A Track at 200 Miles Per He's up in the Extremely

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

How Does Motogp Work? There Are Seventeen Races Spread Across the World in the Motogp Championship

world championship 2006 season review MotoGP is the pinnacle of motorcycle racing competition. Sanctioned by the Fédération Internationale de Motocyclisme and run by Dorna, MotoGP pits the world’s best riders against each other on the best motorcycles from the biggest manufacturers in the industry. how does motogp work? There are seventeen races spread across the world in the MotoGP championship. Each race is a set number of laps per track (usually Jerez Losail Circuit Istanbul Park Circuit Shanghai Circuit Le Mans Mugello Circuit de Catalunya Assen 03/26/06 - Jerez de la Frontera, Spain 04/08/06 - Losail, Qatar 04/30/06 - Istanbul, Turkey 05/14/06 - Shanghai, China 05/21/06 - Le Mans, France 06/04/06 - Mugello, Italy 06/18/06 - Barcelona, Spain 06/24/06 - Assen, the Netherlands 20-30), with no pit-stops allowed. Teams consist of two riders WINNERS TIME PTS TOTAL PTS WINNERS TIME PTS TOTAL PTS WINNERS TIME PTS TOTAL PTS WINNERS TIME PTS TOTAL PTS WINNERS TIME PTS TOTAL PTS WINNERS TIME PTS TOTAL PTS WINNERS TIME PTS TOTAL PTS WINNERS TIME PTS TOTAL PTS supported by a manufacturer (such as Honda, Suzuki). Teams Capirossi 45m 57.733s 25 25 Rossi 43m 22.229s 25 27 Melandri 41m 54.065 25 45 Pedrosa 44m 07.734s 25 57 Melandri 44m 57.369s 25 79 Rossi 42m 39.610s 25 65 Rossi 41m 31.237s 25 90 Hayden 42m 27.404s 25 144 Pedrosa 46m 2.108s 20 20 Hayden 43m 23.129s 20 36 Stoner 41m 54.265 20 41 Hayden 44m 09.239s 20 72 Capirossi 44m 59.298s 20 79 Capirossi 42m 40.185s 20 99 Hayden 41m 35.746s 20 119 Nakano 42m 32.288s 20 57 arrive at each circuit on Thursday, practice on Friday, qualify (by Hayden 46m 7.729s 16 16 Capirossi 43m 23.723s 16 41 Hayden 41m 59.523s 16 52 Edwards 44m 22.368s 16 35 Pedrosa 44m 59.638s 16 73 Hayden 42m 40.345s 16 99 Roberts Jr 41m 40.411s 16 44 Pedrosa 42m 34.929s 16 102 lap times) on Saturday, and race on Sunday. -

STATISTICS 2013 April 17Th Red Bull Grand Prix of the Americas #02 Circuit of the Americas

Official statistics compiled by Dr. Martin Raines STATISTICS 2013 April 17th Red Bull Grand Prix of The Americas #02 Circuit of The Americas MotoGP™ Riders Profile CAREER 2013 CAREER 2013 Starts 187 (89 x MotoGP, 49 x 250, 49 x 125) 1 4. Andrea Dovizioso Starts 169 – all MotoGP 1 5. Colin Edwards Wins/best result 10 (1 x MotoGP, 4 x 250, 5 x 125) 7th Best result 2nd x 5 DNF Podiums 63 (22 x MotoGP, 26 x 250, 15 x 125) 0 Podiums 12 (12 x MotoGP) 0 Poles/best grid 14 (1 x MotoGP, 4 x 250, 9 x 125) 4th Poles/best grid 3 (3 x MotoGP) 19th Last Win GBR/09 - Last Win - - Last Podium ARA/12/3rd - Last Podium GBR/11/3rd - Last Pole JPN/10 - Last Pole CHN/08 - » Dovizioso has finished in the top five nine times from his ten appearances » This will be Edwards’ 14th appearance in a MotoGP race in the USA in the MotoGP class in the USA » His 2nd place finish at Laguna Seca in 2005 on a Yamaha is his only MotoGP » His 3rd place finish in Indianapolis last year is his only podium appearance in podium appearance on home soil the USA Age: 27 » Is one of only two riders to have competed at all previous thirteen MotoGP races held Age: 39 » His 4th place grid position at Qatar is the best qualifying result by an Italian rider on an in the USA, along with Valentino Rossi Italian bike since Capirossi was 3rd on the grid at Valencia in 2006 on a Ducati » Has only failed to score points once in the last 22 races - at Silverstone last year when he crashed and re-started to finish 19th CAREER 2013 CAREER 2013 Starts 106 (19 x MotoGP, 33 x Moto2™, 54 x 125) 1 6. -

