"#$%&'() + '', %-./0$%)%1 2 ()3 4&(5' 456')5'

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Astronomie in Theorie Und Praxis 8. Auflage in Zwei Bänden Erik Wischnewski

Astronomie in Theorie und Praxis 8. Auflage in zwei Bänden Erik Wischnewski Inhaltsverzeichnis 1 Beobachtungen mit bloßem Auge 37 Motivation 37 Hilfsmittel 38 Drehbare Sternkarte Bücher und Atlanten Kataloge Planetariumssoftware Elektronischer Almanach Sternkarten 39 2 Atmosphäre der Erde 49 Aufbau 49 Atmosphärische Fenster 51 Warum der Himmel blau ist? 52 Extinktion 52 Extinktionsgleichung Photometrie Refraktion 55 Szintillationsrauschen 56 Angaben zur Beobachtung 57 Durchsicht Himmelshelligkeit Luftunruhe Beispiel einer Notiz Taupunkt 59 Solar-terrestrische Beziehungen 60 Klassifizierung der Flares Korrelation zur Fleckenrelativzahl Luftleuchten 62 Polarlichter 63 Nachtleuchtende Wolken 64 Haloerscheinungen 67 Formen Häufigkeit Beobachtung Photographie Grüner Strahl 69 Zodiakallicht 71 Dämmerung 72 Definition Purpurlicht Gegendämmerung Venusgürtel Erdschattenbogen 3 Optische Teleskope 75 Fernrohrtypen 76 Refraktoren Reflektoren Fokus Optische Fehler 82 Farbfehler Kugelgestaltsfehler Bildfeldwölbung Koma Astigmatismus Verzeichnung Bildverzerrungen Helligkeitsinhomogenität Objektive 86 Linsenobjektive Spiegelobjektive Vergütung Optische Qualitätsprüfung RC-Wert RGB-Chromasietest Okulare 97 Zusatzoptiken 100 Barlow-Linse Shapley-Linse Flattener Spezialokulare Spektroskopie Herschel-Prisma Fabry-Pérot-Interferometer Vergrößerung 103 Welche Vergrößerung ist die Beste? Blickfeld 105 Lichtstärke 106 Kontrast Dämmerungszahl Auflösungsvermögen 108 Strehl-Zahl Luftunruhe (Seeing) 112 Tubusseeing Kuppelseeing Gebäudeseeing Montierungen 113 Nachführfehler -

FY08 Technical Papers by GSMTPO Staff

AURA/NOAO ANNUAL REPORT FY 2008 Submitted to the National Science Foundation July 23, 2008 Revised as Complete and Submitted December 23, 2008 NGC 660, ~13 Mpc from the Earth, is a peculiar, polar ring galaxy that resulted from two galaxies colliding. It consists of a nearly edge-on disk and a strongly warped outer disk. Image Credit: T.A. Rector/University of Alaska, Anchorage NATIONAL OPTICAL ASTRONOMY OBSERVATORY NOAO ANNUAL REPORT FY 2008 Submitted to the National Science Foundation December 23, 2008 TABLE OF CONTENTS EXECUTIVE SUMMARY ............................................................................................................................. 1 1 SCIENTIFIC ACTIVITIES AND FINDINGS ..................................................................................... 2 1.1 Cerro Tololo Inter-American Observatory...................................................................................... 2 The Once and Future Supernova η Carinae...................................................................................................... 2 A Stellar Merger and a Missing White Dwarf.................................................................................................. 3 Imaging the COSMOS...................................................................................................................................... 3 The Hubble Constant from a Gravitational Lens.............................................................................................. 4 A New Dwarf Nova in the Period Gap............................................................................................................ -

