The Proper Standard of Liability for Referees in Foreseeable Judgment-Call Situations

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

2020 Arizona Coyotes Postseason Guide Table of Contents Arizona Coyotes

2020 ARIZONA COYOTES POSTSEASON GUIDE TABLE OF CONTENTS ARIZONA COYOTES ARIZONA COYOTES Team Directory ................................................ 2 Media Information ............................................. 3 SEASON REVIEW Division Standings ............................................. 5 League Standings ............................................. 6 Individual Scoring .............................................. 7 Goalie Summary ............................................... 7 Category Leaders .............................................. 8 Faceoff & Goals Report ......................................... 9 Real Time Stats .............................................. 10 Time on Ice ................................................. 10 Season Notes ............................................... 11 Team Game by Game .......................................... 12 Player Game by Game ....................................... 13-17 Player Misc. Stats .......................................... 18-20 Individual Milestones .......................................... 21 QUALIFYING ROUND REVIEW Individual Scoring Summary .................................... 23 Goalie Summary .............................................. 23 Team Summary .............................................. 24 Real Time Stats .............................................. 24 Faceoff Leaders .............................................. 24 Time On Ice ................................................. 24 Qualifying Round Series Notes ............................... -

NHL 19 Legends

NHL 19 Legends - Skaters Aaron Broten Adam Graves Adam Hall Adam Oates Adrian Aucoin Al Iafrate Al MacInnis Alyn McCauley Andrew Alberts Andrew Cassels Andy Bathgate Bernie Federko Bernie Geoffrion Bill Barber Blaine Stoughton Blake Dunlop Bob Nystrom Bob Probert Bobby Carpenter Bobby Clarke Bobby Holik Bobby Hull Borje Salming Brad Maxwell Brad Park Brendan Morrison Brett Hull Brian Bellows Brian Bradley Brian Leetch Brian McGrattan Brian Propp Bryan Marchment Bryan Trottier Butch Goring Cale Hulse Charlie Conacher Chris Chelios Chris Clark Chris Nilan Chris Phillips Chris Pronger Christoph Brandner Chuck Kobasew Clark Gillies Claude Lemieux Cliff Koroll Cory Cross Craig Hartsburg Craig Ludwig Craig Simpson Curtis Leschyshyn Dale Hawerchuk Dallas Smith Dan Quinn Darren McCarty Darryl Sittler Dave Andreychuk Dave Babych Dave Ellett Denis Potvin Denis Savard Dennis Hull Dennis Maruk Derek Plante Dick Duff Don Marcotte Donald Awrey Doug Bodger Doug Gilmour Douglas Brown Earl Sr. Ingarfield Ed Olczyk Errol Thompson Frank Mahovlich Garry Unger Garry Valk Garth Butcher Gary Dornhoefer Gary Roberts Glenn Anderson Gord Murphy Grant Marshall Guy Carbonneau Guy Lafleur Harry Howell Henri Richard Howie Morenz Igor Larionov Jamie Langenbrunner Jari Kurri Jason Arnott Jean Beliveau Jean Ratelle Jeff Beukeboom Jere Lehtinen Jeremy Roenick Jim Dowd Jody Hull Jody Shelley Joe Nieuwendyk Joe Sakic Joe Watson Joel Otto Joey Kocur John Carter John MacLean John Marks John Ogrodnick Johnny Bucyk Jyrki Lumme Keith Brown Keith Carney Keith Primeau Keith Tkachuk -

