The Provinces

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Advancing Workers' Rights Under Sdgs

Research Paper IX Advancing Workers’ Rights under SDGs Policy and Situational Analysis of Decent Work in Nepal The Centre for the Study of Labour and Mobility is a research centre within Social Science Baha, Kathmandu, set up with the primary objective of contributing to broader theories and understandings on labour and mobility. It conducts interdisciplinary, policy-relevant research on critical issues affecting working people; serves as a forum to foster academic, policy and public debates; and provides new insights on the impact of labour and migration. Jeevan Baniya with 9 789937934916 Sunita Basnet, Himalaya Kharel and Rajita Dhungana Research Paper IX Advancing Workers’ Rights under SDGs Policy and Situational Analysis of Decent Work in Nepal Jeevan Baniya with Sunita Basnet, Himalaya Kharel and Rajita Dhungana This publication was made possible through the financial support of the Solidarity Center, Washington DC. The authors would like to thank Krishma Sharma of the Solidarity Center for administrative and logistical support during the study. The authors are grateful to Saloman Rajbanshi, Senior Programme Officer and Dr Biswo Poudel, Economic Advisor, from ILO Country Office Nepal, for reviewing the report and providing their valuable feedback. The authors would also like to thank Khem Shreesh at Social Science Baha for his feedback while finalising this publication. © Solidarity Center, 2019 ISBN: 978 9937 9349 1 6 Centre for the Study of Labour and Mobility Social Science Baha 345 Ramchandra Marg, Battisputali, Kathmandu – 9, Nepal Tel: +977-1-4472807, 4480091 • Fax: +977-1-4475215 [email protected] • www.ceslam.org Printed in Nepal CONTENTS Acronyms v Executive Summary vii 1. -

Nepal Human Rights Year Book 2021 (ENGLISH EDITION) (This Report Covers the Period - January to December 2020)

Nepal Human Rights Year Book 2021 (ENGLISH EDITION) (This Report Covers the Period - January to December 2020) Editor-In-Chief Shree Ram Bajagain Editor Aarya Adhikari Editorial Team Govinda Prasad Tripathee Ramesh Prasad Timalsina Data Analyst Anuj KC Cover/Graphic Designer Gita Mali For Human Rights and Social Justice Informal Sector Service Centre (INSEC) Nagarjun Municipality-10, Syuchatar, Kathmandu POBox : 2726, Kathmandu, Nepal Tel: +977-1-5218770 Fax:+977-1-5218251 E-mail: [email protected] Website: www.insec.org.np; www.inseconline.org All materials published in this book may be used with due acknowledgement. First Edition 1000 Copies February 19, 2021 © Informal Sector Service Centre (INSEC) ISBN: 978-9937-9239-5-8 Printed at Dream Graphic Press Kathmandu Contents Acknowledgement Acronyms and Abbreviations Foreword CHAPTERS Chapter 1 Situation of Human Rights in 2020: Overall Assessment Accountability Towards Commitment 1 Review of the Social and Political Issues Raised in the Last 29 Years of Nepal Human Rights Year Book 25 Chapter 2 State and Human Rights Chapter 2.1 Judiciary 37 Chapter 2.2 Executive 47 Chapter 2.3 Legislature 57 Chapter 3 Study Report 3.1 Status of Implementation of the Labor Act at Tea Gardens of Province 1 69 3.2 Witchcraft, an Evil Practice: Continuation of Violence against Women 73 3.3 Natural Disasters in Sindhupalchok and Their Effects on Economic and Social Rights 78 3.4 Problems and Challenges of Sugarcane Farmers 82 3.5 Child Marriage and Violations of Child Rights in Karnali Province 88 36 Socio-economic -

