Indigenous Qualitative Research Report

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Junior Convenor's Report Poloc Cricket Club AGM, February 2013 I

Junior Convenor's Report Poloc Cricket Club AGM, February 2013 I'm please to bring another report on the club's juniors to the members. And in doing so I will start with the blatantly obvious: 2012 was another wet,….. very wet, season. So wet in fact that no fewer than 49 junior matches were scheduled only to be cancelled. Astonishingly, that's more than some clubs play in a full dry season! But perhaps we shouldn't have been surprised given – if I recall correctly – the last junior game of the previous season, an Under 11 home match against West of Scotland, had been abandoned with a West batter in tears in a muddy crease and unable to run on the slippery track, horizontal rain lashing across the ground! We should've seen this as an ominous sign! But of course there's more to the club's junior programme than just the summer season. Quite literally we are able to offer year-round cricket for our juniors. At present we are coaching juniors of all ages for two hours every Sunday – these sessions continue until April. We also introduced two-hour indoor Friday night sessions before Christmas for our older juniors and students, and from next week we have two-hour Monday evening sessions as well, again for our older juniors and students. I am convinced, therefore, that, as a club, we offer as comprehensive a junior coaching and practice programme as there is in the west of Scotland. The challenge is, of course, to make the quality of what we do as high as the quantity. -

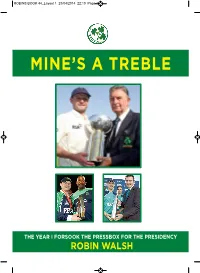

Mine's a Treble

ROBINS BOOK 44_Layout 1 23/04/2014 22:10 Page 1 MINE’S A TREBLE THE YEAR I FORSOOK THE PRESSBOX FOR THE PRESIDENCY ROBIN WALSH ROBINS BOOK 44_Layout 1 23/04/2014 22:10 Page 2 CRICKET WRITERS of IRELAND The Cricket Writers of Ireland is a small group of those who write about and photograph the game we love. Robin Walsh was President from the foundation of the organisation at Stormont in 2007 until he stepped down early in 2013 to take up the Presidency of Cricket Ireland. The CWI are immensely proud that one of our number should be recognised thus and doubly so that Robin filled the role with such dignity and commitment. It turned out to be both a tremendously successful year on the pitch and a historic one off it, and we are fortunate that a man with a trained eye and stylish pen was there to witness it all — and share it with us. Throughout his presidency Robin wrote a regular diary which appeared on the Cricket Ireland website but it clearly deserves a larger audience and a permanent place on the growing shelf of Irish cricketing literature. And that’s why you’re reading this now. ‘Mine’s a Treble’ © Robin Walsh May 2014 Published by the Cricket Writers of Ireland Designed and edited by Ger Siggins Photographs by Barry Chambers. Thanks also to Andrew Leonard 2 ROBINS BOOK 44_Layout 1 23/04/2014 22:10 Page 3 A Heartbreaking Defeat June 12th 2013 NE of the many delights of wearing since the terrorist attack on the Sri Lankan Cricket Ireland’s Presidential blazer players in Lahore in 2009. -

2015 Cricket World Cup Fantasy Cricket Competition

2015 CRICKET WORLD CUP FANTASY CRICKET COMPETITION GAME GUIDE ENTRY DETAILS Entry Costs League is FREE to enter but in order to qualify for prizes the following fees are required. One Team = £5 Two Teams = £10 Three Teams = £10 (third team is free) Entry Methods Online = E-mail team sheet to [email protected] Facebook = Message Preston Village CC page with squad Twitter = Message @PVCC_1990 with squad Paper = Return entry form to one of the following Preston Village members Craig Patterson Ian Patterson CALENDAR DEADLINES 12th February: Teams and Entry Fee Deadlines 13th February: Start of World Cup Stage 1 21st March: End of World Cup Stage 1 21st March - 24th March: Transfer Window (between quarter-final and semi-final) 24th March: Start of World Cup Stage 2 30th March: End of World Cup Stage 2 6th April - 12th April: Final Scores Calculated and Awards Presented PRIZES 1. First Prize = 50% of all entry fees + Bottle of whiskey (TBC) 2. Second Prize = Bottle of vodka or wine (TBC) 3. Third Prize = Crate (12 cans/bottles) of lager or beer (TBC) Alcoholic prizes can be exchanged for cash amount on basis of participant's age or religious beliefs. HOW TO PLAY Team Selection Select a team of 11 players from the playing squads at the World Cup, meeting the formation immediately below and the team restrictions listed below the formation 6x Batsman (minimum of one batsman/wicketkeeper who is nominated as wicketkeeper) 1x All-Rounder 4x Bowlers Team Restrictions Stage 1: Pool Stage & Quarter-Finals Maximum of 3 players per nation . -

