Ubch7 Regulates 53BP1 Stability and DSB Repair

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

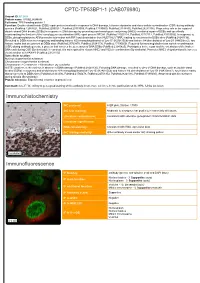

CPTC-TP53BP1-1 (CAB079980) Immunohistochemistry Immunofluorescence

CPTC-TP53BP1-1 (CAB079980) Uniprot ID: Q12888 Protein name: TP53B_HUMAN Full name: TP53-binding protein 1 Function: Double-strand break (DSB) repair protein involved in response to DNA damage, telomere dynamics and class-switch recombination (CSR) during antibody genesis (PubMed:12364621, PubMed:22553214, PubMed:23333306, PubMed:17190600, PubMed:21144835, PubMed:28241136). Plays a key role in the repair of double-strand DNA breaks (DSBs) in response to DNA damage by promoting non-homologous end joining (NHEJ)- mediated repair of DSBs and specifically counteracting the function of the homologous recombination (HR) repair protein BRCA1 (PubMed:22553214, PubMed:23727112, PubMed:23333306). In response to DSBs, phosphorylation by ATM promotes interaction with RIF1 and dissociation from NUDT16L1/TIRR, leading to recruitment to DSBs sites (PubMed:28241136). Recruited to DSBs sites by recognizing and binding histone H2A monoubiquitinated at 'Lys-15' (H2AK15Ub) and histone H4 dimethylated at 'Lys-20' (H4K20me2), two histone marks that are present at DSBs sites (PubMed:23760478, PubMed:28241136, PubMed:17190600). Required for immunoglobulin class-switch recombination (CSR) during antibody genesis, a process that involves the generation of DNA DSBs (PubMed:23345425). Participates in the repair and the orientation of the broken DNA ends during CSR (By similarity). In contrast, it is not required for classic NHEJ and V(D)J recombination (By similarity). Promotes NHEJ of dysfunctional telomeres via interaction with PAXIP1 (PubMed:23727112). Subcellular -

Versatile Roles of K63-Linked Ubiquitin Chains in Trafficking

Cells 2014, 3, 1027-1088; doi:10.3390/cells3041027 OPEN ACCESS cells ISSN 2073-4409 www.mdpi.com/journal/cells Review Versatile Roles of K63-Linked Ubiquitin Chains in Trafficking Zoi Erpapazoglou 1,2, Olivier Walker 3 and Rosine Haguenauer-Tsapis 1,* 1 Institut Jacques Monod-CNRS, UMR 7592, Université-Paris Diderot, Sorbonne Paris Cité, F-75205 Paris, France; E-Mail: [email protected] 2 Current address: Brain and Spine Institute, CNRS UMR 7225, Inserm, U 1127, UPMC-P6 UMR S 1127, 75013 Paris, France 3 Institut des Sciences Analytiques, UMR5280, Université de Lyon/Université Lyon 1, 69100 Villeurbanne, France; E-Mail: [email protected] * Author to whom correspondence should be addressed; E-Mail: [email protected]. External Editor: Hanjo Hellmann Received: 14 July 2014; in revised form: 14 October 2014 / Accepted: 21 October 2014 / Published: 12 November 2014 Abstract: Modification by Lys63-linked ubiquitin (UbK63) chains is the second most abundant form of ubiquitylation. In addition to their role in DNA repair or kinase activation, UbK63 chains interfere with multiple steps of intracellular trafficking. UbK63 chains decorate many plasma membrane proteins, providing a signal that is often, but not always, required for their internalization. In yeast, plants, worms and mammals, this same modification appears to be critical for efficient sorting to multivesicular bodies and subsequent lysosomal degradation. UbK63 chains are also one of the modifications involved in various forms of autophagy (mitophagy, xenophagy, or aggrephagy). Here, in the context of trafficking, we report recent structural studies investigating UbK63 chains assembly by various E2/E3 pairs, disassembly by deubiquitylases, and specifically recognition as sorting signals by receptors carrying Ub-binding domains, often acting in tandem. -

Molecular Profile of Tumor-Specific CD8+ T Cell Hypofunction in a Transplantable Murine Cancer Model