![Wild Mammals of the Annapurna Conservation Area Cggk"0F{ ;+/If0f If]Qsf :Tgwf/L Jgohgt' Wild Mammals of the Annapurna Conservation Area - 2019](https://docslib.b-cdn.net/cover/7316/wild-mammals-of-the-annapurna-conservation-area-cggk-0f-if0f-if-qsf-tgwf-l-jgohgt-wild-mammals-of-the-annapurna-conservation-area-2019-127316.webp)

Wild Mammals of the Annapurna Conservation Area Cggk"0F{ ;+/If0f If]Qsf :Tgwf/L Jgohgt' Wild Mammals of the Annapurna Conservation Area - 2019

Wild Mammals of the Annapurna Conservation Area cGgk"0f{ ;+/If0f If]qsf :tgwf/L jGohGt' Wild Mammals of the Annapurna Conservation Area - 2019 ISBN 978-9937-8522-8-9978-9937-8522-8-9 9 789937 852289 National Trust for Nature Conservation Annapurna Conservation Area Project Khumaltar, Lalitpur, Nepal Hariyo Kharka, Pokhara, Kaski, Nepal National Trust for Nature Conservation P.O. Box: 3712, Kathmandu, Nepal P.O. Box: 183, Kaski, Nepal Tel: +977-1-5526571, 5526573, Fax: +977-1-5526570 Tel: +977-61-431102, 430802, Fax: +977-61-431203 Annapurna Conservation Area Project Email: [email protected] Email: [email protected] Website: www.ntnc.org.np Website: www.ntnc.org.np 2019 Wild Mammals of the Annapurna Conservation Area cGgk"0f{ ;+/If0f If]qsf :tgwf/L jGohGt' National Trust for Nature Conservation Annapurna Conservation Area Project 2019 Wild Mammals of the Annapurna Conservation Area cGgk"0f{ ;+/If0f If]qsf :tgwf/L jGohGt' Published by © NTNC-ACAP, 2019 All rights reserved Any reproduction in full or in part must mention the title and credit NTNC-ACAP. Reviewers Prof. Karan Bahadur Shah (Himalayan Nature), Dr. Naresh Subedi (NTNC, Khumaltar), Dr. Will Duckworth (IUCN) and Yadav Ghimirey (Friends of Nature, Nepal). Compilers Rishi Baral, Ashok Subedi and Shailendra Kumar Yadav Suggested Citation Baral R., Subedi A. & Yadav S.K. (Compilers), 2019. Wild Mammals of the Annapurna Conservation Area. National Trust for Nature Conservation, Annapurna Conservation Area Project, Pokhara, Nepal. First Edition : 700 Copies ISBN : 978-9937-8522-8-9 Front Cover : Yellow-bellied Weasel (Mustela kathiah), back cover: Orange- bellied Himalayan Squirrel (Dremomys lokriah). -

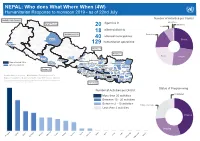

NEPAL: Who Does What Where When (4W)

