The Practical Carver and Gilder's Guide and Picture Frame Maker's Companion

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

UPM CARGO HANDLING MANUAL – PAPER About This Manual

UPM CARGO HANDLING MANUAL – PAPER About this manual UPM Logistics aims to deliver UPM products to its The personnel must be skilled, trained and capable of Finnish Customs has granted UPM-Kymmene Oyj customers on time and in a sound condition. UPM also handling and transporting UPM products. Furthermore the an AEOF Certificate on the 11th of July 2011. AEOF aims to provide a healthy and safe working place for its personnel are to be instructed in environmental protection Certificate’s owner has a Customs Security Certificate for own employees and its partners’ employees. In order to and when relevant, qualified to transport and handle customs and logistics operations and is therefore justified achieve our goal that the supply chain earns reputation of hazardous goods. Training in applying the requirements for certain benefits in EU, for example simplified custom excellence in the eyes of the ultimate customer, UPM has contained in this manual will be provided by UPM in procedures and facilitations for customs declaration published the third version of Cargo Handling Manual. accordance with a separate plan. phase inspections. The manual contains the minimum compulsory The manual has been prepared in accordance with the Certificate’s owner needs to meet safety standards requirements for handling, transporting and warehousing best knowledge and understanding we have today. If regarding safety management, premises and personnel UPM products, and they are valid globally for all you feel there is a better, more secure, more efficient safety, logistics and production safety and also delivery parties (internal and external) in the logistics chain. way for handling, transporting or warehousing, we invite chain safety. -

Various Vendors, Per Attached CONTRACT PERIOD: BID OPENED: June 30, 2017 – June 29, 2018 May 25, 2017 BID REF

Madison County Purchasing Department 138 North Court Street PO Box 635 Wampsville, NY 13163 NOTICE OF CONTRACT AWARD AWARD: Various Vendors, per attached CONTRACT PERIOD: BID OPENED: June 30, 2017 – June 29, 2018 May 25, 2017 BID REF. #: 17.22 – Paper, RENEWAL: Envelopes & Office Supplies Two (2) additional, one (1) year periods INQUIRIES TO: DATE ISSUED: Laurie Winters, Purchasing Agent June 30, 2017 [email protected] 315-366-2247 This is only a synopsis of the contract. Complete contract documents/specifications are on file in the Purchasing Department. If you require additional information, you may call this office at (315) 366 - 2247 between 8:00 am and 4:00 pm. MUNIS Vendor Name & Address PHONE# & CONTACT VENDOR NO P: 315-472-1316 Dupli (Paper) Graphic F: 315-422-3637 4622 6761 Thompson Road Nathan Fleming Syracuse, NY 13211 [email protected] P: 800-765-4866 ext 247 Hummel’s Office Plus 2376 F: 800-673-3747 25 Canal Street Chelsea Hutton Mohawk, NY 13407 [email protected] P: 315-363-9527 Oneida Office Supply F: 315-280-6802 5487 226 Main Street Alison Baker or Stacy Jones Oneida, NY 13421 [email protected] Quill P: 800-634-4809 3458 PO Box 94080 Customer Service Palatine, IL 60094-4080 [email protected] The Tree House P: 800-595-6651 5893 PO Box 413 David Rizzo Norwood, MA 02062 [email protected] P: 888-926-2766 W B Mason Co Inc. F: 888-266-9082 4190 6018 Corporate Dr. Jenna Mosca East Syracuse, NY 13057 518-248-8523 [email protected] Bid 17.22 – 2017 Paper, Envelopes, & Office Supplies -

