The historical publications at audite are based, without exception, on the original tapes from broadcasting archives. In general these are the original analogue tapes, MstASTER RELEASE which attain an astonishingly high quality, even measured by today’s standards, with their tape speed of up to 76 cm/sec. The remastering – professionally com- petent and sensitively applied – also uncovers previously hidden details of the interpretations. Thus, a sound of superior quality results. CD publications based 1 on private recordings from broadcasts cannot be compared with these. AMADEUS-QUARtett further reading: Daniel Snowman: The Amadeus Quartet. The Men and the Music, violin I Norbert Brainin Robson Books (London, 1981) violin II Siegmund Nissel Gerd Indorf: Beethovens Streichquartette, Rombach Verlag (Freiburg i. -

The Ninth Season Through Brahms CHAMBER MUSIC FESTIVAL and INSTITUTE July 22–August 13, 2011 David Finckel and Wu Han, Artistic Directors

The Ninth Season Through Brahms CHAMBER MUSIC FESTIVAL AND INSTITUTE July 22–August 13, 2011 David Finckel and Wu Han, Artistic Directors Music@Menlo Through Brahms the ninth season July 22–August 13, 2011 david finckel and wu han, artistic directors Contents 2 Season Dedication 3 A Message from the Artistic Directors 4 Welcome from the Executive Director 4 Board, Administration, and Mission Statement 5 Through Brahms Program Overview 6 Essay: “Johannes Brahms: The Great Romantic” by Calum MacDonald 8 Encounters I–IV 11 Concert Programs I–VI 30 String Quartet Programs 37 Carte Blanche Concerts I–IV 50 Chamber Music Institute 52 Prelude Performances 61 Koret Young Performers Concerts 64 Café Conversations 65 Master Classes 66 Open House 67 2011 Visual Artist: John Morra 68 Listening Room 69 Music@Menlo LIVE 70 2011–2012 Winter Series 72 Artist and Faculty Biographies 85 Internship Program 86 Glossary 88 Join Music@Menlo 92 Acknowledgments 95 Ticket and Performance Information 96 Calendar Cover artwork: Mertz No. 12, 2009, by John Morra. Inside (p. 67): Paintings by John Morra. Photograph of Johannes Brahms in his studio (p. 1): © The Art Archive/Museum der Stadt Wien/ Alfredo Dagli Orti. Photograph of the grave of Johannes Brahms in the Zentralfriedhof (central cemetery), Vienna, Austria (p. 5): © Chris Stock/Lebrecht Music and Arts. Photograph of Brahms (p. 7): Courtesy of Eugene Drucker in memory of Ernest Drucker. Da-Hong Seetoo (p. 69) and Ani Kavafian (p. 75): Christian Steiner. Paul Appleby (p. 72): Ken Howard. Carey Bell (p. 73): Steve Savage. Sasha Cooke (p. 74): Nick Granito. -

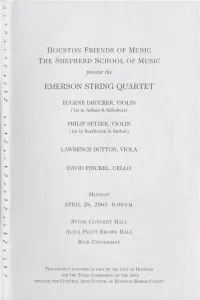

Emerson String Quartet

HOUSTON FRIENDS OF MUSIC THE SHEPHERD SCHOOL OF MUSIC present the EMERSON STRING QUARTET EUGENE DRUCKER, VIOLIN (1st in Aitken & Schubert) PHILIP SETZER, VIOLIN (1st in Beethoven & Barber) .. LAWRENCE DUTTON, VIOLA DAVID FINCKEL, CELLO MONDAY -,. APRIL 28, 2003 8:00 P.M. STUDE CONCERT HALL ALICE PRATT BROWN HALL RICE UNIVERSITY THIS PROJECT IS FUNDED IN PART BY THE CITY OF HOUSTON AND TIIE T EXAS COMMISSION ON THE ARTS THROUGH THE CULTURAL ARTS COUNCIL OF HOUSTON/HARRIS COUNTY. EMERSON STRING QUARTET -PROGRAM- LUDWIG van BEETHOVEN (1770-1827) Quartet in F Major, Op. 18, No. 1 (1798) Allegro con brio Adagio affettuoso ed appassionato Scherzo: Allegro molto Allegro HUGH AITKEN (b.1924) Laura Goes to India (1998) SAMUEL BARBER (1910-1981) A . Adagio for String Quartet, Op. 11 (1936) -INTERMISSION- FRANZ SCHUBERT (1797-1828) Quartet in D Minor, D. 810, "Death and the Maiden" (1824) Allegro Andante con moto Scherzo: Allegro molto Presto -.. The Emerson String Quartet appears by arrangement with IMC Artists and records exclusively for Deutsche Grammophon. www.emersonquartet.com LUDWIG van BEETHOVEN (1770-1827) Quartet in F Major, Op. 18, No. 1 (1798) ·.1 Beethoven wrote the Opus 18 Quartets during his first years in Vienna. He had arrived from Germany in 1792 by permission of the Elector of Bonn, shortly before his twenty-second birthday, in high spirits and carrying with him introductions to some of the most prominent members of music-loving Viennese nobility, who welcomed him into their substantial musical lives. At the end of his first four years in Vienna he had established himself as a pianist of major importance and a composer of the utmost promise; he had published, among other things, a set of three Piano Trios, Op.l, three Trios for Strings, Op. -