NEPAL: Who does What Where When (4W) Humanitarian Response to monsoon 2019 - as of 22nd July Number of Activities per Cluster SudurPaschim Province Agencies in Education Karnali Province Nutrition 20 Health Darchula 18 affected districts Gandaki Province Protection affected municipalities Province 7 Province 6 Dolpa 40 Shelter humanitarian operations Kanchanpur 129 Kanchanpur Kailali Province 4 Province 3 Bardiya Gorkha Kaski Province 1 Rasuwa Food Banke Province 5 WASH Dang Tanahu Dhading Dang ProvinceKathmandu 3 Palpa KathmanduDhading Dolakha Most affected HHs Kathmandu KapilbastuKapilbastu Nawalparasi Kavrepalanchok Sankhuwasabha Rupandehi Chitawan Affected Districts MakwanpurMakwanpurLalitpurLalitpur Ramechhap ProvinceTaplejung 1 Okhaldhunga Province 5 Parsa SindhuliSindhuli Parsa Khotang Bhojpur Bara PanchtharPanchthar Sarlahi Rautahat Sarlahi Udayapur DhankutaBara Rautahat MahottariDhanusa Udayapur Ilam Creation date: 23 July 2019 Glide Number: FL-2019-000083-NPL Mahottari DhanusaSiraha Sunsari Sources: Nepal Survey Department, MoHA, Nepal HCT clusters - 22nd July Siraha SaptariSunsari Morang Jhapa The boundaries and names shown and the designations used on this map do not imply ocial Province 2 Saptari Morang Jhapa endorsement or acceptance by the United Nations. Province 2 Status of Programming Number of Activities per District Completed More than 20 activities Between 10 - 20 activities Between 2 - 10 activities Status unknown Less than 2 activities Planned On-going Bara Parsa Banke Kaski Kaski Sarlahi Siraha Morang Udayapur Saptari Sunsari Sindhuli Surkhet Rautahat Mahottari Dhanusa Kathmandu Makwanpur Early Grand District Education Health Nutrition WASH Shelter/NFI Logistic Food Protection Recovery Total Banke 1 1 Bara 1 1 Dhanusa 2 2 Kailai 1 1 Kaski 1 1 Kathmandu 1 1 Mahottari 1 2 2 7 12 Makwanpur 1 1 Morang 2 6 1 9 Parsa 1 1 2 Rautahat 1 8 5 6 8 28 Saptari 2 2 2 2 8 Sarlahi 1 4 2 9 4 20 Sindhuli 1 5 6 Siraha 1 4 1 5 2 13 Sunsari 1 1 5 7 Surkhet 0 1 0 0 1 Udayapur 1 1 5 2 9 N/A 1 3 1 1 6 Grand Total 1 10 1 31 36 0 29 21 0 129. -

Oli's Temple Visit Carries an Underlying Political Message, Leaders and Observers

WITHOUT F EAR OR FAVOUR Nepal’s largest selling English daily Vol XXVIII No. 329 | 8 pages | Rs.5 O O Printed simultaneously in Kathmandu, Biratnagar, Bharatpur and Nepalgunj 24.5 C -5.4 C Tuesday, January 26, 2021 | 13-10-2077 Dipayal Jumla Campaigners decry use of force by police on peaceful civic protest against the House dissolution move Unwarned, protesters were hit by water cannons and beaten up as they marched towards Baluwatar. Earlier in the day, rights activists were rounded up from same area. ANUP OJHA Dahayang Rai, among others, led the KATHMANDU, JAN 25 protest. But no sooner had the demonstra- The KP Sharma Oli administration’s tors reached close to Baluwatar, the intolerance of dissent and civil liberty official residence of Prime Minister was in full display on Monday. Police Oli, than police charged batons and on Monday afternoon brutally charged used water cannons to disperse them, members of civil society, who had in what was reminiscent of the days gathered under the umbrella of Brihat when protesters were assaulted dur- Nagarik Andolan, when they were ing the 2006 movement, which is marching towards Baluwatar to pro- dubbed the second Jana Andolan, the test against Oli’s decision to dissolve first being the 1990 movement. the House on December 20. The 1990 movement ushered in In a statement in the evening, democracy in the country and the sec- Brihat Nagarik Andolan said that the ond culminated in the abolition of government forcefully led the peaceful monarc h y. protest into a violent clash. In a video clip by photojournalist “The police intervention in a Narayan Maharjan of Setopati, an peaceful protest shows KP Sharma online news portal, Wagle is seen fall- Oli government’s fearful and ing down due to the force of the water suppressive mindset,” reads the cannon, and many others being bru- POST PHOTO: ANGAD DHAKAL statement. -

