A Pathway of Targeted Autophagy Is Induced by DNA Damage in Budding Yeast

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

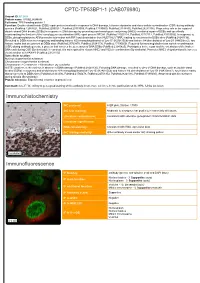

CPTC-TP53BP1-1 (CAB079980) Immunohistochemistry Immunofluorescence

CPTC-TP53BP1-1 (CAB079980) Uniprot ID: Q12888 Protein name: TP53B_HUMAN Full name: TP53-binding protein 1 Function: Double-strand break (DSB) repair protein involved in response to DNA damage, telomere dynamics and class-switch recombination (CSR) during antibody genesis (PubMed:12364621, PubMed:22553214, PubMed:23333306, PubMed:17190600, PubMed:21144835, PubMed:28241136). Plays a key role in the repair of double-strand DNA breaks (DSBs) in response to DNA damage by promoting non-homologous end joining (NHEJ)- mediated repair of DSBs and specifically counteracting the function of the homologous recombination (HR) repair protein BRCA1 (PubMed:22553214, PubMed:23727112, PubMed:23333306). In response to DSBs, phosphorylation by ATM promotes interaction with RIF1 and dissociation from NUDT16L1/TIRR, leading to recruitment to DSBs sites (PubMed:28241136). Recruited to DSBs sites by recognizing and binding histone H2A monoubiquitinated at 'Lys-15' (H2AK15Ub) and histone H4 dimethylated at 'Lys-20' (H4K20me2), two histone marks that are present at DSBs sites (PubMed:23760478, PubMed:28241136, PubMed:17190600). Required for immunoglobulin class-switch recombination (CSR) during antibody genesis, a process that involves the generation of DNA DSBs (PubMed:23345425). Participates in the repair and the orientation of the broken DNA ends during CSR (By similarity). In contrast, it is not required for classic NHEJ and V(D)J recombination (By similarity). Promotes NHEJ of dysfunctional telomeres via interaction with PAXIP1 (PubMed:23727112). Subcellular -

RIDDLE Immunodeficiency Syndrome Is Linked to Defects in 53BP1-Mediated DNA Damage Signaling

RIDDLE immunodeficiency syndrome is linked to defects in 53BP1-mediated DNA damage signaling Grant S. Stewart*†, Tatjana Stankovic*, Philip J. Byrd*, Thomas Wechsler‡, Edward S. Miller*, Aarn Huissoon§, Mark T. Drayson¶, Stephen C. West‡, Stephen J. Elledge†ʈ, and A. Malcolm R. Taylor* *Cancer Research UK, Institute for Cancer Studies, Birmingham University, Vincent Drive, Edgbaston, Birmingham B15 2TT, United Kingdom; ‡Cancer Research UK, Clare Hall Laboratories, London Research Institute, South Mimms, Hertfordshire EN6 3LD, United Kingdom; §Department of Immunology, Birmingham Heartlands Hospital, Birmingham, B9 5SS, United Kingdom; ¶Division of Immunity and Infection, Birmingham University Medical School, Vincent Drive, Edgbaston, Birmingham B15 2TT, United Kingdom; and ʈHoward Hughes Medical Institute, Department of Genetics, Harvard Partners Center for Genetics and Genomics, Harvard Medical School, 77 Avenue Louis Pasteur, Boston, MA 02115 Contributed by Stephen J. Elledge, September 6, 2007 (sent for review July 6, 2007) Cellular DNA double-strand break-repair pathways have evolved with an alternative constant region (e.g., ␣, ␥, ) to generate to protect the integrity of the genome from a continual barrage of different Ig isotypes e.g., IgA, IgG, and IgE (2). potentially detrimental insults. Inherited mutations in genes that During the process of CSR, it has been hypothesized that two control this process result in an inability to properly repair DNA closely positioned single-stranded DNA nicks result in the damage, ultimately -

