Arxiv:1605.06277V1 [Astro-Ph.IM] 20 May 2016

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Logitech PTZ Pro Camera

THE USB 1080P PTZ CAMERA THAT BRINGS EVERY COLLABORATION TO LIFE Logitech PTZ Pro Camera The Logitech PTZ Pro Camera is a premium USB-enabled HD Set-up is a snap with plug-and-play simplicity and a single USB cable- 1080p PTZ video camera for use in conference rooms, education, to-host connection. Leading business certifications—Certified for health care and other professional video workspaces. Skype for Business, Optimized for Lync, Skype® certified, Cisco Jabber® and WebEx® compatible2—ensure an integrated experience with most The PTZ camera features a wide 90° field of view, 10x lossless full HD business-grade UC applications. zoom, ZEISS optics with autofocus, smooth mechanical 260° pan and 130° tilt, H.264 UVC 1.5 with Scalable Video Coding (SVC), remote control, far-end camera control1 plus multiple presets and camera mounting options for custom installation. Logitech PTZ Pro Camera FEATURES BENEFITS Premium HD PTZ video camera for professional Ideal for conference rooms of all sizes, training environments, large events and other professional video video collaboration applications. HD 1080p video quality at 30 frames per second Delivers brilliantly sharp image resolution, outstanding color reproduction, and exceptional optical accuracy. H.264 UVC 1.5 with Scalable Video Coding (SVC) Advanced camera technology frees up bandwidth by processing video within the PTZ camera, resulting in a smoother video stream in applications like Skype for Business. 90° field of view with mechanical 260° pan and The generously wide field of view and silky-smooth pan and tilt controls enhance collaboration by making it easy 130° tilt to see everyone in the camera’s field of view. -

The Evolution of Keyence Machine Vision Systems

NEW High-Speed, Multi-Camera Machine Vision System CV-X200/X100 Series POWER MEETS SIMPLICITY GLOBAL STANDARD DIGEST VERSION CV-X200/X100 Series Ver.3 THE EVOLUTION OF KEYENCE MACHINE VISION SYSTEMS KEYENCE has been an innovative leader in the machine vision field for more than 30 years. Its high-speed and high-performance machine vision systems have been continuously improved upon allowing for even greater usability and stability when solving today's most difficult applications. In 2008, the XG-7000 Series was released as a “high-performance image processing system that solves every challenge”, followed by the CV-X100 Series as an “image processing system with the ultimate usability” in 2012. And in 2013, an “inline 3D inspection image processing system” was added to our lineup. In this way, KEYENCE has continued to develop next-generation image processing systems based on our accumulated state-of-the-art technologies. KEYENCE is committed to introducing new cutting-edge products that go beyond the expectations of its customers. XV-1000 Series CV-3000 Series THE FIRST IMAGE PROCESSING SENSOR VX Series CV-2000 Series CV-5000 Series CV-500/700 Series CV-100/300 Series FIRST PHASE 1980s to 2002 SECOND PHASE 2003 to 2007 At a time when image processors were Released the CV-300 Series using a color Released the CV-2000 Series compatible with x2 Released the CV-3000 Series that can simultaneously expensive and difficult to handle, KEYENCE camera, followed by the CV-500/700 Series speed digital cameras and added first-in-class accept up to four cameras of eight different types, started development of image processors in compact image processing sensors with 2 mega-pixel CCD cameras to the lineup. -

Visual Homing with a Pan-Tilt Based Stereo Camera Paramesh Nirmal Fordham University

Fordham University Masthead Logo DigitalResearch@Fordham Faculty Publications Robotics and Computer Vision Laboratory 2-2013 Visual homing with a pan-tilt based stereo camera Paramesh Nirmal Fordham University Damian M. Lyons Fordham University Follow this and additional works at: https://fordham.bepress.com/frcv_facultypubs Part of the Robotics Commons Recommended Citation Nirmal, Paramesh and Lyons, Damian M., "Visual homing with a pan-tilt based stereo camera" (2013). Faculty Publications. 15. https://fordham.bepress.com/frcv_facultypubs/15 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Robotics and Computer Vision Laboratory at DigitalResearch@Fordham. It has been accepted for inclusion in Faculty Publications by an authorized administrator of DigitalResearch@Fordham. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Visual homing with a pan-tilt based stereo camera Paramesh Nirmal and Damian M. Lyons Department of Computer Science, Fordham University, Bronx, NY 10458 ABSTRACT Visual homing is a navigation method based on comparing a stored image of the goal location and the current image (current view) to determine how to navigate to the goal location. It is theorized that insects, such as ants and bees, employ visual homing methods to return to their nest [1]. Visual homing has been applied to autonomous robot platforms using two main approaches: holistic and feature-based. Both methods aim at determining distance and direction to the goal location. Navigational algorithms using Scale Invariant Feature Transforms (SIFT) have gained great popularity in the recent years due to the robustness of the feature operator. Churchill and Vardy [2] have developed a visual homing method using scale change information (Homing in Scale Space, HiSS) from SIFT. -

