Journal of Learning Disabilities

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

I'm Empowered

2018 ANNUAL RePORT I’M EMPOWERED ENLIGHTENING WAYS to LIVE WITH Low VISION Regardless of where you are on the vision spectrum, Braille Institute provides comprehensive services to address the various needs of individuals who have a visual impairment. “We are here to help any individual who is having difficulties or struggling to participate in daily activities because of low vision. We’re not just for individuals who are totally blind,” said Nilima Tanna, Director of Low Vision Services (right). A person’s first introduction to Braille Institute’s services can be through our free low vision consultation with a specialist. In a typical one hour consultation, the specialist assesses and learns what activities the client is struggling with, and helps them find different ways of achieving their objectives. “We came to Braille Institute for a magnifier, but we left with so much more!” Carrie, whose mother has Macular Degeneration, said. “My only regret is that we didn’t meet Nilima two years ago when my mom’s vision first changed so drastically.” Carrie’s mother, Barbara, learned how to change the settings on her computer, received tips for writing a check, was told including magnification devices to help them how to visually mark the settings on her washer and dryer, and reach their goals,” Nilima said. learned she could request large print medication labels from Carrie said she saw her mother more her pharmacist. encouraged than at any other time in the “We assess their ability to perform various activities, last few years after having her one-on-one educate them about things such as how lighting and contrast consultation. -

Hooray for Health Arthur Curriculum

Reviewed by the American Academy of Pediatrics HHoooorraayy ffoorr HHeeaalltthh!! Open Wide! Head Lice Advice Eat Well. Stay Fit. Dealing with Feelings All About Asthma A Health Curriculum for Children IS PR O V IDE D B Y FUN D ING F O R ARTHUR Dear Educator: Libby’s® Juicy Juice® has been a proud sponsor of the award-winning PBS series ARTHUR® since its debut in 1996. Like ARTHUR, Libby’s Juicy Juice, premium 100% juice, is wholesome and loved by kids. Promoting good health has always been a priority for us and Juicy Juice can be a healthy part of any child’s balanced diet. Because we share the same commitment to helping children develop and maintain healthy lives, we applaud the efforts of PBS in producing quality educational television. Libby’s Juicy Juice hopes this health curriculum will be a valuable resource for teaching children how to eat well and stay healthy. Enjoy! Libby’s Juicy Juice ARTHUR Health Curriculum Contents Eat Well. Stay Fit.. 2 Open Wide! . 7 Dealing with Feelings . 12 Head Lice Advice . 17 All About Asthma . 22 Classroom Reproducibles. 30 Taping ARTHUR™ Shows . 32 ARTHUR Home Videos. 32 ARTHUR on the Web . 32 About This Guide Hooray for Health! is a health curriculum activity guide designed for teachers, after-school providers, and school nurses. It was developed by a team of health experts and early childhood educators. ARTHUR characters introduce five units exploring five distinct early childhood health themes: good nutrition and exercise (Eat Well. Stay Fit.), dental health (Open Wide!), emotions (Dealing with Feelings), head lice (Head Lice Advice), and asthma (All About Asthma). -

Kids with Asthma Can! an ACTIVITY BOOKLET for PARENTS and KIDS

Kids with Asthma Can! AN ACTIVITY BOOKLET FOR PARENTS AND KIDS Kids with asthma can be healthy and active, just like me! Look inside for a story, activity, and tips. Funding for this booklet provided by MUSEUMS, LIBRARIES AND PUBLIC BROADCASTERS JOINING FORCES, CREATING VALUE A Corporation for Public Broadcasting and Institute of Museum and Library Services leadership initiative PRESENTED BY Dear Parents and Friends, These days, almost everybody knows a child who has asthma. On the PBS television show ARTHUR, even Arthur knows someone with asthma. It’s his best friend Buster! We are committed to helping Boston families get the asthma care they need. More and more children in Boston these days have asthma. For many reasons, children in cities are at extra risk of asthma problems. The good news is that it can be kept under control. And when that happens, children with asthma can do all the things they like to do. It just takes good asthma management. This means being under a doctor’s care and taking daily medicine to prevent asthma Watch symptoms from starting. Children with asthma can also take ARTHUR ® quick relief medicine when asthma symptoms begin. on PBS KIDS Staying active to build strong lungs is a part of good asthma GO! management. Avoiding dust, tobacco smoke, car fumes, and other things that can start an asthma attack is important too. We hope this booklet can help the children you love stay active with asthma. Sincerely, 2 Buster’s Breathless Adapted from the A RTHUR PBS Series A Read-Aloud uster and Arthur are in the tree house, reading some Story for B dusty old joke books they found in Arthur’s basement. -

