Whacking Bush Final

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

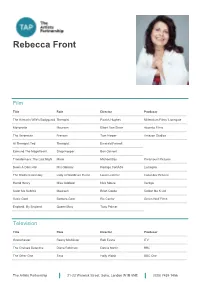

Rebecca Front

Rebecca Front Film Title Role Director Producer The Hitman's Wife's Bodyguard Therapist Patrick Hughes Millennium Films/ Lionsgate Marionette Maureen Elbert Van Strain Accento Films The Aeronauts Frances Tom Harper Amazon Studios AI Therapist Ted Therapist Emerald Fennell Edmund The Magnificent Shop Keeper Ben Ockrent Transformers: The Last Night Marie Michael Bay Paramount Pictures Down A Dark Hall Mrs Olonsky Rodrigo Cortés Lionsgate The Brothers Grimsby Lady at Worldcure Event Louis Leterrier Columbia Pictures Horrid Henry Miss Oddbod Nick Moore Vertigo Color Me Kubrick Maureen Brian Cooke Colour Me K Ltd Suzie Gold Barbara Gold Ric Cantor Green Wolf Films England, My England Queen Mary Tony Palmer Television Title Role Director Producer Grantchester Reeny McAllister Rob Evans ITV The Chelsea Detective Diana Robinson Darcia Martin BBC The Other One Tess Holly Walsh BBC One The Artists Partnership 21-22 Warwick Street, Soho, London W1B 5NE (020) 7439 1456 Avenue 5 (Series 1 and 2) Karen Kelly Armando Iannucci and Various HBO Dark Money (US Title Shattered Dreams)Cherly Denon Lewis Arnold The Forge Entertainment/ BBC One Death In Paradise Fiona Tait Stewart Svaasand ITV Poldark Lady Whitworth Various BBC One The Other One (Pilot) Tess Dan Zeff BBC Queers Monologue Alice Mark Gatiss BBC Love, Lies & Records Judy Dominic LeClerc & Cilla Ware ITV War And Peace Anna Mikhailovna Dubetskaya Tom Harper Weinstein Co Doctor Thorne Lady Arabella Gresham Matt Lipsey Weinstein Co Billionaire Boy Miss Sharp Matt Lipsey King Bert Up The Woman Helen Christine Gernon Baby Cow Productions The Eichmann Show Mrs. Landau Paul Andrew Williams Feelgood Fiction Humans Vera Sam Donovan Kudos Doctor Who Walsh Daniel Nettheim BBC Psychobitches The Therapist Various Tiger Aspect Outnumbered Mrs. -

Arthur Mathews

Arthur Mathews Agent Katie Haines ([email protected]) In Development: PREPPERS (BBC Comedy) FLEMP (Roughcut Television) TOOTHTOWN with Simon Godley (Yellow Door Productions) Television: ROAD TO BREXIT (Objective/BBC Two) Starring Matt Berry TOAST OF LONDON (Objective/C4) Series 1, 2 & 3 Co-written with Matt Berry Nominated for BAFTA Best Situation Comedy 2014 Winner of the Rose d'Or for Best Sitcom at the 53rd Rose d'Or Festival 2014 Nominated for an RTS Programme Award 2013 TRACEY ULLMAN SHOW (BBC) 2015/16 Sketches FORKLIFTERS (Channel 4) VAL FALVEY (Grand Pictures / RTE1) Series 2 2010; Series 1 2008-9 6 x 30’ - co-written with Paul Woodfull Co-Director (Series 1) THIS IS IRELAND (CHX / BBC2) 2004 Writer and Script Editor BIG TRAIN (Talkback Productions / BBC2) Series 1 & 2 1998-2001 Co-Creator and Writer HIPPIES (Talkback Productions / BBC) 1999 Co-created and co-written with Graham Linehan FATHER TED (Hat Trick Productions / Channel 4) 3 Series 1995-1998 Co-created & Co-written with Graham Linehan HARRY & PAUL (Tiger Aspect Productions / BBC) SERIES C 2010 Various sketches THE EEJITS (Objective / Channel 4) 2007 Comedy Showcase Pilot MODERN MEN (TalkbackThames/Channel 4) 2007 Guest Writer / Script Editor for Armstrong & Bain IT CROWD (TalkbackThames/Channel 4) Series 2 2006 Writing Consultant STEW (Script Editor and Writer) 2003 -2006 Grand Pictures for RTE THE CATHERINE TATE SHOW (Tiger Aspect/BBC2) Series 1 & 2 2004/2005 Sketch Material BRASS EYE (TalkBack /Channel 4) 1997 Various Sketches THE FAST SHOW (BBC2) 1994-1997 -