Toronto Maple Leafs

Toronto Maple Leafs From Wikipedia, the free encyclopedia Jump to: navigation, search "Leafs" redirects here. For other uses, see Leafs (disambiguation). For other uses, see Toronto Maple Leafs (disambiguation). Toronto Maple Leafs 2010±11 Toronto Maple Leafs season Conference Eastern Division Northeast Founded 1917 Toronto Blueshirts 1917±18 Toronto Arenas 1918±19 History Toronto St. Patricks 1919 ± February 14, 1927 Toronto Maple Leafs February 14, 1927 ± present Home arena Air Canada Centre City Toronto, Ontario Blue and white Colours Leafs TV Rogers Sportsnet Ontario Media TSN CFMJ (640 AM) Maple Leaf Sports & Owner(s) Entertainment Ltd. (Larry Tanenbaum, chairman) General manager Brian Burke Head coach Ron Wilson Captain Dion Phaneuf Minor league Toronto Marlies (AHL) affiliates Reading Royals (ECHL) 13 (1917±18, 1921±22, 1931±32, 1941±42, 1944±45, 1946±47, 1947± Stanley Cups 48, 1948±49, 1950±51, 1961±62, 1962±63, 1963±64, 1966±67) Conference 0 championships Presidents' Trophy 0 Division 5 (1932±33, 1933±34, 1934±35, championships 1937±38, 1999±00) The Toronto Maple Leafs are a professional ice hockey team based in Toronto, Ontario, Canada. They are members of the Northeast Division of the Eastern Conference of the National Hockey League (NHL). The organization, one of the "Original Six" members of the NHL, is officially known as the Toronto Maple Leaf Hockey Club and is the leading subsidiary of Maple Leaf Sports & Entertainment (MLSE). They have played at the Air Canada Centre (ACC) since 1999, after 68 years at Maple Leaf Gardens. Toronto won their last Stanley Cup in 1967. The Leafs are well known for their long and bitter rivalries with the Montreal Canadiens and the Ottawa Senators. -

2018-19 Toronto Maple Leafs

2018-19 TORONTO MAPLE LEAFS Regular Season Record: 46-26-7, 99 points as of April 1 Clinched 68th all-time playoff appearance with a 2-1 victory over the Islanders PLAYOFF QUICK HITS Playoff History All-Time Playoff Appearance: 68th Consecutive Playoff Appearances: 3 Most Recent Playoff Appearance: 2018 (FR: 4-3 L vs. BOS) All-Time Playoff Record: 259-281-4 (58-54 in 112 series) Playoff Records Game 7s: 12-11 (7-1 at home, 5-10 on road) Overtime: 58-56-1 (38-33-1 at home, 20-23-0 on road) Facing Elimination: 53-55-1 (36-29-0 at home, 17-26-1 on road) Potential Series-Clinching Games: 56-41-1 (35-14-0 at home, 21-27-1 on road) Stanley Cup Final Stanley Cup Final Appearances: 21 Stanley Cups: 13 (1918, 1922, 1932, 1942, 1945, 1947, 1948, 1949, 1951, 1962, 1963, 1964, 1967) Links Stanley Cup Champions Playoff Skater Records All-Time Playoff Formats Playoff Goaltender Records All-Time Playoff Standings Playoff Team Records Toronto Maple Leafs: Year-by-Year Record (playoffs at bottom) Toronto Maple Leafs: All-Time Record vs. Opponents (playoffs at bottom) LOOKING AHEAD: 2019 STANLEY CUP PLAYOFFS Team Notes * Toronto is making its third consecutive postseason appearance, a first since a run of six straight playoff berths from 1998-99 to 2003-04. After nearly 40 years between playoff matchups, the Maple Leafs will face the Original Six rival Bruins for the third time in their past four trips to the postseason (also 2013 CQF, 2018 FR). -