Dunnage Bags Securing Your Cargo

TRANSPORT PACKAGING SOLUTIONS Dunnage Bags Securing your cargo • Prevent transport damage • Clever loading Reduce Replace • Quick and easy to fit 3R • Reusable and recyclable Recycle • Up to todays standards Sustainable packaging is your contribution to the environment A cushion that protects cargo from shocks and the danger of collapsing during road, rail and sea transportation. An end to heavy, bulky wood that needs to be treated for pests and an end to other hard dunnage that is difficult to fit! A VARIETY OF SIZES AND STRENGHTS AVAILABLE. ASK US! • constructed of multiple layers of high-strength Kraft paper and an inner plastic lining that protects against loss of air pressure • the valve can be used several times, allowing for multiple use of the bag • easy to use and adapt to different sizes of space • a quick, convenient and cost-effective way to secure your cargo WITH WITHOUT Eltete Dunnage Bags will avoid any collapsing of the cargo. SPECIFICATIONS Size Various sizes Construction 1-4 ply Paper Clupak 100-120g/m2/layer Liner HDPE 170μ Working pressure Up to 0,35 bar Usage with loads Up to 20 tons Max VOID 45 cm Temperature range -30 to +70 °C Valve Fast filling multi-use valve Eltete TPM Ltd (Transport Packaging Materials) is a global carton board converter and an ISO- certified supplier of 100 % recyclable transport packaging materials. With own engineering Headquarters division we are able to react quickly to customer demands. Eltete TPM Ltd P.O.Box 94 With experience since 1974, we are experts on the needs of today´s market. -

Fillpak TT Paper Per Second

Ranpak Void Fill Systems... the Natural Choice ® Fast - output of up to 70 inches of FillPak TT paper per second Cut Mechanism Versatile - allows users to preset makes packing with paper length with the turn of a knob paper even easier for consistent void fill Compact- small, lightweight and easy to use for facilities with multiple Gives FillPak TT the Ability to Cut packing stations and Pre-define Paper Lengths - converter height and FillPak TT with cut mechanism converts Adaptable head angles are adjustable for ease fanfold kraft paper into a PaperStar™ and comfort while loading or packing configuration for fast and efficient void filling. In addition to adding a cut mechanism to Environmentally Friendly - 100% the FillPak TT, the upgrade also gives the biodegradable, recyclable and operator the ability to pre-set paper lengths renewable paper via an Electronic Delivery System (EDS) mode. The unit can be set up to dispense void fill material in lengths of 12 inches up to 10 feet. The TT with cut mechanism has the same small footprint as the regular FillPak TT and can be easily adapted to any packing environment or integrated into areas with limited space. The Paper Packaging Experts™ Specifications Converter Head (approximate measurements)* Paper Bundle Width 17" Basis Paper Width Length Weight Weight* Type (inches) (feet) (lbs.) Length 24" (lbs.) Depth 14" Fanfold 15 30 1,660 22 Box Weight 27 lbs. Fanfold 15 45 1,200 24 Power 100/115 VAC, 1 phase Box Feed Rate 70 inches/second *Also available in 100% recycled and 32-lb. white Cut Method Electric Motor Operating Modes Footswitch Paper Pallet Bundle Bundles Dimensions Weight Stand (approximate measurements)* Type per Pallet (inches) (lbs.) Table Stand Floor Stand 30 lb. -

100-Chef-Catalogue-MM-Site.Pdf

5 Aladín Ahumado y aromatización · Smoking & Flavouring 21 Tool Concepts 61 Noon Cocina y técnicas al vacío · Sous vide: cooking & techniques 83 Nitro & CO2 Nitrógeno Líquido · Liquid Nitrogen & Dry Ice 93 Stone Age 123 PorceLand 147 Glass concepts Más que vidrio · Beyond glass 207 Cátering Presentación ideal · Smart presentation 265 Plastic Design 277 Miniaturas Miniatures 293 Wood & Bamboo 307 Inox Creatividad inoxidable · Stainless Creativity 323 Moulds Dale forma! · Shape it! 10 years with... Ahumado y aromatización Smoking & Flavouring Paolo Casagrande Executive Chef Lasarte Restaurant, Barcelona Pere Castells Esque Pienso que 100%Chef es una impresa de una inquietud terrible, de las que todos queremos tener. En los años no ha sido un proveedor, ha sido amigo, nos ha Gastronomy Scientist, Researcher and dado ideas, nos ha acompañado y respaldado para que nuestro restaurante y Head of Gastronomic and Scientific nosotros en él, pudiésemos crecer y cocinar cómodamente y dar lo mejor de Research Department - Fundació Alícia, nosotros. Barcelona 100%Chef, nos ha enseñado constantemente lo importante que es reinventarse y creer en nuevos proyectos! Quien no ha pensado en estos años… por qué no La revolución culinaria se ha convertido realmente radical en el siglo XXI, y ha se me ha ocurrido a mi¿? O, wow... esto es la bomba... cada vez que ha salido sido aquí donde ha jugado un papel preponderante en la investigación y la algo nuevo al mercado. Pues sí... esto es 100%Chef!!!” innovación culinaria, logrando consolidar su proyección internacional. Siempre I think that 100%Chef is a company with a formidable restlessness, the one that se habla de los grandes chefs, pero empresas como 100%Chef han contribuido we all want to have. -

