Choiseul, Solomon Islands

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

State of the Coral Triangle: Solomon Islands

State of the Coral Triangle: Solomon Islands One of a series of six reports on the status of marine resources in the western Pacific Ocean, the State of the Coral Triangle: Solomon Islands describes the biophysical characteristics of Solomon Islands’ coastal and marine ecosystems, the manner in which they are being exploited, the framework in place that governs their use, the socioeconomic characteristics of the communities that use them, and the environmental threats posed by the manner in which STATE OF THE CORAL TRIANGLE: they are being used. It explains the country’s national plan of action to address these threats and improve marine resource management. Solomon Islands About the Asian Development Bank ADB’s vision is an Asia and Pacific region free of poverty. Its mission is to help its developing member countries reduce poverty and improve the quality of life of their people. Despite the region’s many successes, it remains home to approximately two-thirds of the world’s poor: 1.6 billion people who live on less than $2 a day, with 733 million struggling on less than $1.25 a day. ADB is committed to reducing poverty through inclusive economic growth, environmentally sustainable growth, and regional integration. Based in Manila, ADB is owned by 67 members, including 48 from the region. Its main instruments for helping its developing member countries are policy dialogue, loans, equity investments, guarantees, grants, and technical assistance. Asian Development Bank 6 ADB Avenue, Mandaluyong City 1550 Metro Manila, Philippines www.adb.org Printed on recycled paper Printed in the Philippines STATE OF THE CORAL TRIANGLE: Solomon Islands © 2014 Asian Development Bank All rights reserved. -

Recent Dispersal Events Among Solomon Island Bird Species Reveal Differing Potential Routes of Island Colonization

Recent dispersal events among Solomon Island bird species reveal differing potential routes of island colonization By Jason M. Sardell Abstract Species assemblages on islands are products of colonization and extinction events, with traditional models of island biogeography emphasizing build-up of biodiversity on small islands via colonizations from continents or other large landmasses. However, recent phylogenetic studies suggest that islands can also act as sources of biodiversity, but few such “upstream” colonizations have been directly observed. In this paper, I report four putative examples of recent range expansions among the avifauna of Makira and its satellite islands in the Solomon Islands, a region that has recently been subject to extensive anthropogenic habitat disturbance. They include three separate examples of inter-island dispersal, involving Geoffroyus heteroclitus, Cinnyris jugularis, and Rhipidura rufifrons, which together represent three distinct possible patterns of colonization, and one example of probable downslope altitudinal range expansion in Petroica multicolor. Because each of these species is easily detected when present, and because associated localities were visited by several previous expeditions, these records likely represent recent dispersal events rather than previously-overlooked rare taxa. As such, these observations demonstrate that both large landmasses and small islands can act as sources of island biodiversity, while also providing insights into the potential for habitat alteration to facilitate colonizations and range expansions in island systems. Author E-mail: [email protected] Pacific Science, vol. 70, no. 2 December 16, 2015 (Early view) Introduction The hypothesis that species assemblages on islands are dynamic, with inter-island dispersal playing an important role in determining local community composition, is fundamental to the theory of island biogeography (MacArthur and Wilson 1967, Losos and Ricklefs 2009). -

The Naturalist and His 'Beautiful Islands'

The Naturalist and his ‘Beautiful Islands’ Charles Morris Woodford in the Western Pacific David Russell Lawrence The Naturalist and his ‘Beautiful Islands’ Charles Morris Woodford in the Western Pacific David Russell Lawrence Published by ANU Press The Australian National University Canberra ACT 0200, Australia Email: [email protected] This title is also available online at http://press.anu.edu.au National Library of Australia Cataloguing-in-Publication entry Author: Lawrence, David (David Russell), author. Title: The naturalist and his ‘beautiful islands’ : Charles Morris Woodford in the Western Pacific / David Russell Lawrence. ISBN: 9781925022032 (paperback) 9781925022025 (ebook) Subjects: Woodford, C. M., 1852-1927. Great Britain. Colonial Office--Officials and employees--Biography. Ethnology--Solomon Islands. Natural history--Solomon Islands. Colonial administrators--Solomon Islands--Biography. Solomon Islands--Description and travel. Dewey Number: 577.099593 All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying or otherwise, without the prior permission of the publisher. Cover image: Woodford and men at Aola on return from Natalava (PMBPhoto56-021; Woodford 1890: 144). Cover design and layout by ANU Press Printed by Griffin Press This edition © 2014 ANU Press Contents Acknowledgments . xi Note on the text . xiii Introduction . 1 1 . Charles Morris Woodford: Early life and education . 9 2. Pacific journeys . 25 3 . Commerce, trade and labour . 35 4 . A naturalist in the Solomon Islands . 63 5 . Liberalism, Imperialism and colonial expansion . 139 6 . The British Solomon Islands Protectorate: Colonialism without capital . 169 7 . Expansion of the Protectorate 1898–1900 . -