WO 2019/079361 Al 25 April 2019 (25.04.2019) W 1P O PCT

(12) INTERNATIONAL APPLICATION PUBLISHED UNDER THE PATENT COOPERATION TREATY (PCT) (19) World Intellectual Property Organization I International Bureau (10) International Publication Number (43) International Publication Date WO 2019/079361 Al 25 April 2019 (25.04.2019) W 1P O PCT (51) International Patent Classification: CA, CH, CL, CN, CO, CR, CU, CZ, DE, DJ, DK, DM, DO, C12Q 1/68 (2018.01) A61P 31/18 (2006.01) DZ, EC, EE, EG, ES, FI, GB, GD, GE, GH, GM, GT, HN, C12Q 1/70 (2006.01) HR, HU, ID, IL, IN, IR, IS, JO, JP, KE, KG, KH, KN, KP, KR, KW, KZ, LA, LC, LK, LR, LS, LU, LY, MA, MD, ME, (21) International Application Number: MG, MK, MN, MW, MX, MY, MZ, NA, NG, NI, NO, NZ, PCT/US2018/056167 OM, PA, PE, PG, PH, PL, PT, QA, RO, RS, RU, RW, SA, (22) International Filing Date: SC, SD, SE, SG, SK, SL, SM, ST, SV, SY, TH, TJ, TM, TN, 16 October 2018 (16. 10.2018) TR, TT, TZ, UA, UG, US, UZ, VC, VN, ZA, ZM, ZW. (25) Filing Language: English (84) Designated States (unless otherwise indicated, for every kind of regional protection available): ARIPO (BW, GH, (26) Publication Language: English GM, KE, LR, LS, MW, MZ, NA, RW, SD, SL, ST, SZ, TZ, (30) Priority Data: UG, ZM, ZW), Eurasian (AM, AZ, BY, KG, KZ, RU, TJ, 62/573,025 16 October 2017 (16. 10.2017) US TM), European (AL, AT, BE, BG, CH, CY, CZ, DE, DK, EE, ES, FI, FR, GB, GR, HR, HU, ΓΕ , IS, IT, LT, LU, LV, (71) Applicant: MASSACHUSETTS INSTITUTE OF MC, MK, MT, NL, NO, PL, PT, RO, RS, SE, SI, SK, SM, TECHNOLOGY [US/US]; 77 Massachusetts Avenue, TR), OAPI (BF, BJ, CF, CG, CI, CM, GA, GN, GQ, GW, Cambridge, Massachusetts 02139 (US). -

Role of Cyclin-Dependent Kinase 1 in Translational Regulation in the M-Phase

cells Review Role of Cyclin-Dependent Kinase 1 in Translational Regulation in the M-Phase Jaroslav Kalous *, Denisa Jansová and Andrej Šušor Institute of Animal Physiology and Genetics, Academy of Sciences of the Czech Republic, Rumburska 89, 27721 Libechov, Czech Republic; [email protected] (D.J.); [email protected] (A.Š.) * Correspondence: [email protected] Received: 28 April 2020; Accepted: 24 June 2020; Published: 27 June 2020 Abstract: Cyclin dependent kinase 1 (CDK1) has been primarily identified as a key cell cycle regulator in both mitosis and meiosis. Recently, an extramitotic function of CDK1 emerged when evidence was found that CDK1 is involved in many cellular events that are essential for cell proliferation and survival. In this review we summarize the involvement of CDK1 in the initiation and elongation steps of protein synthesis in the cell. During its activation, CDK1 influences the initiation of protein synthesis, promotes the activity of specific translational initiation factors and affects the functioning of a subset of elongation factors. Our review provides insights into gene expression regulation during the transcriptionally silent M-phase and describes quantitative and qualitative translational changes based on the extramitotic role of the cell cycle master regulator CDK1 to optimize temporal synthesis of proteins to sustain the division-related processes: mitosis and cytokinesis. Keywords: CDK1; 4E-BP1; mTOR; mRNA; translation; M-phase 1. Introduction 1.1. Cyclin Dependent Kinase 1 (CDK1) Is a Subunit of the M Phase-Promoting Factor (MPF) CDK1, a serine/threonine kinase, is a catalytic subunit of the M phase-promoting factor (MPF) complex which is essential for cell cycle control during the G1-S and G2-M phase transitions of eukaryotic cells. -

