The Ethics of Meaning

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Anthropological Study of Yakama Tribe

1 Anthropological Study of Yakama Tribe: Traditional Resource Harvest Sites West of the Crest of the Cascades Mountains in Washington State and below the Cascades of the Columbia River Eugene Hunn Department of Anthropology Box 353100 University of Washington Seattle, WA 98195-3100 [email protected] for State of Washington Department of Fish and Wildlife WDFW contract # 38030449 preliminary draft October 11, 2003 2 Table of Contents Acknowledgements 4 Executive Summary 5 Map 1 5f 1. Goals and scope of this report 6 2. Defining the relevant Indian groups 7 2.1. How Sahaptin names for Indian groups are formed 7 2.2. The Yakama Nation 8 Table 1: Yakama signatory tribes and bands 8 Table 2: Yakama headmen and chiefs 8-9 2.3. Who are the ―Klickitat‖? 10 2.4. Who are the ―Cascade Indians‖? 11 2.5. Who are the ―Cowlitz‖/Taitnapam? 11 2.6. The Plateau/Northwest Coast cultural divide: Treaty lines versus cultural 12 divides 2.6.1. The Handbook of North American Indians: Northwest Coast versus 13 Plateau 2.7. Conclusions 14 3. Historical questions 15 3.1. A brief summary of early Euroamerican influences in the region 15 3.2. How did Sahaptin-speakers end up west of the Cascade crest? 17 Map 2 18f 3.3. James Teit‘s hypothesis 18 3.4. Melville Jacobs‘s counter argument 19 4. The Taitnapam 21 4.1. Taitnapam sources 21 4.2. Taitnapam affiliations 22 4.3. Taitnapam territory 23 4.3.1. Jim Yoke and Lewy Costima on Taitnapam territory 24 4.4. -

Microfilmed 1994 Information to Users

U-M-I MICROFILMED 1994 INFORMATION TO USERS This manuscript has been reproduced from the microfilm master. UMI films the text directly from the original or copy submitted. Thus, some thesis and dissertation copies are in typewriter face, while others may be from any type of computer printer. The quality of this reproduction is dependent upon the quality of the copy submitted. Broken or indistinct print, colored or poor quality illustrations and photographs, print bleed through, substandard margins, and improper alignment can adversely affect reproduction. In the unlikely, event that the author did not send UMI a complete manuscript and there are missing pages, these will be noted. Also, if unauthorized copyright material had to be removed, a note will indicate the deletion. Oversize materials (e.g., maps, drawings, charts) are reproduced by sectioning the original, beginning at the upper left-hand corner and continuing from left to right in equal sections with small overlaps. Each original is also photographed in one exposure and is included in reduced form at the back of the book. Photographs included in the original manuscript have been reproduced xerographically in this copy. Higher quality 6" x 9” black and white photographic prints are available for any photographs or illustrations appearing in this copy for an additional charge. Contact UMI directly to order. UMI University Microfilms international A Bell & Howell Information Com pany 300 North Zeeb Road, Ann Arbor. Ml 48106-1346 USA 313/761-4700 800/521-0600 Order Number 0411800 lnnokentij Annensky’s “The Cypress Chest”: Contexts, structures and themes Armstrong, Todd Patrick, Ph.D. -

