The Common Agricultural Policy and the Next EU Budget

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

London Book Fair 2019

London Book Fair 2019 Rights Catalogue: Frontlist Fiction FOR RIGHTS QUERIES CONTACT Nerrilee Weir, Senior Rights Manager TEL +61 2 8923 9892 FAX +61 2 9956 6487 EMAIL [email protected] penguin.com.au/rights Awards and Nominations 2019 & 2018 The Second Cure by Margaret Morgan Finalist: Aurealis Awards 2018 The Cage by Lloyd Jones Longlisted: Ockham New Zealand Book Awards 2019 The Man Who Would Not See by Rajorshi Chakraborti Longlisted: Ockham New Zealand Book Awards 2019 This Mortal Boy by FIona Kidman Longlisted: Ockham New Zealand Book Awards 2019 The Tea Gardens by Fiona McIntosh Longlisted: Australian Book Industry Awards 2018 The Girl in Kellers Way by Megan Goldin Shortlisted: Ned Kelly Awards 2018 Shortlisted: Davitt Awards 2018 Shortlisted: Australian Book Designers Awards 2018 All Day at the Movies by Fiona Kidman Longlisted: IMPAC International Dublin Literary Award 2018 Billy Bird by Emma Neale Longlisted: IMPAC International Dublin Literary Award 2018 2 LONDON 2019 FRONTLIST RIGHTS CATALOGUE RIGHTS SOLD 2018 & 2019 The Pearl Thief The Escape Room Fiona McIntosh Megan Goldin United Kingdom (Penguin North America (St Martin’s) Random House – Ebury) United Kingdom (Hachette) Italy (DeA Planeta) The Netherlands (Ambo Anthos) Audio (Penguin Random Germany (Piper Verlag) House Australia) Spain (Penguin Random House Groupo Editorial) Poland (Wydawnictwo Bukowy Las) Greenlight Benjamin Stevenson North America (Sourcebooks) This Mortal Boy United Kingdom (Hachette) Fiona Kidman United Kingdom (Gallic Books) Audio (Audible) Film Option (South Pacific Pictures) Audio (Bolinda) Potiki The Mannequin Makers Patrica Grace Craig Cliff United Kingdom (Penguin United Kingdom (Melville Random House – Penguin House) Press) Also licenced to: North America (Milkweed Editions) Romania (Editura Univers) The Yellow Villa Sixty Summers Amanda Hampson Amanda Hampson Italy (Newton Compton Editori) Audio (W. -

BIBLIOGRAPHY Story of Dr

➨ Amery, H. (2002). Usborne internet-linked first thousand ➨ Tran, R. (2003). Going home, coming home/về nhà, thǎm quẻ words in German. London: Usborne. hủỏng. (Vietnam). San Francisco: Children’s Book Press. ➨ Araujo, F.P. & Xiao-Jun Li. (1994). The perfect orange: A tale ➨ Unger de Peters, S. (1996). Mennoniten in Mexiko. (German). from Ethiopia. Windsor, CA: Rayve Productions. Steinbach, Canada: Die Mennonitische Post. ➨ Bateson-Hill, M. (1996). Lao Lao of dragon mountain. ➨ Wells, R. (1992). A to Zen. (Japan). Saxonville, MA: Picture (Chinese). New York: Stewart, Tabori & Chang. Book Studio. ➨ Bridges, S.Y. (2002). Ruby’s wish. (Chinese). San Francisco: ➨ Young, E. (2005). Beyond the great mountains: A visual poem Chronicle Books. about China. (China). San Francisco: Chronicle Books. ➨ Brooks, F. & Backinnon, M. (2006). First picture French. ➨ Zhang, S.N. (1998). The ballad of Mulan. (China). Union City, London: Usborne Publishing. CA: Pan Asian Publications. ➨ Brown, M. (2009). Pelé: King of Soccer/El rey del fútbol. Seeing (Brazil). New York: HarperCollins Publishers. ➨ Cunnane, K. (2006). For you are a Kenyan child. (Kenya). New York: Atheneum Books for Young Readers. Nonfiction Resources for Teachers ➨ ➨ DuPre, K. (2008). The travels of Igal Shīdad/Safarada Cīgaal : A Somali folktale. Illus. by A. Amir. Saint Paul, MN: ➨ Bretón, M. (2003). Home is everything: The Latino baseball : Shīdaad ME Minnesota Humanities Center. story. El Paso, TX: Cinco Puntos Press. ➨ Edwards, R. (2005). Bezpieczne miejsce matej matpki/Little ➨ Crunxin, L. (2007). Dancing to freedom: The true story of monkey’s one safe place. (Polish). Illus. by S. Winter. London: Mao’s last dancer. New York: Walker & Co. -