The Kamaiya System of Bonded Labour in Nepal

Nepal Case Study on Bonded Labour Final1 1 THE KAMAIYA SYSTEM OF BONDED LABOUR IN NEPAL INTRODUCTION The origin of the kamaiya system of bonded labour can be traced back to a kind of forced labour system that existed during the rule of the Lichhabi dynasty between 100 and 880 AD (Karki 2001:65). The system was re-enforced later during the reign of King Jayasthiti Malla of Kathmandu (1380–1395 AD), the person who legitimated the caste system in Nepali society (BLLF 1989:17; Bista 1991:38-39), when labourers used to be forcibly engaged in work relating to trade with Tibet and other neighbouring countries. In the 18th and 19th centuries, the Gorkhali and Rana rulers introduced and institutionalised new forms of forced labour systems such as Jhara,1 Hulak2, Beth3 and Begar4 (Regmi, 1972 reprint 1999:102, cited in Karki, 2001). The later two forms, which centred on agricultural works, soon evolved into such labour relationships where the workers became tied to the landlords being mortgaged in the same manner as land and other property. These workers overtimes became permanently bonded to the masters. The kamaiya system was first noticed by anthropologists in the 1960s (Robertson and Mishra, 1997), but it came to wider public attention only after the change of polity in 1990 due in major part to the work of a few non-government organisations. The 1990s can be credited as the decade of the freedom movement of kamaiyas. Full-scale involvement of NGOs, national as well as local, with some level of support by some political parties, in launching education classes for kamaiyas and organising them into their groups culminated in a kind of national movement in 2000. -

Gandaki Province

2020 PROVINCIAL PROFILES GANDAKI PROVINCE Surveillance, Point of Entry Risk Communication and and Rapid Response Community Engagement Operations Support Laboratory Capacity and Logistics Infection Prevention and Control & Partner Clinical Management Coordination Government of Nepal Ministry of Health and Population Contents Surveillance, Point of Entry 3 and Rapid Response Laboratory Capacity 11 Infection Prevention and 19 Control & Clinical Management Risk Communication and Community Engagement 25 Operations Support 29 and Logistics Partner Coordination 35 PROVINCIAL PROFILES: BAGMATI PROVINCE 3 1 SURVEILLANCE, POINT OF ENTRY AND RAPID RESPONSE 4 PROVINCIAL PROFILES: GANDAKI PROVINCE SURVEILLANCE, POINT OF ENTRY AND RAPID RESPONSE COVID-19: How things stand in Nepal’s provinces and the epidemiological significance 1 of the coronavirus disease 1.1 BACKGROUND incidence/prevalence of the cases, both as aggregate reported numbers The provincial epidemiological profile and population denominations. In is meant to provide a snapshot of the addition, some insights over evolving COVID-19 situation in Nepal. The major patterns—such as changes in age at parameters in this profile narrative are risk and proportion of females in total depicted in accompanying graphics, cases—were also captured, as were which consist of panels of posters the trends of Test Positivity Rates and that highlight the case burden, trend, distribution of symptom production, as geographic distribution and person- well as cases with comorbidity. related risk factors. 1.4 MAJOR Information 1.2 METHODOLOGY OBSERVATIONS AND was The major data sets for the COVID-19 TRENDS supplemented situation updates have been Nepal had very few cases of by active CICT obtained from laboratories that laboratory-confirmed COVID-19 till teams and conduct PCR tests. -

Understanding Children‟S Work in Nepal

Public Disclosure Authorized Public Disclosure Authorized July 2003 Understanding Children‟s Work Series in Nepal Report on child labour Country Report Public Disclosure Authorized Public Disclosure Authorized July 2003 Understanding Children’s Work Project Understanding children’s work in Nepal Country Report July 2003 Understanding Children‟s Work (UCW) Programme Villa Aldobrandini V. Panisperna 28 00184 Rome Tel: +39 06.4341.2008 Fax: +39 06.6792.197 Email: [email protected] As part of broader efforts toward durable solutions to child labor, the International Labour Organization (ILO), the United Nations Children‟s Fund (UNICEF), and the World Bank initiated the interagency Understanding Children‟s Work (UCW) project in December 2000. The project is guided by the Oslo Agenda for Action, which laid out the priorities for the international community in the fight against child labor. Through a variety of data collection, research, and assessment activities, the UCW project is broadly directed toward improving understanding of child labor, its causes and effects, how it can be measured, and effective policies for addressing it. For further information, see the project website at www.ucw-project.org. This paper is part of the research carried out within UCW (Understanding Children's Work), a joint ILO, World Bank and UNICEF project. The views expressed here are those of the authors' and should not be attributed to the ILO, the World Bank, UNICEF or any of these agencies‟ member countries. Understanding children’s work in Nepal Country Report July 2003 ABSTRACT The current report as part of UCW project activities in Nepal. It provides an overview of the child labour phenomenon in the Kingdom - its extent and nature, its determinants, its consequences on health and education, and national responses to it. -