Three Techniques for Rendering Generalized Depth of Field Effects

Three Techniques for Rendering Generalized Depth of Field Effects Todd J. Kosloff∗ Computer Science Division, University of California, Berkeley, CA 94720 Brian A. Barskyy Computer Science Division and School of Optometry, University of California, Berkeley, CA 94720 Abstract Post-process methods are fast, sometimes to the point Depth of field refers to the swath that is imaged in sufficient of real-time [13, 17, 9], but generally do not share the focus through an optics system, such as a camera lens. same image quality as distributed ray tracing. Control over depth of field is an important artistic tool that can be used to emphasize the subject of a photograph. In a A full literature review of depth of field methods real camera, the control over depth of field is limited by the is beyond the scope of this paper, but the interested laws of physics and by physical constraints. Depth of field reader should consult the following surveys: [1, 2, 5]. has been rendered in computer graphics, but usually with the same limited control as found in real camera lenses. In Kosara [8] introduced the notion of semantic depth this paper, we generalize depth of field in computer graphics of field, a somewhat similar notion to generalized depth by allowing the user to specify the distribution of blur of field. Semantic depth of field is non-photorealistic throughout a scene in a more flexible manner. Generalized depth of field provides a novel tool to emphasize an area of depth of field used for visualization purposes. Semantic interest within a 3D scene, to select objects from a crowd, depth of field operates at a per-object granularity, and to render a busy, complex picture more understandable allowing each object to have a different amount of blur. -

TESSERACT -- Antique Scientific Instruments

TESSERACT Early Scientific Instruments Special Issue: OPTICAL PLEASURES Catalogue One Hundred Seven Summer, 2018 $10 CATALOGUE ONE HUNDRED SEVEN Copyright 2018 David Coffeen CONDITIONS OF SALE All items in this catalogue are available at the time of printing. We do not charge for shipping and insurance to anywhere in the contiguous 48 states. New York residents must pay applicable sales taxes. For buyers outside the 48 states, we will provide packing and delivery to the post office or shipper but you must pay the actual shipping charges. Items may be reserved by telephone, and will be held for a reasonable time pending receipt of payment. All items are offered with a 10-day money-back guarantee for any reason, but you pay return postage and insurance. We will do everything possible to expedite your shipment, and can work within the framework of institutional requirements. The prices in this catalogue are net and are in effect through December, 2018. Payments by check, bank transfer, or credit card (Visa, Mastercard, American Express) are all welcome. — David Coffeen, Ph.D. — Yola Coffeen, Ph.D. Members: Scientific Instrument Society American Association for the History of Medicine Historical Medical Equipment Society Antiquarian Horological Society International Society of Antique Scale Collectors Surveyors Historical Society Early American Industries Association The Oughtred Society American Astronomical Society International Coronelli Society American Association of Museums Co-Published : RITTENHOUSE: The Journal of the American Scientific Instrument Enterprise (http://www.etesseract.com/RHjournal/) We are always interested in buying single items or collections. In addition to buying and selling early instruments, we can perform formal appraisals of your single instruments or whole collections, whether to determine fair market value for donation, for insurance, for loss, etc. -