Star Formation and Galaxy Evolution of the Local Universe Based on HIPASS

Star formation and galaxy evolution of the Local Universe based on HIPASS Oiwei Ivy Wong Submitted in total fulfilment of the requirements of the Degree of Doctor of Philosophy School of Physics University of Melbourne December, 2007 Abstract This thesis investigates the star formation and galaxy evolution of the nearby Local Volume based on Neutral Hydrogen (HI) studies. A large portion of this thesis con- sists of work with the Northern extension of the HI Parkes All Sky Survey (HIPASS). HIPASS is an HI survey of the entire Southern sky up to a declination of +25.5 de- grees (including the Northern extension) using the Parkes 64-metre radio telescope. I have also produced a catalogue of the optical counterparts corresponding to the galaxies found in Northern HIPASS. From this optical catalogue, we also conclude that we did not find any isolated dark galaxies. The other half of my thesis consists of work with the SINGG and SUNGG projects. SINGG is the Survey for Ioniza- tion in Neutral Gas Galaxies and SUNGG is the Survey of Ultraviolet emission in Neutral Gas Galaxies. Both SINGG and SUNGG are selected from HIPASS and are star formation studies in the H-alpha and ultraviolet (UV), respectively. My work in the SINGG-SUNGG collaboration is mostly based on SUNGG. Using the results of SUNGG, I measured the local luminosity density and the cosmic star formation rate density (SFRD) of the Local Universe. Using far-infrared (FIR) observations from IRAS, the FIR luminosity density was also calculated. Combining the FUV luminosity density and the FIR luminosity density, the bolometric SFRD of the Lo- cal Universe was estimated. -

Naming the Extrasolar Planets

Naming the extrasolar planets W. Lyra Max Planck Institute for Astronomy, K¨onigstuhl 17, 69177, Heidelberg, Germany [email protected] Abstract and OGLE-TR-182 b, which does not help educators convey the message that these planets are quite similar to Jupiter. Extrasolar planets are not named and are referred to only In stark contrast, the sentence“planet Apollo is a gas giant by their assigned scientific designation. The reason given like Jupiter” is heavily - yet invisibly - coated with Coper- by the IAU to not name the planets is that it is consid- nicanism. ered impractical as planets are expected to be common. I One reason given by the IAU for not considering naming advance some reasons as to why this logic is flawed, and sug- the extrasolar planets is that it is a task deemed impractical. gest names for the 403 extrasolar planet candidates known One source is quoted as having said “if planets are found to as of Oct 2009. The names follow a scheme of association occur very frequently in the Universe, a system of individual with the constellation that the host star pertains to, and names for planets might well rapidly be found equally im- therefore are mostly drawn from Roman-Greek mythology. practicable as it is for stars, as planet discoveries progress.” Other mythologies may also be used given that a suitable 1. This leads to a second argument. It is indeed impractical association is established. to name all stars. But some stars are named nonetheless. In fact, all other classes of astronomical bodies are named. -

SHOCKS, TURBULENCE, and PARTICLE ACCELERATION

SHOCKS, TURBULENCE, and PARTICLE ACCELERATION MYKOLA GORDOVSKYY University of Manchester STFC Introductory Solar System Plasma Physics Summer School, 12 September 2017 Outline . Basic phenomenology . Shocks - Basic physics (conservation laws etc) - Shocks in the solar corona and collisionless SW plasma - Fermi I particle acceleration . Turbulence - Basic physics in different regimes (collisionless, HD) - Existing misconceptions and non-existent controversies - Turbulence in the corona and SW - Fermi II particle acceleration . Particle acceleration - Mechanisms of particle acceleration - Outstanding problems . Summary and open questions Outline . Basic phenomenology . Shocks - Basic physics (conservation laws etc) - Shocks in the solar corona and collisionless SW plasma - Fermi I particle acceleration . Turbulence - Basic physics in different regimes (collisionless, HD) - Existing misconceptions and non-existent controversies - Turbulence in the corona and SW - Fermi II particle acceleration . Particle acceleration - Mechanisms of particle acceleration - Outstanding problems . Summary and open questions T&Cs, basic phenomenology etc Thermal Non-thermal . Collisional . Collisionless . Particle distribution . No reason for quickly becomes Maxwellian distribution Maxwellian . Behaves like a N-body . Behaves like a fluid system . Magnetohydrodynamics . Kinetics . Fluid lectures: . Kinetic lectures: - Philippa Browning: MHD; - David Tsiklauri: Plasma - Gunnar Hornig: kinetics; Magnetic reconnection; - Eduard Kontar: High- - Valery Nakariakov: -