2016 Film Writings by Roderick Heath @ Ferdy on Films

2016 Film Writings by Roderick Heath @ Ferdy On Films © Text by Roderick Heath. All rights reserved. Contents: Page Man in the Wilderness (1971) / The Revenant (2015) 2 Titanic (1997) 12 Blowup (1966) 24 The Big Trail (1930) 36 The Rocky Horror Picture Show (1975) 49 Dead Presidents (1995) 60 Knight of Cups (2015) 68 Yellow Submarine (1968) 77 Point Blank (1967) 88 Think Fast, Mr. Moto / Thank You, Mr. Moto (1937) 98 Push (2009) 112 Hercules in the Centre of the Earth (Ercole al Centro della Terra, 1961) 122 Airport (1970) / Airport 1975 (1974) / Airport ’77 (1977) / The Concorde… Airport ’79 (1979) 130 High-Rise (2015) 143 Jurassic Park (1993) 153 The Time Machine (1960) 163 Zardoz (1974) 174 The War of the Worlds (1953) 184 A Trip to the Moon (Voyage dans la lune, 1902) 201 2046 (2004) 216 Bride of Frankenstein (1935) 226 Alien (1979) 241 Solaris (Solyaris, 1972) 252 Metropolis (1926) 263 Fährmann Maria (1936) / Strangler of the Swamp (1946) 281 Viy (1967) 296 Night of the Living Dead (1968) 306 Fantastic Beasts and Where to Find Them (2016) 320 Neruda / Jackie (2016) 328 Rogue One (2016) 339 Man in the Wilderness (1971) / The Revenant (2015) Directors: Richard C. Sarafian / Alejandro Gonzalez Iñárritu By Roderick Heath The story of Hugh Glass contains the essence of American frontier mythology—the cruelty of nature met with the indomitable grit and resolve of the frontiersman. It‘s the sort of story breathlessly reported in pulp novellas and pseudohistories, and more recently, of course, movies. Glass, born in Pennsylvania in 1780, found his place in legend as a member of a fur-trading expedition led by General William Henry Ashley, setting out in 1822 with a force of about a hundred men, including other figures that would become vital in pioneering annals, like Jim Bridger, Jedediah Smith, and John Fitzgerald. -

Inventing Television: Transnational Networks of Co-Operation and Rivalry, 1870-1936

Inventing Television: Transnational Networks of Co-operation and Rivalry, 1870-1936 A thesis submitted to the University of Manchester for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy In the faculty of Life Sciences 2011 Paul Marshall Table of contents List of figures .............................................................................................................. 7 Chapter 2 .............................................................................................................. 7 Chapter 3 .............................................................................................................. 7 Chapter 4 .............................................................................................................. 8 Chapter 5 .............................................................................................................. 8 Chapter 6 .............................................................................................................. 9 List of tables ................................................................................................................ 9 Chapter 1 .............................................................................................................. 9 Chapter 2 .............................................................................................................. 9 Chapter 6 .............................................................................................................. 9 Abstract .................................................................................................................... -

A Hundred Years Since Sholem Aleichem's Demise Ephraim Nissan

Nissan, “Post Script: A Hundred Years Since Sholem Aleichem’s Demise” | 116 Post Script: A Hundred Years since Sholem Aleichem’s Demise Ephraim Nissan London The year 2016 was the centennial year of the death of the Yiddish greatest humorist. Figure 1. Sholem Aleichem.1 The Yiddish writer Sholem Aleichem (1859–1916, by his Russian or Ukrainian name in real life, Solomon Naumovich Rabinovich or Sholom Nokhumovich Rabinovich) is easily the best-known Jewish humorist whose characters are Jewish, and the setting of whose works is mostly in a Jewish community. “The musical Fiddler on the Roof, based on his stories about Tevye the Dairyman, was the first commercially successful English-language stage production about Jewish life in Eastern Europe”. “Sholem Aleichem’s first venture into writing was an alphabetic glossary of the epithets used by his stepmother”: these Yiddish 1 http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/File:Sholem_Aleichem.jpg International Studies in Humour, 6(1), 2017 116 Nissan, “Post Script: A Hundred Years Since Sholem Aleichem’s Demise” | 117 epithets are colourful, and afforded by the sociolinguistics of the language. “Early critics focused on the cheerfulness of the characters, interpreted as a way of coping with adversity. Later critics saw a tragic side in his writing”.2 “When Twain heard of the writer called ‘the Jewish Mark Twain’, he replied ‘please tell him that I am the American Sholem Aleichem’”. Sholem Aleichem’s “funeral was one of the largest in New York City history, with an estimated 100,000 mourners”. There exists a university named after Sholem Aleichem, in Siberia near China’s border;3 moreover, on the planet Mercury there is a crater named Sholem Aleichem, after the Yiddish writer.4 Lis (1988) is Sholem Aleichem’s “life in pictures”. -