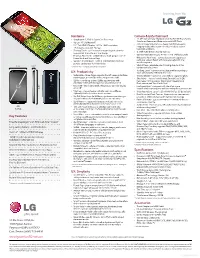

Download Spec Sheet

Hardware Camera & Entertainment • Snapdragon 2.26 GHz Quad-Core Processor • 13 MP Optical Image Stabilization (OIS) Full HD Rear- • T-Mobile 4G LTE Network* Facing Autofocus Camera and Camcorder with LED Flash • 5.2" Full HD IPS Display – 1920 x 1080 resolution, 16:9 • Optical Image Stabilization – clearer results by keeping aspect ratio, and 423 ppi imagery stable while a photo or video is taken, even in • Zerogap Touch – precise touch response by reducing the low-light conditions space under the surface of the display • 2.1 MP Full HD Front-Facing Camera • Rear Key Placement – allows ambidextrous convenience • Camera Resolutions: up to 4160 x 31201 for the most natural and immediate use (4160 x 2340 default) pixels • Sapphire Crystal Glass – scratch-resistant material helps • Multipoint Autofocus – camera detects and captures a protect camera lens from blemishes particular subject faster and more precisely with nine autofocus points * T-Mobile’s 4G LTE Network not available everywhere. • Shot & Clear – eliminate select moving objects in the 2.79" 0.35" background of a picture UX Productivity • Tracking Zoom1 – zoom in on a subject while recording to • Slide Aside – three-finger swipe to the left saves up to track and magnify it through the scene three running apps; access tabs with a swipe to the right • Voice Shutter – take pictures using voice commands • QSlide – overlay up to two QSlide app windows with • Shot Mode – choose from Normal, Shot & Clear,1 Dynamic Tone adjustable sizing and transparency on primary screen (HDR),1 Panorama,1 -

FOCUSING the VIEW CAMERA Iii

)2&86,1* WKH 9,(:&$0(5$ $6FLHQWLILF:D\ WRIRFXV WKH9LHZ&DPHUD DQG (VWLPDWH'HSWKRI)LHOG J E\+DUROG00HUNOLQJHU )2&86,1* WKH 9,(:&$0(5$ $6FLHQWLILF:D\ WRIRFXV WKH9LHZ&DPHUD DQG (VWLPDWH'HSWKRI)LHOG E\ +DUROG00HUNOLQJHU 3XEOLVKHGE\WKHDXWKRU 7KLVYHUVLRQH[LVWVLQ HOHFWURQLF 3') IRUPDWRQO\ ii Published by the author: Harold M. Merklinger P. O. Box 494 Dartmouth, Nova Scotia Canada, B2Y 3Y8 v.1.0 1 March 1993 2nd Printing 29 March 1996 3rd Printing 27 August 1998 1st Internet Edition v. 1.6 29 Dec 2006 Corrected for iPad v. 1.6.1 30 July 2010 ISBN 0-9695025-2-4 © All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reproduced or translated without the express written permission of the author. ‘Printed’ in electronic format by the author, using Adobe Acrobat. Dedicated to view camera users everywhere. FOCUSING THE VIEW CAMERA iii &217(176 3DJH 3UHIDFH LY &+$37(5 ,QWURGXFWLRQ &+$37(5 *HWWLQJ6WDUWHG &+$37(5 'HILQLWLRQV 7KH/HQV 7KH)LOPDQGWKH,PDJH6SDFH 7KH3ODQHRI6KDUS)RFXVDQGWKH2EMHFW6SDFH 2WKHU7HUPVDQG'LVWDQFHV &+$37(5 9LHZ&DPHUD2SWLFDO3ULQFLSOHV 7LOWDQG6ZLQJ 'LVFXVVLRQ &+$37(5 3HUVSHFWLYHDQG'LVWRUWLRQ &+$37(5 'HSWKRI)LHOG ,PDJH%DVHG'HSWKRI)LHOG 2EMHFW%DVHG'HSWKRI)LHOG 'LVFXVVLRQ &+$37(5 $6LPSOHU0HWKRG &+$37(5 $Q([DPSOH &+$37(5 7XWRULDO &RQVLGHUDWLRQV $6ROXWLRQ $GGLWLRQDO&RPPHQWV 2WKHU:D\V &+$37(5 6XPPDU\ 0DLQ0HVVDJH 7DEOHRI+\SHUIRFDO'LVWDQFHV %LEOLRJUDSK\ &+$37(5 7DEOHV ,QGH[WR7DEOHV (IIHFWLYHIRFDOOHQJWK iv Merklinger: FOCUSING THE VIEW CAMERA &+$37(5 7DEOHV FRQWLQXHG +LQJHOLQHWLOW (IIHFWLYHWLOWIRUERWKVZLQJDQGWLOW /HQVWLOWDQJOHIRUJLYHQIRFDOOHQJWKfDQGGLVWDQFHJ -