Iowa Dyslexia Task Force Executive Summary

Dyslexia Task Force Report Iowa Dyslexia Task Force Executive Summary i November 15, 2019 Dyslexia Task Force Report Iowa Dyslexia Task Force Task Force Chair Person David Tilly, Iowa Department of Education Members Lonna Anderson, Ottumwa Community School District Helen Blitvich, Decoding Dyslexia Amy L Conrad, University of Iowa Psychologist Susan Etscheidt, University of Northern Iowa Katie Greving, Decoding Dyslexia Elizabeth Hoksbergen, Apples of Gold Center for Learning, Inc. Erin Klopstad, Nevada Community School District Cindy Lewis, Pleasant Valley Community School District Nina Lorimor-Easley, True Potential Education Kristin Orton, Heartland Area Education Agency Deborah Reed, Iowa Reading Research Center Kim Schmidt, Odebolt Arthur Battle Creek Ida Grove Community School District For More Information Inquiries or questions about the Task Force report should be directed to one of the following Task Force members: Katie Greving Email: [email protected] Nina Lorimor-Easley Email: [email protected] Kristin Orton Email: [email protected] ii Dyslexia Task Force Report Executive Summary The Iowa Dyslexia Task Force calls for stakeholders across the state to take immediate and transformative action to support students with characteristics of dyslexia, their families, and their teachers. The Task Force brought together a diverse group of K-12 teachers and school leaders, higher education faculty, professionals in diagnosing and supporting students with dyslexia, parents of children with dyslexia, and individuals with dyslexia themselves. As a team, we spent a year researching and debating to arrive at the conclusions and recommendations in this report. Right now, in Iowa there are not enough educators in our schools who understand dyslexia and have the skills and knowledge to support students with characteristics of dyslexia. -

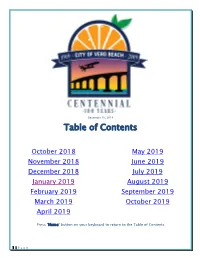

Table of Contents

December 10, 2018 Table of Contents October 2018 May 2019 November 2018 June 2019 December 2018 July 2019 January 2019 August 2019 February 2019 September 2019 March 2019 October 2019 April 2019 Press "Home" button on your keyboard to return to the Table of Contents 1 | P a g e The City of Vero Beach Centennial Year Calendar (October 2018-October 2019) Centennial Presenting Sponsor Florida Power & Light Visit website: www.VeroBeach100.org Can also use .net and .com ~ Event times, dates, locations and descriptions are subject to change ~ October 2018 Monthly Sponsor: White Glove Moving Monday, October 1, 2018 Walking Tree Centennial Brew A Pale Ale brewed with hibiscus and Centennial hops (YUM!) has been developed and distributed by Walking Tree Brewery all along the Treasure Coast… so everyone should look for it in their favorite bars and restaurants! The winner of their summertime naming contest…“Your Town. Your Beer. YOU Name It!” has not been determined as of this writing (6/18). Amanda Saunders, 772-360-6956, [email protected] Friday & Saturday, October 5 & 6, 2018 McKee Botanical Garden Come and enjoy a $1 Admission Community Centennial Appreciation Day at McKee, thanking the community for their support since the original McKee Jungle Gardens opened in 1932. Who could ask for a better way to spend a beautiful fall day walking through the grounds of this extraordinary Vero Beach Sanctuary. Connie Cotherman - [email protected] Tuesday, October 16, 2018 3pm Sunbonnet Sue Quilters Guild Representatives of the Sunbonnet Sue Quilters Guild designed and created a quilt in recognition of the Centennial Year. -

