1 Introduction to International and Global Studies Shawn Smallman

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Digital Edition

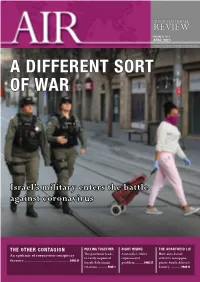

AUSTRALIA/ISRAEL REVIEW VOLUME 45 No. 4 APRIL 2020 AUSTRALIA/ISRAEL & JEWISH AFFAIRS COUNCIL A DIFFERENT SORT OF WAR Israel’s military enters the battle against coronavirus THE OTHER CONTAGION PULLING TOGETHER RIGHT RISING THE APARTHEID LIE An epidemic of coronavirus conspiracy The pandemic leads Australia’s white How anti-Israel to vastly improved supremacist activists misappro- theories ............................................... PAGE 21 Israeli-Palestinian problem ........PAGE 27 priate South Africa’s relations .......... PAGE 7 history ........... PAGE 31 WITH COMPLIMENTS NAME OF SECTION L1 26 BEATTY AVENUE ARMADALE VIC 3143 TEL: (03) 9661 8250 FAX: (03) 9661 8257 WITH COMPLIMENTS 2 AIR – April 2020 AUSTRALIA/ISRAEL VOLUME 45 No. 4 REVIEW APRIL 2020 EDITOR’S NOTE NAME OF SECTION his AIR edition focuses on the Israeli response to the extraordinary global coronavirus ON THE COVER Tpandemic – with a view to what other nations, such as Australia, can learn from the Israeli Border Police patrol Israeli experience. the streets of Jerusalem, 25 The cover story is a detailed look, by security journalist Alex Fishman, at how the IDF March 2020. Israeli authori- has been mobilised to play a part in Israel’s COVID-19 response – even while preparing ties have tightened citizens’ to meet external threats as well. In addition, Amotz Asa-El provides both a timeline of movement restrictions to Israeli measures to meet the coronavirus crisis, and a look at how Israel’s ongoing politi- prevent the spread of the coronavirus that causes the cal standoff has continued despite it. Plus, military reporter Anna Ahronheim looks at the COVID-19 disease. (Photo: Abir Sultan/AAP) cooperation the emergency has sparked between Israel and the Palestinians. -

June 12, 2016, Hillary Clinton Candidate for President. a Third

HILLARY CLINTON CANDIDATE FOR PRESIDENT. A THIRD ANTHOLOGY OF CRITIQUES PRO AND CON PUBLISHED DURING HER CAMPAIGN FOR PRESIDENT 2015-2016. http://jamesrichardbennett.blogspot.com/2016/06/hillary-clinton- critiques-3.html Compiled by Dick Bennett. June 12, 2016. (#1, June 12, 2015; #2 Feb. 19, 2016) http://omnicenter.org/donate/ Contents 3rd Anthology, Publications first half of 2016. (I supported Bernie during the primaries. –Dick) Get the Facts Clinton a Progressive? Endorsements Sierra Club (with Joyce’s satire) NOW President Obama Elizabeth Warren LOCAL CRITICISM Dick, Joyce, Art National Criticism Chomsky Johnstone, Queen of Chaos Kreitner, ed. Who Is Hillary Clinton? William Blum, He’ll Vote for Trump Common Dreams, Sanders Better for World Peace Karlin, Clinton Supported Military Coup in Honduras Hillary and Israel: She is Pro-Netanyahu Blacks Should Support Bernie Greenpeace Asks HC to Oppose Fossil Fuel Money Checking the Facts PolitiFact: Fact-checking US politics www.politifact.com/ https://www.google.com/search?rls=aso&client=gmail&q=politifact&authuser=0 PolitiFact.com is a project of the Tampa Bay Times to help you find the truth in Washington and the Obama presidency. Truth-O-Meter TM Pants on Fire! - False - True Barack Obama Joe Biden's file Hillary Clinton Donald Trump PolitiFact (@PolitiFact) | Twitter https://twitter.com/PolitiFact HILLARY CLINTON A PROGRESSIVE? Google Hillary Clinton's Progressive Values for a bit of the debate. She defines it differently. Endorsements 2016 ENDORSEMENTS OF HC List of Hillary Clinton presidential campaign endorsements, 2016 ... https://en.wikipedia.org/.../List_of_ Hillary _ Clinton _ presidentia... Wikipedia This is a list of notable individuals and organizations who have voiced thei r endorsement of Hillary Clinton as the Democratic Party's presidential nominee for the . -