Pacific Islands Herpetology, No. V, Guadalcanal, Solomon Islands. A

Great Basin Naturalist Volume 11 Article 1 Number 3 – Number 4 12-29-1951 Pacific slI ands herpetology, No. V, Guadalcanal, Solomon Islands. A check list of species Vasco M. Tanner Brigham Young University Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarsarchive.byu.edu/gbn Recommended Citation Tanner, Vasco M. (1951) "Pacific slI ands herpetology, No. V, Guadalcanal, Solomon Islands. A check list of species," Great Basin Naturalist: Vol. 11 : No. 3 , Article 1. Available at: https://scholarsarchive.byu.edu/gbn/vol11/iss3/1 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Western North American Naturalist Publications at BYU ScholarsArchive. It has been accepted for inclusion in Great Basin Naturalist by an authorized editor of BYU ScholarsArchive. For more information, please contact [email protected], [email protected]. U8fW Ul 22 195; The Gregft fiasib IfJaturalist Published by the Department of Zoology and Entomology Brigham Young University, Provo, Utah Volume XI DECEMBER 29, 1951 Nos. III-IV PACIFIC ISLANDS HERPETOLOGY, NO. V GUADALCANAL, SOLOMON ISLANDS: l A CHECK LIST OF SPECIES ( ) VASCO M. TANNER Professor of Zoology and Entomology Brigham Young University Provo, Utah INTRODUCTION This paper, the fifth in the series, deals with the amphibians and reptiles, collected by United States Military personnel while they were stationed on several of the Solomon Islands. These islands, which were under the British Protectorate at the out-break of the Japanese War in 1941, extend for about 800 miles in a southeast direction from the Bismarck Archipelago. They lie south of the equator, between 5° 24' and 10° 10' south longitude and 154° 38' and 161° 20' east longitude, which is well within the tropical zone. -

Another New Member of the Varanus (Euprepiosaurus) Indicus Group (Sauria, Varanidae): an Undescribed Species from Rennen Island, Solomon Islands

Another new member of the Varanus (Euprepiosaurus) indicus group (Sauria, Varanidae): an undescribed species from Rennen Island, Solomon Islands WOLFGANG BöHME, KAI PHILIPP & THOMAS ZIEGLER Abstract A new species ofbig-growing monitor lizard is described from Rennell Island, Solomon Islands. lt is a member of the Varanus indicus group within the subgenus Euprepiosaurus FITZINGER and is distinguished from all other representatives ofthis group by the combination of several scalation characters, colour pattern, and hemipenial characters. Above all, the new species is characterized by a weakly compressed tail being roundish in its proximal third where it lacks a double-crested mediankeel. Key words: Sauria: Varanidae: Varanus (Euprepiosaurus) indicus group; new species; Solomon Islands: Rennell Island. Zusammenfassung Ein weiteres neues Mitglied der Varanus (Euprepiosaurus) indicus-Gruppe ( Sauria: Varanidae ): Eine unbeschriebene Art von der Insel Rennell, Salomonen . ' Wir beschreiben eine neue, großwüchsige Waranart von der zu den Salomonen gehörenden, weit abseits im südöstlichen Pazifik liegenden Rennell-Insel, deren Belegexemplare aus dem Zoologi schen Museum der Universität Kopenhagen bereits 1962 während der Noona-Dan-Schiffs expedition gesammelt worden waren. Die neue Art gehört - innerhalb der Untergattung Eupre piosaurus FnZTNGER - zur Varanus indicus-Gruppe und unterscheidet sich von allen neun bisher bekannten Arten dieser Gruppe (V. caerulivirens, V. cerambonensis, V. doreanus, V. finschi, V. indicus, V. jobiensis, V. melinus, V. spinulosus und V. yuwonoi) durch die Kombination folgender Merkmale: Fehlende Blaufärbung; Schwanz ungebändert; kein Schläfen band; helle, ungezeichnete Kehlregion; retikulierte bis ozellierte Bauchzeichnung beim Jungtier; helle, nur im Vorderbereich undeutlich pigmentierte Zunge; Hemipenis mit nur an einer Seite ausgebildeten, sich zum äußeren der beiden apikalen Loben erstreckenden Paryphasmata. -