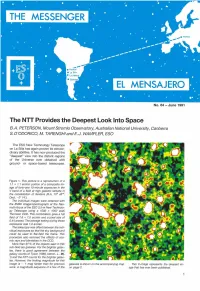

The NTT Provides the Deepest Look Into Space 6

The NTT Provides the Deepest Look Into Space 6. A. PETERSON, Mount Stromlo Observatory,Australian National University, Canberra S. D'ODORICO, M. TARENGHI and E. J. WAMPLER, ESO The ESO New Technology Telescope r on La Silla has again proven its extraor- - dinary abilities. It has now produced the "deepest" view into the distant regions of the Universe ever obtained with ground- or space-based telescopes. Figure 1 : This picture is a reproduction of a I.1 x 1.1 arcmin portion of a composite im- age of forty-one 10-minute exposures in the V band of a field at high galactic latitude in the constellation of Sextans (R.A. loh 45'7 Decl. -0' 143. The individual images were obtained with the EMMI imager/spectrograph at the Nas- myth focus of the ESO 3.5-m New Technolo- gy Telescope using a 1000 x 1000 pixel Thomson CCD. This combination gave a full field of 7.6 x 7.6 arcmin and a pixel size of 0.44 arcsec. The average seeing during these exposures was 1.0 arcsec. The telescope was offset between the indi- vidual exposures so that the sky background could be used to flat-field the frame. This procedure also removed the effects of cos- mic rays and blemishes in the CCD. More than 97% of the objects seen in this sub- field are galaxies. For the brighter galax- ies, there is good agreement between the galaxy counts of Tyson (1988, Astron. J., 96, 1) and the NTT counts for the brighter galax- ies. -

The Rings and Inner Moons of Uranus and Neptune: Recent Advances and Open Questions

Workshop on the Study of the Ice Giant Planets (2014) 2031.pdf THE RINGS AND INNER MOONS OF URANUS AND NEPTUNE: RECENT ADVANCES AND OPEN QUESTIONS. Mark R. Showalter1, 1SETI Institute (189 Bernardo Avenue, Mountain View, CA 94043, mshowal- [email protected]! ). The legacy of the Voyager mission still dominates patterns or “modes” seem to require ongoing perturba- our knowledge of the Uranus and Neptune ring-moon tions. It has long been hypothesized that numerous systems. That legacy includes the first clear images of small, unseen ring-moons are responsible, just as the nine narrow, dense Uranian rings and of the ring- Ophelia and Cordelia “shepherd” ring ε. However, arcs of Neptune. Voyager’s cameras also first revealed none of the missing moons were seen by Voyager, sug- eleven small, inner moons at Uranus and six at Nep- gesting that they must be quite small. Furthermore, the tune. The interplay between these rings and moons absence of moons in most of the gaps of Saturn’s rings, continues to raise fundamental dynamical questions; after a decade-long search by Cassini’s cameras, sug- each moon and each ring contributes a piece of the gests that confinement mechanisms other than shep- story of how these systems formed and evolved. herding might be viable. However, the details of these Nevertheless, Earth-based observations have pro- processes are unknown. vided and continue to provide invaluable new insights The outermost µ ring of Uranus shares its orbit into the behavior of these systems. Our most detailed with the tiny moon Mab. Keck and Hubble images knowledge of the rings’ geometry has come from spanning the visual and near-infrared reveal that this Earth-based stellar occultations; one fortuitous stellar ring is distinctly blue, unlike any other ring in the solar alignment revealed the moon Larissa well before Voy- system except one—Saturn’s E ring. -