Heinemann Education Books HEB Introduction

Heinemann Education Books HEB The University of Reading holds the Heinemann Education Books archive which was transferred in 1987 and then subsequent deposits were accepted. The William Heinemann archive is held by Random House. There are two series of catalogued Heinemann archives at the University of Reading, Special Collections: The African Writers Series and New Windmill. The Collection covers the years 1949-1999. The physical extent of the collection is 859 files. Introduction Heinemann was founded in 1890 as William Heinemann Ltd. On Heinemann's death in 1920, one half of the company was purchased by the U.S. publisher, Heinemann during the Wall Street crash in 1929. Windmill Press, Kingswood, Surrey was the headquarters of distribution, accounting and promotion activities of the Heinemann Group of Companies. Heinemann was purchased by the Octopus Publishing Group in 1985. Octopus was purchased by Reed International (now Reed Elsevier) in 1987. Random House bought Heinemann's trade publishing (now named William Heinemann) in 1997. Heinemann's educational unit grew into an independent company in 1961. It became part of Harcourt Education when Reed Elsevier purchased the company in 2001. Pearson purchased the UK, South African, Australian and New Zealand arms of Harcourt Education in May 2007. The American operations were purchased by Houghton Mifflin. HEB NW New Windmill Series 1949-1981 Educational book series aimed at Secondary School age children. Anne and Ian Serraillier were general editors in the travel and a range of current fiction. 242 files HEB NW Correspondence relating to the publication of One day in the life 01/01 of Ivan Denisovich by Alexander Solzhenitsyn 1973-1974. -

Media Arts Centers As Alternative Archival Spaces: Investigating the Development of Archival Practices in Non-Profit Media Organizations

MEDIA ARTS CENTERS AS ALTERNATIVE ARCHIVAL SPACES: INVESTIGATING THE DEVELOPMENT OF ARCHIVAL PRACTICES IN NON-PROFIT MEDIA ORGANIZATIONS by Lindsay Kistler Mattock BA Film Studies, University of Pittsburgh, 2004 MLIS, University of Pittsburgh, 2009 Submitted to the Graduate Faculty of the School of Information Sciences in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy University of Pittsburgh 2014 UNIVERSITY OF PITTSBURGH SCHOOL OF INFORMATION SCIENCES This dissertation was presented by Lindsay Kistler Mattock It was defended on June 10, 2014 and approved by Dr. Brian Beaton, Assistant Professor, Library and Information Science Dr. Sheila Corrall, Professor, Library and Information Science Dr. Annette Vee, Assistant Professor, Department of English Dissertation Advisor: Dr. Richard J. Cox, Professor, Library and Information Science ii Copyright © by Lindsay Kistler Mattock 2014 iii MEDIA ARTS CENTERS AS ALTERNATIVE ARCHIVAL SPACES: INVESTIGATING THE DEVELOPMENT OF ARCHIVAL PRACTICES IN NON- PROFIT MEDIA ORGANIZATIONS Lindsay Kistler Mattock, MLIS, PhD University of Pittsburgh, 2014 In the United States, archival institutions have prioritized the preservation of commercial and Hollywood cinema overlooking small-scale media production by non-professionals and independent media artists. Media arts centers, however, have played a pivotal role in the continued access, use, and preservation of materials produced by the communities that they serve. These non-profit media collectives were imagined as a distributed network of organizations supporting the production, exhibition and study of media; serving as information centers about media resources; and supporting regional preservation efforts. However, media arts centers have remained over-looked and unexplored by the archival field. This dissertation seeks to shift this balance, including these artist-run organizations as part of the network of archives and collecting institutions preserving independent media. -