HD-310U High Definition Camera UNMATCHED QUALITY AND

A Carter Family Update HD-310U High Definition Camera SCIENTIFIC. MEDICAL. INDUSTRIAL UNMATCHED QUALITY AND SIMPLICITY The NEW HD-310U video camera is a game-changer for live imaging applications. This is a unique camera to the industry, providing simultaneous outputs via HDMI and USB 3.0. The HDMI output connects directly to an HD display for live viewing (no PC required); while the new USB 3.0 output allows real-time live viewing and image capture on a PC – both at fast 60 fps! The HD-310U utilizes the latest color CMOS sensor to provide increased sensitivity to display impeccably clear images for both brightfield and bright fluorescence applications. The simplistic MagicApp software offers digital camera adjustments and enables users to snap images with the click of a mouse. • HDMI 1080p output at 60fps for live viewing (no PC required) • USB 3.0 1080p output at 60fps for PC connection • USB & HDMI outputs can be viewed simultaneously • Factory programmed to display best possble image • Exceptional color reproduction - 12-color channel matrix • Automatically adjusts to changes in light sensitivity • MagicApp software included for live image capture • Plug-and-play camera that DOES NOT require training Pathology Microscopy Tumor Board Review Classroom Demonstrations Semiconductor Inspection Brightfield Live Cell Imaging Metrology Scientific Imaging www.dagemti.com - 701 N. Roeske Ave, Michigan City, IN 46360 - P: (219) 872-5514 UNMATCHED QUALITY AND SIMPLICITY USB 3.0 Dimensions HDMI HD-310U CAMERA - SPECIFICATIONS Image Sensor: 1/2.8 inch color CMOS (progressive scan) Output Pixels: Horizontal: 1920, Vertical: 1080 Output Signal: HDMI Type A Terminal USB Video Class 1.1 Micro-B connector (in conformity with USB 3.1 Gen 1) 1920 x 1080 – 60fps (USB 3.0) 1920 x 1080 – 12fps (USB 2.0) Sensitivity: F10 standard (2000lx, 3100k, gain OFF, gamma OFF, 59,94Hz) Power: DC 12V +/- 10%, power consumption approx. -

Texas 4-H Photography Project Explore Photography

Texas 4-H Photography Project Explore Photography texas4-h.tamu.edu The members of Texas A&M AgriLife will provide equal opportunities in programs and activities, education, and employment to all persons regardless of race, color, sex, religion, national origin, age, disability, genetic information, veteran status, sexual orientation or gender identity and will strive to achieve full and equal employment opportunity throughout Texas A&M AgriLife. TEXAS 4-H PHOTOGRAPHY PROJECT Description With a network of more than 6 million youth, 600,000 volunteers, 3,500 The Texas 4-H Explore professionals, and more than 25 million alumni, 4-H helps shape youth series allows 4-H volunteers, to move our country and the world forward in ways that no other youth educators, members, and organization can. youth who may be interested in learning more about 4-H Texas 4-H to try some fun and hands- Texas 4-H is like a club for kids and teens ages 5-18, and it’s BIG! It’s on learning experiences in a the largest youth development program in Texas with more than 550,000 particular project or activity youth involved each year. No matter where you live or what you like to do, area. Each guide features Texas 4-H has something that lets you be a better you! information about important aspects of the 4-H program, You may think 4-H is only for your friends with animals, but it’s so much and its goal of teaching young more! You can do activities like shooting sports, food science, healthy people life skills through hands- living, robotics, fashion, and photography. -