PRODUCT INFORMATION TP53BP1 BRCT Domains (Human Recombinant) Item No

PRODUCT INFORMATION TP53BP1 BRCT domains (human recombinant) Item No. 14171 • Batch No. XXXX Overview and Properties Synonyms: Tumor Protein p53 binding Protein 1, Tumor Suppressor p53-binding Protein 1 Source: Recombinant human N-terminal GST-tagged protein expressed in E. coli amino acids 1,717-1,972 (N- and C-terminal truncation) Uniprot No.: Q12888 Batch specific information can be found on the Batch Specific Insert or by contacting Technical Support Molecular Weight: 55.1 kDa Storage: -80°C (as supplied) Stability: ≥6 months Purity: batch specific Supplied in: 50 mM Tris-HCl, pH 8.0, containing 150 mM sodium chloride and 20% glycerol Protein Concentration: batch specific mg/ml Image(s) 1 2 3 4 250 kDa · · · · · · · 150 kDa · · · · · · · 100 kDa · · · · · · · 75 kDa · · · · · · · 50 kDa · · · · · · · 37 kDa · · · · · · · 25 kDa · · · · · · · 20 kDa · · · · · · · Lane 1: MW Markers Lane 2: TP53BP1 BRCT domains (1 µg) Lane 3: TP53BP1 BRCT domains (2 µg) Lane 4: TP53BP1 BRCT domains (5 µg) Representative gel image shown; actual purity may vary between each batch. WARNING CAYMAN CHEMICAL THIS PRODUCT IS FOR RESEARCH ONLY - NOT FOR HUMAN OR VETERINARY DIAGNOSTIC OR THERAPEUTIC USE. 1180 EAST ELLSWORTH RD SAFETY DATA ANN ARBOR, MI 48108 · USA This material should be considered hazardous until further information becomes available. Do not ingest, inhale, get in eyes, on skin, or on clothing. Wash thoroughly after handling. Before use, the user must review the complete Safety Data Sheet, which has been sent via email to your institution. PHONE: [800] 364-9897 WARRANTY AND LIMITATION OF REMEDY [734] 971-3335 Buyer agrees to purchase the material subject to Cayman’s Terms and Conditions. -

Ubch7 Regulates 53BP1 Stability and DSB Repair

UbcH7 regulates 53BP1 stability and DSB repair Xiangzi Hana,1, Lei Zhanga,1, Jinsil Chunga,1, Franklin Mayca Pozoa, Amanda Trana, Darcie D. Seachrista, James W. Jacobbergerb, Ruth A. Keria, Hannah Gilmorec, and Youwei Zhanga,2 aDepartment of Pharmacology, bDivision of General Medical Sciences, Case Comprehensive Cancer Center, School of Medicine, and cUniversity Hospitals Case Medical Center, Case Western Reserve University, Cleveland, OH 44106 Edited by Tony Hunter, The Salk Institute for Biological Studies, La Jolla, CA, and approved November 3, 2014 (received for review May 8, 2014) DNA double-strand break (DSB) repair is not only key to genome and generation of one-ended DSBs. Such one-ended DSBs re- stability but is also an important anticancer target. Through an quire HR, but not NHEJ, to repair (8). In contrast, repair of one- shRNA library-based screening, we identified ubiquitin-conjugat- ended DSBs by NHEJ leads to radial chromosomes and cell death ing enzyme H7 (UbcH7, also known as Ube2L3), a ubiquitin E2 (12–14). Therefore, stabilization of 53BP1 by UbcH7 depletion enzyme, as a critical player in DSB repair. UbcH7 regulates both increased the sensitivity of cancers cells to CPT and other DNA the steady-state and replicative stress-induced ubiquitination damaging agents. Our data suggest a novel strategy in enhancing and proteasome-dependent degradation of the tumor suppressor the anticancer effect of radiotherapy or chemotherapy through p53-binding protein 1 (53BP1). Phosphorylation of 53BP1 at the N terminus is involved in the replicative stress-induced 53BP1 degra- stabilizing or increasing 53BP1. dation. Depletion of UbcH7 stabilizes 53BP1, leading to inhibition Results of DSB end resection. -