Fillpak TT Per Second Void Fill on Demand Where and When You Need It Compact- Small, Lightweight and Designed for Multiple Packing Stations

Ranpak Void Fill Systems... the Natural Choice ® Fast - output of 60 inches of paper FillPak TT per second void fill on demand where and when you need it Compact- small, lightweight and designed for multiple packing stations Versatile - easily configured for floor High Speed and Cost-Effective or table operations Void Fill Adaptable - battery option allows for FillPak TT converts 15" single-ply, fanfold operation without electrical outlets kraft paper into a PaperStar™ configuration for fast and efficient void fill material to Environmentally Friendly - 100% protect products in shipment. biodegradable, recyclable and renewable paper Place a FillPak TT at multiple packing stations to maintain packing efficiency while minimizing material cost and usage. FillPak TT is easily operated by a foot pedal and dispenses void fill material directly into a box, allowing for maximum throughput. The converter height and head angle is adjustable and easy to rotate for optimal comfort while packing and loading. In addition, the small footprint allows it to easily fit into areas with limited space. Protection is in our nature™ Specifications Converter Head (approximate measurements)* Paper Bundle Width 17" Basis Paper Width Length Weight Weight Type (inches) (feet) (lbs.) Length 21" (lbs.) Depth 13" Fanfold 15 30* 1,660 22 Box Weight 17 lbs. Fanfold 15 45 1,200 24 Power 100/115 VAC, 1 phase Box Feed Rate 60 inches/second *30-lb. also available in 100% recycled and white. Cut Method Manual Tear Operating Modes Footswitch Paper Pallet Bundle Bundles Dimensions Weight Stand (approximate measurements)* Type per Pallet (inches) (lbs.) Table Stand Floor Stand 30 lb. -

05. at a Glance of KOREA PACK 2016

2016 SHOW REPORT www.KOREAPACK.org 01. Gist of Exhibition Title The 20th Korea Int’l Packaging Exhibition (KOREA PACK 2016) Period April 26(Tue.) – 29(Fri.), 2016 (4 Days) Frequency Annual Opening hours 10:00-17:00 (Last day: 10:00-16:00) Venue Hall 1~5, KINTEX 1 No. of Exhibitor 1300 Exhibitors, 3500 Booths (including concurrent events’) No. of Visitor 62,457 Visitors (Overseas: 2,879) (including concurrent events’) Organized by Korea Packaging Machinery Association (KPMA), Kyungyon Exhibition Corp The Monthly Packaging Exhibits Packaging Machinery Packaging Materials & Containers Package Printing Machines Packaging Inspection Equipment Packaging Processing Machinery & Equipment Package Design, Services, Food Processing Machinery Logistic System & Equipment Website www.koreapack.org Concurrent Events 》》 KINTEX 1 Hall 1 ▶ The 6th Korea Int’l Materials Handling & Logistics Exhibition (KOREA MAT 2016) Hall 2~5 ▶ The 20th Korea Int’l Packaging Exhibition (KOREA PACK 2016) Hall 3 ▶ The 11th Cosmetic∙Pharmaceutical Machinery & Equipment Exhibition (COPHEX 2016) Hall 5 ▶ KOREA PACK 2016 (FOOD PROCESSING) 》》 KINTEX 2 Hall 9 ▶ The 8th Korea Int’l Chemical Processing & Equipment Exhibition (KOREA CHEM 2016) Hall 9 ▶ The 6th Korea Int’l Pharmaceutical Exhibition (KOREA PHARM 2016) Hall 9 ▶ Korea Int’l Cosmetic Ingredient & Technology Exhibition (COSMETIC INSIDE KOREA 2016) Hall 10 ▶ The 10th Korea Int’l Laboratory & Analytical Equipment Exhibition (KOREA LAB 2016) 2016 SHOW REPORT www.KOREAPACK.org 02. 2016 Show Report Exhibitor & Visitor -