R"Eih||J| Fieldiana May121977

nC* C R"EIH||J| FIELDIANA MAY121977 HH* llwail UiM1'v Anthropology Published by Field Museum of Natural History Volume 68. No. 1 April 28, 1977 Human Biogeography in the Solomon Islands John Terrell Associate Curator, Oceanic ArchaeoijOGY and Ethnology Field Museum of Natural History As Ernst Mayr (1969) has observed, the "richness of tropical faunas and floras is proverbial." Although the degree of species diversity in the tropics has at times been exaggerated, tropical bird faunas, for example, "contain at least three times if not four or more times as many species, as comparable temperate zone bird faunas." It is not surprising then that a tropical island as large as New Guinea in the southwestern Pacific has played a special role in the refinement of evolutionary theory ( Diamond, 1971, 1973). In similar fashion, anthropologists have long recognized that the Melanesian islands of the Pacific, including New Guinea, are re- markable for the extreme degree of ethnic diversity encountered on them (fig. 1). While the magnitude of the dissimilarities among these tropical human populations has been occasionally overstated or misconstrued (Vayda, 1966), even casual survey of the findings made by social anthropologists, archaeologists, physical anthro- pologists, and linguists in Melanesia would confirm Oliver's (1962, p. 63) assessment that no other region of the world "contains such cultural variety as these islands." It is not an accident that zoologists, botanists, and anthropolo- gists have observed that one word, diversity, so aptly sums up the character of tropical populations in general, and the island popula- tions of Melanesia in particular. This common judgment, however, has not led to the development of a shared set of concepts and models, applicable at least in part both to lower organisms and to man, to account for that diversity. -

Species-Edition-Melanesian-Geo.Pdf

Nature Melanesian www.melanesiangeo.com Geo Tranquility 6 14 18 24 34 66 72 74 82 6 Herping the final frontier 42 Seahabitats and dugongs in the Lau Lagoon 10 Community-based response to protecting biodiversity in East 46 Herping the sunset islands Kwaio, Solomon Islands 50 Freshwater secrets Ocean 14 Leatherback turtle community monitoring 54 Freshwater hidden treasures 18 Monkey-faced bats and flying foxes 58 Choiseul Island: A biogeographic in the Western Solomon Islands stepping-stone for reptiles and amphibians of the Solomon Islands 22 The diversity and resilience of flying foxes to logging 64 Conservation Development 24 Feasibility studies for conserving 66 Chasing clouds Santa Cruz Ground-dove 72 Tetepare’s turtle rodeo and their 26 Network Building: Building a conservation effort network to meet local and national development aspirations in 74 Secrets of Tetepare Culture Western Province 76 Understanding plant & kastom 28 Local rangers undergo legal knowledge on Tetepare training 78 Grassroots approach to Marine 30 Propagation techniques for Tubi Management 34 Phantoms of the forest 82 Conservation in Solomon Islands: acts without actions 38 Choiseul Island: Protecting Mt Cover page The newly discovered Vangunu Maetambe to Kolombangara River Island endemic rat, Uromys vika. Image watershed credit: Velizar Simeonovski, Field Museum. wildernesssolomons.com WWW.MELANESIANGEO.COM | 3 Melanesian EDITORS NOTE Geo PRODUCTION TEAM Government Of Founder/Editor: Patrick Pikacha of the priority species listed in the Critical Ecosystem [email protected] Solomon Islands Hails Partnership Fund’s investment strategy for the East Assistant editor: Tamara Osborne Melanesian Islands. [email protected] Barana Community The Critical Ecosystem Partnership Fund (CEPF) Contributing editor: David Boseto [email protected] is designed to safeguard Earth’s most biologically rich Prepress layout: Patrick Pikacha Nature Park Initiative and threatened regions, known as biodiversity hotspots. -