Explore Science

SMALL SATELLITE MISSIONS FOR PLANETARY SCIENCE Carolyn R. Mercer, Ph.D. Program Executive, Small Innovative Missions for Planetary Exploration (SIMPLEx) AIAA Small Spacecraft Missions Conference August 4, 2019 Logan, Utah Apollo 15 Particles and Fields Subsatellite (PFS-1) • 35 kg spacecraft flown with Apollo 15 in 1971 • Orbited the Moon for 6 months • Science mission: • Measured the strength and direction of interplanetary and terrestrial magnetic fields • Detected variations in the lunar gravity field • Measured proton and electron flux 2 NASA SCIENCE AN INTEGRATED PROGRAM Helio- Earth physics Science Planetary Astrophysics Science Joint Agency Satellite Division 4 Small Spacecraft for Planetary Science Astrobiology Science and Technology Instrument Development (ASTID) 2008 • O/OREOS (2010 launch) Small Innovative Missions for Planetary Exploration (SIMPLEx-1) 2014 • LunaH-Map, Q-PACE Directed and Partnered Secondary Payloads • MarCO (2018 launch) • LICIA Cube (2021) – potential ASI contribution Planetary Science Deep Space SmallSat Studies (PSDS3) 2017 • 19 Studies – Presented March 2018 at LPSC Small Innovative Missions for Planetary Exploration (SIMPLEx-2) 2018 • Janus, Escapade, Lunar Trailblazer • Next proposals due no earlier than June 2020 5 Planetary Science Deep Space SmallSat Studies Solicitation requested: • Concepts for planetary science missions • 180 kg total spacecraft mass limit • $100M cost cap • No constraints on rides, infrastructure, etc. Solicitation sought answers to: • Can deep space missions be credibly done -

Why Sex? Now Shown That in Water Fleas, Recombination Does Lead to Fewer Deleterious Mutations

PERSPECTIVES EVOLUTION It is assumed that most organisms have sex because the resulting genetic recombination allows Darwinian selection to work better. It is Why Sex? now shown that in water fleas, recombination does lead to fewer deleterious mutations. Rasmus Nielsen hy sex? This has been one of the most sexual reproduction. Additionally, fundamental questions in evolution- the best explanations regarding dele- Wary biology. In many species, males terious mutations rely on strong do not provide parental care to the offspring. assumptions regarding the distribu- Clearly, the rate of reproduction could be tion of selective effects (3), and there increased if all individuals were born as females may be other factors favoring and reproduced asexually without the need to sex, such as increased resistance to mate with a male (parthenogenetic reproduc- pathogens (4). An observed genomic tion). Parthenogenetically reproducing females correlation between the rate of recom- arising in a sexual population should have a bination and variability within species twofold fitness advantage because they, on aver- (5) suggests that there is an interaction age, leave twice as many gene copies in the next between selection and recombination, generation. Nonetheless, sexual reproduction is but a direct difference between sexual ubiquitous in higher organisms. Why do all these and asexual populations has been hard species bother to have males, if males are associ- to establish. ated with a reduction in fitness? The main solu- However, the new study by Paland tion that population geneticists have proposed to and Lynch (1) provides direct empir- this conundrum is that sexual reproduction ical support for an excess accumula- allows genetic recombination, and that genetic tion of mutations in asexually repro- recombination is advantageous because it allows ducing populations compared to natural Darwinian selection to work more effi- sexual populations. -

2016 UK MHD – National Conference on Geophysical, Astrophysical and Industrial Magnetohydrodynamics

2016 UK MHD – National Conference on Geophysical, Astrophysical and Industrial Magnetohydrodynamics Glasgow, 12 and 13 May 2016 Radostin D. Simitev David MacTaggart David R. Fearn — Programme — A long version of this programme including abstracts is available online at http://www.gla.ac.uk/schools/mathematicsstatistics/events/conferences/ukmhd2016. — Thursday, 2016-05-12 — Welcome and Registration 9:00 – 10:25 Arrival, registration, set-up of posters. Refreshments available. 10:25 – 10:30 PROF ADRIAN BOWMAN Head of School Welcome message Invited Lecture Chairperson: Keke Zhang 10:30 – 11:10 PHILIPPA BROWNING Relaxation modelling and MHD simulations of energy release in kink-unstable coronal loops Session 1: Solar Applications I Chairperson: Alan Hood 11:10 – 11:25 TONY ARBER, C. Brady Simulations of Alfven wave driving of the solar chromosphere - efficient heating and spicule launching. 11:25 – 11:40 BEN SNOW, G. Botha, J. McLaughlin, A. Hillier Onset of 2D reconnection in the solar photosphere, chromosphere and corona 11:40 – 11:55 ANDREW HILLIER, Shinsuke Takasao, Naoki Nakamure Investigating slow-mode MHD shocks in a partially ionised plasma 11:55 – 12:10 JAMES THRELFALL, J. E. H. Stevenson, C. E. Parnell, T. Neukirch Particle dynamics at reconnecting magnetic separators 12:10 – 12:25 NIC BIAN, E. Kontar, J. Watters, G. Emslie Turbulent reduction of parallel transport in magnetized plasmas and anomalous cooling of coronal loops Lunch Break 12:25 – 14:00 Lunch is provided at “One A The Square”. The restaurant is located at the North-West corner of the Main University Building. Lunch vouchers enclosed in delegates’ conference wallets. Session 2: Solar Applications II Chairperson: David Hughes 14:00 – 14:15 DAVID PONTIN, G. -