Roanoke County Police Department Outstanding Warrants List As of 08

Roanoke County Police Department Outstanding Warrants List as of 09/20/2021 Press the Ctrl, F keys to search by Last Name with Adobe Acrobat Reader's search feature or just scroll through the document. Name Sex Age Warrant Charge A Acros Lopez, Julio CeserMale 30 Felony By Prisoner Adams, Benjamin EarlMale 32 Fail To Appear On Misdemeanor Charge Adams, Jacqueline AFemale 37 Contributing To The Delinquency Of A Minor Adams, Jacqueline AFemale 37 False Report Of Crime To Police Aker, Ruthie Age Of Children Required To Attend School Albright, Katherine ElizabethFemale 30 Order Of Protection (Final) Aliff, James MaxwellMale 31 Revocation Of Suspension Of Sentence/Probation Alouf, Hollie HarrisFemale 49 Zoning Violation Al-Tamimi, Yassin KamelMale 21 Reckless Driving - General Amos, Tommie LeeMale 50 Order Of Protection (Final) Anderson, Chris AaronMale 30 Violation Of Stalking Protective Order Anderson, Rodney WestonMale 59 Contempt Of Court: Misbehavior In Court Andrew, Richard DavidMale 33 Possess, Transport Firearms, Ammunitions, Explosives By Convicted Felons Andrew, Richard DavidMale 33 Destruction Of Property, Monument <$1000 W/Int Andrew, Richard DavidMale 33 Credit Card Theft - From Building Andrew, Richard DavidMale 33 Assault & Battery -Family Member Andrew, Richard DavidMale 33 Petit Larceny: Building <$1000 Andrew, Richard DavidMale 33 Simple - Assault By Strangulation Argueta, Enso NoelMale 34 Fail To Appear On Misdemeanor Charge Armstrong, Sandra KayFemale 58 Fail To Appear On Misdemeanor Charge Arrington, Crystina JasmineFemale -

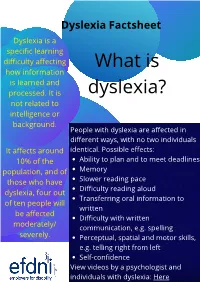

Dyslexia Is a Specific Learning Difficulty Affecting How Information Is

Dyslexia Factsheet Dyslexia is a specific learning difficulty affecting What is how information is learned and processed. It is dyslexia? not related to intelligence or background. People with dyslexia are affected in different ways, with no two individuals It affects around identical. Possible effects: 10% of the Ability to plan and to meet deadlines population, and of Memory those who have Slower reading pace Difficulty reading aloud dyslexia, four out Transferring oral information to of ten people will written be affected Difficulty with written moderately/ communication, e.g. spelling severely. Perceptual, spatial and motor skills, e.g. telling right from left Self-confidence View videos by a psychologist and individuals with dyslexia: Here Dyslexia and some of its effects: What some people with dyslexia say: “I have the right ideas but I can’t put it down on paper” "I have loads of ideas racing round my head” “I can’t take in what is being said to me” “When I read, the words jump from the page” “I was always told I was stupid at school” Some people with dyslexia see this when they read: Some people with dyslexia see this: Whilereadingdisorientationcancauseapersonwithdyslexia toperceivethewordsonapagestrungtogetherwithnospaces makingitimpossibletodecipherwordswithinasentence.Asd isorirentationincreasestheworsedisorientationbecomes. NB: These effects can increase with fatigue, and can cause headaches, eye ache and disorientation. Positive Effects According to the British Dyslexia Association, “It is important to remember that there are positives to thinking differently. Many dyslexic people show strengths in areas such as reasoning and in visual and creative fields.” Some positive effects: Highly creative Intuitive Can excel at hands-on practical tasks Three-dimensional problem-solving Did you know that these people have dyslexia? Making adjustments Making adjustments which are tailored to each person’s abilities and challenges is vital to ensure that every individual can reach their potential. -

