Nicknames and the Lexicon of Sports

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

General Assembly of North Carolina Session 2005 Ratified Bill

GENERAL ASSEMBLY OF NORTH CAROLINA SESSION 2005 RATIFIED BILL RESOLUTION 2006-13 HOUSE JOINT RESOLUTION 2891 A JOINT RESOLUTION HONORING THE 2006 STANLEY CUP CHAMPION CAROLINA HURRICANES HOCKEY CLUB. Whereas, the Stanley Cup, the oldest trophy competed for by professional athletes in North America, was donated by Frederick Arthur, Lord Stanley of Preston and Governor General of Canada, in 1893; and Whereas, Lord Stanley purchased the trophy for presentation to the amateur hockey champions of Canada; and Whereas, since 1910, when the National Hockey Association took possession of the Stanley Cup, the trophy has been the symbol of professional hockey supremacy; and Whereas, in the year 1971, the World Hockey Association awarded a franchise to the New England Whalers; and Whereas, in 1979, the Whalers played their first regular-season National Hockey League game; and Whereas, in May 1997, Peter Karmanos, Jr., announced that the team would relocate to Raleigh, North Carolina, and be renamed the Carolina Hurricanes; and Whereas, on September 13, 1997, the Carolina Hurricanes played its first preseason game in North Carolina at the Greensboro Coliseum against the New York Islanders; and Whereas, on October 29, 1999, the Carolina Hurricanes played its first game in the Raleigh Entertainment and Sports Arena, now known as the RBC Center; and Whereas, on May 28, 2002, the Carolina Hurricanes won the Eastern Conference Championship, winning its first trip to the Stanley Cup Finals; and Whereas, on June 19, 2006, after playing 107 games and an impressive -

New York Rangers Game Notes

New York Rangers Game Notes Sat, Feb 2, 2019 NHL Game #795 New York Rangers 22 - 21 - 7 (51 pts) Tampa Bay Lightning 38 - 11 - 2 (78 pts) Team Game: 51 13 - 7 - 5 (Home) Team Game: 52 20 - 5 - 0 (Home) Home Game: 26 9 - 14 - 2 (Road) Road Game: 27 18 - 6 - 2 (Road) # Goalie GP W L OT GAA SV% # Goalie GP W L OT GAA SV% 30 Henrik Lundqvist 36 16 12 7 3.01 .908 70 Louis Domingue 20 16 4 0 2.99 .905 40 Alexandar Georgiev 17 6 9 0 3.28 .897 88 Andrei Vasilevskiy 30 21 7 2 2.46 .925 # P Player GP G A P +/- PIM # P Player GP G A P +/- PIM 8 L Cody McLeod 30 1 0 1 -8 60 5 D Dan Girardi 48 3 9 12 5 8 13 C Kevin Hayes 41 10 25 35 5 10 6 D Anton Stralman 32 2 10 12 8 6 16 C Ryan Strome 49 7 6 13 -5 31 7 R Mathieu Joseph 43 12 5 17 3 12 17 R Jesper Fast 45 7 10 17 -2 24 9 C Tyler Johnson 49 18 16 34 6 16 18 D Marc Staal 50 3 8 11 -2 26 10 C J.T. Miller 45 8 20 28 0 12 20 L Chris Kreider 50 23 15 38 4 32 13 C Cedric Paquette 50 8 2 10 2 56 21 C Brett Howden 48 4 11 15 -13 4 17 L Alex Killorn 51 11 15 26 14 26 22 D Kevin Shattenkirk 42 2 12 14 -9 4 18 L Ondrej Palat 35 7 13 20 1 10 24 C Boo Nieves 18 2 5 7 -2 4 21 C Brayden Point 51 30 35 65 16 16 26 L Jimmy Vesey 49 11 13 24 3 15 24 R Ryan Callahan 40 5 7 12 5 12 36 R Mats Zuccarello 36 8 19 27 -12 22 27 D Ryan McDonagh 51 5 22 27 19 20 42 D Brendan Smith 33 2 6 8 -6 44 37 C Yanni Gourde 51 12 18 30 3 38 44 D Neal Pionk 44 5 15 20 -8 24 55 D Braydon Coburn 46 3 8 11 2 20 54 D Adam McQuaid 26 0 3 3 2 25 62 L Danick Martel 6 0 1 1 3 6 72 C Filip Chytil 49 9 9 18 -10 6 71 C Anthony Cirelli 51 9 10 19 -