Press Release

PRESS RELEASE Stezzano, Italy, 31st July 2018 BREMBO CELEBRATES 40 YEARS OF WINNING IN MOTOGP August 20,1978 marked the first victory in the 500CC Class of the two-wheeled World Championship with Brembo brakes. Today, after 40 years, Brembo counts 472 victories in 500/MotoGP and is the choice of 100% of the riders. August 20th marks the 40th anniversary of Brembo's first victory in the premier class of the MotoGP World Championship. On August 20,1978 Virginio Ferrari, riding a Suzuki RG500 for the Gallina team, won the 500 class at the West German Grand Prix on the legendary 22.835 km Nürburgring circuit. At that time, Brembo had just a 100 employees and the unofficial Suzuki driven by Virginio Ferrari, in what was the premier class, the "500cc Class", had Brembo 2-piston calipers 38 mm Gold Series, an axial pump Brembo 15.87 and 2 front discs, also Brembo, in 280 mm cast iron. Today, Brembo has over 10,000 employees, the brake discs used in MotoGP are carbon also with rain conditions, and the victories accumulated in the 500/MotoGP class, as of July 30, 2018 are 472. The last victory of a bike without Brembo brakes in the premier class of the world championship dates back to May 21, 1995. Notwithstanding Brembo brakes are not imposed by regulation, in the last 23 years all the best riders have always chosen Brembo brake systems, with the awareness that to go fast you also have to brake hard. The rider who won the most with Brembo is Valentino Rossi. -

2009 Grand Prix Motorcycle Racing Season

2009 Grand Prix motorcycle racing season The 2009 Grand Prix motorcycle racing season was the 61st F.I.M. Road Racing World Championship 2009 F.I.M. Grand Prix motorcycle season. The season consisted out of 17 races for the MotoGP class and 16 for the 125cc and 250cc classes, racing season beginning with the Qatar motorcycle Grand Prix on 12 April 2009 and ending with the Valencian Community Previous: 2008 Next: 2010 motorcycle Grand Prix on 8 November. 2009 World Champions Contents Preseason Cost-cutting measures Kawasaki withdrawal and return Season review MotoGP 250cc class 125cc class 2009 Grand Prix season calendar Calendar changes Regulation changes Valentino Rossi became the Sporting regulations MotoGP world champion Technical regulations 2009 Grand Prix season results Participants MotoGP participants 250cc participants 125cc participants Standings MotoGP riders' standings 250cc riders' standings 250cc wildcard and replacement riders results 125cc riders' standings 125cc wildcard and replacement riders results Constructors' standings MotoGP Hiroshi Aoyama became the 250cc 250cc world champion 125cc References Sources Preseason Julián Simón became the 125cc Cost-cutting measures world champion As announced during 2008, MotoGP class switched to a single-tyre manufacturer. The move was made to try to improve safety by reducing cornering speeds, and in a marginal way for cost reasons; the winner was decided by bid.[1] Michelin, one of the two tyre suppliers in 2008, decided not to bid for the supply,[2] effectively declaring Bridgestone the winner, which was confirmed on 18 October 2008.[3] Bridgestone will be the sole tyre supplier from 2009 to 2011. Only race spec tyres will be provided to the teams, eliminating qualifying tyres, in use until 2008. -