Cricket Irelandannual Report 2015

Cricket Ireland Annual Report 2015 Chairman’s Report In my report last year I commented that, from a playing In the Inter-Continental Cup two comprehensive victories against perspective, it seemed to be a“quiet year”. The same could not Namibia and the UAE will set us up well for 2016. be said for 2015 when we saw Irish teams travel the globe. On top of that we hosted ODIs against England and Australia, a I think it would be fair to say our performance in the ICCWorld three-match series against the full AustralianWomen’s squad T20 Qualifier was possibly not what we expected and and, just for good measure, the Men’s ICCWorldT20 qualifying disappointing considering we were hosting and on our home tournament. grounds. That said, we managed to scramble through to qualify in third place. Prior to the 2015 ICC CricketWorld Cup, a number of people had been lamenting the fact that we had not beaten a full member The women’s squad again had an outstanding year with possibly in a One-Day International in four years. That all changed with a two highlights. The first being the three-matchT20I series bang in Nelson in the first game of theWorld Cup. TheWest against Australia, where they were ran very tight in at least one. Indies posted over 300 and Ireland chased it down comfortably – The biggest one, however, must be the winning of the ICCWorld RossMcCollum probably the best and most professionally comprehensive run T20 Qualifier inThailand – what an achievement that was! chase we have seen from an Irish team to date. -

Inter-Provincial Series 2018 Player Eligibility & Squad

INTER-PROVINCIAL SERIES 2018 PLAYER ELIGIBILITY & SQUAD SELECTION POLICY 1. BACKGROUND/CONTEXT 1.1 With the Inter-Provincial Series now carrying First-Class and List-A status, the need to ensure that player eligibility is both clear, and adhered to, remains important, and maintaining the integrity of the competitions is key, given that ICC retains the authority to remove First-Class/List-A status from same at any time. 1.2 The Inter-Provincial Series (First Class, One day 50 over and Twenty20) is designed to provide a bridge between club and country and to ensure players have the opportunity to compete in a ‘best v best’ environment. It is crucial to the succession planning of the Irish team. Therefore players identified by the national selectors as potential future International cricketers are given the opportunity to play in the Inter-Provincial Series. Where there is a significant strength of such players in one provincial union, we must ensure players are able to develop by playing in the IP competition perhaps for another union. 1.3 The series is also important for the individual provincial unions as a way of raising the profile of the sport, providing opportunities for their best club cricketers, helping to underpin the growth of the sport, and underpinning commercial activities of the unions. ELIGIBILITY REGULATIONS Depending on the status of the player concerned, the following eligibility criteria will apply: 2.0 NATIONALITY QUALIFICATION CRITERIA 2.1 A Player shall be qualified to participate in an Inter-Provincial Match where he satisfies at least one of the following requirements (the “Nationality Qualification Criteria”): NOTE: The relevant information and documentation required to evidence satisfaction of the Nationality Qualification Criteria must be provided to CI at least 7 days prior to the player playing in an Inter-Provincial match. -

Desert T20 Schedule Finally Released

Desert T20 schedule finally released Eight of the top Associates in Cricket collaborate to bring the inaugural Desert T20 tournament to the United Arab Emirates. To be played in the United Arab Emirates during January 2017, the 7-day tournament will commence play on Saturday January 14th at Abu Dhabi Cricket Club’s Zayed Cricket Stadium, and will continue daily through to January 17th before relocating to Dubai Sports City’s International Cricket Stadium for the final 2-days of match play, culminating in the finals on Friday January 20th. Associate countries participating include Afghanistan, Hong Kong, Ireland, Namibia, Netherlands, Oman, Scotland, and the UAE. “Emirates Cricket Board are delighted to collaborate with the participating Associates to bring this inau- gural T20 tournament to the UAE. The aim of the tournament is to provide an opportunity for our teams to play more competitive Men’s T20 cricket.” said Zayed Abbas, Emirates Cricket Board Member. “Each of the participating countries are very close in ICC T20I rankings, so we expect the quality of cricket to be very strong”. Drawn in to Pool A are Afghanistan (9), Ireland (17), Namibia (NR), and the UAE (14). While in Pool B contains The Netherlands (11), Scotland (13), Oman (16) and Hong Kong (15). “With the world class practice facilities and playing surfaces available to us in the UAE, we are confident each Associate will benefit greatly from this tournament. We extend our sincere thanks to the participat- ing Unions, the ICC and the ICC Academy for their support and commitment to this tournament.” added Abbas. -