Subsidiarity and Proportionality in the Single Market

Subsidiarity and Proportionality in the Single Market An EU fit for inclusive growth Subsidiarity and Proportionality in the Single Market An EU fit for inclusive growth Imprint © 2018 Bertelsmann Stiftung Authors: Editing: Sigurd Naess-Schmidt David Gow Jonas Bjarke Jensen Graphs and figures: Copenhagen Economics Dietlind Ehlers Langebrogade 1 (entrance B3) DK-1411 Copenhagen Layout: Denmark Sabine Feige Project team: Title image: Dr. Dominic Ponattu (principal) Hans/pixabay.com - CC0, Public Domain, Dr. Katharina Gnath https://creativecommons.org/publicdo- Prof. Dr. Christian Kastrop main/zero/1.0/legalcode Dr. Marcus Wortmann Bertelsmann Stiftung Programme Europe’s Future Carl-Bertelsmann-Str. 256 33311 Gütersloh Germany Subsidiarity and Proportionality in the Single Market | Page 3 Preface The principles of subsidiarity and proportionality have been subject to intense debate. Which policy issues are best dealt with by central decision making at EU level, and which are best handled at member state level? This question takes on particular prominence when it comes to one of the EU’s cornerstones: the Single Market. While there has been a broad consensus on the economic benefits of free movement of labour, capital, goods and ser- vices, there are concerns about unnecessary regulation that fails to take local structures sufficiently into account. The Austrian government has made this a key point during its presidency of the Council of the EU in the second half of 2018. Bertelsmann Stiftung and Copenhagen Economics are here contributing to this debate with a study on the eco- nomic case for subsidiarity and proportionality in the EU. This report has been presented at the Presidency’s conference "Subsidiarity as a building principle of the European Union" in November 2018. -

“Building Resilience” a Comparison of Eight OECD Countries

Inclusive Growth for Germany | 12 “Building Resilience” A comparison of eight OECD countries “Building Resilience” A comparison of eight OECD countries Authors: Christoph Harendt Friedrich Heinemann July 2017 “Building Resilience” – Performance To Date Abstract Increasing resilience is one of the top priorities of global Crisis resilience in Germany economic policy. In a comparison of eight industrial- ized countries, a quite varied picture emerges. On four dimensions of performance (growth, unemployment, GDP protection against poverty and distribution), Japan and 100 Australia show considerable resilience in the context 80 of crisis. France and Italy demonstrate a low level of 60 resilience. The United States does little to serve as a role 40 model for Europe with regard to resilience; while growth At- Unem- 20 rates have been successfully stabilized there, crises have risk-of- ploy- poverty- ment been accompanied by increases in inequality. rate rate The figure examines Germany’s performance in the context of crisis. Performance is measured using a pre- and post-crisis comparison. In comparison to the aver- age of the here considered countries, Germany has coped Gini with crises well with regard to consequences for distri- coefficient bution and unemployment. The consequences of a crisis with regard to poverty risks correspond with the coun- Germany Average of countries try-sample average. In past decades, Germany has per- Source: Own calculations based on OECD data. High values within each of the various dimensions formed somewhat below the average level with regard to indicate a high degree of resilience stabilizing growth. However, this improved significantly to export-sector crises. with the financial crisis. -

