Introductory Comment

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

What's Inside

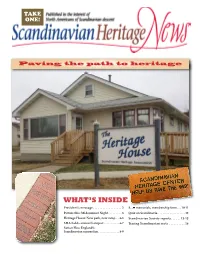

TAKE ONE! June 2014 Paving the path to heritage WHAT’S INSIDE President’s message . 2 SHA memorials, membership form . 10-11 Picture this: Midsummer Night . 3 Quiz on Scandinavia . 12 Heritage House: New path, new ramp . 4-5 Scandinavian Society reports . 13-15 SHA holds annual banquet . 6-7 Tracing Scandinavian roots . 16 Sutton Hoo: England’s Scandinavian connection . 8-9 Page 2 • June 2014 • SCANDINAVIAN HERITAGE NEWS President’s MESSAGE Scandinavian Heritage News Vol. 27, Issue 67 • June 2014 Join us for Midsummer Night Published quarterly by The Scandinavian Heritage Assn . by Gail Peterson, president man. Thanks to 1020 South Broadway Scandinavian Heritage Association them, also. So far 701/852-9161 • P.O. Box 862 we have had sev - Minot, ND 58702 big thank you to Liz Gjellstad and eral tours for e-mail: [email protected] ADoris Slaaten for co-chairing the school students. Website: scandinavianheritage.org annual banquet again. Others on the Newsletter Committee committee were Lois Matson, Ade - Midsummer Gail Peterson laide Johnson, Marion Anderson and Night just ahead Lois Matson, Chair Eva Goodman. (See pages 6 and 7.) Our next big event will be the Mid - Al Larson, Carroll Erickson The entertainment for the evening summer Night celebration the evening Jo Ann Winistorfer, Editor consisted of cello performances by Dr. of Friday, June 20, 2014. It is open to 701/487-3312 Erik Anderson (MSU Professor of the public. All of the Nordic country [email protected] Music) and Abbie Naze (student at flags will be flying all over the park. Al Larson, Publisher – 701/852-5552 MSU). -

EUI Working Papers

ROBERT SCHUMAN CENTRE FOR ADVANCED STUDIES EUI Working Papers RSCAS 2010/75 ROBERT SCHUMAN CENTRE FOR ADVANCED STUDIES EUDO Citizenship Observatory DUAL CITIZENSHIP FOR TRANSBORDER MINORITIES? HOW TO RESPOND TO THE HUNGARIAN-SLOVAK TIT-FOR-TAT Edited by Rainer Bauböck EUROPEAN UNIVERSITY INSTITUTE, FLORENCE ROBERT SCHUMAN CENTRE FOR ADVANCED STUDIES EUROPEAN UNION DEMOCRACY OBSERVATORY ON CITIZENSHIP Dual citizenship for transborder minorities? How to respond to the Hungarian-Slovak tit-for-tat EDITED BY RAINER BAUBÖCK EUI Working Paper RSCAS 2010/75 This text may be downloaded only for personal research purposes. Additional reproduction for other purposes, whether in hard copies or electronically, requires the consent of the author(s), editor(s). If cited or quoted, reference should be made to the full name of the author(s), editor(s), the title, the working paper, or other series, the year and the publisher. ISSN 1028-3625 © 2010 Edited by Rainer Bauböck Printed in Italy, October 2010 European University Institute Badia Fiesolana I – 50014 San Domenico di Fiesole (FI) Italy www.eui.eu/RSCAS/Publications/ www.eui.eu cadmus.eui.eu Robert Schuman Centre for Advanced Studies The Robert Schuman Centre for Advanced Studies (RSCAS), created in 1992 and directed by Stefano Bartolini since September 2006, aims to develop inter-disciplinary and comparative research and to promote work on the major issues facing the process of integration and European society. The Centre is home to a large post-doctoral programme and hosts major research programmes and projects, and a range of working groups and ad hoc initiatives. The research agenda is organised around a set of core themes and is continuously evolving, reflecting the changing agenda of European integration and the expanding membership of the European Union. -