Curbing Precarious Informal Employment and Bonded Labour in the Agriculture Sector of Nepal: GEFONT's Initiative to Liberate Kamaiyas

A Service of Leibniz-Informationszentrum econstor Wirtschaft Leibniz Information Centre Make Your Publications Visible. zbw for Economics Rimal, Bishnu Working Paper Curbing precarious informal employment and bonded labour in the agriculture sector of Nepal: GEFONT's initiative to liberate Kamaiyas Global Labour University Working Paper, No. 57 Provided in Cooperation with: The Global Labour University (GLU) Suggested Citation: Rimal, Bishnu (2019) : Curbing precarious informal employment and bonded labour in the agriculture sector of Nepal: GEFONT's initiative to liberate Kamaiyas, Global Labour University Working Paper, No. 57, International Labour Organization (ILO), Geneva This Version is available at: http://hdl.handle.net/10419/206727 Standard-Nutzungsbedingungen: Terms of use: Die Dokumente auf EconStor dürfen zu eigenen wissenschaftlichen Documents in EconStor may be saved and copied for your Zwecken und zum Privatgebrauch gespeichert und kopiert werden. personal and scholarly purposes. Sie dürfen die Dokumente nicht für öffentliche oder kommerzielle You are not to copy documents for public or commercial Zwecke vervielfältigen, öffentlich ausstellen, öffentlich zugänglich purposes, to exhibit the documents publicly, to make them machen, vertreiben oder anderweitig nutzen. publicly available on the internet, or to distribute or otherwise use the documents in public. Sofern die Verfasser die Dokumente unter Open-Content-Lizenzen (insbesondere CC-Lizenzen) zur Verfügung gestellt haben sollten, If the documents have been made available -

Report on Employment Relationship Survey in the Brick Industry in Nepal

Report On Employment Relationship Survey in The Brick Industry in Nepal Government of Nepal National Planning Commission Central Bureau of Statistics Report On Employment Relationship Survey in The Brick Industry in Nepal December 2020 Government of Nepal National Planning Commission Central Bureau of Statistics Copyright © International Labour Organization, United Nations Children’s Fund and Central Bureau of Statistics of Nepal (CBS), 2020 First published 2020 This is an open access work distributed under the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License (https:// creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0). Users can reuse, share, adapt and build upon the original work, as detailed in the License. The ILO, UNICEF and CBS must be clearly credited as the owners of the original work. The use of the emblems of the ILO, UNICEF and CBS is not permitted in connection with users’ work. Attribution – The work must be cited as follows: ILO, UNICEF and CBS, Report On Employment Relationship Survey in The Brick Industry in Nepal, Kathmandu: ILO, UNICEF, CBS, 2020. Translations – In case of a translation of this work, the following disclaimer must be added along with the attribution: This translation was not created by the International Labour Office (ILO), the United Nations Children’s Fund (UNICEF) or Central Bureau of Statistics of Nepal (CBS) and should not be considered an official ILO, UNICEF or CBS translation. The ILO, UNICEF and CBS are not responsible for the content or accuracy of this translation. Adaptations – In case of an adaptation of this work, the following disclaimer must be added along with the attribution: This is an adaptation of an original work by the International Labour Office (ILO), the United Nations Children’s Fund (UNICEF) and Central Bureau of Statistics of Nepal (CBS). -