Downloaded from http://www.jimmunol.org/ by guest on September 25, 2021 T + is online at: average * The Journal of Immunology , 34 of which you can access for free at: 2016; 197:1477-1488; Prepublished online 1 July from submission to initial decision 4 weeks from acceptance to publication 2016; doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.1600589 http://www.jimmunol.org/content/197/4/1477 Molecular Profile of Tumor-Specific CD8 Cell Hypofunction in a Transplantable Murine Cancer Model Katherine A. Waugh, Sonia M. Leach, Brandon L. Moore, Tullia C. Bruno, Jonathan D. Buhrman and Jill E. Slansky J Immunol cites 95 articles Submit online. Every submission reviewed by practicing scientists ? is published twice each month by Receive free email-alerts when new articles cite this article. Sign up at: http://jimmunol.org/alerts http://jimmunol.org/subscription Submit copyright permission requests at: http://www.aai.org/About/Publications/JI/copyright.html http://www.jimmunol.org/content/suppl/2016/07/01/jimmunol.160058 9.DCSupplemental This article http://www.jimmunol.org/content/197/4/1477.full#ref-list-1 Information about subscribing to The JI No Triage! Fast Publication! Rapid Reviews! 30 days* Why • • • Material References Permissions Email Alerts Subscription Supplementary The Journal of Immunology The American Association of Immunologists, Inc., 1451 Rockville Pike, Suite 650, Rockville, MD 20852 Copyright © 2016 by The American Association of Immunologists, Inc. All rights reserved. Print ISSN: 0022-1767 Online ISSN: 1550-6606. This information is current as of September 25, 2021. The Journal of Immunology Molecular Profile of Tumor-Specific CD8+ T Cell Hypofunction in a Transplantable Murine Cancer Model Katherine A. -

Characterization of KRAS Rearrangements in Metastatic Prostate Cancer

Published OnlineFirst April 3, 2011; DOI: 10.1158/2159-8274.CD-10-0022 ReseARcH BRieF characterization of KRAS rearrangements in Metastatic Prostate cancer Xiao-Song Wang 1– 3, * Sunita Shankar 1, 3, * Saravana M. Dhanasekaran 1, 3, * Bushra Ateeq 1, 3, Atsuo T. Sasaki 9, 10, Xiaojun Jing 1, 3, Daniel Robinson 1, 3, Qi Cao 1, 3, John R. Prensner 1, 3, Anastasia K. Yocum1, 3, Rui Wang, 1, 3 Daniel F. Fries 1, 3, Bo Han 1, 3, Irfan A. Asangani 1, 3, Xuhong Cao 1, 3, Yong Li 1, 3, Gilbert S. Omenn2 , Dorothee Pflueger 7, 8, Anuradha Gopalan 11, Victor E. Reuter 11, Emily Rose Kahoud 9, Lewis C. Cantley 9, 10, Mark A. Rubin 7, Nallasivam Palanisamy 1, 3, 6, Sooryanarayana Varambally 1, 3, 6, and Arul M. Chinnaiyan 1–6 ABstRAct Using an integrative genomics approach called amplification breakpoint ranking and assembly analysis, we nominated KRAS as a gene fusion with the ubiquitin- conjugating enzyme UBE2L3 in the DU145 cell line, originally derived from prostate cancer metas- tasis to the brain. Interestingly, analysis of tissues revealed that 2 of 62 metastatic prostate cancers harbored aberrations at the KRAS locus. In DU145 cells, UBE2L3-KRAS produces a fusion protein, a specific knockdown of which attenuates cell invasion and xenograft growth. Ectopic ex- pression of the UBE2L3-KRAS fusion protein exhibits transforming activity in NIH 3T3 fibroblasts and RWPE prostate epithelial cells in vitro and in vivo. In NIH 3T3 cells, UBE2L3-KRAS attenuates MEK/ERK signaling, commonly engaged by oncogenic mutant KRAS, and instead signals via AKT and p38 mitogen-activated protein kinase (MAPK) pathways. -

RIDDLE Immunodeficiency Syndrome Is Linked to Defects in 53BP1-Mediated DNA Damage Signaling