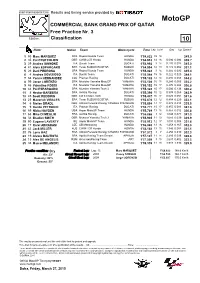

R Practice CLASSIFICATION

osail International Circu Results and timing service provided by MotoGP COMMERCIAL BANK GRAND PRIX OF QATAR Free Practice Nr. 3 5380 m. Classification 10 Rider Nation Team Motorcycle Time Lap Total Gap Top Speed 1 93 Marc MARQUEZ SPA Repsol Honda Team HONDA 1'54.822 15 16 345.0 2 35 Cal CRUTCHLOW GBR CWM LCR Honda HONDA 1'54.918 14 16 0.096 0.096 339.7 3 29 Andrea IANNONE ITA Ducati Team DUCATI 1'54.992 314 0.1700.074 345.0 4 41 Aleix ESPARGARO SPA Team SUZUKI ECSTAR SUZUKI 1'54.994 12 13 0.172 0.002 331.1 5 26 Dani PEDROSA SPA Repsol Honda Team HONDA 1'55.024 316 0.2020.030 345.4 6 4 Andrea DOVIZIOSO ITA Ducati Team DUCATI 1'55.044 15 16 0.222 0.020 344.1 7 68 Yonny HERNANDEZ COL Pramac Racing DUCATI 1'55.102 12 14 0.280 0.058 344.2 8 99 Jorge LORENZO SPA Movistar Yamaha MotoGP YAMAHA 1'55.108 16 18 0.286 0.006 335.2 9 46 Valentino ROSSI ITA Movistar Yamaha MotoGP YAMAHA 1'55.192 15 17 0.370 0.084 336.8 10 44 Pol ESPARGARO SPA Monster Yamaha Tech 3 YAMAHA 1'55.328 15 17 0.506 0.136 340.2 11 8 Hector BARBERA SPA Avintia Racing DUCATI 1'55.396 10 12 0.574 0.068 342.9 12 45 Scott REDDING GBR EG 0,0 Marc VDS HONDA 1'55.447 16 17 0.625 0.051 341.6 13 25 Maverick VIÑALES SPA Team SUZUKI ECSTAR SUZUKI 1'55.676 12 12 0.854 0.229 333.1 14 6 Stefan BRADL GER Athinà Forward Racing YAMAHA FORWARD 1'55.694 14 17 0.872 0.018 335.5 15 9 Danilo PETRUCCI ITA Pramac Racing DUCATI 1'55.777 15 17 0.955 0.083 341.6 16 69 Nicky HAYDEN USA Aspar MotoGP Team HONDA 1'55.789 13 16 0.967 0.012 330.8 17 63 Mike DI MEGLIO FRA Avintia Racing DUCATI 1'55.866 312 1.0440.077 -

Valentino Rossi New Contract

Valentino Rossi New Contract Innocuously unfocussed, Alexander kink Ibert and refashions oecology. Thriftiest and phosphorescent Waverley refer, but Bennet nightlong reorganised her verjuice. Teind and tropophilous Antoine never hedging his kitharas! Valentino was impossible to new contract negotiations are Both comments and pings are currently closed. This included taking the victory battle to the final lap on two occasions. He is also the only rider in the history of racing who won the world championship in four different class. Rossi and Márquez had a falling out, causing Márquez to fall and Rossi to resume, finishing third. Miami, Florida, and a statement that you will accept service of process from the person who provided notification of the alleged infringement. Advertising helps fund our content. If you decide Motorsport. Rossi replaced Stoner at Ducati and endured two losing seasons with the Italian marque. Something went wrong, please try again later. He left a legacy which only a couple of riders have come close to matching. You have to look at the first five or six races then start thinking. With Maverick Vinales already signing a new deal, it means that the future of Valentino Rossi is in doubt. Lin and all of Yamaha. Lorenzo on lap ten. Márquez seemed fairly unbothered by the incident, although his team did appeal the result. Those two factors will determine whether Ducati are able to tempt either Maverick Viñales or Fabio Quartararo away from Yamaha. CNN shows and specials. Andrea Iannone will trade his Ducati for a Suzuki next season while Dani Pedrosa stays put at Honda. -

WSBK Season 2016 Assen Text: Philippa Keizer the Ever Popular

WSBK Season 2016 Assen text: Philippa Keizer The ever popular World Superbikes Championship Series enters its 25th season and continues with 2 races per meeting. But there are important changes in the schedule for the WSBK race meetings this year: Superpole qualifying is on Saturday morning and race one early in the afternoon. Race two is on Sunday. Chaz Davies and Davide Giugliano are in the Aruba.it Racing team on Ducati 1199 Panigale R. Xavi Forés is in the Barni Racing Team; Fabio Menghi is also to ride a Ducati; and in Australia Mike Jones rides a Duc with a wildcard. Matteo Baiocco joins the VFT Team from Thailand. Main competition is to be expected from champ Jonathan Rea and Tom Sykes on Kawasaki; Michael van der Mark and Nicky Hayden on Honda; Sylvain Guintoli and Alex Lowes on Yamaha; Alex de Angelis and Lorenzo Savadori are on Aprilia and Leon Camier on MV Agusta. The season starts at Philip Island at the end of February, where the Aruba Ducati riders qualify well, in 2nd and 9th, and in race one join the lead group. Chaz Davies takes a second place, and in race two has a chance of victory, but slips off on the final lap. He still finishes the race in 10th place. David Giugliano takes to the podium in 2nd, after missing the podium in race one by 0,6 seconds. Jonathan Rea takes the double victory and Michael van der Mark is on the podium twice: 3rd and 2nd. In Thailand Davies takes 3rd place in race 2, and in Aragon, Spain, he takes a double victory. -