ISSUE 71 Be the Captain of Your Own Ship

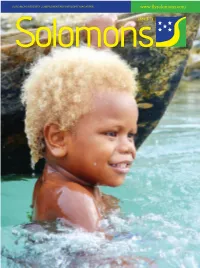

SOLOMON AIRLINE’S COMPLIMENTARY INFLIGHT MAGAZINE www.flysolomons.com SolomonsISSUE 71 be the captain of your own ship You are in good hands with AVIS To make a reservation, please contact: Ela Motors Honiara, Prince Philip Highway Ranadi, Honiara Phone: (677) 24180 or (677) 30314 Fax: (677) 30750 Email:[email protected] Web: www.avis.com Monday to Friday 8:00am to 5:00pm - Saturday – 8:00am to 12:00pm - Sunday – 8.00am to 12:00pm Solomons www.flysolomons.com WELKAM FRENS T o a l l o u r v a l u e d c u s t o m e r s Mifala hapi tumas fo wishim evriwan, Meri Xmas and Prosperous and Safe New Year Ron Sumsum Chief Executive Officer Partnerships WELKAM ABOARD - QANTAS; -our new codeshare partnership commenced Best reading ahead on the 15th November 2015. Includes the following- This is a major milestone for both carriers considering our history together now re-engaged. • Cultural Identity > the need to foster our cultures Together, Qantas and Solomon Airlines will service Australia with four (4) weekly services to and from Brisbane and one (1) service to Sydney • Love is in the Air > a great wedding story on the beautiful Papatura with the best connections within Australia and Trans-Tasman and Resort in Santa Isabel Domestically within Australia as well as Worldwide. This is a mega partnership from our small and friendly Hapi Isles. • The Lagoon Festival > the one Festival that should not be missed Furthermore, we expect to commence a renewed partnership with our annually Melanesian brothers in Air Vanuatu with whom we plan to commence our codeshare from Honiara to Port Vila and return each Saturday and • The Three Sisters Islands of Makira > with the Crocodile Whisperers Sunday each week. -

Solomon Islands

Conserved coconut germplasm from Solomon Islands Genebank Contact Dodo Creek Research Station Country member of COGENT PO Box G13 Dr Jimie Saelea Honiara Director, Research Solomon Islands Ministry of Agriculture and Primary Industries PO Box G13, Honiara Solomon Islands Phone: (677) 20308 / 31111 / 21327 Fax: (677) 21955 / 31037 Email: [email protected] The Solomon Islands is a country in Melanesia, east of Papua New Guinea, consisting of nearly 1000 islands. Together they cover a land mass of 28,400 km². As of 2006, the vast majority of the 552,438 people living on the Solomon Islands are ethnically Melanesian (94.5%) followed by Polynesian (3%) and Micronesian (1.2%). A history of the coconut industry in Solomon Islands is given by Ilala (1989). Since the ethnic tension in 1998, copra and cocoa have been the focus of most international extension and development projects. Moves to introduce high-yielding hybrids were unsuccessful in most cases because of resistance by farmers, poor husbandry and susceptibility to pest, disease and weed infestation. Coconut research has been carried out since 1952 in the Solomon Islands. In 1960 a Joint Coconut Research Scheme was established by the Solomon Island Government and the Levers company, Russell Islands Plantation Estates Ltd, based at Yandina, Central Province. A seed garden for the production of Dwarf x Tall hybrids seednuts was producing up to 240,000 seednuts a year. Sixteen coconut varieties were also conserved at Yandina, until the blaze at the Dodo Creek Research Station in 2000. Levers was the largest single producer and buyer of copra and cocoa in the country (and the largest employer), but the company was declared bankrupt in 2001. -