A Basic Requirement for Studying the Heavens Is Determining Where In

Abasic requirement for studying the heavens is determining where in the sky things are. To specify sky positions, astronomers have developed several coordinate systems. Each uses a coordinate grid projected on to the celestial sphere, in analogy to the geographic coordinate system used on the surface of the Earth. The coordinate systems differ only in their choice of the fundamental plane, which divides the sky into two equal hemispheres along a great circle (the fundamental plane of the geographic system is the Earth's equator) . Each coordinate system is named for its choice of fundamental plane. The equatorial coordinate system is probably the most widely used celestial coordinate system. It is also the one most closely related to the geographic coordinate system, because they use the same fun damental plane and the same poles. The projection of the Earth's equator onto the celestial sphere is called the celestial equator. Similarly, projecting the geographic poles on to the celest ial sphere defines the north and south celestial poles. However, there is an important difference between the equatorial and geographic coordinate systems: the geographic system is fixed to the Earth; it rotates as the Earth does . The equatorial system is fixed to the stars, so it appears to rotate across the sky with the stars, but of course it's really the Earth rotating under the fixed sky. The latitudinal (latitude-like) angle of the equatorial system is called declination (Dec for short) . It measures the angle of an object above or below the celestial equator. The longitud inal angle is called the right ascension (RA for short). -

A Review on Substellar Objects Below the Deuterium Burning Mass Limit: Planets, Brown Dwarfs Or What?

geosciences Review A Review on Substellar Objects below the Deuterium Burning Mass Limit: Planets, Brown Dwarfs or What? José A. Caballero Centro de Astrobiología (CSIC-INTA), ESAC, Camino Bajo del Castillo s/n, E-28692 Villanueva de la Cañada, Madrid, Spain; [email protected] Received: 23 August 2018; Accepted: 10 September 2018; Published: 28 September 2018 Abstract: “Free-floating, non-deuterium-burning, substellar objects” are isolated bodies of a few Jupiter masses found in very young open clusters and associations, nearby young moving groups, and in the immediate vicinity of the Sun. They are neither brown dwarfs nor planets. In this paper, their nomenclature, history of discovery, sites of detection, formation mechanisms, and future directions of research are reviewed. Most free-floating, non-deuterium-burning, substellar objects share the same formation mechanism as low-mass stars and brown dwarfs, but there are still a few caveats, such as the value of the opacity mass limit, the minimum mass at which an isolated body can form via turbulent fragmentation from a cloud. The least massive free-floating substellar objects found to date have masses of about 0.004 Msol, but current and future surveys should aim at breaking this record. For that, we may need LSST, Euclid and WFIRST. Keywords: planetary systems; stars: brown dwarfs; stars: low mass; galaxy: solar neighborhood; galaxy: open clusters and associations 1. Introduction I can’t answer why (I’m not a gangstar) But I can tell you how (I’m not a flam star) We were born upside-down (I’m a star’s star) Born the wrong way ’round (I’m not a white star) I’m a blackstar, I’m not a gangstar I’m a blackstar, I’m a blackstar I’m not a pornstar, I’m not a wandering star I’m a blackstar, I’m a blackstar Blackstar, F (2016), David Bowie The tenth star of George van Biesbroeck’s catalogue of high, common, proper motion companions, vB 10, was from the end of the Second World War to the early 1980s, and had an entry on the least massive star known [1–3].