RIDDLE immunodeficiency syndrome is linked to defects in 53BP1-mediated DNA damage signaling Grant S. Stewart*†, Tatjana Stankovic*, Philip J. Byrd*, Thomas Wechsler‡, Edward S. Miller*, Aarn Huissoon§, Mark T. Drayson¶, Stephen C. West‡, Stephen J. Elledge†ʈ, and A. Malcolm R. Taylor* *Cancer Research UK, Institute for Cancer Studies, Birmingham University, Vincent Drive, Edgbaston, Birmingham B15 2TT, United Kingdom; ‡Cancer Research UK, Clare Hall Laboratories, London Research Institute, South Mimms, Hertfordshire EN6 3LD, United Kingdom; §Department of Immunology, Birmingham Heartlands Hospital, Birmingham, B9 5SS, United Kingdom; ¶Division of Immunity and Infection, Birmingham University Medical School, Vincent Drive, Edgbaston, Birmingham B15 2TT, United Kingdom; and ʈHoward Hughes Medical Institute, Department of Genetics, Harvard Partners Center for Genetics and Genomics, Harvard Medical School, 77 Avenue Louis Pasteur, Boston, MA 02115 Contributed by Stephen J. Elledge, September 6, 2007 (sent for review July 6, 2007) Cellular DNA double-strand break-repair pathways have evolved with an alternative constant region (e.g., ␣, ␥, ) to generate to protect the integrity of the genome from a continual barrage of different Ig isotypes e.g., IgA, IgG, and IgE (2). potentially detrimental insults. Inherited mutations in genes that During the process of CSR, it has been hypothesized that two control this process result in an inability to properly repair DNA closely positioned single-stranded DNA nicks result in the damage, ultimately -

1 Supporting Information for a Microrna Network Regulates

Supporting Information for A microRNA Network Regulates Expression and Biosynthesis of CFTR and CFTR-ΔF508 Shyam Ramachandrana,b, Philip H. Karpc, Peng Jiangc, Lynda S. Ostedgaardc, Amy E. Walza, John T. Fishere, Shaf Keshavjeeh, Kim A. Lennoxi, Ashley M. Jacobii, Scott D. Rosei, Mark A. Behlkei, Michael J. Welshb,c,d,g, Yi Xingb,c,f, Paul B. McCray Jr.a,b,c Author Affiliations: Department of Pediatricsa, Interdisciplinary Program in Geneticsb, Departments of Internal Medicinec, Molecular Physiology and Biophysicsd, Anatomy and Cell Biologye, Biomedical Engineeringf, Howard Hughes Medical Instituteg, Carver College of Medicine, University of Iowa, Iowa City, IA-52242 Division of Thoracic Surgeryh, Toronto General Hospital, University Health Network, University of Toronto, Toronto, Canada-M5G 2C4 Integrated DNA Technologiesi, Coralville, IA-52241 To whom correspondence should be addressed: Email: [email protected] (M.J.W.); yi- [email protected] (Y.X.); Email: [email protected] (P.B.M.) This PDF file includes: Materials and Methods References Fig. S1. miR-138 regulates SIN3A in a dose-dependent and site-specific manner. Fig. S2. miR-138 regulates endogenous SIN3A protein expression. Fig. S3. miR-138 regulates endogenous CFTR protein expression in Calu-3 cells. Fig. S4. miR-138 regulates endogenous CFTR protein expression in primary human airway epithelia. Fig. S5. miR-138 regulates CFTR expression in HeLa cells. Fig. S6. miR-138 regulates CFTR expression in HEK293T cells. Fig. S7. HeLa cells exhibit CFTR channel activity. Fig. S8. miR-138 improves CFTR processing. Fig. S9. miR-138 improves CFTR-ΔF508 processing. Fig. S10. SIN3A inhibition yields partial rescue of Cl- transport in CF epithelia. -