Elizabeth Price: a Restoration the Contemporary Art Society Award

Ashmolean Museum of Art and Archaeology University of Oxford press release Beaumont Street Oxford OX1 2PH www.ashmolean.org 14 March 2016, for immediate release: Elizabeth Price: A RESTORATION The Contemporary Art Society Award 18 March–15 May 2016 Elizabeth Price, winner of the 2013 Contemporary Art Society Award, has created a new work in response to the collections and archives of the Ashmolean and Pitt Rivers museums, in partnership with the Ruskin School of Art, Oxford, where Price teaches. The new commission is a fifteen-minute, two-screen digital video which employs the museums’ photographic and graphic archives. It is a fiction, set to melody and percussion, which is narrated by a ‘chorus’ of museum administrators. The film opens with the records of Arthur Evans’s excavation of the Cretan city of Knossos. The administrators use Evans’s extraordinary documents and photographs to figuratively reconstruct the Knossos Labyrinth within the museum’s computer server. They then imagine its involuted space as a virtual chamber through which a wide range of artefacts from the two museums digitally flow, clatter and cascade. Elizabeth Price at the Contemporary Art Society Awards, 2013 Elizabeth Price says: ‘It has been a great pleasure and privilege to work with the museums, to have such a unique opportunity to delve into their archives and draw upon the knowledge and expertise of their staff. In my film I have tried to reflect upon the objects that the two museums hold and exhibit, through the history of their repeated depiction in photographs, prints and drawings. In this history of images and interpretations we see the objects change – and this is the basis for the story I have imagined.’ Turner Prize winner, Elizabeth Price, is an artist who uses images, text and music to explore archives and collections. -

Exemplar Texts for Grades

COMMON CORE STATE STANDARDS FOR English Language Arts & Literacy in History/Social Studies, Science, and Technical Subjects _____ Appendix B: Text Exemplars and Sample Performance Tasks OREGON COMMON CORE STATE STANDARDS FOR English Language Arts & Literacy in History/Social Studies, Science, and Technical Subjects Exemplars of Reading Text Complexity, Quality, and Range & Sample Performance Tasks Related to Core Standards Selecting Text Exemplars The following text samples primarily serve to exemplify the level of complexity and quality that the Standards require all students in a given grade band to engage with. Additionally, they are suggestive of the breadth of texts that students should encounter in the text types required by the Standards. The choices should serve as useful guideposts in helping educators select texts of similar complexity, quality, and range for their own classrooms. They expressly do not represent a partial or complete reading list. The process of text selection was guided by the following criteria: Complexity. Appendix A describes in detail a three-part model of measuring text complexity based on qualitative and quantitative indices of inherent text difficulty balanced with educators’ professional judgment in matching readers and texts in light of particular tasks. In selecting texts to serve as exemplars, the work group began by soliciting contributions from teachers, educational leaders, and researchers who have experience working with students in the grades for which the texts have been selected. These contributors were asked to recommend texts that they or their colleagues have used successfully with students in a given grade band. The work group made final selections based in part on whether qualitative and quantitative measures indicated that the recommended texts were of sufficient complexity for the grade band. -

Explaining the Self: a Contextual Study of Saul Bellow, Philip Roth and Joseph Heller

EXPLAINING THE SELF: A CONTEXTUAL STUDY OF SAUL BELLOW, PHILIP ROTH AND JOSEPH HELLER. DAVID LEON GIDEON BRAUNER PhD THESIS UNIVERSITY COLLEGE LONDON ProQuest Number: 10044352 All rights reserved INFORMATION TO ALL USERS The quality of this reproduction is dependent upon the quality of the copy submitted. In the unlikely event that the author did not send a complete manuscript and there are missing pages, these will be noted. Also, if material had to be removed, a note will indicate the deletion. uest. ProQuest 10044352 Published by ProQuest LLC(2016). Copyright of the Dissertation is held by the Author. All rights reserved. This work is protected against unauthorized copying under Title 17, United States Code. Microform Edition © ProQuest LLC. ProQuest LLC 789 East Eisenhower Parkway P.O. Box 1346 Ann Arbor, Ml 48106-1346 ABSTRACT I offer an exploration of the work of these three contemporary novelists, focusing on the phenomenon of self-explanation - both in the sense of justifying oneself, and o f seeking to define the nature o f selfhood. I identify three roles in which (and against which) these self-explanations take place; as writers o f comedy, as Jewish writers, and as American writers. Although these roles overlap, I treat them as distinct for the purposes o f structural clarity and contextualise them by locating them in related literary and cultural traditions. I am particularly concerned with the ambivalent attitudes that these writers display towards these roles; with the tensions between - and within - their theory and practice. The thesis is divided into three chapters, framed by an introduction and conclusion. -