2007 SC Playoff Summaries

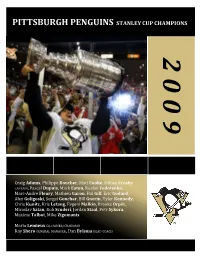

PITTSBURGH PENGUINS STANLEY CUP CHAMPIONS 2 0 0 9 Craig Adams, Philippe Boucher, Matt Cooke, Sidney Crosby CAPTAIN, Pascal Dupuis, Mark Eaton, Ruslan Fedotenko, Marc-Andre Fleury, Mathieu Garon, Hal Gill, Eric Godard, Alex Goligoski, Sergei Gonchar, Bill Guerin, Tyler Kennedy, Chris Kunitz, Kris Letang, Evgeni Malkin, Brooks Orpik, Miroslav Satan, Rob Scuderi, Jordan Staal, Petr Sykora, Maxime Talbot, Mike Zigomanis Mario Lemieux CO-OWNER/CHAIRMAN Ray Shero GENERAL MANAGER, Dan Bylsma HEAD COACH © Steve Lansky 2010 bigmouthsports.com NHL and the word mark and image of the Stanley Cup are registered trademarks and the NHL Shield and NHL Conference logos are trademarks of the National Hockey League. All NHL logos and marks and NHL team logos and marks as well as all other proprietary materials depicted herein are the property of the NHL and the respective NHL teams and may not be reproduced without the prior written consent of NHL Enterprises, L.P. Copyright © 2010 National Hockey League. All Rights Reserved. 2009 EASTERN CONFERENCE QUARTER—FINAL 1 BOSTON BRUINS 116 v. 8 MONTRÉAL CANADIENS 93 GM PETER CHIARELLI, HC CLAUDE JULIEN v. GM/HC BOB GAINEY BRUINS SWEEP SERIES Thursday, April 16 1900 h et on CBC Saturday, April 18 2000 h et on CBC MONTREAL 2 @ BOSTON 4 MONTREAL 1 @ BOSTON 5 FIRST PERIOD FIRST PERIOD 1. BOSTON, Phil Kessel 1 (David Krejci, Chuck Kobasew) 13:11 1. BOSTON, Marc Savard 1 (Steve Montador, Phil Kessel) 9:59 PPG 2. BOSTON, David Krejci 1 (Michael Ryder, Milan Lucic) 14:41 2. BOSTON, Chuck Kobasew 1 (Mark Recchi, Patrice Bergeron) 15:12 3. -

2019 CAROLINA HURRICANES DRAFT GUIDE Rogers Arena • Vancouver, B.C

2019 CAROLINA HURRICANES DRAFT GUIDE Rogers Arena • Vancouver, B.C. Round 1: Friday, June 21 – 8 P.M. ET (NBCSN) Hurricanes pick: 28th overall Rounds 2-7: Saturday, June 22 – 1 P.M. ET (NHL Network) Hurricanes picks: Round 2: 36th overall (from BUF), 37th overall (from NYR) and 59th overall; Round 3: 90th overall; Round 4: 121st overall; Round 5: 152nd overall; Round 6: 181st overall (from CGY) and 183rd overall; Round 7: 216th overall (from BOS via NYR) The Carolina Hurricanes hold ten picks in the 2019 NHL Draft, including four in the first two rounds. The first round of the NHL Draft begins on Friday, June 21 at Rogers Arena in Vancouver and will be televised on NBCSN at 8 p.m. ET. Rounds 2-7 will take place on Saturday, June 22 at 1 p.m. ET and will be televised on NHL Network. The Hurricanes made six selections in the 2018 NHL Draft in Dallas, including second-overall pick Andrei Svechnikov. HURRICANES ALL-TIME FIRST HURRICANES DRAFT NOTES ROUND SELECTIONS History of the 28th Pick – Carolina’s first selection in the 2019 NHL Draft will be 28th overall in the first round. Hurricanes captain Justin Williams was taken 28th overall by Year Overall Player Philadelphia in the 2000 NHL Draft, and his 786 career points (312g, 474a) are the most 2018 2 Andrei Svechnikov, RW all-time by a player selected 28th. Other notable active NHL players drafted 28th overall 2017 12 Martin Necas, C include Cory Perry, Nick Foligno, Matt Niskanen, Charlie Coyle, and Brady Skjei. -