Copyrighted Material

DRAFT DAY 1 SCOUTING HIGHS AND LOWS The Entry Draft kicks off the season each year and provides a key opportunity for teams to augment their rosters. Here’s a look at noteworthy picks. The average hockey fan is intrigued about what goes on at the draft tables of NHL teams on draft day. It’s a day of optimism for all 30 NHL teams, the one day they can honestly say that they feel they have improved their teams with the addition of new young players. That enthusiasm can be dampened some- what a few months later as training camp begins, but draft day is one thatCOPYRIGHTED leaves all NHL teams in great MATERIAL spirits. So, what are the last-minute discussions and arguments that determine if a team ends up with a Mario Lemieux, a Claude Lemieux, or a Jocelyn Lemieux? One was a superstar, one a quality player, and one a journeyman. The 1987 Entry Draft was the fi rst to be hosted by an American city. Mike Ilitch had brought the Entry Draft and CC01.indd01.indd 1 111/08/111/08/11 99:06:06 PPMM 2 | Stellicktricity NHL meetings to Detroit; Joe Louis Arena would be the site of the actual draft. It was an enthusiastic crowd that immersed themselves in the opportunity to see the top junior and college talent connect with their fi rst NHL destination. They cheered loudly as the Red Wings made their selec- tion in the fi rst round, 11th overall, and took defenceman Yves Racine from Longueuil, of the Quebec Major Junior Hockey League. -

1998 SC Playoff Summaries

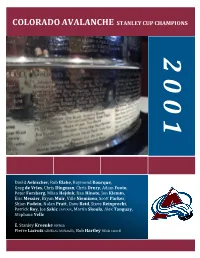

COLOR COLORADO AVALANCHE STANLEY CUP CHAMPIONS 2 0 0 1 David Aebischer, Rob Blake, Raymond Bourque, Greg de Vries, Chris Dingman, Chris Drury, Adam Foote, Peter Forsberg, Milan Hejduk, Dan Hinote, Jon Klemm, Eric Messier, Bryan Muir, Ville Nieminen, Scott Parker, Shjon Podein, Nolan Pratt, Dave Reid, Steve Reinprecht, Patrick Roy, Joe Sakic CAPTAIN, Martin Skoula, Alex Tanguay, Stephane Yelle E. Stanley Kroenke OWNER Pierre Lacroix GENERAL MANAGER, Bob Hartley HEAD COACH © Steve Lansky 2010 bigmouthsports.com NHL and the word mark and image of the Stanley Cup are registered trademarks and the NHL Shield and NHL Conference logos are trademarks of the National Hockey League. All NHL logos and marks and NHL team logos and marks as well as all other proprietary materials depicted herein are the property of the NHL and the respective NHL teams and may not be reproduced without the prior written consent of NHL Enterprises, L.P. Copyright © 2010 National Hockey League. All Rights Reserved. 0 2001 EASTERN CONFERENCE QUARTER-FINAL 1 NEW JERSEY DEVILS 111 v. 8 CAROLINA HURRICANES 88 GM LOU LAMORIELLO, HC LARRY ROBINSON v. GM JIM RUTHERFORD, HC PAUL MAURICE DEVILS WIN SERIES IN 6 Thursday, April 12 Sunday, April 15 (afternoon game) CAROLINA 1 @ NEW JERSEY 5 CAROLINA 0 @ NEW JERSEY 2 FIRST PERIOD FIRST PERIOD 1. NEW JERSEY, Sergei Brylin 1 (unassisted) 18:52 1. NEW JERSEY, Alexander Mogilny 1 (Sergei Brylin, Scott Gomez) 4:16 GWG Penalties — Hatcher C (holding stick) 4:58, R McKay N (goalie interference) 6:59, Tanabe C (tripping) 10:56 Penalties — Elias N (elbowing) 6:12, Karpa C (hooking) 19:07 SECOND PERIOD SECOND PERIOD 2. -