The King's Nation: a Study of the Emergence and Development of Nation and Nationalism in Thailand

THE KING’S NATION: A STUDY OF THE EMERGENCE AND DEVELOPMENT OF NATION AND NATIONALISM IN THAILAND Andreas Sturm Presented for the Degree of Doctor of Philosophy of the University of London (London School of Economics and Political Science) 2006 UMI Number: U215429 All rights reserved INFORMATION TO ALL USERS The quality of this reproduction is dependent upon the quality of the copy submitted. In the unlikely event that the author did not send a complete manuscript and there are missing pages, these will be noted. Also, if material had to be removed, a note will indicate the deletion. Dissertation Publishing UMI U215429 Published by ProQuest LLC 2014. Copyright in the Dissertation held by the Author. Microform Edition © ProQuest LLC. All rights reserved. This work is protected against unauthorized copying under Title 17, United States Code. ProQuest LLC 789 East Eisenhower Parkway P.O. Box 1346 Ann Arbor, Ml 48106-1346 I Declaration I hereby declare that the thesis, submitted in partial fulfillment o f the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy and entitled ‘The King’s Nation: A Study of the Emergence and Development of Nation and Nationalism in Thailand’, represents my own work and has not been previously submitted to this or any other institution for any degree, diploma or other qualification. Andreas Sturm 2 VV Abstract This thesis presents an overview over the history of the concepts ofnation and nationalism in Thailand. Based on the ethno-symbolist approach to the study of nationalism, this thesis proposes to see the Thai nation as a result of a long process, reflecting the three-phases-model (ethnie , pre-modem and modem nation) for the potential development of a nation as outlined by Anthony Smith. -

A Companion to the French Revolution Peter Mcphee

WILEY- BLACKwELL COMPANIONS WILEY-BLACKwELL COMPANIONS TO EUROPEAN HISTORY TO EUROPEAN HISTORY EDIT Peter McPhee Wiley-blackwell companions to history McPhee A Companion to the French Revolution Peter McPhee Also available: e Peter McPhee is Professorial Fellow at the D BY University of Melbourne. His publications include The French Revolution is one of the great turning- Living the French Revolution 1789–1799 (2006) and points in modern history. Never before had the Robespierre: A Revolutionary Life (2012). A Fellow people of a large and populous country sought to of both the Australian Academy of the Humanities remake their society on the basis of the principles and the Academy of Social Sciences, he was made of popular sovereignty and civic equality. The a Member of the Order of Australia in 2012 for drama, success, and tragedy of their endeavor, and service to education and the discipline of history. of the attempts to arrest or reverse it, have attracted scholarly debate for more than two centuries. the french revolution Contributors to this volume Why did the Revolution erupt in 1789? Why did Serge Aberdam, David Andress, Howard G. Brown, it prove so difficult to stabilize the new regime? Peter Campbell, Stephen Clay, Ian Coller, What factors caused the Revolution to take Suzanne Desan, Pascal Dupuy, its particular course? And what were the Michael P. Fitzsimmons, Alan Forrest, to A Companion consequences, domestic and international, of Jean-Pierre Jessenne, Peter M. Jones, a decade of revolutionary change? Featuring Thomas E. Kaiser, Marisa Linton, James Livesey, contributions from an international cast of Peter McPhee, Jean-Clément Martin, Laura Mason, acclaimed historians, A Companion to the French Sarah Maza, Noelle Plack, Mike Rapport, Revolution addresses these and other critical Frédéric Régent, Barry M. -