P&C Music Rsd 2016

P&C MUSIC RSD 2016 - 20% DISCOUNT OFF ALL PRICES BELOW! ARTIST / TITLE PRODUCT INFO £ 1. ALAN PARTRIDGE: Knowing me, knowing you Picture disc of 2x30 minute BBC4 radio shows. Features the comic talents of Armando Iannucci 26.99 (The Thick of it), Doon MacKichan (Toast Of London, The Day Today), Rebecca Front (The Thick of it, The Day Today, Dr. Thorne) and David Schneider (The Day Today, I'm Alan Partridge). 1000 hilarious copies. 2. ANCHORESS, The: Popular / What goes around (string Following the critically-acclaimed release of her debut album, Confessions of a Romance 7.99 version) Novelist, The Anchoress (aka Catherine AD) has released a special limited 7” single for RSD16. 3. ANIMAL NOISE: Sink or swim 7” EP, 500 copies. 7.99 4. AANIMALS, The: Animal tracks 10”, four-track EP, 45rpm. Their fourth EP reissued in this new size format. We were unable to 19.99 US RSD RELEASE obtain this US RSD title until after Record Store Day. 5. ANTI-FLAG: Live Acoustic at 11th Street Records, Las Clear vinyl LP + download card, previously only available digitally. This American punk band 20.99 Vegas recorded this 9-track set in Spring 2015. 6. ARTHUR BEATRICE: Every cell 12” single, blue vinyl. 500 copies. 9.99 7. ASHFORD AND SIMPSON: Love will fix it – the best of 2LP, 1000 copies. This newly re-mastered comprehensive release features 19 of the duo’s 31.99 Ashford and Simpson classic progressive 70s R&B duets. It didn’t arrive in time for RSD, but here it is now. -

12Th & Delaware

12th & Delaware DIRECTORS: Rachel Grady, Heidi Ewing U.S.A., 2009, 90 min., color On an unassuming corner in Fort Pierce, Florida, it’s easy to miss the insidious war that’s raging. But on each side of 12th and Delaware, soldiers stand locked in a passionate battle. On one side of the street sits an abortion clinic. On the other, a pro-life outfit often mistaken for the clinic it seeks to shut down. Using skillful cinema-vérité observation that allows us to draw our own conclusions, Rachel Grady and Heidi Ewing, the directors of Jesus Camp, expose the molten core of America’s most intractable conflict. As the pro-life volunteers paint a terrifying portrait of abortion to their clients, across the street, the staff members at the clinic fear for their doctors’ lives and fiercely protect the right of their clients to choose. Shot in the year when abortion provider Dr. George Tiller was murdered in his church, the film makes these FromFrom human rights to popular fears palpable. Meanwhile, women in need cuculture,lt these 16 films become pawns in a vicious ideological war coconfrontnf the subjects that with no end in sight.—CAROLINE LIBRESCO fi dedefine our time. Stylistic ExP: Sheila Nevins AsP: Christina Gonzalez, didiversityv and rigorous Craig Atkinson Ci: Katherine Patterson fifilmmakingl distinguish these Ed: Enat Sidi Mu: David Darling SuP: Sara Bernstein newnew American documentaries. Sunday, January 24, noon - 12DEL24TD Temple Theatre, Park City Wednesday, January 27, noon - 12DEL27YD Yarrow Hotel Theatre, Park City Wednesday, January 27, 9:00 p.m. - 12DEL27BN Broadway Centre Cinemas VI, SLC Thursday, January 28, 9:00 p.m. -