Analysis of Watersheds in Gandaki Province, Nepal Using QGIS

TECHNICAL JOURNAL Vol 1, No.1, July 2019 Nepal Engineers' Association, Gandaki Province ISSN : 2676-1416 (Print) Pp.: 16-28 Analysis of Watersheds in Gandaki Province, Nepal Using QGIS Keshav Basnet*, Er. Ram Chandra Paudel and Bikash Sherchan Infrastructure Engineering and Management Program Department of Civil and Geomatics Engineering Pashchimanchal Campus, Institute of Engineering Tribhuvan University, Nepal *Email: [email protected] Abstract Gandaki province has the good potentiality of hydro-electricity generation with existing twenty- nine hydro-electricity projects. Since the Province is rich in water resources, analysis of watersheds needs to be done for management, planning and identification of water as well as natural resources. GIS offers integration of spatial and no spatial data to understand and analyze the watershed processes and helps in drawing a plan for integrated watershed development and management. The Digital Elevation Model (DEM) available on the NASA-Earth data has been taken as a primary data for morphometric analysis of watershed in Gandaki Province using QGIS. Delineation of watershed was conducted from a DEM by computing the flow direction and using it in the Watershed tool. Necessary fill sink correction was made before proceeding to delineation. A raster representing the direction of flow was created using Flow Direction tool to determine contributing area. Flow accumulation raster was created from flow direction raster using Flow Accumulation Tool. A point- based method has been used to delineate watershed for each selected point. The selected point may be an outlet, a gauge station or a dam. The annual rainfall data from ground meteorological stations has been used in QGIS to generate rainfall map for the study of rainfall pattern in the province and watersheds using IDW Interpolation method. -

Hydraulic Parameters for Sediment Transport and Prediction of Suspended Sediment for Kali Gandaki River Basin, Himalaya, Nepal

water Article Hydraulic Parameters for Sediment Transport and Prediction of Suspended Sediment for Kali Gandaki River Basin, Himalaya, Nepal Mahendra B. Baniya 1,2,*, Takashi Asaeda 3,4, Shivaram K.C. 5 and Senavirathna M.D.H. Jayashanka 1 1 Graduate School of Science and Engineering, Saitama University, 255 Shimo-okubo, Sakura-ku, Saitama 338-8570, Japan; [email protected] 2 Provincial Government, Ministry of Physical Infrastructure Development, Gandaki Province, Pokhara 33700, Nepal 3 Institute for studies of the Global Environment, 7-1 Sophia University, Kioicho, Chiyoda, Tokyo 102-0094, Japan; [email protected] 4 Hydro Technology Institute, 4-3-1 Shiroyama Trust Tower, Tranomon, Minato, Tokyo 105-0001, Japan 5 Nepal Electricity Authority, Central Office, Durbarmarga, Kathmandu 44600, Nepal; [email protected] * Correspondence: [email protected]; Tel.: +81-048-858-9186 Received: 22 May 2019; Accepted: 10 June 2019; Published: 12 June 2019 Abstract: Sediment yield is a complex phenomenon of weathering, land sliding, and glacial and fluvial erosion. It is highly dependent on the catchment area, topography, slope of the catchment terrain, rainfall, temperature, and soil characteristics. This study was designed to evaluate the key hydraulic parameters of sediment transport for Kali Gandaki River at Setibeni, Syangja, located about 5 km upstream from a hydropower dam. Key parameters, including the bed shear stress (τb), specific stream power (!), and flow velocity (v) associated with the maximum boulder size transport, were determined throughout the years, 2003 to 2011, by using a derived lower boundary equation. Clockwise hysteresis loops of the average hysteresis index of +1.59 were developed and an average of 40.904 12.453 Megatons (Mt) suspended sediment have been transported annually from the higher ± Himalayas to the hydropower reservoir.