E-Catalogue 16 Recent Acquisitions

♦ MUSINSKY RARE BOOKS ♦ E-Catalogue 16 Recent acquisitions No. 21 www.musinskyrarebooks.com + 1 212 579-2099 [email protected] Powerful women having fun 1) ABBEY OF REMIREMONT – Kyriolés ou Cantiques Qui sont chantez à l'Eglise de Mesdames de Remiremont, par les jeunes filles de différentes Parroisses des Villages voisins de cette Ville, qui sont obligez d'y venir en procession le lendemain de la Pentecôte. Remiremont: chez Cl[aude] Nic[olas] Emm[anuel] Laurent, 1773. 8vo (185 x 115 mm). [3], 4-14, [2] pp. Four large woodcuts, printed one to a page on the first and last leaves, within various woodcut and typographic ornamental borders. Woodcut headpiece, type ornaments. Dark green 19th-century quarter morocco, pale green paper flyleaves. $3400 ONLY EDITION, an unusual piece of popular printing, memorializing an ancient religious ritual held yearly on Pentecost Monday at the female Abbey of Remiremont in the Vosges. This ancient establishment had been founded in the 7th century as a double monastery of monks and nuns, under the austere rule of Saint Columbanus, by Saints Amé (or Aimé) and Romaric, who served successively as its first abbots. The mens’ monastery disappeared early on, and in the early 9th century the nuns embraced the more flexible Benedictine rule. The Abbey gradually became a secularized elite institution, reserved for women who could prove sixteen quarters of nobility on both paternal and maternal sides. These exigences were common to several other aristocratic chapters in Lorraine, but Remiremont was the richest of all the Lorraine abbeys, and its chanoinesses, known as les Dames de Remiremont, enjoyed all the privileges of a secular life, including marriage, and shared in the Abbey’s considerable income. -

Read Book What Is a Child?

WHAT IS A CHILD? PDF, EPUB, EBOOK Beatrice Alemagna | 36 pages | 20 Sep 2016 | TATE PUBLISHING | 9781849764124 | English | London, United Kingdom What is a Child? PDF Book Audio help More spoken articles. In other states, it has to be proven that the drugs were used in the presence of the child. Minor Age of majority. The Issue What is Child Abuse? Retrieved 9 October Examples of medical neglect: Not taking child to hospital or appropriate medical professional for serious illness or injury Keeping a child from getting needed treatment Not providing preventative medical and dental care Failing to follow medical recommendations for a child Educational Neglect Parents and schools share responsibility for making sure children have access to opportunities for academic success. We have a free legal aid directory here. They must also provide basic preventive care to make sure their child stays safe and healthy. Ken discusses how the relationship between parent and child must evolve as the child ages, and how any theory of parental authority must take that into account. Is the word kid slang? Social Forces, Vol. The awkward case of 'his or her'. Children Paternalism Family Ethics. Ken points out that there are two main ways to consider children--in terms of the differences between children and adults from a developmental perspective, and questions concerning the moral status of children compared to adults. Listen to this article. In some cases, both the offender and the victim may be removed from the home. Join John and Ken as they reflect on the nature of childhood. This is also known as Munchhausen by Proxy. -

Dyeing Sutton Hoo Nordic Blonde: an Interpretation of Swedish Influences on the East Anglian Gravesite

DYEING SUTTON HOO NORDIC BLONDE: AN INTERPRETATION OF SWEDISH INFLUENCES ON THE EAST ANGLIAN GRAVESITE Casandra Vasu A Thesis Submitted to the Graduate College of Bowling Green State University in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of MASTER OF ARTS August 2008 Committee: Andrew Hershberger, Advisor Charles E. Kanwischer © 2008 Casandra Vasu All Rights Reserved iii ABSTRACT Andrew Hershberger, Advisor Nearly seventy years have passed since the series of tumuli surrounding Edith Pretty’s estate at Sutton Hoo in Eastern Suffolk, England were first excavated, and the site, particularly the magnificent ship-burial and its associated pieces located in Mound 1, remains enigmatic to archaeologists and historians. Dated to approximately the early seventh century, the Sutton Hoo entombment retains its importance by illuminating a period of English history that straddles both myth and historical documentation. The burial also exists in a multicultural context, an era when Scandinavian influences factored heavily upon society in the British Isles, predominantly in the areas of art, religion and literature. Literary works such as the Old English epic of Beowulf, a tale of a Geatish hero and his Danish and Swedish counterparts, offer insight into the cultural background of the custom of ship-burial and the various accoutrements of Norse warrior society. Beowulf may hold an even more specific affinity with Sutton Hoo, in that a character from the tale, Weohstan, is considered to be an ancestor of the man commemorated in the ship- burial in Mound 1. Weohstan, whose allegiance lay with the Geats, was nonetheless a member of the Wægmunding clan, distant relations to the Swedish Scylfing dynasty. -