Moss Gathers No Tds, Raiders Still Win! Jump to Section by Clicking Image

August 14th, 2006 VOL. 1 ISSUE 1 moss gathers no tds, raiders still win! Jump to section by clicking image PO Box 1316 Alta Loma, CA 91701 (951) 751-1921 [email protected] PUBLISHER & CEO Ron Aguirre CHIEF FINANCIAL OFFICER Bob Polk EXECUTIVE EDITOR IN CHIEF Nick Athan DIR OF STRATEGIC ALIANCES Evan R Press PRODUCTION DESIGN TEAM Bridget Aguirre Arnold Castro Connie Hernandez Andrea Louque Ryan Pasos Gil Rios INFORMATION TECHNOLOGY Josh De Jong MARKETING [email protected] Brian Lemos CUSTOMER SERVICE [email protected] STATISTICAL SERVICES Provided by Stats Inc Associated Press MOSS GATHERS NO TDS, RAIDERS STILL WIN! MINNEAPOLIS (AP) -- Randy Moss wanted so badly to make a 2 - 0 triumphant return to Minnesota. W 16-10 He wanted to put on a show for the fans who supported him so FINAL steadfastly during his seven years here, and greeted him so warm- W 16-13 ly Monday in his first game at the Metrodome since the Vikings OAKLAND 16 traded him to Oakland before last season. MINNESOTA 13 Instead, Moss endured a frustrating night and voiced his displea- sure with both coach Art Shell for the way he benched the receiver and the Vikings organization that shipped him away. QTR SUMMARY Raiders WR Randy Moss, left, is tripped up but not before he gains 16 yards Moss had one catch for 16 yards and Aaron Brooks looked ragged on a second quarter pass from Aaron Brooks, leaving Vikings cornerback 1 2 3 4 again in the Raiders’ 16-13 preseason victory. Dovonte Edwards, right, on the turf Monday. -

Press Clips March 25, 2021

Buffalo Sabres Daily Press Clips March 25, 2021 Sabres’ winless streak hits 15 as Penguins roll to 5-2 win By Will Graves Associated Press March 25, 2021 PITTSBURGH (AP) — The Pittsburgh Penguins are tired. They’re hurting. And in a way, they’re scrambling. Nothing a visit from the reeling Buffalo Sabres can’t fix. Sidney Crosby picked up his 13th goal of the season, Tristan Jarry stopped 26 shots and the Penguins extended Buffalo’s winless streak to 15 games with a 5-2 victory on Wednesday night. Evan Rodrigues, Kris Letang, John Marino and Zach Aston-Reese scored also for the Penguins, who recovered from a sluggish three-game set against New Jersey in which they managed just one victory by pouncing on the undermanned and overmatched Sabres. “We’re a close group, a very resilient group,” Marino said. “We’ve had a lot of come-from-behind wins, a lot of bounce-back wins (like tonight). It says a lot about the guys in the room.” Buffalo goalie Dustin Tokarski, making his first NHL start in more than five years with Carter Hutton out due to a lower-body injury, finished with 37 saves and kept the Sabres in it until late in the second period, when Marino and Aston-Reese scored just over 2 minutes apart to give the Penguins all the cushion required. Rasmus Dahlin scored his second goal of the season and Victor Olofsson beat Jarry on a penalty shot in the third period, but the NHL’s worst team remained in a tailspin. -