Annual Report 2017

CRICKET IRELAND ANNUAL REPORT 2017 MAKING CRICKET MAINSTREAM Members of Cricket Ireland c/o Unit 22, Grattan Business Park Clonshaugh Dublin 17 Ireland 26 April 2018 Dear Members, We are pleased to present the Cricket Ireland Annual Report 2017 – providing an overview of the financial and operational achievements of Cricket Ireland (also known as The Irish Cricket Union Company Limited by Guarantee). Best wishes Ross McCollum Warren Deutrom Chairman Chief Executive Cricket Ireland Cricket Ireland 01 CRICKETIRELAND ANNUAL REPORT 2017 1 OVERVIEW About Cricket Ireland 4 Chairman’s Report 5 Chief Executive’s Report 6 2 PERFORMANCE REPORTS High Performance 8 International Men’s Programme 8 International Women’s Programme 8 Domestic Men’s Inter-Provincial & Women’s Super 3’s 9 Wolves, Academy and International Youth 9 Participation 10 Commercial 12 3 COMMITTEE REPORTS Cricket Committee 16 Finance Committee (including financial statements) 18 1 OVERVIEW 03 CRICKET IRELAND ANNUAL REPORT 2017 ABOUT CRICKET IRELAND Cricket Ireland is the national governing body for the sport of cricket in Ireland. It is responsible for setting the strategic direction and the national administration of cricket on the island of Ireland. Cricket Ireland (also known as “The Irish NATIONAL RE-EMERGENCE GOVERNANCE STRUCTURE Cricket Union Company Limited by Guarantee”) was established in 1923, Proper competitive national fixtures There are 12 Directors on the Board of originally with a brief to organise the began for Ireland in 1980 with entry to Cricket Ireland, five of which are national squad, primarily arranging the English Gillette Cup, and while it independent. Five provincial bodies fixtures against the Scotland and the was a long road to becoming a have responsibility for the game in their English MCC, as well as occasional visits competitive side, a turning point respective regions, while key standing by English Counties and Test teams. -

To View November 2020 Newsletter

NOVEMBER 2020 EDITION PRESIDENT EMERITUS: Arthur Vincent www.lordstavernersireland.ie PRESIDENT: Michael Moriarty HAIRMAN www.facebook.com/lordstavernersireland C : Paul Farrell CHY 18470 Ambassador: Ed Joyce LORD’S TAVERNERS IRELAND Taverners’“Giving young people, particularly those with special taleS needs, a sporting chance” YOUR CONTRIBUTIONS CONTINUE TO HELP CHANGE LIVES AND MAKE A DIFFERENCE! The Coronavirus pandemic is, of course, dominating all our thoughts and has resulted in a shocking loss of life and huge disruption to all aspects of our lives. The Charity Sector has also been exceptionally badly hit but with your help, Lord’s Taverners Ireland will continue our good work and “give young people, particularly those with special needs, a sporting chance”. Just two short weeks ago, we were thrilled to deliver two vans to the Irish Wheelchair Association (IWA), and they are already whizzing around the country! These sport vehicles will support a range of sports including all IWA governing sports such as Wheelchair Basketball, Wheelchair Rugby, Para powerlifting and Para Athletics. The IWA transport as many sport wheelchairs as possible to all their sports events as sports wheelchairs are an expensive purchase for families and athletes and many individuals and newcomers to the sports don’t have their own. These vans will ensure the IWA team can provide wheelchairs at all games which will ensure inclusion for those who want to join, bringing a relief to families all across Ireland. Lord’s Taverners Ireland have proudly worked alongside the IWA for some time and are thrilled to have worked with them on this project. -

Randwick Petersham V Cricket Ireland the New Balance Community Cricket Week International Cup

Randwick Petersham v Cricket Ireland The New Balance Community Cricket Week International Cup There had been quite a buzz around Randwick Petersham Cricket Club for many months at the prospect of hosting a match against the ICC 2015 Cricket World Cup contender Ireland. The game had been set down for Friday 6 February at the “Randy Petes’” home ground, the picturesque sea-side Coogee Oval and was to be the culmination of a week of practice and preparatory work for the Ireland squad. And to add to the excitement, just prior to their arrival, Ireland was granted full One Day International (ODI) status. This was the first opportunity for Randwick Petersham to have a taste of international competition with the result every member of the current 1st Grade team made themselves available for the clash despite it being played on a work day. Initial discussions for the composition of the team surrounded it being a Randwick Petersham Invitational XI. It was also a big occasion for the local community as they had not been treated to a sporting match of such stature since the All Blacks played Randwick Rugby Club at Coogee in 1988 before a crowd of over 9,000. The match was the outcome of a discussion some 18 months earlier between two of the cricket club’s promising young administrators, John Stewart and John McLoughlin. Stewart (29) is the enthusiastic curator of the club’s museum located in the Coogee Oval pavilion while McLoughlin (34) is the developer and manager of the club’s website. Both captain club teams and also sit on the sponsorship committee. -