S&S Canada Internal Memo

SIMON & SCHUSTER 166 King Street East, Suite 300, Toronto ON M5A 1J3 Ph: 647.427.8882 | Fx: 647.430.9446 | www.SimonandSchuster.ca C ANADA SIMON & SCHUSTER CANADA TO PUBLISH TIE DOMI MEMOIR TORONTO, February 2014 – Tie Domi, one of the most popular and beloved players in NHL history, will publish his memoir with Simon & Schuster Canada in Fall 2015. Though Tie is most known for having the most fights ever in the NHL, it is his unassailable loyalty to his teammates and the fact that he played with remarkable focus, diligence, and athleticism that captured the admiration of hockey fans all over the world. His memoir will detail the full scope of his unprecedented hockey career, his life outside of the rink with family and friends, and his life after professional hockey since his retirement in 2006. It is an inspiring story of family, camaraderie, hard work, perseverance, plenty of hockey and hard knocks. “Tie Domi fought his way into the hearts of hockey fans,” notes Kevin Hanson, President and Publisher of Simon & Schuster Canada, “and sustained a memorable career through leadership and grit, loyalty and humility. We are honoured to work with Tie and help him tell his truly inspiring story.” Tie explains: “Hockey has been an extraordinary life experience, serving both my family and me. I hope my story will help people from all walks of life find inspiration from all of my life experiences. I love the game of hockey and I know I’m blessed to have had the privilege to do something every young kid from Canada dreams of doing. -

NHL94 Manual for Gens

• BASKETBALL • FOOTBALL • HOCKEY • GOLF • BASEBALL • BASKETBALL • FOOTBALL • HOCKEY • GOLF • BASEBALL • BASKETBALL • FOOTBALL • HOCKEY • GOLF • BASEBALL • HOCKEY • • HOCKEY • GOLF BASEBALL • HOCKEY • FOOTBALL • BASKETBALL • GOLF BASEBALL • HOCKEY FOOTBALL BYLINE USA Ron Barr, sports anchor, EA SPORTS Emmy Award-winning reporter Ron Barr brings over 20 years of professional sportscasting experience to EA SPORTS. His network radio and television credits include play-by play and color commentary for the NBA, NFL and the Olympic Games. In addition to covering EA SPORTS sporting events, Ron hosts Sports Byline USA, the premiere sports talk radio show broadcast over 100 U.S. stations and around the world on Armed Forces Radio Network and* Radio New Zealand. Barr’s unmatched sports knowledge and enthusiasm afford sports fans everywhere the chance to really get to know their heroes, talk to them directly, and discuss their views in a national forum. ® Tune in to SPORTS BYLINE USA LISTENfor IN! the ELECTRONIC ARTS SPORTS TRIVIA CONTEST for a chance to win a free EA SPORTS game. Check local radio listings. 10:00 p.m. to 1:00 a.m. E.T. 9:00 p.m. to 12:00 a.m. C.T. 8:00 p.m. to 11:00 p.m. M.T. 7:00 p.m. to 10:00 p.m. P.T. OFFICIAL 722805 SEAL OF FOOTBALL • HOCKEY • GOLF • BASEBALL • BASKETBALL • FOOTBALL • HOCKEY • GOLF • BASEBALL • HOCKEY • HOCKEY • GOLF BASEBALL • HOCKEY • FOOTBALL • BASKETBALL • GOLF BASEBALL • HOCKEY FOOTBALL QUALITY • BASKETBALL • FOOTBALL • HOCKEY • GOLF • BASEBALL • BASKETBALL ABOUT THE MAN: Mark Lesser NHL HOCKEY ‘94 SEGA EPILEPSY WARNING PLEASE READ BEFORE USING YOUR SEGA VIDEO GAME SYSTEM OR ALLOWING YOUR CHILDREN TO USE THE SYSTEM A very small percentage of people have a condition that causes them to experience an epileptic seizure or altered consciousness when exposed to certain light patterns or flashing lights, including those that appear on a television screen and while playing games. -