Tumor Suppressor and DNA Damage Response Panel 2

Tumor suppressor and DNA damage response panel 2 (55 analytes) Gene Symbol Target protein name UniProt ID (& link) Modification* *blanks mean the assay detects the ACT Actin; ACTA2 ACTA1 ACTB ACTG1 ACTC1 ACTG2 Q562L2 non‐modified peptide sequence CASC5 cancer susceptibility candidate 5 Q8NG31 pS767 CASC5 cancer susceptibility candidate 5 Q8NG31 CASP3 caspase 3, apoptosis‐related cysteine peptidase P42574 pS26 CDC25B cell division cycle 25 homolog B (S. pombe) P30305 pS16 CDC25B cell division cycle 25 homolog B (S. pombe) P30305 pS323 CDC25B cell division cycle 25 homolog B (S. pombe) P30305 CDC25C cell division cycle 25 homolog B (S. pombe) P30307 pS216 CDC25C cell division cycle 25 homolog B (S. pombe) P30307 CDCA8 cell division cycle associated 8 Q53HL2 pT16 CDK1 cyclin‐dependent kinase 1 P06493 pT161 CDK1 cyclin‐dependent kinase 1 P06493 CDK7 cyclin‐dependent kinase 7 P50613 pT17 CHEK1 CHK1 checkpoint homolog (S. pombe) O14757 pS286 CHEK2 CHK2 checkpoint homolog (S. pombe) O96017 pS379 CHEK2 CHK2 checkpoint homolog (S. pombe) O96017 pT387 CHEK2 CHK2 checkpoint homolog (S. pombe) O96017 GAPDH Glyceraldehyde‐3‐phosphate dehydrogenase P04406 LAT linker for activation of T cells O43561 pS224 LMNB1 lamin B1 P20700 pT2; pS23 LMNB1 lamin B1 P20700 pT2 LMNB1 lamin B1 P20700 pS23 MCM6 minichromosome maintenance complex component 6 Q14566 pS762 MCM6 minichromosome maintenance complex component 6 Q14566 MDM2 Mdm2, transformed 3T3 cell double minute 2, p53 binding protein (mouse) Q00987 pS166 MDM2 Mdm2, transformed 3T3 cell double minute 2, p53 binding protein (mouse) Q00987 MKI67 antigen identified by monoclonal antibody Ki‐67 P46013 pT181 MKI67 antigen identified by monoclonal antibody Ki‐67 P46013 MKI67 antigen identified by monoclonal antibody Ki‐67 P46013 pT246 MRE11A MRE11 meiotic recombination 11 homolog A (S. -

Analysis of 3-Phosphoinositide-Dependent Kinase-1 Signaling and Function in ES Cells

EXPERIMENTAL CELL RESEARCH 314 (2008) 2299– 2312 available at www.sciencedirect.com www.elsevier.com/locate/yexcr Research Article Analysis of 3-phosphoinositide-dependent kinase-1 signaling and function in ES cells Tanja Tamgüneya,b, Chao Zhangc, Dorothea Fiedlerc, Kevan Shokatc, David Stokoea,⁎ aUCSF Cancer Research Institute, USA bMolecular Medicine Program, Friedrich-Alexander University of Erlangen-Nuremberg, Erlangen, Germany cDepartment of Cellular and Molecular Pharmacology, University of California, San Francisco, 2340 Sutter Street, San Francisco, CA 94115, USA ARTICLE INFORMATION ABSTRACT Article Chronology: 3-Phosphoinositide-dependent kinase-1 (PDK1) phosphorylates and activates several Received 5 February 2008 kinases in the cAMP-dependent, cGMP-dependent and protein kinase C (AGC) family. Revised version received Many putative PDK1 substrates have been identified, but have not been analyzed following 15 April 2008 transient and specific inhibition of PDK1 activity. Here, we demonstrate that a previously Accepted 16 April 2008 characterized PDK1 inhibitor, BX-795, shows biological effects that are not consistent with Available online 23 April 2008 PDK1 inhibition. Therefore, we describe the creation and characterization of a PDK1 mutant, L159G, which can bind inhibitor analogues containing bulky groups that hinder access to the − − Keywords: ATP binding pocket of wild type (WT) kinases. When expressed in PDK1 / ES cells, PDK1 PDK1 L159G restored phosphorylation of PDK1 targets known to be hypophosphorylated in these PKB/Akt cells. Screening of multiple inhibitor analogues showed that 1-NM-PP1 and 3,4-DMB-PP1 − − PI3K optimally inhibited the phosphorylation of PDK1 targets in PDK1 / ES cells expressing PDK1 Chemical genetics L159G but not WT PDK1. These compounds confirmed previously assumed PDK1 substrates, AGC kinases but revealed distinct dephosphorylation kinetics. -