Alpha Papa Alan Partridge Stream

Alpha papa alan partridge stream Watch Alan Partridge: Alpha Papa Online | alan partridge: alpha papa | Alan Partridge: Alpha Papa. Watch Alan Partridge Alpha Papa Online - Free Streaming Full Movie on Putlocker. The primary series of I am Alan Partridge was IMO the best comedy. Alan Partridge: Alpha Papa Radio DJ Alan Partridge experiences a difficult time when his radio station seems to be forced by a new media group. He puts. Watch Alan Partridge: Alpha Papa with Subtitles Online For Free in HD. Free Download Alan Partridge: Alpha Papa. Watch free movie Streaming now. Alan Partridge: Alpha Papa () - Alan Partridge has had many high points and low points in life. National TV supporter. In charge of executing a visitor on live. Alan Partridge: Alpha Papa: Watch online now with Amazon Instant Video: Steve Coogan, Colm Meaney, Format, Amazon Video (streaming online video). Watch alan partridge: alpha papa movies Online. Watch alan partridge: alpha papa movies online for free on Alan Partridge: Alpha Papa Alan Partridge has had many ups and downs in life. Please create an account to access unlimited downloads and streaming. Watch Alan Partridge: Alpha Papa starring Steve Coogan in this Comedy on DIRECTV. It's available to watch. Buy Alan Partridge: Read 88 Movies & TV Reviews - Purchase rights, Stream instantly Details. Format, Amazon Video (streaming online video). Is Netflix, Amazon, Hulu, Crackle, iTunes, etc. streaming Alan Partridge: Alpha Papa? Find where to watch online! Does Netflix, Quickflix, Stan, iTunes, etc. stream Alan Partridge: Alpha Papa? Find where to watch online! Click Here: ® ® Alan Partridge: Alpha Papa Full Movie Online HD ® ® | Watch Alan Partridge: Alpha. -

Aafjufj Fpjpw^-Itkalfcic BILLY Rtiabrir/ HIATUS ^ ^Mrc ^ ^International

THAT MSAZlNf FKOm CUR UM.* ftR AAfJUfJ fPJpw^-iTKAlfCIC BILLY rtiABrir/ HIATUS ^ ^mrc ^ ^international 06 I 22 Ex-Centric Sound System / Velvet 06 I 23 Cinematic Orchestra DJ Serious 06 I 24 The New Deal / Q DJ Ramasutra 06 I 26 Bullfrog featuring Kid Koala Soulive 06 I 30 Trilok Gurtu / Zony Mash / Sex Mob PERFORMANCE WORKS SRflNUILLE ISLRND 06 ! 24 Cinematic Orchestra BULLFROG 06 1 25 Soulive 06 127 Metalwood ^ L'" x**' ''- ^H 06 1 28 Q 06 1 29 Broken Sound Barrier featuring TRILOK GURTU Graham Haynes + Eyvind Kang 06 130 Kevin Breit "Sisters Euclid" Heinekeri M9NTEYINA ABSOLUT ^TELUS- JAZZ HOTLINE 872-5200 TICKETMASTER 280-4444 WWW.JAZZVANCOUVER.COM PROGRAM GUIDES AT ALL LOWER MAINLAND STARBUCKS, TELUS STORES, HMV STORES THE VANCOUVER SUN tBC$.radiQ)W£ CKET OUTLETS BCTV Music TO THE BEAT OF ^ du Maurier JAZZ 66 WATER STREET VANCOUVER CANADA Events at a glance: \YJUNE4- ^guerilla pres ERIK TRUFFAZ (Blue Note) s Blue Note signed, Parisian-based trumpe t player Doors 9PM/$15/$12 ir —, Sophia Books, Black S — Boomtown, Bassix and Highlife guerilla & SOPHIA Bk,w-> FANTASTIC PLASTIC MACHINE plus TIM 'LOVE' LEE fMfrTrW) editrrrrrrp: Lyndsay Sung gay girls rock the party by elvira b p. 10 "what the hell did i get myself DERRICK CARTER© inSOe drums are an instrument, billy martin by sarka k p. 11 into!!! je-sus chrisssttf!" mirah sings songs, by adam handz p. 12 ad rep/acid kidd: atlas strategic: wieners or wankers? by lyndsay s. p. 13 Maren Hancock Y JUNE 10 - SPECTRUM ENT pres bleepin' nerds! autechre by robert robot p. -