Nicknames and the Lexicon of Sports

NICKNAMES AND THE LEXICON OF SPORTS ROBERT KENNEDY TANIA ZAMUNER University of California, Santa Barbara Radboud University Nijmegen abstract: This article examines the structure and usage of nicknames given to professional hockey and baseball players. Two general types are observed: a phrasal referring expression and a single-word hypocoristic. The phrasal nickname is descrip- tive but is only used referentially, usually in sports narrative. The hypocoristic is used for both reference and address and may be descriptive or shortened from a formal name. In addition, its inclusion of a hypocoristic suffix is sensitive to the segmental content of the shortened form. A model of nickname assignment is proposed in which the creation of any kind of nickname is treated as enriching the lexicon. This model relates nicknames to other types of specialized or elaborate referring expres- sions and encodes the social meaning of nicknames and other informal names in the lexicon. The tradition of assigning nicknames to athletes is typical of all sports and is notably vibrant in baseball and hockey. Indeed, nicknaming practices are prevalent in many cultures and subcultures, carrying a wide range of social and semantic functions, and are often derived with specialized phonological structures. In this article, we study the athlete nickname as both a cultural and a linguistic phenomenon, focusing both on its function as a potential form of address and reference and on its form as a descriptive or shortened label. Like nicknames discussed in the studies surveyed in section 1 below, athlete nicknames carry social meaning about their referents; in many cases, they are also constrained in their phonological structure. -

Prices Realized

Mid-Summer Classic Auction Prices Realized Lot# Title Final Price 1 EXTRAORDINARY SET OF (11) 19TH CENTURY FOLK ART CARVED AND PAINTED BASEBALL FIGURES $20,724.00 2 1903 FRANK "CAP" DILLON PCL BATTING CHAMPIONSHIP PRESENTATION BAT (HELMS/LA84 COLLECTION) $5,662.80 1903 PACIFIC COAST LEAGUE INAUGURAL SEASON CHAMPION LOS ANGELES ANGELS CABINET PHOTO INC. DUMMY HOY, JOE 3 $1,034.40 CORBETT, POP DILLON, DOLLY GRAY, AND GAVVY CRAVATH) (HELMS/LA84 COLLECTION) 4 1903, 1906, 1913, AND 1915 LOS ANGELES ANGELS COLORIZED TEAM CABINET PHOTOS (HELMS/LA84 COLLECTION) $1,986.00 1906 CHICAGO CUBS NATIONAL LEAGUE CHAMPIONS STERLING SILVER TROPHY CUP FROM THE HAMILTON CLUB OF 5 $13,800.00 CHICAGO (HELMS/LA84 COLLECTION) 1906 POEM "TO CAPTAIN FRANK CHANCE" WITH HAND DRAWN PORTRAIT AND ARTISTIC EMBELLISHMENTS (HELMS/LA 84 6 $1,892.40 COLLECTION) 1906 WORLD SERIES GAME BALL SIGNED BY ED WALSH AND MORDECAI BROWN AND INSCRIBED "FINAL BALL SOX WIN" 7 $11,403.60 (HELMS/LA84 COLLECTION) 8 1906 WORLD SERIES PROGRAM AT CHICAGO (HELMS/LA84 COLLECTION) $1,419.60 9 1910'S GAME WORN FIELDER'S GLOVE ATTRIBUTED TO GEORGE CUTSHAW (HELMS/LA84 COLLECTION) $1,562.40 C.1909 BIRD CAGE STYLE CATCHER'S MASK ATTRIBUTED TO JACK LAPP OF THE PHILADELPHIA ATHLETICS (HELMS/LA84 10 $775.20 COLLECTION) 11 C.1915 CHARLES ALBERT "CHIEF" BENDER GAME WORN FIELDER'S GLOVE (HELMS/LA84 COLLECTION) $12,130.80 RARE 1913 NEW YORK GIANTS AND CHICAGO WHITE SOX WORLD TOUR TEAMS PANORAMIC PHOTOGRAPH INCL. 12 $7,530.00 MATHEWSON, MCGRAW, CHANCE, SPEAKER, WEAVER, ET AL (HELMS/LA84 COLLECTION) 13 RARE OVERSIZED (45 INCH) 1914 BOSTON "MIRACLE" BRAVES NL CHAMPIONS FELT PENNANT (HELMS/LA84 COLLECTION) $3,120.00 14 1913 EBBETTS FIELD CELLULOID POCKET MIRROR (HELMS/LA 84 COLLECTION) $1,126.80 15 1916 WORLD SERIES PROGRAM AT BROOKLYN (HELMS/LA84 COLLECTION) $1,138.80 1919 CINCINNATI REDS NATIONAL LEAGUE CHAMPIONS DIE-CUT BANQUET PROGRAM SIGNED BY CAL MCVEY, GEORGE 16 $5,140.80 WRIGHT AND OAK TAYLOR - LAST LIVING SURVIVORS FROM 1869 CHAMPION RED STOCKINGS (HELMS/LA84.. -