Targeted Mass Spectrometry Enables Quantification of Novel

cancers Article Targeted Mass Spectrometry Enables Quantification of Novel Pharmacodynamic Biomarkers of ATM Kinase Inhibition Jeffrey R. Whiteaker 1 , Tao Wang 1, Lei Zhao 1, Regine M. Schoenherr 1, Jacob J. Kennedy 1, Ulianna Voytovich 1, Richard G. Ivey 1, Dongqing Huang 1, Chenwei Lin 1, Simona Colantonio 2, Tessa W. Caceres 2, Rhonda R. Roberts 2, Joseph G. Knotts 2, Jan A. Kaczmarczyk 2, Josip Blonder 2, Joshua J. Reading 2, Christopher W. Richardson 2, Stephen M. Hewitt 3, Sandra S. Garcia-Buntley 2, William Bocik 2, Tara Hiltke 4, Henry Rodriguez 4, Elizabeth A. Harrington 5, J. Carl Barrett 5, Benedetta Lombardi 5, Paola Marco-Casanova 5, Andrew J. Pierce 5 and Amanda G. Paulovich 1,* 1 Fred Hutchinson Cancer Research Center, Clinical Research Division, Seattle, WA 98109, USA; [email protected] (J.R.W.); [email protected] (T.W.); [email protected] (L.Z.); [email protected] (R.M.S.); [email protected] (J.J.K.); [email protected] (U.V.); [email protected] (R.G.I.); [email protected] (D.H.); [email protected] (C.L.) 2 Cancer Research Technology Program, Antibody Characterization Lab, Frederick National Laboratory for Cancer Research, Frederick, MD 21701, USA; [email protected] (S.C.); [email protected] (T.W.C.); [email protected] (R.R.R.); [email protected] (J.G.K.); [email protected] (J.A.K.); [email protected] (J.B.); [email protected] (J.J.R.); [email protected] (C.W.R.); [email protected] (S.S.G.-B.); [email protected] (W.B.) 3 Experimental Pathology Laboratory, Laboratory of Pathology, Center for Cancer Research, National Cancer Citation: Whiteaker, J.R.; Wang, T.; Institute, National Institute of Health, Bethesda, MD 20892, USA; [email protected] Zhao, L.; Schoenherr, R.M.; Kennedy, 4 Office of Cancer Clinical Proteomics Research, National Cancer Institute, Bethesda, MD 20892, USA; J.J.; Voytovich, U.; Ivey, R.G.; Huang, [email protected] (T.H.); [email protected] (H.R.) D.; Lin, C.; Colantonio, S.; et al. -

Dynamic Modelling of the Mtor Signalling Network Reveals Complex

www.nature.com/scientificreports OPEN Dynamic modelling of the mTOR signalling network reveals complex emergent behaviours conferred by Received: 24 August 2017 Accepted: 1 December 2017 DEPTOR Published: xx xx xxxx Thawfeek M. Varusai1,4 & Lan K. Nguyen2,3,4 The mechanistic Target of Rapamycin (mTOR) signalling network is an evolutionarily conserved network that controls key cellular processes, including cell growth and metabolism. Consisting of the major kinase complexes mTOR Complex 1 and 2 (mTORC1/2), the mTOR network harbours complex interactions and feedback loops. The DEP domain-containing mTOR-interacting protein (DEPTOR) was recently identifed as an endogenous inhibitor of both mTORC1 and 2 through direct interactions, and is in turn degraded by mTORC1/2, adding an extra layer of complexity to the mTOR network. Yet, the dynamic properties of the DEPTOR-mTOR network and the roles of DEPTOR in coordinating mTORC1/2 activation dynamics have not been characterised. Using computational modelling, systems analysis and dynamic simulations we show that DEPTOR confers remarkably rich and complex dynamic behaviours to mTOR signalling, including abrupt, bistable switches, oscillations and co-existing bistable/oscillatory responses. Transitions between these distinct modes of behaviour are enabled by modulating DEPTOR expression alone. We characterise the governing conditions for the observed dynamics by elucidating the network in its vast multi-dimensional parameter space, and develop strategies to identify core network design motifs underlying these dynamics. Our fndings provide new systems-level insights into the complexity of mTOR signalling contributed by DEPTOR. Discovered in the early 1990s as an anti-fungal agent produced by the soil bacterium Streptomyces hygroscopicus, rapamycin has continually surprised scientists with its diverse clinical efects including potent immunosuppres- sive and anti-tumorigenic properties1–3. -