Match Report

Match Report Zimbabwe, ZIM vs Ireland, IRE Ireland, IRE - Won (D/L method) Date: Fri 12 Jul 2019 Location: Ireland - Northern Match Type: Twenty20 Scorer: Akhilesh Babu Toss: Ireland, IRE won the toss and elected to Bowl URL: https://www.crichq.com/matches/931724 Zimbabwe, ZIM Ireland, IRE Score 132-8 Score 134-1 Overs 13.0 Overs 10.5 BRM Taylor † PR Stirling Hamilton Masakadza * KJ O'Brien Craig R Ervine A Balbirnie SC Williams GC Wilson *† Sikandar Raza MR Adair Ryan P Burl G Delany Peter J Moor SC Getkate Richmond Mutumbami TE Kane KM Jarvis GJ Thompson Chris Mpofu L Tucker Tendai L Chatara CA Young page 1 of 33 Scorecards 1st Innings | Batting: Zimbabwe, ZIM R B 4's 6's SR BRM Taylor † . 4 . 1 . 1 4 . 4 . // c L Tucker b MR Adair 14 11 3 0 127.27 Hamilton . 1 . // c KJ O'Brien b CA Young 1 4 0 0 25.0 Masakadza * Craig R Ervine . 4 . 4 . 1 4 . 1 1 . 2 6 1 1 6 1 4 1 1 6 . 1 4 . 1 4 1 . // c TE Kane b MR Adair 55 32 6 3 171.88 SC Williams 4 4 1 . 4 1 6 1 6 6 1 . // c PR Stirling b MR Adair 34 12 3 3 283.33 Sikandar Raza . 1 . 2 . // c MR Adair b SC Getkate 3 6 0 0 50.0 Ryan P Burl . 2 . 1 4 1 4 1 // run out (SC Getkate/GC Wilson *†) 13 8 2 0 162.5 Peter J Moor 4 . -

Cricket Prog 1

14th – 20th July 2009 JERSEY PEPSI ICC Development Programme – Europe The PEPSI ICC European Development Program started in 1997 and in Europe now involves 12 Associate and 18 Affiliate member countries as well as 12 Prospective member countries. The program is run by seven staff at the ICC Europe headquarters at Lord’s Cricket Ground in London and has four strategic goals. ICC’s mission statement is complemented by a Vision of Success and values for the sport. As the international governing body of cricket, the International Cricket Council will lead by: • Promoting and protecting the game and its unique spirit • Delivering outstanding, memorable events • Providing excellent service to Members and stakeholders • Optimising its commercial rights and properties for the benefits of its members. “As a leading global sport, cricket will captivate and inspire people of every age, gender, background and ability while building bridges between continents, countries and communities. Our values: • Cricket: a strong sport getting stronger • Performance with integrity • Elite performances in an elite environment • Ethical behaviour • Prestigious events • Unity and shared purpose • A traditional game which adapts • No corruption • Integration of women’s cricket • Operational Excellence • Increased competitiveness • The unique Spirit of Cricket • Heroes and role models • Quality member and stakeholder services • Sustainable growth • Meeting and responding to Members needs • Financial strength and security • Helping members to help themselves • Strengthening of ICC’s regional operations • Member’s charter • Quantity and quality of participation • Membership structures • Meaningful competition • Effective stakeholder relations • Cricket in commercial demand 2 ICC Europe Office The Clock Tower Lord’s Cricket Ground London NW8 8QN T +44 (0) 20 7616 8635 F +44 (0) 20 7616 8634 E [email protected] www.icc-europe.org It gives me great pleasure to welcome all teams, players and officials to Jersey for the ICC European Division 1 U/19 Cricket World Cup (CWC) Regional Qualifier. -

ICC Annual Report 2015-16

ANNUAL REPORT 2015-2016 Including Summarised Financial Statements BELOW: Australia team celebrates with the Trans-Tasman Trophy after winning the second Test against New Zealand in Christchurch on 24 February 2016. Australia finished as the number-one ranked Test side at the 1 April cut-off date and also retained the top position after the 1 May annual update. 01 CONTENTS FOREWORD Chairman’s Report ...................................................................... 02 Chief Executive’s Report.............................................................04 ICC Strategy 2016-2019 ............................................................. 06 Highlights of the Year ................................................................. 08 Obituaries ..................................................................................... 12 Retirements .................................................................................. 15 THE WORLD’S FAVOURITE SPORT Governance of the Global Game ................................................ 18 ICC Members ................................................................................ 21 Cricket ...........................................................................................22 Development .............................................................................. 24 Commercial ..................................................................................26 Anti-Corruption ...........................................................................28 Anti-Doping..................................................................................29