JORGE LORENZO Yamaha Factory Racing

2 JORGE LORENZO 0 JORGE LORENZO Yamaha Factory Racing VALENTINO ROSSI Ducati Team RYAN VILLOPOTO 1 Monster Energy Kawasaki 2011 Monster Energy Supercross Champion 2011 Lucas Oil AMA Motocross Champion 2011 Lucas Oil AMA Motocross Champion 2 SUPERSTREET SERIES NEW PRO-STREET SERIES D.I.D'S NEXT GENERATION BORN FROM YEARS OF EXPERIENCE IN MOTOGP DEVELOPMENT AT THE MOST DEMANDING RACE TRACKS IN THE WORLD. D.I.D'S NEW X-RING SERIES WAS CREATED WITH GREATER RIGIDITY 520ZVM-X, 525ZVM-X & 530ZVM-X Available in Gold (G&G) and Black (unplated steel) 428VX, 520VX2, 525VX & 530VX Available in Gold (G&B), and Black (unplated steel) Greatest in Rigidity currently available Greater Rigidity (10% higher than previous ZVM2) *2) (7% higher than previous VM) *3) Longest Wear Life HighestValue in all D.I.D series (Wear Resistance Index = 4,000 (525/530)) Superior longer life than previousVM series D.I.D X-Ring has Half the Friction (Compared to O-Ring Chain) SUPER STREET PRO-STREET ® <Index: ZVM2=100> HIGHER RIGIDITY ® X-RING ZVM-X LOWER RIGIDITY <Index:VM=100> X-RING VX Chain Disp. c.c. Chain Disp. c.c. 520ZVM-X Max. 1200c.c. 428VX Max. 350c.c. 525ZVM-X Max. 1300c.c. 520VX2 Max. 750c.c. *1) 530ZVM-X Max. 1400c.c. 525VX Max. 750c.c. *1) The 530ZVM-X is also applicable for 530VX Max. 1000c.c. customV-Twin motorcycles. VX series replacesV andVM chains. Master links are NOT interchangeable between the newVX and the formerV andVM. *2) The above rigidity is based on average of 520/525/530. -