Takács Quartet

Sunday, December 7, 2014, 3pm Zellerbach Hall Takács Quartet Edward Dusinberre first violin Károly Schranz second violin Geraldine Walther viola András Fejér cello with Erika Eckert, viola PROGRAM Ludwig van B eethoven (1770–1827) String Quartet No. 13 in B-flat major, Op. 130 (1825–1826) Adagio ma non troppo — Allegro Presto Andante con moto ma non troppo Alla danza tedesca: Allegro assai Cavatina: Adagio molto espressivo Finale: Allegro INTERMISSION Wolfgang Amadeus Mozart (1756–1791) Quintet for Two Violins, Two Violas, and Cello in G minor, K. 516 (1787) Allegro Menuetto: Allegretto Adagio ma non troppo Adagio — Allegro Cal Performances’ – season is sponsored by Wells Fargo. PLAYBILL PROGRAM NOTES Ludwig van Beethoven (8==7-8>9=) but Beethoven, exhausted, was unable to begin String Quartet No. 8: in B-flat major, Galitzin’s quartets until May. “I am really im - Op. 8:7 patient to have a new quartet of yours,” badg - ered Galitzin. “Nevertheless, I beg you not to Composed in @FAC–@FAD. Premièred on mind and to be guided in this only by your in - March A@, @FAD, in Vienna, by the spiration and the disposition of your mind.” Schuppanzigh Quartet. The first of the quartets for Galitzin (E-flat major, Op. 127) was not completed until “I sit pondering and pondering. I have long February 1825; the second (A minor, Op. 132) known what I want to do, but I can’t get it was finished five months later; and the third down on paper. I feel I am on the threshold of (B-flat major, Op. -

The String Quartet

The Cambridge Companion to THE STRING QUARTET ............ edited by Robin Stowell published by the press syndicate of the university of cambridge The Pitt Building, Trumpington Street, Cambridge, United Kingdom cambridge university press The Edinburgh Building, Cambridge, CB2 2RU, UK 40 West 20th Street, New York, NY 10011–4211, USA 477 Williamstown Road, Port Melbourne, VIC 3207, Australia Ruiz de Alarcon´ 13, 28014 Madrid, Spain Dock House, The Waterfront, Cape Town 8001, South Africa http://www.cambridge.org C Cambridge University Press 2003 This book is in copyright. Subject to statutory exception and to the provisions of relevant collective licensing agreements, no reproduction of any part may take place without the written permission of Cambridge University Press. First published 2003 Printed in the United Kingdom at the University Press, Cambridge Typeface Minion 10.75/14 pt. SystemLATEX2ε [tb] A catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library Library of Congress Cataloguing in Publication data The Cambridge Companion to the string quartet / edited by Robin Stowell. p. cm. – (Cambridge companions to music) Includes bibliographical references and indexes. ISBN 0 521 80194 X (hardback) – ISBN 0 521 00042 4 (paperback) 1. String quartet. I. Stowell, Robin. II. Series. ML1160.C36 2003 785.7194 – dc21 2003043508 ISBN 0 521 80194 X hardback ISBN 0 521 00042 4 paperback Contents List of illustrations [page viii] Notes on the contributors [ix] Preface [xii] Acknowledgements [xiv] Note on pitch [xv] r Part I Social -