Key Features 5.2" Hardware UX: Productivity UX: Simplicity

Hardware Camera & Entertainment • Snapdragon 2.26 GHz Quad-Core Processor • 13 MP Optical Image Stabilization (OIS) Full HD Rear-Facing • Verizon 4G LTE Network* Autofocus Camera and Camcorder with LED Flash • 5.2" Full HD IPS Display: 1920 x 1080 resolution, • Optical Image Stabilization – clearer results by keeping 16:9 aspect ratio, and 423 ppi imagery stable while a photo or video is taken, even in low-light conditions • Zerogap Touch – precise touch response by reducing the • 2.1 MP Full HD Front-Facing Camera space under the surface of the display 1 • Rear Key Placement – ambidextrous, multi-purpose use of • Camera Resolutions: up to 4160 x 2340 (default) pixels Power/Lock and Volume Keys • Multipoint Autofocus – camera detects and captures a • Sapphire Crystal Glass – scratch-resistant material helps particular subject faster and more precisely with nine protect camera lens from blemishes autofocus points 2.79" 0.36" • Shot & Clear – eliminate select moving objects in the * Verizon’s 4G LTE Network not available everywhere. background of a picture • Tracking Zoom1 – zoom in on a subject while recording to UX: Productivity track and magnify it through the scene • Slide Aside – three-finger swipe to the left saves up to three • Cheese Shutter – use voice commands to capture a photo running apps; access tabs with a swipe to the right • Shot Mode – choose from Normal, Shot & Clear,1 HDR,1 • QSlide – overlay up to two QSlide app windows with Panorama,1 VR Panorama,1 Burst Shot,1 Beauty Shot, adjustable sizing and transparency on primary -

Plug-And-Play Simplicity with Superb Image Quality Sony's SRG-120DU USB 3.0 PTZ Camera Is Ideal for Visual Communications and Remote Monitoring Applications

Plug-and-play simplicity with superb image quality Sony's SRG-120DU USB 3.0 PTZ camera is ideal for visual communications and remote monitoring applications. The SRG-120DU USB 3.0 UVC video compatible PTZ camera is the newest member to join Sony’s SRG PTZ high-definition remotely operated camera line-up. This affordable professional 1080p/60 Full HD USB 3.0 PTZ camera is designed to interface easily with a dedicated computer system using the same USB technology found on most computers. Simply connect the camera directly to any standard PC through its USB 3.0 input and you are quickly connected with popular Unified Communications and Collaboration (UCC) and multimedia streaming devices. With a high-sensitivity 1/2.8-type Exmor® CMOS sensor as well as View-DR® technology, the camera provides extremely wide dynamic range with Sony’s full-capture Wide-D technology to compensate for backlight or changing lighting conditions. In addition, its XDNR® technology reduces noise and provides clear images in low lighting conditions. The camera's extremely wide field of view (71°) and 12x optical/12x digital zoom auto focus lens make it ideal for small- to mid-sized rooms. The camera features fast and silent pan/tilt/zoom capabilities and is controllable via VISCA protocol (RS-232 and RJ45 [IP] connectors). The drive motor noise is less than 35dB, making it perfect for noise-restricted environments like hospitals, classrooms, and meeting rooms. Available in a silver housing, its all-in-one compact and lightweight design makes it easy to install in a variety of locations. -

Detecting Rule of Simplicity from Photos

Detecting Rule of Simplicity from Photos Long Mai, Hoang Le, Yu-Chi Lai Feng Liu Yuzhen Niu National Taiwan University of Portland State University Portland State University Science and Technology Portland, OR 97207-0751 Portland, OR 97207-0751 #43, Sec. 4, Keelung Rd., fl[email protected] {mtlong, hoanl, Taipei 106, Taiwan yuzhen}@cs.pdx.edu [email protected] ABSTRACT Simplicity refers to one of the most important photography composition rules. Simplicity states that simplifying the im- age background can draw viewers’ attention to the subject of interest in a photograph and help them better compre- hend and appreciate it. Understanding whether a photo respects photography rules or not facilitates photo quality assessment. In this paper, we present a method to automat- ically detect whether a photo is composed according to the (a) Homogenous or empty background rule of simplicity. We design features according to the defi- nition, implementation and effect of the rule. First, we make use of saliency analysis to infer the subject of interest in a photo and measure its compactness. Second, we segment an image into background and foreground and measure the ho- mogeneity within the background as another feature. Third, when looking at an image created with the rule of simplic- ity, different viewers tend to agree on what the subject of interest is in this photo. We accordingly measure the consis- (b) Out-of-focus background (c) Cluttered background tency among various saliency detection results as a feature. Figure 1: Rule of simplicity. Simplifying the back- We experiment with these features in a range of machine ground in an image by making it homogenous, learning methods.