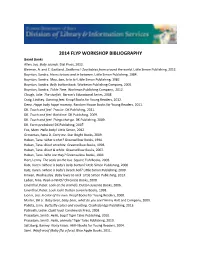

2014 FLYP WORKSHOP BIBLIOGRAPHY Board Books Allen, Joy

2014 FLYP WORKSHOP BIBLIOGRAPHY Board Books Allen, Joy. Baby sounds. Dial Press, 2012. Bleiman, A. and C. Eastland. ZooBorns!: Zoo babies from around the world. Little Simon Publishing, 2012. Boynton, Sandra. Horns to toes and in between. Little Simon Publishing, 1984. Boynton, Sandra. Moo, baa, la la la! Little Simon Publishing, 1982. Boynton, Sandra. Belly button book. Workman Publishing Company, 2005. Boynton, Sandra. Tickle Time. Workman Publishing Company, 2012. Clough, Julie. The starfish. Barron's Educational Series, 2008. Craig, Lindsey. Dancing feet. Knopf Books for Young Readers, 2012. Dena. Happi baby happi mommy. Random House Books for Young Readers, 2011. DK. Touch and feel: Tractor. DK Publishing, 2011. DK. Touch and feel: Bathtime. DK Publishing, 2009. DK. Touch and feel: Things that go. DK Publishing, 2009. DK. Farm peekaboo! DK Publishing, 2007. Fox, Mem. Hello baby! Little Simon, 2012. Grossman, Rena D. Carry me. Star Bright Books, 2009. Hoban, Tana. What is that? Greenwillow Books, 1994. Hoban, Tana. Black on white. Greenwillow Books, 1993. Hoban, Tana. Black & white. Greenwillow Books, 2007. Hoban, Tana. Who are they? Greenwillow Books, 1994. Hort, Lenny. The seals on the bus. Square Fish Books, 2003. Katz, Karen. Where is baby’s belly button? Little Simon Publishing, 2000. Katz, Karen. Where is baby’s beach ball? Little Simon Publishing, 2009. Kirwan, Wednesday. Baby loves to rock. Little Simon Publishing, 2013. Laden, Nina. Peek-a-WHO? Chronicle Books, 2000. Linenthal, Peter. Look at the animals. Dutton Juvenile Books, 2006. Linenthal, Peter. Look look! Dutton Juvenile Books, 1998. Lionni, Leo. A color of his own. Knopf Books for Young Readers, 2000. -

The Two-Way Immersion Toolkit

The Two-Way Immersion Toolkit Elizabeth Howard, Julie Sugarman, Marleny Perdomo, and Carolyn Temple Adger ������������������������������������������ ������������������������������������������ ������������������������������������������ Since 1975, The Education Alliance, a department at Brown University, has helped the education community improve schooling for our children. We conduct applied research and evaluation, and provide technical assistance and informational resources to connect research and practice, build knowledge and skills, and meet critical needs in the fi eld. With offi ces in Rhode Island, New York, Puerto Rico, and the Virgin Islands, and a dedicated team of over 100 skilled professionals, we provide services and resources to K-16 institutions across the country and beyond. As we work with educators, we customize our programs to the specifi c needs of our clients. Northeast and Islands Regional Educational Laboratory (LAB) The Education Alliance at Brown University is home to the Northeast and Islands Regional Educational Laboratory (LAB), one of ten educational laboratories funded by the U.S. Department of Education’s Institute of Education Sciences. Our goals are to improve teaching and learning, advance school improvement, build capacity for reform, and develop strategic alliances with key members of the region’s education and policymaking community. The LAB develops educational products and services for school administrators, policymakers, teachers, and parents in New England, New York, Puerto Rico, and the Virgin Islands. -