Easter 2013 CUS Standing Committee Easter 2013 President’S

Easter 2013 CUS Standing Committee Easter 2013 President’s President Speakers’ Officer Executive Officer Treasurer Social Events Officer Joel Fenster Imogen Schön Emily Gittins Daniel Hyman Lucy Lassman Welcome Welcome back to Vice President President Elect Vice President Debating Officer Debating Officer Easter Term at the Designate Cambridge Union. Alex Forzani Joanna Mobed Will Thong Ali Roweth Alex Porter The next few weeks are packed with Speakers Officer Elect: Oliver Jackson Treasurer Elect: Michael Dunn Goekjian events, so be sure to take a moment to plan your revision breaks. With speak- Head of Press Joanne Stewart Supplementary Committee ers ranging from Tim Deputy Head of Press Valdemar Alsop Ted Loveday Zuzanna Grześkiewicz Rachel Tookey Minchin to Michael Head of Campus Publicity Leo Kirby Krista Länkelä Sandel, we have Head of Online Publicity Ian Cooper Nick Wright tried to deliver Deputy Heads of Publicty Will Taylor, Katharine Biddle Rupert Campbell-Manners something for all tastes. With Lisa Kudrow, Bradley Whitford, Armando Iannucci, SGL for Debates Tom Earl Coordination Committee the Palestinian Ambassador, and so many more, I know that there is someone here SGL for Speakers James Hutt Leo Kirby Deputy SGLA Zahra Sachedina for you. Will Taylor HOEM Clara Spera James Hutt Deputy HOEM Matt Townsend Zuzannna Grześkiewicz Moving on to debates, speakers include Mike Newell, Jimmy Wales, Lily Cole, Secretary Ellen Powell Amy Gregg Natalie Bennett, Francis Boulle, Kate Pickett, and many other leading figures. Our Women’s Officer Christina Sweeney-Baird Nick Wright debates this term address pressing matters of our time, including Iran’s nuclear Diversity Officers Will Prasifka, Amy Gregg Jiameng Gao Recruitment Officers Stephanie Tan, Tim Squirrell ambitions and the Israeli-Palestinian conflict. -

Masaryk University Brno

Masaryk University Brno FacultyofEducation Department of English Language and Literature Contemporary British Humour Bachelor thesis Brno 2007 Supervisor: Written by: Mgr. Lucie Podroužková, PhD. Kateřina Matrasová Declaration: I declare that I have written this bachelor thesis myself and used only the sources listed in the enclosed bibliography. I agree with this bachelor thesis being deposited in the Library of the Faculty of Education at the Masaryk University and with its being made available for academic purposes. ................................................ Kateřina Matrasová 2 Acknowledgements I would like to thank to Mgr. Lucie Podroužková, PhD. I am grateful for her guidance and professional advice on writing the thesis. 3 Contensts Introduction…………………………………………………………………………………...5 PartOne……………………………………………………………………………………….7 1.Humour …………………………………………………………………………………….7 2.Laughter …………………………………………………………………………………..11 3.Comedy,VerbalHumourandGenres…………………………………………………….14 4.VerbalHumouronTelevisionandRadio……………………...........................................15 5.Britishness……………………………………………………...........................................17 PartTwo……………………………………………………………………………………..22 6.ContemporaryBritishComedians……………………………...........................................22 7.1.SachaCohenandhisalteregos …………………………………………………………22 7.2.AliG…………………………………………………………………………………….23 7.3.Bruno……………………………………………………………………………………25 7.4.Borat …………………………………………………………………………………….27 8.ChristopherMorrisandhiscomedyworks……………………………………………….30 8.1.BrassEye………………………………………………………………………………..31 -