John Ashbery 125 Part Twelve the Voyages of John Matthias 133

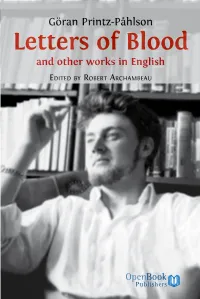

Göran Printz-Påhlson Letters of Blood and other works in English EDITED BY ROBERT ARCHAMBEAU To access digital resources including: blog posts videos online appendices and to purchase copies of this book in: hardback paperback ebook editions Go to: https://www.openbookpublishers.com/product/86 Open Book Publishers is a non-profit independent initiative. We rely on sales and donations to continue publishing high-quality academic works. Letters of Blood and other works in English Göran Printz-Påhlson Edited by Robert Archambeau https://www.openbookpublishers.com © 2011 Robert Archambeau; Foreword © 2011 Elinor Shaffer; ‘The Overall Wandering of Mirroring Mind’: Some Notes on Göran Printz-Påhlson © 2011 Lars-Håkan Svensson; Göran Printz-Påhlson’s original texts © 2011 Ulla Printz-Påhlson. Version 1.2. Minor edits made, May 2016. Some rights are reserved. This book is made available under the Creative Commons Attribution- Non-Commercial-No Derivative Works 2.0 UK: England & Wales License. This license allows for copying any part of the work for personal and non-commercial use, providing author attribution is clearly stated. Attribution should include the following information: Göran Printz-Påhlson, Robert Archambeau (ed.), Letters of Blood. Cambridge, UK: Open Book Publishers, 2011. http://dx.doi.org/10.11647/OBP.0017 In order to access detailed and updated information on the license, please visit https://www. openbookpublishers.com/product/86#copyright Further details about CC BY-NC-ND licenses are available at https://creativecommons.org/ licenses/by-nc-nd/2.0/ All the external links were active on 02/5/2016 unless otherwise stated and have been archived via the Internet Archive Wayback Machine at https://archive.org/web Digital material and resources associated with this volume can be found at https://www. -

Ibrahim El-Salahi a Sudanese Artist in Oxford Ibrahim El-Salahi a Sudanese Artist in Oxford

ibrahim el-salahi a sudanese artist in oxford Ibrahim El-Salahi A Sudanese Artist in Oxford Lena Fritsch Contents ibrahim el-salahi Director’s Foreword 7 a sudanese artist in oxford Introduction 9 Copyright © Ashmolean Museum, University of Oxford, 2018 From Omdurman to Oxford 13 Lena Fritsch has asserted her moral right to be identified as the author of this work. In Conversation with Ibrahim El-Salahi 49 British Library Cataloguing in Publications Data Ancient Sudan in the Ashmolean Museum 59 Liam McNamara A catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library Ibrahim El-Salahi and the Sudanese Community in Oxford 63 EAN 13: 978-1-910807-23-1 Nazar Eltahir All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic or mechanical, including Chronology 64 photocopy, recording or any storage and retrieval system, without Federica Gigante the prior permission in writing of the publisher. Curator’s Acknowledgements 72 Catalogue designed by Stephen Hebron Printed and bound in Belgium by Albe de Coker For further details of Ashmolean titles please visit: www.ashmolean.org/shop Director’s Foreword Celebrated as a pioneer of African and Arab Modernism, Ibrahim El- Salahi (b.1930) is one of the most influential figures in Sudanese art today. His paintings and drawings combine inventive forms of calligraphy, African abstraction and a profound knowledge of European art history in a unique language. Widely exhibited and collected internationally, the artist has lived and worked in Oxford since 1998. Te Ashmolean Museum is proud to present the first solo exhibition of Ibrahim El-Salahi’s works in Oxford. -