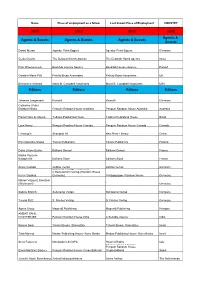

2019 2019 2019 2019 Agents & Scouts Agents & Scouts Agents

Name Place of employment as a fellow Last known Place of Employment COUNTRY 2019 2019 2019 2019 Agents & Agents & Scouts Agents & Scouts Agents & Scouts Scouts Daniel Mursa Agentur Petra Eggers Agentur Petra Eggers Germany Geula Geurts The Deborah Harris Agency The Deborah Harris Agency Israel Piotr Wawrzenczyk Book/lab Literary Agency Book/lab Literary Agency Poland Caroline Mann Plitt Felicity Bryan Associates Felicity Bryan Associates UK Beniamino Ambrosi Maria B. Campbell Associates Maria B. Campbell Associates USA Editors Editors Editors Editors Johanna Langmaack Rowohlt Rowohlt Germany Catherine (Cate) Elizabeth Blake Penguin Random House Australia Penguin Random House Australia Australia Flavio Rosa de Moura Todavia Publishing House Todavia Publishing House Brazil Lynn Henry Penguin Random House Canada Penguin Random House Canada Canada Li Kangqin Shanghai 99 New River Literary China Päivi Koivisto-Alanko Tammi Publishers Tammi Publishers Finland Dana Liliane Burlac Éditions Denoël Éditions Denoël France Maÿlis Vauterin- Bacqueville Editions Stock Editions Stock France Anvar Cukoski Aufbau Verlag Aufbau Verlag Germany Deutsche Verlags-Anstalt and C.Bertelsmann Verlag (Random House Karen Guddas Germany) Verlagsgruppe Random House Germany Marion Vazquez Boerzsei (Wichmann) ` ` Germany Sabine Erbrich Suhrkamp Verlag Suhrkamp Verlag Germany Teresa Pütz S. Fischer Verlag S. Fischer Verlag Germany Ágnes Orzóy Magvető Publishing Magvető Publishing Hungary AMBAR SAHIL CHATTERJEE Penguin Random House India A Suitable Agency India Ronnie -

Social Justice in the EU – Index Report 2017 Social Inclusion Monitor Europe

Social Justice in the EU – Index Report 2017 Social Inclusion Monitor Europe Daniel Schraad-Tischler, Christof Schiller, Sascha Matthias Heller, Nina Siemer EU Social Justice Index 2017 1 Denmark 7.39 2 Sweden 7.31 3 Finland 7.14 4 Czech Republic 6.84 5 Slovenia 6.74 6 Netherlands 6.73 7 Germany 6.71 8 Austria 6.69 9 Luxembourg 6.55 10 France 6.29 11 United Kingdom 6.22 12 Estonia 6.19 13 Belgium 6.18 14 Slovakia 5.91 EU Average 5.85 15 Poland 5.79 Malta 5.79 17 Ireland 5.66 18 Lithuania 5.61 19 Latvia 5.46 20 Portugal 5.36 21 Cyprus 5.31 22 Hungary 5.18 23 Croatia 5.07 24 Spain 4.96 25 Italy 4.84 26 Bulgaria 4.19 27 Romania 3.99 28 Greece 3.70 Social Justice Index Austria Belgium Bulgaria Croatia I 6.70 I 6.06 I 1.39 I 4.21 II 6.33 II 6.19 II 6.23 II 6.91 III 7.06 III 6.02 III 5.44 III 4.35 IV 6.72 IV 6.41 IV 4.02 IV 4.85 V 7.22 V 7.64 V 5.20 V 6.00 I Poverty prevention VI 6.10 VI 5.12 VI 5.20 VI 4.72 II Equitable education 0 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 0 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 0 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 0 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 III Labor market access France Germany Greece Hungary I 6.65 I 6.29 I 2.53 I 4.73 IV Social cohesion and II 5.93 II 6.54 II 5.27 II 5.20 non-discrimination III 5.90 III 7.21 III 3.46 III 6.33 IV 6.20 IV 6.97 IV 4.36 IV 4.48 V Health V 7.50 V 8.05 V 3.99 V 5.33 VI Intergenerational justice VI 5.59 VI 5.69 VI 3.60 VI 4.72 0 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 0 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 0 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 0 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 Malta Netherlands Poland Portugal Romania I 6.20 I 6.98 I 5.77 I 5.01 I 1.77 II 4.54 II 6.09 II 6.86 II 4.92 II 4.91 III 6.46 III 6.82 III 5.85 III 5.97 III 5.50 IV 4.89 IV 7.53 IV 5.77 IV 5.86 IV 4.33 V 7.66 V 7.70 V 4.69 V 6.04 V 4.21 VI 4.73 VI 5.27 VI 4.73 VI 4.89 VI 5.18 0 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 0 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 0 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 0 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 0 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 Annotation: Scores on a scale from 1 to 10. -