Pairwise Co-Existence of Bismarck and Solomon Landbird Species

Evolutionary Ecology Research, 2009, 11: 1–16 Pairwise co-existence of Bismarck and Solomon landbird species James G. Sanderson1, Jared M. Diamond2 and Stuart L. Pimm3 1Wildlife Conservation Network, Los Altos, California, 2Geography Department, University of California, Los Angeles, California and 3Nicholas School of the Environment, Duke University, Durham, North Carolina, USA ABSTRACT Questions: Can the difference between chance and pattern be determined by the composition of species across islands in an archipelago? In particular, will one find ‘checkerboards’ – a pattern of mutual exclusivity that is the simplest pattern that might occur under competitive exclusion? Organisms: 150 and 141 species of land birds inhabiting 41 and 142 islands of the Bismarck and the Solomon Archipelagos, respectively. (See http://evolutionary-ecology.com/data/ 2447_Supplement.pdf) Analytical methods: For each pair of species within each archipelago, the observed number of co-occurrences is compared to the distribution of the number of co-occurrences derived from a collection of 106 representative unique random, or null, communities. Those species pairs actually co-occurring less often than they do in 5% of those nulls are ‘unusually negative’ pairs; those co-occurring more often than they do in 95% of those nulls are ‘unusually positive’ pairs. Islands are ranked from those with the smallest number of species to the largest. A species incidence is the span from the smallest to the largest number of species on islands on which it is found. Results: In each archipelago, proportionately more congeneric species pairs than non- congeneric species pairs are unusually negative pairs. This holds even for species pairs that overlap in their incidences. -

CEPF EMI Newsletter Issue 17 December 2019

A regular update of news from CEPF's East Melanesian Islands Contact us Halo evriwan! In this final issue of the year, we share with you updates and stories from CEPF grantees active in the East Melanesian Islands. We invite you to share your project stories with us! FROM THE RIT RIT Team Planning The RIT recently came together in Fiji to join the IUCN Oceania Regional Office planning retreat, and to carry out their own strategic planning for 2020. The team mapped out priorities for training, capacity building, and filling gaps in funding over the final 18 months of CEPF’s investment in East Melanesia. The team also received refresher training on CEPF processes including finances, and spent time reviewing the Letters of Inquiry received in the most recent Call for Proposals. Please send the team your plans for field and project activities in 2020, so that we can arrange to meet and support you better! Vatu Molisa, Vanuatu; Zola Sangga, PNG; Ravin Dhari, Solomon Islands; Helen Pippard New grants in process Three new small grants were contracted by IUCN in Q3 2019: Oceania Ecology Group for work on giant rats in Solomon Islands and Bougainville; Mai Maasina Green Belt, to build a conservation network in Malaita; and Eco-Lifelihood Development Associates, to strengthen the capacity of this group for biodiversity conservation in Vanuatu. A number of grants from previous calls are being finalised and are expected to be contracted in the next quarter. Following the latest, and possibly final, Call for Proposals in November 2019, CEPF and the RIT are now in the process of reviewing received LOIs. -

Choiseul Province, Solomon Islands

Ridges to Reefs Conservation Plan for Choiseul Province, Solomon Islands Geoff Lipsett-Moore, Richard Hamilton, Nate Peterson, Edward Game, Willie Atu, Jimmy Kereseka, John Pita, Peter Ramohia and Catherine Siota i Published by: The Nature Conservancy, Asia-Pacific Resource Centre Contact Details: Geoff Lipsett-Moore: The Nature Conservancy, 51 Edmondstone Street, South Brisbane. Qld. 4101. Australia email: [email protected] William Atu: The Nature Conservancy, PO Box 759, Honiara, Solomon islands. e-mail: [email protected] Suggested Citation: Geoff Lipsett-Moore, Richard Hamilton, Nate Peterson, Edward Game, Willie Atu, Jimmy Kereseka, John Pita, Peter Ramohia and Catherine Siota (2010). Ridges to Reefs Conservation Plan for Choiseul Province, Solomon Islands. TNC Pacific Islands Countries Report No. 2/10. 53 pp © 2010, The Nature Conservancy All Rights Reserved. Reproduction for any purpose is prohibited without prior permission Available from: Asia-Pacific Resource Centre The Nature Conservancy 51 Edmondstone Street South Brisbane, Queensland 4101 Australia Or via the worldwide web at: http://conserveonline.org/workspaces/pacific.island.countries.publications/documents/choiseul ii iii Foreword The land and seas surrounding Lauru are the life-blood of our people, and our long term survival and prosperity is integrally linked to the ecological health of our small island home. Our ancestors’ were acutely aware of this, and they developed many intricate customs and traditions relating to the ownership and use of Lauru’s natural resources. Although many of our worthy traditions and customs persist, today our island of Lauru is faced with a growing number of threats. Rapid population growth and our entry into the global cash economy have dramatically increased pressure on our natural resources.