The Role of Ubiquitination in NF-Κb Signaling During Virus Infection

viruses Review The Role of Ubiquitination in NF-κB Signaling during Virus Infection Kun Song and Shitao Li * Department of Microbiology and Immunology, Tulane University, New Orleans, LA 70112, USA; [email protected] * Correspondence: [email protected] Abstract: The nuclear factor κB (NF-κB) family are the master transcription factors that control cell proliferation, apoptosis, the expression of interferons and proinflammatory factors, and viral infection. During viral infection, host innate immune system senses viral products, such as viral nucleic acids, to activate innate defense pathways, including the NF-κB signaling axis, thereby inhibiting viral infection. In these NF-κB signaling pathways, diverse types of ubiquitination have been shown to participate in different steps of the signal cascades. Recent advances find that viruses also modulate the ubiquitination in NF-κB signaling pathways to activate viral gene expression or inhibit host NF-κB activation and inflammation, thereby facilitating viral infection. Understanding the role of ubiquitination in NF-κB signaling during viral infection will advance our knowledge of regulatory mechanisms of NF-κB signaling and pave the avenue for potential antiviral therapeutics. Thus, here we systematically review the ubiquitination in NF-κB signaling, delineate how viruses modulate the NF-κB signaling via ubiquitination and discuss the potential future directions. Keywords: NF-κB; polyubiquitination; linear ubiquitination; inflammation; host defense; viral infection Citation: Song, K.; Li, S. The Role of 1. Introduction Ubiquitination in NF-κB Signaling The nuclear factor κB (NF-κB) is a small family of five transcription factors, including during Virus Infection. Viruses 2021, RelA (also known as p65), RelB, c-Rel, p50 and p52 [1]. -

WO 2019/079361 Al 25 April 2019 (25.04.2019) W 1P O PCT

(12) INTERNATIONAL APPLICATION PUBLISHED UNDER THE PATENT COOPERATION TREATY (PCT) (19) World Intellectual Property Organization I International Bureau (10) International Publication Number (43) International Publication Date WO 2019/079361 Al 25 April 2019 (25.04.2019) W 1P O PCT (51) International Patent Classification: CA, CH, CL, CN, CO, CR, CU, CZ, DE, DJ, DK, DM, DO, C12Q 1/68 (2018.01) A61P 31/18 (2006.01) DZ, EC, EE, EG, ES, FI, GB, GD, GE, GH, GM, GT, HN, C12Q 1/70 (2006.01) HR, HU, ID, IL, IN, IR, IS, JO, JP, KE, KG, KH, KN, KP, KR, KW, KZ, LA, LC, LK, LR, LS, LU, LY, MA, MD, ME, (21) International Application Number: MG, MK, MN, MW, MX, MY, MZ, NA, NG, NI, NO, NZ, PCT/US2018/056167 OM, PA, PE, PG, PH, PL, PT, QA, RO, RS, RU, RW, SA, (22) International Filing Date: SC, SD, SE, SG, SK, SL, SM, ST, SV, SY, TH, TJ, TM, TN, 16 October 2018 (16. 10.2018) TR, TT, TZ, UA, UG, US, UZ, VC, VN, ZA, ZM, ZW. (25) Filing Language: English (84) Designated States (unless otherwise indicated, for every kind of regional protection available): ARIPO (BW, GH, (26) Publication Language: English GM, KE, LR, LS, MW, MZ, NA, RW, SD, SL, ST, SZ, TZ, (30) Priority Data: UG, ZM, ZW), Eurasian (AM, AZ, BY, KG, KZ, RU, TJ, 62/573,025 16 October 2017 (16. 10.2017) US TM), European (AL, AT, BE, BG, CH, CY, CZ, DE, DK, EE, ES, FI, FR, GB, GR, HR, HU, ΓΕ , IS, IT, LT, LU, LV, (71) Applicant: MASSACHUSETTS INSTITUTE OF MC, MK, MT, NL, NO, PL, PT, RO, RS, SE, SI, SK, SM, TECHNOLOGY [US/US]; 77 Massachusetts Avenue, TR), OAPI (BF, BJ, CF, CG, CI, CM, GA, GN, GQ, GW, Cambridge, Massachusetts 02139 (US). -

The UBE2L3 Ubiquitin Conjugating Enzyme: Interplay with Inflammasome Signalling and Bacterial Ubiquitin Ligases