Required Reading List

Required Reading List Books are available at the MS Library Commission or the CPM Library. If no location is listed, you will have to acquire the book with your own resources. Please refer the Required Reading Abstract for further information about your reading projects. Contacts: MS Library Commission CSM Program CPM Program Curtis Sene Chatman Tori Whitley Shondra Houseworth 601-432-4127 601-359-2768 601-359-2715 [email protected] [email protected] [email protected] Book Title Author(s) Publisher Year of Location Publication The Accountable Organization: Reclaiming Integrity and John Marchica Davies-Black 2004 CPM Library Restoring Trust The Age of Speed Vince Poscente Bard Press 2008 CPM Library Becoming a Conflict Competent Leader Tim A. Flanagan Jossey-Bass 2007 CPM Library Craig E. Runde Benchmarking: for Best Practices in the Public Sector: Patricia Keehley Jossey-Bass 1997 CPM Library Achieving Performance Breakthrough in Federal State, and Local Agencies Breaking through Bureaucracy: A New Vision for Managing Michael Barzelay University of 1992 CPM Library in California Press Government Cigars, Whiskey, and Winning: Leadership Lesson from Al Kaltmen Prentice Hall Press 1998 CPM Library General Ulysses S. Grant Coaching for Commitment: Managerial Strategies for Dennis Kinlaw Pfeiffer 1989 CPM Library Obtaining Superior Performance The Complete Communicator: Change Your Communication, William Lampton Hillsboro Press 1999 CPM Library Change Your Life! Crisis Management: Planning for the Inevitable Steven Fink American Manage. 1986 CPM Library Association Crucial Confrontations Kerry Patterson McGraw-Hill 2002 CPM Library Joseph Grenny Crucial Conversations Kerry Patterson McGraw-Hill 2002 CPM Library Joseph Grenny The Dream Manager Matthew Kelly Beacon Publishing 2007 CPM Library Patrick M. -

Books for Peace: an Annotated Bibliography

24 MONTESSORI LIFE BOOKS FOR PEACE: AN ANNOTATED BIBLIOGRAPHY By Ruth van Veenendaal, MEd Books for children can be among the most beautiful creations by artists today: Colorful and in- viting, they can range from simple to complex and often intend to teach or illustrate a concept. The subject matter is as broad as the collective imagination. One area of focus that is receiving needed attention in the world of books is education for peace. Since its formation, the AMS Peace Committee has had education for peace as its mission. Essential aids in this process, after the direction of the prepared guide, are books that exemplify peaceful living. Ruth van Veenendaal, a longtime member of the Peace Committee, has compiled an exten- sive list of peace books currently available. The list is divided by suggested age levels, with a short summary of each book’s contents. It is a wealth of information for busy educators who want to promote peace through reading! —Julie Winnette PHOTOGRAPHY © BY BILL SALLANS SPRING 2016 25 FOR EARLY CHILDHOOD Hands Are Not for Hitting All I See Is Part of Me Agassi, M. (2009). Free Spirit Publishing. Curtis, C. M. (1994). Illumination Arts Publishing Company. Ages 4–7. Ages 4+. Children learn that violence is never A child discovers his connections with all of life. acceptable. And to Think That We Thought That We’d Never Be Friends! I Offer You Peace Hoberman, M. A., and Hawkes, K. (2003). Dragonfly Books. Wolf, A. D. (2001). Parent Child Press. Ages 5–8. Ages 3–7. “I offer you peace.