Anti-Oedipus: Capitalism and Schizophrenia Free Download

ANTI-OEDIPUS: CAPITALISM AND SCHIZOPHRENIA FREE DOWNLOAD Professor Gilles Deleuze,Felix Guattari,Michel Foucault,Mark Seem,Robert Hurley | 400 pages | 26 May 2009 | Penguin Putnam Inc | 9780143105824 | English | New York, NY, United States Capitalism and Schizophrenia Experientially, the effects of such substances can include a loosening relative deterritorialization of the worldview of the user i. London: Allen Lane. Sep 11, pat rated it it was amazing. Schizoanalysis seeks to show how "in the subject who desires, desire can be made to desire its own repression —whence the role of the Anti-Oedipus: Capitalism and Schizophrenia instinct in the circuit connecting desire to the social sphere. This was both an unforgettable and an elusive read, one that I'm sure I will go back to again and again. We are experiencing technical difficulties. The cosmos may be ultimately a projection of chaos, but it is still a natural movement of desire. I strongly suspect psychoanalyst Anti-Oedipus: Capitalism and Schizophrenia not like this book, even though the authors are using psychoanalysis in their critique. And here Anti-Oedipus: Capitalism and Schizophrenia have the universality of structuralism, of myth, capital, Oedipus. Children with Emerald Eyes. More Details Sign in. Guattari developed the implications of their theory for a concrete political project in his book with the Italian autonomist marxist philosopher Antonio NegriCommunists Like Us And once they produce the one the phallus, the despotic signifierit becomes a really Anti-Oedipus: Capitalism and Schizophrenia force, so real that it appears as primary to the many. Fredric Jameson. Trained as a psychoanalyst, he, along with close friend and colleague Gilles Anti-Oedipus: Capitalism and Schizophrenia, were instrumental figures in the anti-psychiatry movement, which challenged established viewpoints in psychoanalysis, philosophy, and sociology. -

François Velde, Heraldica, Revived and Recently Created Orders Of

Revived and Recently Created Orders http://www.heraldica.org/topics/orders/bg-orders.htm Revived and Recently Created Orders of Chivalry Contents Introduction Revived Orders: Modern Templars Saint Thomas of Acre The British Order of Saint John The Order of the Militia of Christ The Order of Saint George of Burgundy The Modern Order of Saint Lazarus The Niadh Nask Recently Created Orders Introduction This page describes a few modern orders of knighthood, which are either recreations of specific medieval orders, or imitations of medieval or monarchical orders without specific reference to any one. The term "bogus" is one I don't like, because it was so abused by Arthur Fox-Davies, who thought that any arms which were not delivered on parchment by a royal official were "bogus"; thus relegating 90% of heraldry into inexistence. As far as I am concerned, there is no good reason why anyone could not create "orders of chivalry" today; how seriously such associations would be taken will depend on many factors, such as their membership, stated goals and veritable activities; but also on what they claim to be. Only people who would reject as "bogus" any such organization might be offended by the choice of certain orders. I discuss the general question of legitimacy of orders separately. I discuss two kinds of orders, revived and recently created. I use the term revived to refer to associations which call themselves orders of chivalry but are the only ones to do so, and which also claim to be identical with or directly emanated from well-defined historical orders of chivalry. -