2009-2010 Colorado Avalanche Media Guide

Qwest_AVS_MediaGuide.pdf 8/3/09 1:12:35 PM UCQRGQRFCDDGAG?J GEF³NCCB LRCPLCR PMTGBCPMDRFC Colorado MJMP?BMT?J?LAFCÍ Upgrade your speed. CUG@CP³NRGA?QR LRCPLCRDPMKUCQR®. Available only in select areas Choice of connection speeds up to: C M Y For always-on Internet households, wide-load CM Mbps data transfers and multi-HD video downloads. MY CY CMY For HD movies, video chat, content sharing K Mbps and frequent multi-tasking. For real-time movie streaming, Mbps gaming and fast music downloads. For basic Internet browsing, Mbps shopping and e-mail. ���.���.���� qwest.com/avs Qwest Connect: Service not available in all areas. Connection speeds are based on sync rates. Download speeds will be up to 15% lower due to network requirements and may vary for reasons such as customer location, websites accessed, Internet congestion and customer equipment. Fiber-optics exists from the neighborhood terminal to the Internet. Speed tiers of 7 Mbps and lower are provided over fiber optics in selected areas only. Requires compatible modem. Subject to additional restrictions and subscriber agreement. All trademarks are the property of their respective owners. Copyright © 2009 Qwest. All Rights Reserved. TABLE OF CONTENTS Joe Sakic ...........................................................................2-3 FRANCHISE RECORD BOOK Avalanche Directory ............................................................... 4 All-Time Record ..........................................................134-135 GM’s, Coaches ................................................................. -

1988-1989 Panini Hockey Stickers Page 1 of 3 1 Road to the Cup

1988-1989 Panini Hockey Stickers Page 1 of 3 1 Road to the Cup Calgary Flames Edmonton Oilers St. Louis Blues 2 Flames logo 50 Oilers logo 98 Blues logo 3 Flames uniform 51 Oilers uniform 99 Blues uniform 4 Mike Vernon 52 Grant Fuhr 100 Greg Millen 5 Al MacInnis 53 Charlie Huddy 101 Brian Benning 6 Brad McCrimmon 54 Kevin Lowe 102 Gordie Roberts 7 Gary Suter 55 Steve Smith 103 Gino Cavallini 8 Mike Bullard 56 Jeff Beukeboom 104 Bernie Federko 9 Hakan Loob 57 Glenn Anderson 105 Doug Gilmour 10 Lanny McDonald 58 Wayne Gretzky 106 Tony Hrkac 11 Joe Mullen 59 Jari Kurri 107 Brett Hull 12 Joe Nieuwendyk 60 Craig MacTavish 108 Mark Hunter 13 Joel Otto 61 Mark Messier 109 Tony McKegney 14 Jim Peplinski 62 Craig Simpson 110 Rick Meagher 15 Gary Roberts 63 Esa Tikkanen 111 Brian Sutter 16 Flames team photo (left) 64 Oilers team photo (left) 112 Blues team photo (left) 17 Flames team photo (right) 65 Oilers team photo (right) 113 Blues team photo (right) Chicago Blackhawks Los Angeles Kings Toronto Maple Leafs 18 Blackhawks logo 66 Kings logo 114 Maple Leafs logo 19 Blackhawks uniform 67 Kings uniform 115 Maple Leafs uniform 20 Bob Mason 68 Glenn Healy 116 Alan Bester 21 Darren Pang 69 Rolie Melanson 117 Ken Wregget 22 Bob Murray 70 Steve Duchense 118 Al Iafrate 23 Gary Nylund 71 Tom Laidlaw 119 Luke Richardson 24 Doug Wilson 72 Jay Wells 120 Borje Salming 25 Dirk Graham 73 Mike Allison 121 Wendel Clark 26 Steve Larmer 74 Bobby Carpenter 122 Russ Courtnall 27 Troy Murray -