The UBE2L3 ubiquitin conjugating enzyme: interplay with inflammasome signalling and bacterial ubiquitin ligases Matthew James George Eldridge 2018 Imperial College London Department of Medicine Submitted to Imperial College London for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy 1 Abstract Inflammasome-controlled immune responses such as IL-1β release and pyroptosis play key roles in antimicrobial immunity and are heavily implicated in multiple hereditary autoimmune diseases. Despite extensive knowledge of the mechanisms regulating inflammasome activation, many downstream responses remain poorly understood or uncharacterised. The cysteine protease caspase-1 is the executor of inflammasome responses, therefore identifying and characterising its substrates is vital for better understanding of inflammasome-mediated effector mechanisms. Using unbiased proteomics, the Shenoy grouped identified the ubiquitin conjugating enzyme UBE2L3 as a target of caspase-1. In this work, I have confirmed UBE2L3 as an indirect target of caspase-1 and characterised its role in inflammasomes-mediated immune responses. I show that UBE2L3 functions in the negative regulation of cellular pro-IL-1 via the ubiquitin- proteasome system. Following inflammatory stimuli, UBE2L3 assists in the ubiquitylation and degradation of newly produced pro-IL-1. However, in response to caspase-1 activation, UBE2L3 is itself targeted for degradation by the proteasome in a caspase-1-dependent manner, thereby liberating an additional pool of IL-1 which may be processed and released. UBE2L3 therefore acts a molecular rheostat, conferring caspase-1 an additional level of control over this potent cytokine, ensuring that it is efficiently secreted only in appropriate circumstances. These findings on UBE2L3 have implications for IL-1- driven pathology in hereditary fever syndromes, and autoinflammatory conditions associated with UBE2L3 polymorphisms. -

PRODUCT INFORMATION TP53BP1 BRCT Domains (Human Recombinant) Item No

PRODUCT INFORMATION TP53BP1 BRCT domains (human recombinant) Item No. 14171 • Batch No. XXXX Overview and Properties Synonyms: Tumor Protein p53 binding Protein 1, Tumor Suppressor p53-binding Protein 1 Source: Recombinant human N-terminal GST-tagged protein expressed in E. coli amino acids 1,717-1,972 (N- and C-terminal truncation) Uniprot No.: Q12888 Batch specific information can be found on the Batch Specific Insert or by contacting Technical Support Molecular Weight: 55.1 kDa Storage: -80°C (as supplied) Stability: ≥6 months Purity: batch specific Supplied in: 50 mM Tris-HCl, pH 8.0, containing 150 mM sodium chloride and 20% glycerol Protein Concentration: batch specific mg/ml Image(s) 1 2 3 4 250 kDa · · · · · · · 150 kDa · · · · · · · 100 kDa · · · · · · · 75 kDa · · · · · · · 50 kDa · · · · · · · 37 kDa · · · · · · · 25 kDa · · · · · · · 20 kDa · · · · · · · Lane 1: MW Markers Lane 2: TP53BP1 BRCT domains (1 µg) Lane 3: TP53BP1 BRCT domains (2 µg) Lane 4: TP53BP1 BRCT domains (5 µg) Representative gel image shown; actual purity may vary between each batch. WARNING CAYMAN CHEMICAL THIS PRODUCT IS FOR RESEARCH ONLY - NOT FOR HUMAN OR VETERINARY DIAGNOSTIC OR THERAPEUTIC USE. 1180 EAST ELLSWORTH RD SAFETY DATA ANN ARBOR, MI 48108 · USA This material should be considered hazardous until further information becomes available. Do not ingest, inhale, get in eyes, on skin, or on clothing. Wash thoroughly after handling. Before use, the user must review the complete Safety Data Sheet, which has been sent via email to your institution. PHONE: [800] 364-9897 WARRANTY AND LIMITATION OF REMEDY [734] 971-3335 Buyer agrees to purchase the material subject to Cayman’s Terms and Conditions. -