Title Mtorc1 Upregulation Via ERK-Dependent Gene Expression Change Confers Intrinsic Resistance to MEK Inhibitors in Oncogenic Kras-Mutant Cancer Cells

mTORC1 upregulation via ERK-dependent gene expression Title change confers intrinsic resistance to MEK inhibitors in oncogenic KRas-mutant cancer cells. Komatsu, Naoki; Fujita, Yoshihisa; Matsuda, Michiyuki; Aoki, Author(s) Kazuhiro Citation Oncogene (2015), 34(45): 5607-5616 Issue Date 2015-11-05 URL http://hdl.handle.net/2433/207613 This is the accepted manuscrip of the article is available at http://dx.doi.org/10.1038/onc.2015.16.; The full-text file will be made open to the public on 5 May 2016 in accordance with Right publisher's 'Terms and Conditions for Self-Archiving'.; この論 文は出版社版でありません。引用の際には出版社版をご 確認ご利用ください。; This is not the published version. Please cite only the published version. Type Journal Article Textversion author Kyoto University 1 Title mTORC1 upregulation via ERK-dependent gene expression change confers intrinsic resistance to MEK inhibitors in oncogenic KRas-mutant cancer cells. Authors Naoki Komatsu1, Yoshihisa Fujita2, Michiyuki Matsuda1,2, and Kazuhiro Aoki3 Affiliations 1. Laboratory of Bioimaging and Cell Signaling, Graduate School of Biostudies, Kyoto University, Japan 2. Department of Pathology and Biology of Diseases, Graduate School of Medicine, Kyoto University, Japan 3. Imaging Platform for Spatio-Temporal Information, Graduate School of Medicine, Kyoto University, Japan To whom correspondence should be addressed Kazuhiro Aoki, Imaging Platform for Spatio-Temporal Information, Graduate School of Medicine, Kyoto University, Sakyo-ku, Kyoto 606-8501, Japan; Tel.: 81-75-753-9450; Fax: 81-75-753-4698; E-mail: [email protected] Running title (less than 50 letters and spaces): Transcriptional control of mTORC1 activity by ERK 2 Abstract Cancer cells harboring oncogenic BRaf mutants, but not oncogenic KRas mutants, are sensitive to MEK inhibitors (MEKi). -

Differential Expression Profile Analysis of DNA Damage Repair Genes in CD133+/CD133‑ Colorectal Cancer Cells

ONCOLOGY LETTERS 14: 2359-2368, 2017 Differential expression profile analysis of DNA damage repair genes in CD133+/CD133‑ colorectal cancer cells YUHONG LU1*, XIN ZHOU2*, QINGLIANG ZENG2, DAISHUN LIU3 and CHANGWU YUE3 1College of Basic Medicine, Zunyi Medical University, Zunyi; 2Deparment of Gastroenterological Surgery, Affiliated Hospital of Zunyi Medical University, Zunyi;3 Zunyi Key Laboratory of Genetic Diagnosis and Targeted Drug Therapy, The First People's Hospital of Zunyi, Zunyi, Guizhou 563003, P.R. China Received July 20, 2015; Accepted January 6, 2017 DOI: 10.3892/ol.2017.6415 Abstract. The present study examined differential expression cells. By contrast, 6 genes were downregulated and none levels of DNA damage repair genes in COLO 205 colorectal were upregulated in the CD133+ cells compared with the cancer cells, with the aim of identifying novel biomarkers for COLO 205 cells. These findings suggest that CD133+ cells the molecular diagnosis and treatment of colorectal cancer. may possess the same DNA repair capacity as COLO 205 COLO 205-derived cell spheres were cultured in serum-free cells. Heterogeneity in the expression profile of DNA damage medium supplemented with cell factors, and CD133+/CD133- repair genes was observed in COLO 205 cells, and COLO cells were subsequently sorted using an indirect CD133 205-derived CD133- cells and CD133+ cells may therefore microbead kit. In vitro differentiation and tumorigenicity assays provide a reference for molecular diagnosis, therapeutic target in BABA/c nude mice were performed to determine whether selection and determination of the treatment and prognosis for the CD133+ cells also possessed stem cell characteristics, in colorectal cancer.