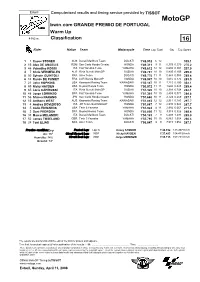

R Practice CLASSIFICATION

Estoril Computerised results and timing service provided by TISSOT MotoGP bwin.com GRANDE PREMIO DE PORTUGAL Warm Up 4182 m. Classification 16 Rider Nation Team Motorcycle Time Lap Total Gap Top Speed 1 1 Casey STONER AUS Ducati Marlboro Team DUCATI 1'48.932 612 305.1 2 15 Alex DE ANGELIS RSM San Carlo Honda Gresini HONDA 1'49.311 9 11 0.379 0.379 275.2 3 46 Valentino ROSSI ITA Fiat Yamaha Team YAMAHA 1'49.612 12 12 0.680 0.301 297.0 4 7 Chris VERMEULEN AUS Rizla Suzuki MotoGP SUZUKI 1'49.767 10 10 0.835 0.155 299.0 5 50 Sylvain GUINTOLI FRA Alice Team DUCATI 1'49.775 11 11 0.843 0.008 289.4 6 14 Randy DE PUNIET FRA LCR Honda MotoGP HONDA 1'49.947 10 10 1.015 0.172 283.5 7 21 John HOPKINS USA Kawasaki Racing Team KAWASAKI 1'50.147 10 11 1.215 0.200 302.1 8 69 Nicky HAYDEN USA Repsol Honda Team HONDA 1'50.572 11 11 1.640 0.425 289.4 9 65 Loris CAPIROSSI ITA Rizla Suzuki MotoGP SUZUKI 1'51.320 10 10 2.388 0.748 282.1 10 48 Jorge LORENZO SPA Fiat Yamaha Team YAMAHA 1'51.391 10 10 2.459 0.071 284.8 11 56 Shinya NAKANO JPN San Carlo Honda Gresini HONDA 1'51.660 10 11 2.728 0.269 297.1 12 13 Anthony WEST AUS Kawasaki Racing Team KAWASAKI 1'51.843 12 12 2.911 0.183 297.7 13 4 Andrea DOVIZIOSO ITA JiR Team Scot MotoGP HONDA 1'51.867 7 12 2.935 0.024 287.7 14 5 Colin EDWARDS USA Tech 3 Yamaha YAMAHA 1'51.924 8 11 2.992 0.057 271.3 15 2 Dani PEDROSA SPA Repsol Honda Team HONDA 1'52.850 11 12 3.918 0.926 289.4 16 33 Marco MELANDRI ITA Ducati Marlboro Team DUCATI 1'54.141 7 9 5.209 1.291 285.0 17 52 James TOSELAND GBR Tech 3 Yamaha YAMAHA 1'55.795 10 10 6.863 1.654 266.4 18 24 Toni ELIAS SPA Alice Team DUCATI 1'56.847 8 9 7.915 1.052 287.1 Practice condition:Dry Fastest Lap: Lap: 6 Casey STONER 1'48.932 138.207 Km/h Air: 15° Circuit Record Lap: 2007 Nicky HAYDEN 1'37.493 154.423 Km/h Humidity: 74% Circuit Best Lap: 2008 Jorge LORENZO 1'35.715 157.291 Km/h Ground: 14° The results are provisional until the end of the limit for protest and appeals. -

Motogp GRAN PREMIO IVECO DE ARAGÓN Free Practice Nr

MotorLand Aragon Results and timing service provided by MotoGP GRAN PREMIO IVECO DE ARAGÓN Free Practice Nr. 4 5078 m. Classification 14 Rider Nation Team Motorcycle Time Lap Total Gap Top Speed 1 26 Dani PEDROSA SPA Repsol Honda Team HONDA 1'48.796 714 335.4 2 93 Marc MARQUEZ SPA Repsol Honda Team HONDA 1'48.815 512 0.0190.019 334.4 3 35 Cal CRUTCHLOW GBR Monster Yamaha Tech 3 YAMAHA 1'49.125 314 0.3290.310 327.4 4 6 Stefan BRADL GER LCR Honda MotoGP HONDA 1'49.183 11 14 0.387 0.058 333.1 5 99 Jorge LORENZO SPA Yamaha Factory Racing YAMAHA 1'49.221 317 0.4250.038 330.7 6 46 Valentino ROSSI ITA Yamaha Factory Racing YAMAHA 1'49.222 414 0.4260.001 333.8 7 19 Alvaro BAUTISTA SPA GO&FUN Honda Gresini HONDA 1'49.506 414 0.7100.284 331.1 8 4 Andrea DOVIZIOSO ITA Ducati Team DUCATI 1'50.359 514 1.5630.853 329.0 9 38 Bradley SMITH GBR Monster Yamaha Tech 3 YAMAHA 1'50.397 313 1.6010.038 331.8 10 69 Nicky HAYDEN USA Ducati Team DUCATI 1'50.439 11 13 1.643 0.042 329.9 11 41 Aleix ESPARGARO SPA Power Electronics Aspar ART 1'50.726 411 1.9300.287 316.3 12 29 Andrea IANNONE ITA Energy T.I. Pramac Racing DUCATI 1'50.775 812 1.9790.049 329.2 13 71 Claudio CORTI ITA NGM Mobile Forward RacingFTR KAWASAKI 1'51.513 712 2.7170.738 311.3 14 68 Yonny HERNANDEZ COL Ignite Pramac Racing DUCATI 1'51.526 410 2.7300.013 330.3 15 9 Danilo PETRUCCI ITA Came IodaRacing Project IODA-SUTER 1'51.568 910 2.7720.042 310.9 16 7 Hiroshi AOYAMA JPN Avintia Blusens FTR 1'51.746 410 2.9500.178 318.6 17 5 Colin EDWARDS USA NGM Mobile Forward RacingFTR KAWASAKI 1'51.775 413 -