Arthur WN Guide Pdfs.8/25

Building Global and Cultural Awareness Keep checking the ARTHUR Web site for new games with the Dear Educator: World Neighborhood ® ® has been a proud sponsor of the Libby’s Juicy Juice ® theme. RTHUR since its debut in award-winning PBS series A ium 100% 1996. Like Arthur, Libby’s Juicy Juice, prem juice, is wholesome and loved by kids. itment to a RTHUR’s comm Libby’s Juicy Juice shares A world in which all children and cultures are appreciated. We applaud the efforts of PBS in producingArthur’s quality W orld educational television and hope that Neighborhood will be a valuable resource for teaching children to understand and reach out to one another. Enjoy! Libby’s Juicy Juice Contents About This Guide. 1 Around the Block . 2 Examine diversity within your community Around the World. 6 Everyday Life in Many Cultures: An overview of world diversity Delve Deeper: Explore a specific culture Dear Pen Pal . 10 Build personal connections through a pen pal exchange More Curriculum Connections . 14 Infuse your curriculum with global and cultural awareness Reflections . 15 Reflect on and share what you have learned Resources . 16 All characters and underlying materials (including artwork) copyright by Marc Brown.Arthur, D.W., and the other Marc Brown characters are trademarks of Marc Brown. About This Guide As children reach the early elementary years, their “neighborhood” expands beyond family and friends, and they become aware of a larger, more diverse “We live in a world in world. How are they similar and different from others? What do those which we need to share differences mean? Developmentally, this is an ideal time for teachers and providers to join children in exploring these questions. -

Run Date: 08/30/21 12Th District Court Page

RUN DATE: 09/27/21 12TH DISTRICT COURT PAGE: 1 312 S. JACKSON STREET JACKSON MI 49201 OUTSTANDING WARRANTS DATE STATUS -WRNT WARRANT DT NAME CUR CHARGE C/M/F DOB 5/15/2018 ABBAS MIAN/ZAHEE OVER CMV V C 1/01/1961 9/03/2021 ABBEY STEVEN/JOH TEL/HARASS M 7/09/1990 9/11/2020 ABBOTT JESSICA/MA CS USE NAR M 3/03/1983 11/06/2020 ABDULLAH ASANI/HASA DIST. PEAC M 11/04/1998 12/04/2020 ABDULLAH ASANI/HASA HOME INV 2 F 11/04/1998 11/06/2020 ABDULLAH ASANI/HASA DRUG PARAP M 11/04/1998 11/06/2020 ABDULLAH ASANI/HASA TRESPASSIN M 11/04/1998 10/20/2017 ABERNATHY DAMIAN/DEN CITYDOMEST M 1/23/1990 8/23/2021 ABREGO JAIME/SANT SPD 1-5 OV C 8/23/1993 8/23/2021 ABREGO JAIME/SANT IMPR PLATE M 8/23/1993 2/16/2021 ABSTON CHERICE/KI SUSPEND OP M 9/06/1968 2/16/2021 ABSTON CHERICE/KI NO PROOF I C 9/06/1968 2/16/2021 ABSTON CHERICE/KI SUSPEND OP M 9/06/1968 2/16/2021 ABSTON CHERICE/KI NO PROOF I C 9/06/1968 2/16/2021 ABSTON CHERICE/KI SUSPEND OP M 9/06/1968 8/04/2021 ABSTON CHERICE/KI OPERATING M 9/06/1968 2/16/2021 ABSTON CHERICE/KI REGISTRATI C 9/06/1968 8/09/2021 ABSTON TYLER/RENA DRUGPARAPH M 7/16/1988 8/09/2021 ABSTON TYLER/RENA OPERATING M 7/16/1988 8/09/2021 ABSTON TYLER/RENA OPERATING M 7/16/1988 8/09/2021 ABSTON TYLER/RENA USE MARIJ M 7/16/1988 8/09/2021 ABSTON TYLER/RENA OWPD M 7/16/1988 8/09/2021 ABSTON TYLER/RENA SUSPEND OP M 7/16/1988 8/09/2021 ABSTON TYLER/RENA IMPR PLATE M 7/16/1988 8/09/2021 ABSTON TYLER/RENA SEAT BELT C 7/16/1988 8/09/2021 ABSTON TYLER/RENA SUSPEND OP M 7/16/1988 8/09/2021 ABSTON TYLER/RENA SUSPEND OP M 7/16/1988 8/09/2021 ABSTON -