Last Christmas

NEW EXHIBITION YOUR LOCAL CINEMA NOVEMBER & DECEMBER 2019 EMPOWERING PEOPLE GENETIC COUNSELLING IN FOCUS What is a genetic counsellor, and who gets to see one? Discover more in a new exhibition at the Wellcome Genome Campus Visit the exhibition and more during one of our upcoming Open Saturdays 1 - 4pm on 16th Nov, 21st Dec, 18th Jan, 15th Feb Wellcome Genome Campus | Hinxton | CB10 1SA BOOK YOUR FREE TICKETS: LAST CHRISTMAS wgc.org.uk/engage/events BOOK NOW AT THE CINEMA BOX OFFICE, TIC OR ONLINE www.saffronscreen.com CINEMA INFORMATION VISITS FROM TICKETS FOR ALL FILMS ARE NOW ON SALE SANTA! DAYTIME Full £7.30; 65 & over £6.50; other adult concessions £5.40; 16-30 £5.00; under 16s £4.60; family tickets (2 adults + 2 children or 1 adult + 3 children) £20.50 EVENINGS (films at or after 5pm) Full £8.40; 65 & over £7.80; other adult concessions £6.30; 16-30 £5.50; under 16s £5.20 (30 & under £4.50 Monday nights) A SHAUN THE THE MUPPET CINEMA FOR TINIES Adults £4.00; children £3.00; under 2s free JUDY SHEEP MOVIE CHRISTMAS CAROL ARTS ON SCREEN Please see ticket price information for each event. See our website for information about eligibility for concession price tickets Tickets are available: WELCOME ● online at www.saffronscreen.com (booking fee applies) ● in person from the Box Office (opens 30 mins before each screening) ● in person from the Tourist Information Centre, Saffron Walden As we round off the year with an exciting slate of films and live (booking fee applies) (telephone: 01799 524002, enquiries only). -

The Stone Roses Music Current Affairs Culture 1980

Chronology: Pre-Stone Roses THE STONE ROSES MUSIC CURRENT AFFAIRS CULTURE 1980 Art created by John 45s: David Bowie, Ashes Cinema: Squire in this year: to Ashes; Joy Division, The Empire Strikes Back; N/K Love Will Tear Us Apart; Raging Bull; Superman II; Michael Jackson, She's Fame; Airplane!; The Out of My Life; Visage, Elephant Man; The Fade to Grey; Bruce Shining; The Blues Springsteen, Hungry Brothers; Dressed to Kill; Heart; AC/DC, You Shook Nine to Five; Flash Me All Night Long; The Gordon; Heaven's Gate; Clash, Bankrobber; The Caddyshack; Friday the Jam, Going Underground; 13th; The Long Good Pink Floyd, Another Brick Friday; Ordinary People. in the Wall (Part II); The d. Alfred Hitchcock (Apr Police, Don't Stand So 29), Peter Sellers (Jul 24), Close To Me; Blondie, Steve McQueen (Nov 7), Atomic & The Tide Is High; Mae West (Nov 22), Madness, Baggy Trousers; George Raft (Nov 24), Kelly Marie, Feels Like I'm Raoul Walsh (Dec 31). In Love; The Specials, Too Much Too Young; Dexy's Fiction: Midnight Runners, Geno; Frederick Forsyth, The The Pretenders, Talk of Devil's Alternative; L. Ron the Town; Bob Marley and Hubbard, Battlefield Earth; the Wailers, Could You Be Umberto Eco, The Name Loved; Tom Petty and the of the Rose; Robert Heartbreakers, Here Ludlum, The Bourne Comes My Girl; Diana Identity. Ross, Upside Down; Pop Musik, M; Roxy Music, Non-fiction: Over You; Paul Carl Sagan, Cosmos. McCartney, Coming Up. d. Jean-Paul Sartre (Apr LPs: Adam and the Ants, 15). Kings of the Wild Frontier; Talking Heads, Remain in TV / Media: Light; Queen, The Game; Millions of viewers tune Genesis, Duke; The into the U.S. -