Apba Pro Hockey Roster Sheet 1988-89

APBA PRO HOCKEY ROSTER SHEET 1988-89 BOSTON (BM:0, A/G:1.62, PP:-1, PK:-1) BUFFALO (BM:14, A/G: 1.70, PP:0, PK:0) CALGARY (BM:0, A/G:1.63, PP:+1, PK:-1) Left Wing Center Right Wing Left Wing Center Right Wing Left Wing Center Right Wing BURRIDGE JANNEY NEELY* ANDREYCHUK RUUTTU FOLIGNO ROBERTS, G.R. GILMOUR MULLEN*, J. JOYCE LINSEMAN CARTER ARNIEL TURGEON, P. VAIVE PATTERSON NIEUWENDYK* LOOB CARPENTER SWEENEY, R. CROWDER HARTMAN TUCKER SHEPPARD MacLELLAN OTTO HUNTER, M. BRICKLEY LEHMAN JOHNSTON NAPIER HOGUE PARKER PEPLINSKI FLEURY HUNTER, T. O'DWYER NEUFELD ANDERSSON MAGUIRE HRDINA McDONALD BYERS DONNELLY, M. RANHEIM L. Defense R. Defense Goalies L. Defense R. Defense Goalies L. Defense R. Defense Goalies WESLEY* BOURQUE*, R. MOOG RAMSEY HOUSLEY* MALARCHUK SUTER* MacINNIS VERNON* HAWGOOD GALLEY LEMELIN* KRUPP BODGER PUPPA McCRIMMON MACOUN WAMSLEY SWEENEY, D. THELVÉN ANDERSON, S. LEDYARD CLOUTIER MURZYN RAMAGE CÔTÉ, A.R. QUINTAL PLAYFAIR HALKIDIS WAKALUK NATTRESS GLYNN PEDERSEN, A. SHOEBOTTOM LESSARD SABOURIN CHICAGO (BM:22, A/G:1.59, PP:0, PK:+1) DETROIT (BM:0, A/G:1.65, PP:0, PK:-1) EDMONTON (BM:14, A/G:1.72, PP:-1, PK:-1) Left Wing Center Right Wing Left Wing Center Right Wing Left Wing Center Right Wing GRAHAM SAVARD LARMER GALLANT YZERMAN* MacLEAN, P. TIKKANEN MESSIER* KURRI* THOMAS CREIGHTON PRESLEY BURR OATES BARR SIMPSON CARSON* ANDERSON, G. VINCELETTE MURRAY, T. SUTTER, D. GRAVES KLIMA KOCUR HUNTER, D.P. MacTAVISH LACOMBE BASSEN EAGLES NOONAN KING, K. CHABOT NILL BUCHBERGER McCLELLAND FRYCER SANIPASS HUDSON ROBERTSON MURPHY, J. -

The Media Discourses of Concussions in the National Hockey League By

The Media Discourses of Concussions in the National Hockey League by Jonathan Cabot Thesis submitted to the Faculty of Graduate and Postdoctural Studies in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the Degree of Master of Arts in Human Kinetics School of Human Kinetics Faculty of Health Sciences University of Ottawa ©Jonathan Cabot, Ottawa, Canada, 2017 Abstract The North American ice hockey world has come to realise that concussions are a major problem and a threat to the sport and to the National Hockey League (NHL). The media coverage of the concussions suffered by several NHL stars and of the scientific advancements in the detection and long-term effects of concussions has intensified over the last 20 years. A discourse analysis of Canadian newspaper coverage of concussions in the NHL in 1997-1999 and 2010-2012 focusing on the production of discursive objects and subjects reveals two important discourses. On the one hand, emerging objects of the discourses of blame and responsibility for the concussions in the NHL gained prominence in the later timeframe, especially blame on the NHL, the rulebook and hockey’s violent and risk-taking culture. On the other hand, a shift in reporting saw the emergence of a new subject position for the concussed hockey player, that of a frail and vulnerable subject. More NHL players are covered as ‘suffering’ subjects concerned with both physical pain and the mental health problems associated to concussions, rather than merely as athletes. Indeed, the impact of concussions on the personal lives of players is now an object of discourses that also produce the NHL player as a family member. -