Full Text In

FRIENDS OF THE SOVIET UNION India’s Solidarity with the USSR during the Second World War in 1941-1945 L. V. MITROKHIN INDO RUSSIAN CHAMBER OF COMMERCE AND INDUSTRIES 74, Russian Cultural Centre, Kasthuri Ranga Road, Alwarpet, Chennai – 600 018. DEDICATED TO MY WIFE SOUSANNA AND MY DAUGHTERS OLGA AND ANNA 2 CONTENTS INTRODUCTION 1 Anti-Fascist Tradition in India 6 Indian Support to Anti-Fascist Forces: FSU Movement Makes Headway 14 THE YEAR 1941 25 German Invasion of the Soviet Union: Condemnation in India 27 The First All India FSU Meet: Fighting Solidarity with the USSR 37 Unanimous Admiration for Russian Resistance 50 THE YEAR 1942 63 Consolidation of Anti-Fascist Forces in India: Left Democratic Sections and the Slogan of People’s War 65 Conference of the Friends of the Soviet Union of United Provinces, Lucknow 80 Establishment of Direct Contacts with the USSR: The Story of a Goodwill Mission 86 Day of Solidarity 91 Solidarity with the USSR of the Indian Political Detenus Imprisoned by British Colonial Administration 9 3 The Heroic Struggle of the Soviet Army Defending Stalingrad and the Caucasus: Reflection in Indian Political Writings, Poetry and the Press. Activation of All India Movement for Immediate Opening of the Seconds Front (August 1942- February 1943) 106 Anti-Fascist Poets and Writers 114 THE YEAR 1943 129 Demands in India for Unity of Anti-Hitler Coalition 132 FSU Activities and Growth of Interest in the USSR as a Socialist Country 139 The Indian Press Against Anti-Sovietism and Anti - Communism 157 THE YEAR 1944 173 “Can we Ever Forget this Noble Deed?” 175 First All India Congress of Friends of Soviet Union 181 Order of Red Star for Indian Soldiers 213 Noor-Unnisa — A Brave Daughter of India 224 THE YEAR 1945 231 “With Berlin will Fall into Dust the Entire Edifice of Hitlerian Ambition” 233 Inscription with Blood of a Glorious Chapter in Man’s History 248 SELECT BIBLIOGRAPHY 261 4 INTRODUCTION 5 “There is a Beacon shining through the clouds of destiny. -

Ashmolean Museum from Wikipedia, the Free Encyclopedia

Ashmolean Museum From Wikipedia, the free encyclopedia The Ashmolean Museum (in full the Ashmolean Museum of Art and Archaeology) on Beaumont Street, Oxford, Ashmolean Museum England, is the world's first university museum.[1] Its first building was erected in 1678–1683 to house the cabinet of curiosities that Elias Ashmole gave to the University of Oxford in 1677. The museum reopened in 2009 after a major redevelopment. In November 2011, new galleries focusing on Egypt and Nubia were also unveiled. In May 2016, the museum opened new galleries of 19th-century art. Contents Main Museum Entrance 1 History 2 Renovation 3 Collections 4 Collections gallery 5 Broadway Museum and Art Gallery 6 Major exhibitions 7 Keepers and Directors Location in Oxford 8 In popular culture 8.1 Comics Established 1683 8.2 Literature Location Beaumont Street, Oxford, England 8.3 Stage productions Coordinates 51.7554°N 1.2600°W 8.4 Television 9 Theft Type University Museum of Art and 10 See also Archaeology 11 References 12 External links Director Dr Alexander Sturgis Website www.ashmolean.org History The collection includes that of Elias Ashmole, which he had collected himself, including objects he had acquired from the gardeners, travelers, and collectors John Tradescant the elder and his son, John Tradescant the younger. The collection included antique coins, books, engravings, geological specimens, and zoological specimens—one of which was the stuffed body of the last dodo ever seen in Europe; but by 1755 the stuffed dodo was so moth-eaten that it was destroyed, except for its head and one claw.