Tumor Suppressor and DNA Damage Response Panel 2

Tumor suppressor and DNA damage response panel 2 (55 analytes) Gene Symbol Target protein name UniProt ID (& link) Modification* *blanks mean the assay detects the ACT Actin; ACTA2 ACTA1 ACTB ACTG1 ACTC1 ACTG2 Q562L2 non‐modified peptide sequence CASC5 cancer susceptibility candidate 5 Q8NG31 pS767 CASC5 cancer susceptibility candidate 5 Q8NG31 CASP3 caspase 3, apoptosis‐related cysteine peptidase P42574 pS26 CDC25B cell division cycle 25 homolog B (S. pombe) P30305 pS16 CDC25B cell division cycle 25 homolog B (S. pombe) P30305 pS323 CDC25B cell division cycle 25 homolog B (S. pombe) P30305 CDC25C cell division cycle 25 homolog B (S. pombe) P30307 pS216 CDC25C cell division cycle 25 homolog B (S. pombe) P30307 CDCA8 cell division cycle associated 8 Q53HL2 pT16 CDK1 cyclin‐dependent kinase 1 P06493 pT161 CDK1 cyclin‐dependent kinase 1 P06493 CDK7 cyclin‐dependent kinase 7 P50613 pT17 CHEK1 CHK1 checkpoint homolog (S. pombe) O14757 pS286 CHEK2 CHK2 checkpoint homolog (S. pombe) O96017 pS379 CHEK2 CHK2 checkpoint homolog (S. pombe) O96017 pT387 CHEK2 CHK2 checkpoint homolog (S. pombe) O96017 GAPDH Glyceraldehyde‐3‐phosphate dehydrogenase P04406 LAT linker for activation of T cells O43561 pS224 LMNB1 lamin B1 P20700 pT2; pS23 LMNB1 lamin B1 P20700 pT2 LMNB1 lamin B1 P20700 pS23 MCM6 minichromosome maintenance complex component 6 Q14566 pS762 MCM6 minichromosome maintenance complex component 6 Q14566 MDM2 Mdm2, transformed 3T3 cell double minute 2, p53 binding protein (mouse) Q00987 pS166 MDM2 Mdm2, transformed 3T3 cell double minute 2, p53 binding protein (mouse) Q00987 MKI67 antigen identified by monoclonal antibody Ki‐67 P46013 pT181 MKI67 antigen identified by monoclonal antibody Ki‐67 P46013 MKI67 antigen identified by monoclonal antibody Ki‐67 P46013 pT246 MRE11A MRE11 meiotic recombination 11 homolog A (S. -

Targeted Mass Spectrometry Enables Quantification of Novel

cancers Article Targeted Mass Spectrometry Enables Quantification of Novel Pharmacodynamic Biomarkers of ATM Kinase Inhibition Jeffrey R. Whiteaker 1 , Tao Wang 1, Lei Zhao 1, Regine M. Schoenherr 1, Jacob J. Kennedy 1, Ulianna Voytovich 1, Richard G. Ivey 1, Dongqing Huang 1, Chenwei Lin 1, Simona Colantonio 2, Tessa W. Caceres 2, Rhonda R. Roberts 2, Joseph G. Knotts 2, Jan A. Kaczmarczyk 2, Josip Blonder 2, Joshua J. Reading 2, Christopher W. Richardson 2, Stephen M. Hewitt 3, Sandra S. Garcia-Buntley 2, William Bocik 2, Tara Hiltke 4, Henry Rodriguez 4, Elizabeth A. Harrington 5, J. Carl Barrett 5, Benedetta Lombardi 5, Paola Marco-Casanova 5, Andrew J. Pierce 5 and Amanda G. Paulovich 1,* 1 Fred Hutchinson Cancer Research Center, Clinical Research Division, Seattle, WA 98109, USA; [email protected] (J.R.W.); [email protected] (T.W.); [email protected] (L.Z.); [email protected] (R.M.S.); [email protected] (J.J.K.); [email protected] (U.V.); [email protected] (R.G.I.); [email protected] (D.H.); [email protected] (C.L.) 2 Cancer Research Technology Program, Antibody Characterization Lab, Frederick National Laboratory for Cancer Research, Frederick, MD 21701, USA; [email protected] (S.C.); [email protected] (T.W.C.); [email protected] (R.R.R.); [email protected] (J.G.K.); [email protected] (J.A.K.); [email protected] (J.B.); [email protected] (J.J.R.); [email protected] (C.W.R.); [email protected] (S.S.G.-B.); [email protected] (W.B.) 3 Experimental Pathology Laboratory, Laboratory of Pathology, Center for Cancer Research, National Cancer Citation: Whiteaker, J.R.; Wang, T.; Institute, National Institute of Health, Bethesda, MD 20892, USA; [email protected] Zhao, L.; Schoenherr, R.M.; Kennedy, 4 Office of Cancer Clinical Proteomics Research, National Cancer Institute, Bethesda, MD 20892, USA; J.J.; Voytovich, U.; Ivey, R.G.; Huang, [email protected] (T.H.); [email protected] (H.R.) D.; Lin, C.; Colantonio, S.; et al.