|||GET||| Aspects of the Analysis of Family Structure 1St Edition

ASPECTS OF THE ANALYSIS OF FAMILY STRUCTURE 1ST EDITION DOWNLOAD FREE Ansley Johnson Coale | 9780691624464 | | | | | Historical Analysis of the Family Means, S. Risks and Problem Behaviors in Adolescence1— Research by the Pew Research Center shows that many parents—25 percent in. In all subsequent analyses age and gender were entered as covariates. Urbanism is a way of life. Get This Book. Therefore, higher levels of enmeshment compared to disengagement result in an upward adjustment of cohesion scores while a higher level of disengagement compared to enmeshment results in a downward adjustment of family cohesion scores. A recent Institute of Aspects of the Analysis of Family Structure 1st edition and National Research Council report on the early childhood workforce Institute of Medicine and National Research Council, illustrates the heightened focus not only on whether young children have opportunities to be exposed to healthy environments and supports but also on the people who provide those supports. However, the type of functioning evident in a family may equally influence youth outcomes. Pedigree chart Ahnentafel Genealogical numbering systems Seize quartiers Quarters of nobility. For instance, in Indiathe family is a patriarchal society, with the sons' families often staying in the same house. Consider single men. Barrett, A. Visit NAP. Nelson, C. We all know stable and loving single-parent families. The house often has a large reception area and a common kitchen. Page 31 Share Cite. Comparative Studies in Society and History , 15 ,3— In modern Western cultures dominated by immediate family constructs, the term has come to be used generically to refer to grandparents, uncles, aunts, and cousins, whether they live together within the same household or not. -

University Microfiims 300 North Zeeb Road Ann Arl>Or

INFORMATION TO USERS This dissertation was produced from a microfilm copy of the original document. While the most advanced technological means to photograph and reproduce this document have been used, the quality is heavily dependent upon the quality of the original submitted. The following explanation of techniques is provided to help you understand markings or patterns which may appear on this reproduction. 1. The sign or "target" for pages apparently lacking from the document photographed is "Missing Page(s)". If it was possible to obtain the missing page(s) or section, they are spliced into the film along with adjacent pages. This may have necessitated cutting thru an image and duplicating adjacent pages to insure you complete continuity. 2. When an image on the film is obliterated with a large round black mark, it is an indication that the photographer suspected that the copy may have moved during exposure and thus cause a blurred image. You will find a good image of the page in the adjacent frame. 3. When a map, drawing or chart, etc., was part of the material being photographed the photographer followed a definite method in "sectioning" the material. It is customary to begin photoing at the upper left hand comer of a large sheet and to continue photoing from left to right in equal sections with a small overlap. If necessary, sectioning is continued again — beginning below the first row and continuing on until complete. 4. The majority of users indicate that the textual content is of greatest value, however, a somewhat higher quality reproduction could be made from "photographs" if essential to the understanding of the dissertation. -

In Search of the Gentilshommes Campagnards: Noble Diversity and Social Structure in Burgundy, 1682-1789

In Search of the gentilshommes campagnards: Noble Diversity and Social Structure in Burgundy, 1682-1789 Susan Carr St Andrews Studies in French History and Culture ST ANDREWS STUDIES IN FRENCH HISTORY AND CULTURE The history and historical culture of the French-speaking world is a major field of interest among English-speaking scholars. The purpose of this series is to publish a range of shorter monographs and studies, between 25,000 and 50,000 words long, which illuminate the history of this community of peoples between the later Middle Ages and the late twentieth century. The series covers the full span of historical themes relating to France: from political history, through military/naval, diplomatic, religious, social, financial, gender, cultural and intellectual history, art and architectural history, to historical literary culture. Titles in the series are rigorously peer-reviewed through the editorial board and external assessors, and are published as both e-books and paperbacks. Editorial Board Professor Guy Rowlands, University of St Andrews (Editor-in-Chief) Professor Andrew Pettegree, University of St Andrews Professor Andrew Williams, University of St Andrews Dr Sarah Easterby-Smith, University of St Andrews Dr David Evans, University of St Andrews Dr Justine Firnhaber-Baker, University of St Andrews Dr Linda Goddard, University of St Andrews Dr Julia Prest, University of St Andrews Dr Bernhard Struck, University of St Andrews Dr Stephen Tyre, University of St Andrews Dr Akhila Yechury, University of St Andrews Professor Peter