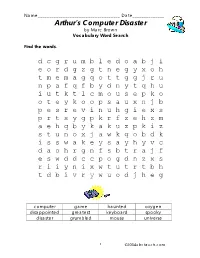

Arthur's Computer Disaster

Name____________________________________ Date______________ Arthur’s Computer Disaster by Marc Brown Vocabulary Word Search Find the words. d c g r u m b l e d o a b j i e o r d g z g t n e g y x o h t m e m a g q o t t g g j r u n p a f q f b y d n y t q h u i u t k t l c m o u s e p k o o t e y k o o p s a u x n j b p e s r e v i n u h g i e x s p r t s y g p k r f z e h z m a e h q b y k a k u z p k i z s t u n o x j a w k q o b d k i s s w a k e y s a y h y v c d a o h r g n f s b t r a j f e s w d d c c p o g d n z x s r i i y n i x w t u t r t b h t d b i v r y w u o d j h e g computer game haunted oxygen disappointed greatest keyboard spooky disaster grumbled mouse universe 1 ©2004abcteach.com Name____________________________________ Date______________ Arthur’s Computer Disaster by Marc Brown Crossword Puzzle Complete the puzzle. -

United Way of Greater Milwaukee & Waukesha County Hosts

For Immediate Release For more information, contact Rebecca Schimke, Communications Specialist [email protected] 414.263.8125 (O), 414.704.8879 (C) United Way of Greater Milwaukee & Waukesha County Hosts Children’s Writer & Illustrator of Arthur Adventure Series, Marc Brown, to Promote Childhood Literacy Reading Blitz Day also celebrated Reader, Tutor, Mentor Volunteers. MILWAUKEE [March 25, 2015] – United Way of Greater Milwaukee & Waukesha County hosted a Reading Blitz Day to celebrate a 3-year effort of recruiting and placing 4,800+ reader, tutor, and mentor volunteers throughout Greater Milwaukee. The importance of reading to kids cannot be overstated. “Once children start school, difficulty with reading contributes to school failure, which can increase the risk of absenteeism, leaving school, juvenile delinquency, substance abuse, and teenage pregnancy - all of which can perpetuate the cycles of poverty and dependency.” according to the non-profit organization, Reach Out & Read. “United Way recognizes that caring adults working with children of all ages has the power to boost academic achievement and set them on the track for success,” said Karissa Gretebeck, marketing and community engagement specialist, United Way of Greater Milwaukee & Waukesha County. “We are thankful for the agency partners, other non-profits and schools who partnered with us to make this possible.” United Way also organized a book drive leading up to the day. New or gently used books were collected at 13 Milwaukee Public Library locations, Brookfield Public Library, Muskego Public Library and Martha Merrell’s Books in downtown Waukesha. Books from the drive will be donated to United Way funded partner agencies that were a part of the Reader, Tutor, Mentor effort. -

Arthur's TV Trouble Work Page and Key FREE

Arthur's TV Trouble Name ___________________ Date __________ Read the book and answer the questions. When did Arthur begin to want to buy an amazing Treat Timer? ________________________________________________________ Why did Arthur want to buy it? ________________________________________________________________ Do you think Pal really needed a Treat Timer? Why or why not? ________________________________________________________________ How much money did Arthur have, even with all his birthday money? ________________________________________________________________ How much more money did he need to buy a Treat Timer? ________________________________________________________________ Why did Arthur have to retake the spelling test? ________________________________________________________________ What job did he do to earn money to buy the Treat Timer? ________________________________________________________________ Why do you think D.W. said Arthur was nicer when he was rich? ________________________________________________________________ How long did it take Arthur to assemble the Treat Timer? ________________________________________________________________ Did Arthur learn a lesson? Why or why not? ________________________________________________________________ Arthur's TV Trouble -- Teacher Answer Key 1. When did Arthur begin to want to buy an amazing Treat Timer? He thought it would be cool for his dog, Pal. 2. Why did Arthur want to buy it? He was fooled by the commercial (or just he saw a commercial) 3. Do you think Pal really needed a Treat Timer? Why or why not? Answers may vary, and any opinion is OK supported by a reason 4. How much money did Arthur have, even with all his birthday money? Ten dollars and three cents, or $10.03 5. How much more money did he need to buy a Treat Timer? $9.92 6. Why did Arthur have to retake the spelling test? He was daydreaming about the Treat Timer and didn't listen.