Anaheim Ducks Game Notes

Anaheim Ducks Game Notes Fri, Jan 31, 2020 NHL Game #791 Anaheim Ducks 20 - 25 - 5 (45 pts) Tampa Bay Lightning 30 - 15 - 5 (65 pts) Team Game: 51 12 - 9 - 3 (Home) Team Game: 51 15 - 7 - 2 (Home) Home Game: 25 8 - 16 - 2 (Road) Road Game: 27 15 - 8 - 3 (Road) # Goalie GP W L OT GAA SV% # Goalie GP W L OT GAA SV% 30 Ryan Miller 13 5 5 2 3.01 .904 35 Curtis McElhinney 13 5 6 2 3.10 .902 36 John Gibson 38 15 20 3 2.96 .905 88 Andrei Vasilevskiy 37 25 9 3 2.53 .918 # P Player GP G A P +/- PIM # P Player GP G A P +/- PIM 4 D Cam Fowler 50 9 16 25 1 14 2 D Luke Schenn 15 1 0 1 -9 15 5 D Korbinian Holzer 38 1 3 4 -4 31 9 C Tyler Johnson 45 12 12 24 5 10 6 D Erik Gudbranson 46 4 5 9 2 93 13 C Cedric Paquette 42 4 9 13 -5 24 14 C Adam Henrique 50 17 10 27 -3 16 14 L Pat Maroon 45 6 10 16 1 60 15 C Ryan Getzlaf 48 11 22 33 -11 35 17 L Alex Killorn 48 20 20 40 15 12 20 L Nicolas Deslauriers 38 1 5 6 -6 68 18 L Ondrej Palat 49 12 19 31 20 18 24 C Carter Rowney 50 6 5 11 -2 12 21 C Brayden Point 47 18 26 44 16 9 25 R Ondrej Kase 44 6 14 20 -4 10 22 D Kevin Shattenkirk 50 7 20 27 21 24 29 C Devin Shore 32 2 4 6 -5 8 23 C Carter Verhaeghe 37 6 4 10 -6 6 32 D Jacob Larsson 40 1 3 4 -12 10 27 D Ryan McDonagh 44 1 11 12 2 13 33 R Jakob Silfverberg 45 15 14 29 -3 12 37 C Yanni Gourde 50 6 13 19 -5 32 34 C Sam Steel 45 4 12 16 -9 12 44 D Jan Rutta 30 1 5 6 5 14 37 L Nick Ritchie 29 4 7 11 -2 58 55 D Braydon Coburn 25 1 1 2 6 6 38 C Derek Grant 38 10 5 15 -1 24 67 C Mitchell Stephens 22 2 2 4 -4 4 42 D Josh Manson 31 1 4 5 -4 25 71 C Anthony Cirelli 49 12 -

A Matter of Inches My Last Fight

INDEPENDENT PUBLISHERS GROUP A Matter of Inches How I Survived in the Crease and Beyond Clint Malarchuk, Dan Robson Summary No job in the world of sports is as intimidating, exhilarating, and stressridden as that of a hockey goaltender. Clint Malarchuk did that job while suffering high anxiety, depression, and obsessive compulsive disorder and had his career nearly literally cut short by a skate across his neck, to date the most gruesome injury hockey has ever seen. This autobiography takes readers deep into the troubled mind of Clint Malarchuk, the former NHL goaltender for the Quebec Nordiques, the Washington Capitals, and the Buffalo Sabres. When his carotid artery was slashed during a collision in the crease, Malarchuk nearly died on the ice. Forever changed, he struggled deeply with depression and a dependence on alcohol, which nearly cost him his life and left a bullet in his head. Now working as the goaltender coach for the Calgary Flames, Malarchuk reflects on his past as he looks forward to the future, every day grateful to have cheated deathtwice. 9781629370491 Pub Date: 11/1/14 Author Bio Ship Date: 11/1/14 Clint Malarchuk was a goaltender with the Quebec Nordiques, the Washington Capitals, and the Buffalo Sabres. $25.95 Hardcover Originally from Grande Prairie, Alberta, he now divides his time between Calgary, where he is the goaltender coach for the Calgary Flames, and his ranch in Nevada. Dan Robson is a senior writer at Sportsnet Magazine. He 272 pages lives in Toronto. Carton Qty: 20 Sports & Recreation / Hockey SPO020000 6.000 in W | 9.000 in H 152mm W | 229mm H My Last Fight The True Story of a Hockey Rock Star Darren McCarty, Kevin Allen Summary Looking back on a memorable career, Darren McCarty recounts his time as one of the most visible and beloved members of the Detroit Red Wings as well as his personal struggles with addiction, finances, and women and his daily battles to overcome them.