Claiming Chris Cunningham for British Art Cinema James Leggott Journal of British Cinema and Television 13.2

View metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk brought to you by CORE provided by Northumbria Research Link Come to Daddy? Claiming Chris Cunningham for British Art Cinema James Leggott Journal of British Cinema and Television 13.2 (2016): 243–261 Abstract: Twenty years after he came to prominence via a series of provocative, ground-breaking music videos, Chris Cunningham remains a troubling, elusive figure within British visual culture. His output – which includes short films, advertisements, art gallery commissions, installations, music production and a touring multi-screen live performance – is relatively slim, and his seemingly slow work rate (and tendency to leave projects uncompleted or unreleased) has been a frustration for fans and commentators, particularly those who hoped he would channel his interests and talents into a full-length ‘feature’ film project. There has been a diverse critical response to his musical sensitivity, his associations with UK electronica culture – and the Warp label in particular – his working relationship with Aphex Twin, his importance within the history of the pop video and his deployment of transgressive, suggestive imagery involving mutated, traumatised or robotic bodies. However, this article makes a claim for placing Cunningham within discourses of British art cinema. It proposes that the many contradictions that define and animate Cunningham’s work – narrative versus abstraction, political engagement versus surrealism, sincerity versus provocation, commerce versus experimentation, art versus craft, a ‘British’ sensibility versus a transnational one – are also those that typify a particular terrain of British film culture that falls awkwardly between populism and experimentalism. Keywords: British art cinema; Chris Cunningham; cinematic bodies; film and music; music video. -

'The Sickest Television Show Ever'

“The Sickest Television Show Ever” “The Sickest Television Show Ever”: Paedogeddon and the British Press Sharon Lockyer and Feona Attwood Sharon Lockyer School of Social Sciences Brunel University Uxbridge Middlesex, UB8 3PH Tel: +44 (0)1895 267373 Email: [email protected] Feona Attwood Sheffield Hallam University Furnival Building Arundel Street Sheffield, S1 1WB Tel: +44(0)114 2256815 Email: [email protected] 1 “The Sickest Television Show Ever” “The Sickest Television Show Ever”: Paedogeddon and the British Press Abstract This paper explores the controversy caused by Paedogeddon, a one-off special of the Channel 4 series Brass Eye, broadcast on 26 July 2001. Although the program sought to satirize inconsistencies in the way the British media treats and sensationalizes child sex offenders and their crimes (Clark, 2001), it offended many viewers and caused considerable controversy. Over 900 complaints were made to the Independent Television Commission, almost 250 complaints to the Broadcasting Standards Commission, and 2,000 complaints to Channel 4, “officially” making Paedogeddon the most complained-about television program in British television history at that time. This paper examines the nature of the objections to Paedogeddon as played out on the pages of the British national press and contributes to debates about morally acceptable television. Three themes are identified in the press objections to the mock-documentary: aesthetic arguments; moral and ethical implications; and consequences of ministerial intervention. The nature of these press objections served to prevent an engagement with Paedogeddon’s critique of the media. Further, the analysis illustrates how media discourses and scripts can fix and limit debates surrounding controversial television programming.