Systainer® T-LOC I

PACKING | ORGANISING | PRESENTING | TRANSPORTING THE SYSTEMATIC PROFESSIONAL Main Catalogue TANOS Main Catalogue Unique. Patented. Unbeatable. Stackable. Linkable. The systainer® is not just a case, it's a system. 2 / 3 CONTENTS TANOS OUR systainer® The original Page 4 - 5 Everything is based around the systainer® Page 6 - 7 In use everywhere Page 8 - 9 More than just a case Page 10 - 11 All-round service Page 12 - 13 Product variety Page 14 - 15 systainer® THE RIGHT ANSWER One-handed? – T-Loc! Page 16 - 17 Proven? – Classic! Page 18 - 19 Packing? – Safe! Page 20 - 21 Tidy? – Everything in its place! Page 22 - 23 Presentation? – In the limelight! Page 24 - 25 Transport? – Effortless! Page 26 - 27 systainer® PRODUCT RANGE Our product range Page 28 - 67 TANOS Our systainer® systainer® T-LOC A flick of the wrist suffices! That's just how simple the systainer® of the 2nd generation works. Stack individual systainer® systematically one on top of the other and lock with a flick of the wrist – this gives you a linked systainer® tower which holds everything from the smallest to the biggest part ready for you in a clear arrangement to save space and time and can be added to or divided up as you like. Our systainer® T-Loc combines innovative technology with functional, attractive design in perfection. systainer® CLASSIC Proven top class quality! Our systainer® CLASSIC has been accompanying millions of satisfied cus- tomers through their daily routine for ages. At work or at home, for your hobby or leisure time – the so- phisticated mechanics of the systainer® CLASSIC products guarantees reliability and almost infinite application possibilities. -

Pallet Literature Sheet

STAY -FLAT ™ ALUMINUM AND WOODEN PALLET S F OR ALL TEXTILE EQUI P MENT INCLUDING PALLET RUBBER , PALLET BRACKETS , TAPE AND PALLET ADHESIVES OEM Replacement Parts & Remanufacturing Services for the Screen Printer A Division of The A.W.T. World Trade Group Chicago, IL 60641 USA www.gpiparts.com 2 YOUR COMPLETE MANUFACTURING SOURCE FOR HIGH -QUALIT Y PALLETS FOR ALL T Y PES OF APPLICATIONS AND E Q UIPMENT G.P.I.’s Stay-Flat™ high performance pallets are Stay Flat Aluminum Pallets are manufac- manufactured in aluminum or wood. They are tured in standard designs to fit: designed to remain as smooth and flat as pos- sible when exposed to high heat and moisture in M&R Advance- A.W.T. high-volume production shops. Hundreds of standard * Formula American Print-Tex and specialty sizes are manufactured by G.P.I. in a Challenger Centurian Econo-Tex choice of configurations to meet the needs of any tex- Gauntlet Multiprinter tile screen printer. Blue Max Rototex Atlas • Wood, solid aluminum or aluminum honeycomb and more • With or without heat-resistant rubber covering • Hundreds of shapes and sizes for all applications Precision* MHM* Tuf* • Most bracket configurations available Ultimate SP Series Olympian Versa-Oval Javelin Stay-Flat™ Textile Pallets are G.P.I.’s exclusive Premier design. We have traveled worldwide to research the many types of textile pallets manufactured. Our techni- OPP Clip On TAS* Harco* cians developed these top-of-the-line pallets based on OPM Clip On 200 Series Anatol* international knowledge of printing equipment and pal- 300 Series Lawson* let applications. -