Cello Biennale 2018

programmaoverzicht Cellists Harald Austbø Quartet Naoko Sonoda Nicolas Altstaedt Jörg Brinkmann Trio Tineke Steenbrink Monique Bartels Kamancello Sven Arne Tepl Thu 18 Fri 19 Sat 20 Sun 21 Mon 22 Tue 23 Wed 24 Thu 25 Fri 26 Sat 27 Ashley Bathgate Maarten Vos Willem Vermandere 10.00-16.00 Grote Zaal 10.00-12.30 Grote Zaal 09.30 Grote Zaal 09.30 Grote Zaal 09.30 Grote Zaal 09.30 Grote Zaal 09.30 Grote Zaal 09.30 Grote Zaal Kristina Blaumane Maya Beiser Micha Wertheim First Round First Round (continued) Bach&Breakfast Bach&Breakfast Bach&Breakfast Bach&Breakfast Bach&Breakfast Bach&Breakfast Arnau Tomàs Matt Haimovitz Kian Soltani Jordi Savall Sietse-Jan Weijenberg Harriet Krijgh Lidy Blijdorp Mela Marie Spaemann Santiago Cañón NES Orchestras and Ensembles 10.15-12.30 10.15-12.30 10.30-12.45 Grote Zaal 10.15-12.30 10.15-12.30 10.15-12.30 10.15-12.30 10.30 and 12.00 Kleine Zaal Master class Master class Second Round Masterclass Masterclass Masterclass Masterclass Valencia Svante Henryson Accademia Nazionale di Santa Show for young children: Colin Carr (Bimhuis) Jordi Savall (Bimhuis) Jean-Guihen Queyras Nicolas Altstaedt (Bimhuis) Roel Dieltiens (Bimhuis) Matt Haimovitz (Bimhuis) Colin Carr Quartet Cecilia Spruce and Ebony Jakob Koranyi (Kleine Zaal) Giovanni Sollima (Kleine (Bimhuis) Michel Strauss (Kleine Zaal) Chu Yi-Bing (Kleine Zaal) Reinhard Latzko (Kleine Zaal) Zaal) Kian Soltani (Kleine Zaal) Hayoung Choi The Eric Longsworth Amsterdam Sinfonietta 11.00 Kleine Zaal Chu Yi-Bing Project Antwerp Symphony Orchestra Show for young children: -

Liner Notes by Patrick Castillo © 2019 Medium for His Deepest Musical Thoughts

Incredible Decades (2019) Disc 3. his father following its premiere). When the Opus 16 1–3 Quintet in E-flat Major for Winds and Piano, op. 16 Quintet was published, it appeared with an alternate (1796) version for piano quartet. LUDWIG VAN BEETHOVEN (1770–1827) The Quintet is cast in three movements. The Grave – Allegro, ma non troppo first movement begins with a slow introduction in the Andante cantabile French overture style, marked by stately dotted rhythms. Rondo: Allegro, ma non troppo The piano commences the Allegro proper with a melodious sixteen-bar theme, very much in the spirit of STEPHEN TAYLOR, oboe; TOMMASO LONQUICH, Mozart. Winds soon join in, enlivening the proceedings clarinet; PETER KOLKAY, bassoon; KEVIN RIVARD, horn; with a brilliant splash of color. As each voice engages in GILBERT KALISH, piano dialogue with one another, a magical quality comes to the fore—one, frankly, lost in the arrangement for 4–7 String Quartet in F Major, op. 135 (1826) strings. Each instrument’s timbre gives it a unique LUDWIG VAN BEETHOVEN identity, like distinct personalities in conversation: the Allegretto mellow clarinet, answered in turn by the jocular Vivace bassoon, the bellowing horn, the insistent oboe, with Lento assai, cantante e tranquillo the piano moderating all the while. Der Schwer gefasste Entschluss: Grave, A similar dynamic governs the lovely Andante ma non troppo tratto – Allegro cantabile. The tender melody is introduced, dolce, by the piano, then given luxurious voice by the full ensemble. ESCHER STRING QUARTET: ADAM BARNETT-HART, Two contrasting minor-key episodes feature expressive BRENDAN SPELTZ, violins; PIERRE LAPOINTE, viola; solo lines in each of the wind instruments: a mournful BROOK SPELTZ, cello tune sung by the oboe and later a solo turn by the horn—its brass timbre ideally suited to express a dignified melancholy.