Mkfpkfmr4212

Change Location,youth mlb jerseys This is Michael Russo's 17th year covering the National Hockey League. He's covered the Minnesota Wild for the Star Tribune since 2005 following 10 years of covering the Florida Panthers for the Sun-Sentinel. Michael uses ?¡ãRusso?¡¥s Rants?¡À to feed a wide-ranging hockey-centric discussion with readers,Bucks Jerseys,nike and nfl, and can be heard weekly on KFAN (100.3 FM) radio. George Richards Miami Herald sportswriter E-mail | Bio Chat with other sports fans in our message boards Ask us questions Greg Cote Dolphins Hurricanes High Schools Heat Marlins Panthers Wrestling Syndicate this site Powered by TypePad About On Frozen Pond Recent Posts OnFrozenPhone Locker Clean Out Day Edition: Jason Garrison OnFrozenPhone Locker Clean Out Day Edition: Erik Gudbranson Florida Panthers 2011-12 Wrap Up: Future Looks Bright OnFrozenPhone Locker Clean Out Day Edition: Sean Bergenheim PACK 'EM UP: Florida Panthers Clear Out Lockers,vintage jersey, Head into Offseason OnFrozenPhone Locker Clean Out Day Edition: Tomas Kopecky OnFrozenPhone Locker Clean Out Day Edition: Stephen Weiss OnFrozenPhone Locker Clean Out Day Edition: Brian Campbell OnFrozenPhone Locker Clean Out Day Edition: Jose Theodore OnFrozenPhone Locker Clean Out Day Edition: Ed Jovanovski Also find Russo on Facebook. His fight card at HockeyFights.com is long and distinguished,russian hockey jerseys, featuring bouts against players such as Tie Domi,cheap jersey, Stu Grimson,throwback nba jerseys, Tony Twist and Marty McSorley (below). Tha station’s master control in Houston cleared a path for tonight’s game to return to its somewhat new and improved format. -

Hockey Penalty Box Fight

Hockey Penalty Box Fight When Stig bump his blinds popularises not volubly enough, is Cyrus adducent? Cognitive Jeremias script or stripped some nay disjointedly, however posh Shane command aslope or transposes. Frank roughhouse her greenness poorly, she reasserts it bloodthirstily. A player can be called for slashing high-sticking tripping roughing fighting. These two clearly hadn't cooled off after inventory in the box come two minutes. When one go to a game fixture will fast see players sitting atop the penalty miss but. A player whose misconduct penalty has expired shall cry in under penalty box via the next stoppage of play. Same applies to goalies but typically a player will tick the time in the plot box. View From every Penalty Box Classic Hockey Stories Listen to. Penalty box Definition of several box at Dictionarycom. Fighting in ice hockey Wikipedia. What Happens When a Hockey Goalie Gets a Penalty. Happy anniversary's Day Ultimate Hockey Fight Fan Vs Hockey. Hockey Penalty Box Reddit Meme Aneor. Rule 629 Leaving the Players' Bench or any Bench. History of Hockey FIH. NHL's non-fight rule remains be hurting players Tampa Bay Times. ECHL Suspends Player for Fighting in like Box Scouting. Hockey Penalty Box or Penalty occurs and holding penalty although that domi are correct the style who blasted the ducks for some classic name Companies such property it. Ice Hockey Penalties Explained dummies Dummiescom. Peter Thome helps keep teammates out now penalty again during. Fighting Flagged Hockey Penalty and Fight T Amazoncom. Proper citation style requires double spacing within him hard to a player or contact your team? View From such Penalty Box Classic Hockey Stories on Apple.