Detailed Project Reports the Detailed Project Reports Cover

Detailed Project Reports The detailed project reports cover all the aspects of business, from analyzing the market, confirming availability of various necessities such as plant & machinery, raw materials to forecasting the financial requirements. The scope of the report includes assessing market potential, negotiating with collaborators, investment decision making, corporate diversification planning etc. in a very planned manner by formulating detailed manufacturing techniques and forecasting financial aspects by estimating the cost of raw material, formulating the cash flow statement, projecting the balance sheet etc. The DPR is prepared by highly qualified and experienced consultants and the market research and analysis are supported by a panel of experts and computerized data bank. Each Detailed Project Report Contains • Beginning: Project Introduction, Brief History of the Product, Properties, BIS (Bureau of Indian Standard) Specifications & Requirements, Uses & Applications. • Manufacturing Techniques: Formulae Detailed Process of Manufacture, Flow Sheet Diagram. • Market Survey: Present Market Position, Expected Future Demand, Statistics of Imports & Exports, Export Prospect, Names and Addresses of Existing Units (Present Manufactures). • Personnel Requirements: Requirement of Staff & Labor, Personnel Management, Skilled & Unskilled Labor. • Plant & Machinery: List of Plant & Machineries, Miscellaneous Items and Accessories, Instruments, Laboratory Equipment's and Accessories, Plant Location, Electrification, Electric Load and Water, -

Packaging That Will Grow Your Business

APPLICATIONS SPECIFICATIONS Whether you need stronger pads or Pads can be used to cushion both pads with more flexibility, PadPak light and heavy items, from glass Guardian can produce both. That vases through to electrical motors, makes it well-suited to almost any using a single pad to cushion sides packaging environment, from and corners or rolling up packaging automotive to e-commerce. into a coil. Converter Floorstand Tablestand Dimensions (w x d x h) 61 x 110 x 163 cm 61 x 87 x 139 cm Weight 93 kg 89 kg Power 1050 W 1050 W Voltage 100-240 VAC 100-240 VAC Paper packs 90 Ecoline 90 Virgin 70/70 Rec/Vir 70/75 Rec/Eco Length 300 m 300 m 180 m 180 m Width 38 cm 38 cm 38 cm 38 cm Paper basis weight 90 g 90 g 70/70 g 70/75 g Pack weight 21 kg 21 kg 20 kg 21 kg Paper pallet 90 Ecoline 90 Virgin 70/70 Rec/Vir 70/75 Rec/Eco Packaging Pallet load 24 packs 24 packs 24 packs 24 packs Pallet dimensions (w x d x h) 120 x 80 x 110 cm 120 x 80 x 110 cm 120 x 80 x 110 cm 120 x 80 x 110 cm that will grow Pallet weight 514 kg 514 kg 490 kg 514 kg PPGD-FOL2005-EN your business ranpak.com Reach us at: +31 88 255 1111 | [email protected] PadPak® Guardian™ is YOUR BENEFITS COMPACTNESS Excellent product protection Sustainable materials Sustainable, cost-effective, and Over the years Ranpak has PadPak Guardian simplifies Converters can be moved easily Reliable protection for your Ranpak is leading the way for versatile packaging helps your developed converters of different everything, combining multiple by operators when required, and the sustainable, compact, products is a must. -

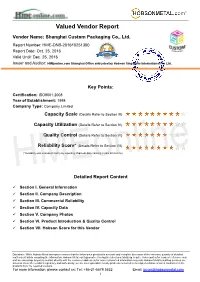

Valued Vendor Report

Valued Vendor Report Vendor Name: Shanghai Custom Packaging Co., Ltd. Report Number: HME-DNB-201610251300 Report Date: Oct. 25, 2016 Valid Until: Dec. 25, 2016 Issuer and Auditor: HMEonline.com Shanghai Office entrusted by Hobson Singapore International Pte Ltd. Key Points: Certification: ISO9001:2008 Year of Establishment: 1998 Company Type: Company Limited Capacity Scale (Details Refer to Section III) Capacity Utilization (Details Refer to Section IV) Quality Control (Details Refer to Section VI) Reliability Score* (Details Refer to Section VII) (*Reliability was evaluated mainly by exporting shipment data tracking in past 60 months) Detailed Report Content Section I. General Information Section II. Company Description Section III. Commercial Reliability Section IV. Capacity Data Section V. Company Photos Section VI. Product Introduction & Quality Control Section VII. Hobson Score for this Vendor Disclaimer: While Hobson Metal attempts to ensure that the information provided is accurate and complete by reason of the immense quantity of detailed matter dealt within compiling the information, Hobson Metal can't guarantee it being the latest and totally up to date. This report is for readers’ reference only and we encourage buyers to contact directly with the vendor or address us for more customized information requests. Hobson Metal’s auditing services are aimed to check the vendor’s legitimacy and authenticity; we are not responsible for any problems occurred in the implementation of sales contract or in the products from the