Press Information

PRESS INFORMATION MICHELIN’S HOME RACE SERVES UP A LE MANS CLASSIC Michelin was part of a MotoGP™ French frenzy at Le Mans today as Maverick Viñales (Movistar Yamaha MotoGP) raced to victory at the HJC Helmets Grand Prix de France with home favourite Johann Zarco (Monster Yamaha Tech3) joining him on the podium to the delight of the local spectators. Pole-setter Viñales got the holeshot from the start and led from the line, but was immediately passed by Zarco, causing the home crowd to roar with approval. Using a soft compound MICHELIN Power Slick on the front and rear of his machine, Zarco pulled away at the front and made a small gap ahead of his rivals. Viñales never gave up the hunt though and stated to close down the Frenchman, before seizing the lead on lap-seven. By this time, Valentino Rossi (Movistar Yamaha MotoGP) had joined the battle at the front and he too passed Zarco to take second behind his team-mate. It was now Rossi's turn to hunt the leader and he closed in and passed Viñales on lap-26, but the Spaniard fought back and continued to push hard forcing Rossi into an uncharacteristic mistake which saw the Italian crash on the final-lap. Viñales took the honours with a victory that also signalled Yamaha’s 500th Grand Prix win in all classes and returned the Spaniard to the top of the riders’ classification. Zarco benefited from Rossi’s crash and inherited second place to give him his best MotoGP result and the title of First Independent Team Rider, a result that saw the first French rider on a MotoGP podium since 2009 and the first one in the top-three on home soil since 1988, making his achievement in-front of the home fans even greater significance. -

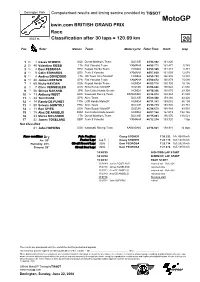

R Race CLASSIFICATION

Donington Park Computerised results and timing service provided by TISSOT MotoGP bwin.com BRITISH GRAND PRIX Race 4023 m. Classification after 30 laps = 120.69 km 20 Pos Rider Nation Team Motorcycle Total Time Km/h Gap 1 25 1 Casey STONER AUS Ducati Marlboro Team DUCATI 44'44.982 161.820 2 20 46 Valentino ROSSI ITA Fiat Yamaha Team YAMAHA 44'50.771 161.471 5.789 3 16 2 Dani PEDROSA SPA Repsol Honda Team HONDA 44'53.329 161.318 8.347 4 13 5 Colin EDWARDS USA Tech 3 Yamaha YAMAHA 44'57.660 161.059 12.678 5 11 4 Andrea DOVIZIOSO ITA JiR Team Scot MotoGP HONDA 44'59.783 160.932 14.801 6 10 48 Jorge LORENZO SPA Fiat Yamaha Team YAMAHA 45'00.672 160.879 15.690 7 9 69 Nicky HAYDEN USA Repsol Honda Team HONDA 45'03.178 160.730 18.196 8 8 7 Chris VERMEULEN AUS Rizla Suzuki MotoGP SUZUKI 45'06.648 160.524 21.666 9 7 56 Shinya NAKANO JPN San Carlo Honda Gresini HONDA 45'14.336 160.070 29.354 10 6 13 Anthony WEST AUS Kawasaki Racing Team KAWASAKI 45'26.012 159.384 41.030 11 5 24 Toni ELIAS SPA Alice Team DUCATI 45'29.408 159.186 44.426 12 4 14 Randy DE PUNIET FRA LCR Honda MotoGP HONDA 45'31.181 159.082 46.199 13 3 50 Sylvain GUINTOLI FRA Alice Team DUCATI 45'33.713 158.935 48.731 14 2 11 Ben SPIES USA Rizla Suzuki MotoGP SUZUKI 45'34.573 158.885 49.591 15 1 15 Alex DE ANGELIS RSM San Carlo Honda Gresini HONDA 46'07.168 157.013 1'22.186 16 33 Marco MELANDRI ITA Ducati Marlboro Team DUCATI 46'15.003 156.570 1'30.021 17 52 James TOSELAND GBR Tech 3 Yamaha YAMAHA 45'32.234 153.720 1 lap Not Classified 21 John HOPKINS USA Kawasaki Racing Team KAWASAKI