Why They Died Civilian Casualties in Lebanon During the 2006 War

September 2007 Volume 19, No. 5(E) Why They Died Civilian Casualties in Lebanon during the 2006 War Map: Administrative Divisions of Lebanon .............................................................................1 Map: Southern Lebanon ....................................................................................................... 2 Map: Northern Lebanon ........................................................................................................ 3 I. Executive Summary ........................................................................................................... 4 Israeli Policies Contributing to the Civilian Death Toll ....................................................... 6 Hezbollah Conduct During the War .................................................................................. 14 Summary of Methodology and Errors Corrected ............................................................... 17 II. Recommendations........................................................................................................ 20 III. Methodology................................................................................................................ 23 IV. Legal Standards Applicable to the Conflict......................................................................31 A. Applicable International Law ....................................................................................... 31 B. Protections for Civilians and Civilian Objects ...............................................................33 -

OF LEBANON: WHAT WIKILEAKS TELLS US ABOUT AMERICAN EFFORTS to FIND an ALTERNATIVE to HIZBALLAH December 22, 2011 Gloria-Center.Org

http://www.gloria-center.org/2011/12/the-%e2%80%9cindependent-shi%e2%80%99a%e2%80%9d-of-lebanon-what-wikileaks-tells-us-about-american-efforts-to-find-an-alternative-to-hizballah/ THE “INDEPENDENT SHI’A” OF LEBANON: WHAT WIKILEAKS TELLS US ABOUT AMERICAN EFFORTS TO FIND AN ALTERNATIVE TO HIZBALLAH December 22, 2011 gloria-center.org By Phillip Smyth U.S. diplomatic cables released by Wikileaks have given a new insight into American policy in Lebanon, especially efforts to counter Hizballah. Hizballah’s willingness to use a combination of hard power through violence and coercion, combined with a softer touch via extensive patronage networks has given them unmatched control over the Shi’a community since the 2005 Cedar Revolution. Using these released cables, this study will focus on efforts, successes, and failures made by so-called “independent” Shi’i political organizations, religious groups, and NGOs to counter Hizballah’s pervasive influence among Lebanon’s Shi’a. I sat in on a fascinating meeting yesterday with some independent Shia Muslims – that is to say, Shias who are trying to fight against Hezbollah’s influence in Lebanon. They’re an admirable group of people, really on the front lines of history in a pretty gripping way… To make a long story short, the March 14 coalition pretty much screwed them… However: you know how everyone says Lebanon is so complicated? Well, it is, but once you understand a few basic particulars on why things are structured as they are, it’s really not so different from other places. – Michael Tomasky, American journalist, March 13, 2009.[1] INTRODUCTION Leaked cables emanating from Wikileaks have provided a unique insight into a realm of U.S. -

Spillover from the Conflict in Syria

CHILDREN AND FAMILIES The RAND Corporation is a nonprofit institution that EDUCATION AND THE ARTS helps improve policy and decisionmaking through ENERGY AND ENVIRONMENT research and analysis. HEALTH AND HEALTH CARE This electronic document was made available from INFRASTRUCTURE AND www.rand.org as a public service of the RAND TRANSPORTATION Corporation. INTERNATIONAL AFFAIRS LAW AND BUSINESS NATIONAL SECURITY Skip all front matter: Jump to Page 16 POPULATION AND AGING PUBLIC SAFETY SCIENCE AND TECHNOLOGY Support RAND Purchase this document TERRORISM AND HOMELAND SECURITY Browse Reports & Bookstore Make a charitable contribution For More Information Visit RAND at www.rand.org Explore the RAND National Defense Research Institute View document details Limited Electronic Distribution Rights This document and trademark(s) contained herein are protected by law as indicated in a notice appearing later in this work. This electronic representation of RAND intellectual property is provided for non-commercial use only. Unauthorized posting of RAND electronic documents to a non-RAND website is prohibited. RAND electronic documents are protected under copyright law. Permission is required from RAND to reproduce, or reuse in another form, any of our research documents for commercial use. For information on reprint and linking permissions, please see RAND Permissions. This report is part of the RAND Corporation research report series. RAND reports present research findings and objective analysis that address the challenges facing the public and private sectors. All RAND reports undergo rigorous peer review to ensure high standards for re- search quality and objectivity. Spillover from the Conflict in Syria An Assessment of the Factors that Aid and Impede the Spread of Violence William Young, David Stebbins, Bryan A. -

Raisina Files

VOLUME 04 • JANUARY 2019 2019 RAISINA FILES Debating Future Frameworks in a Disrupted World EDITED BY RITIKA PASSI Raisina Files is an annual ORF publication that brings together emerging and established voices in a collection of essays. These essays strive to engage readers on key, contemporary questions that are implicating the world and India. Arguments presented in this collection will be useful in taking conversations forward and enunciating policy suggestions for an evolving Asian and world order. The views expressed in this publication are those of the individual authors. © Observer Research Foundation 2019 ISBN: 978-93-88262-72-9 Layout and Typeset: Anuj Malhotra (www.fantomas.in) Printer: Vinset Advertising, New Delhi RAISINA FILES Debating Future Frameworks in a Disrupted World EDITED BY RITIKA PASSI IN THIS VOLUME n 2019, US-China trading blows will become a full- implications bearing heavily on how states are engaging blown trade war. The two will also clash, military with one another. and politically, in the Indo-Pacific as competition, Governance and cooperation is becoming harder, claims Icontainment, and counter-containment come to a head. the US National Intelligence Council’s latest Global Conflict across the middle spaces of the Eurasian landmass Trends, and the conclusion passes muster particularly in the will not be far behind, thanks to the US withdrawal from face of flailing existing and legacy systems and mechanisms. the Iran nuclear deal, potential resurgence of Shia-Sunni It can be argued, however, that in crisis and chaos — in violence, and flaring up of tensions in eastern Ukraine, the very recognition of fault-lines and fractures — lie the between Armenia and Azerbaijan, and in Afghanistan. -

NHBS Trade Catalogue NHBS Is the World's Leading Distributor of Wildlife, Science and Natural History Books

NHBS Trade Catalogue NHBS is the world's leading distributor of wildlife, science and natural history books. The NHBS Trade Catalogue is an up-to-date list of all the titles we distribute on behalf of leading conservation and scientific organisations - including BirdLife International, RSPB, The Mammal Society, British Trust for Ornithology, Bat Conservation Trust, Wetlands International and Conservation International. We also provide distribution for hundreds of small and independent natural history publishers from around the world. If you are a publisher and would like us to distribute your book, please send an email to [email protected] Trade terms are available for library suppliers, book wholesalers, bookshops, visitor centres, general wildlife shops, garden centres and other retailers. For information on ordering trade titles, or to set up a trade account, please contact us. Tel:+44 (0)1803 865913 Fax:+44 (0)1803 865280 [email protected] NHBS Ltd, 1-6 The Stables, Ford Road, Totnes, Devon, TQ9 5LE, UK Mammals Veldgids Europese Zoogdieren [Field Guide to European Mammals] 368 pages | colour photos, colour & b/w illustrations, colour Peter Twisk(Author), Annemarie van Diepenbeek(Author), Jan Piet Bekker(Author), Jos distribution maps | KNNV Uitgeverij Teeuwisse(Author) Hardback 2019 9789050116879 #245394 £31.99 Std disc This practical mammal guide is intended both as a field guide and a reference work at home. It brings together all the mammals of Europe and their tracks in a beautifully edited guide, including species new to Europe such as the Levant mole and the... A Review of the Population and Conservation Status of British Mammals 699 pages | b/w illustrations, colour distribution maps, colour & Fiona Mathews(Author), Laura M Kubasiewicz(Author), John Gurnell(Author), Colin A b/w tables | The Mammal Society Harrower(Author), RA McDonald(Author), RF Shore(Author) Paperback 2018 9781783544943 #245158 £59.99 Std disc This report presents the first comprehensive review of the status of British mammal populations for over 20 years. -

Received by NSD/FARA Registration Unit 07/22/2013 3:14:07 PM OMB NO

Received by NSD/FARA Registration Unit 07/22/2013 3:14:07 PM OMB NO. 1124-0002; Expires February 28,2014 U.S. Department of Justice Supplemental Statement Washington, DC 20530 Pursuant to the Foreign Agents Registration Act of 1938, as amended For Six Month Period Ending 05/31/2013 (Insert date) I - REGISTRANT 1. (a) Name of Registrant (b) Registration No. Fabiani & Company 6045 (c) Business Address(es) of Registrant 1101 Pennsylvania Avenue, NW Suite 700 Washington, DC 20004 2. Has there been a change in the information previously furnished in connection with the following? (a) If an individual: (1) Residence address(es) YesD NoD (2) Citizenship . YesD NoD (3) Occupation YesD NoD (b) If an organization: (1) Name YesD No0 (2) Ownership or control YesD No0 (3) Branch offices YesD No 0 (c) Explain fully all changes, if any, indicated in Items (a) and (b) above. IF THE REGISTRANT IS AN INDIVIDUAL, OMIT RESPONSE TO ITEMS 3, 4, AND 5(a). 3. If you have previously filed Exhibit C1, state whether any changes therein have occurred during this 6 month reporting period. Yes • No El If yes, have you filed an amendment to the Exhibit C? Yes • No • If no, please attach the required amendment. 1 The Exhibit C, for which no printed form is provided, consists of a true copy ofthe charter, articles of incorporation, association, and by laws of a registrant that is an organization. (A waiver ofthe requirement to file an Exhibit C may be obtained for good cause upon written application to the Assistant Attorney General, National Security Division, U.S. -

The Insecure City

THE INSECURE CITY THE INSECURE CITY Space, Power, and Mobility in Beirut Kristin V. Monroe Rutgers University Press New Brunswick, New Jersey, and London Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data Monroe, Kristin V., 1974– author. Th e insecure city : space, power, and mobility in Beirut / Kristin V. Monroe. pages cm Includes bibliographical references and index. ISBN 978–0–8135–7463–9 (hardcover : alk. paper) — ISBN 978–0–8135–7462–2 (pbk. : alk. paper) — ISBN 978–0–8135–7464–6 (e-book (epub)) — ISBN 978–0–8135–7465–3 (e-book (web pdf)) 1. Sociology, Urban —Lebanon—Beirut. 2. Public spaces—Lebanon— Beirut. 3. City traffi c—Lebanon—Beirut. 4. Violence—Lebanon—Beirut. 5. Urban anthropology—Lebanon—Beirut. 6. Beirut (Lebanon)—Social conditions. I. Title. HT147.L4M66 2016 307.76095692′5—dc23 2015021869 A British Cataloging-in-Publication record for this book is available from the British Library. Copyright © 2016 by Kristin V. Monroe All rights reserved No part of this book may be reproduced or utilized in any form or by any means, electronic or mechanical, or by any information storage and retrieval system, without writt en permission from the publisher. Please contact Rutgers University Press, 106 Somerset Street, New Brunswick, NJ 08901. Th e only exception to this prohibition is “fair use” as defi ned by U.S. copyright law. Visit our website: htt p://rutgerspress.rutgers.edu Manufactured in the United States of America For my mother, Ann CONTENTS List of Figures ix Acknowledgments xi Note on Language xv Introduction 1 1 Th e Privatized City 18 2 Th e Space of War 35 3 Politics and Public Space 56 4 Securing Beirut 79 5 Th e Chaos of Driving 101 6 “Th ere Is No State” 121 Conclusion 139 Notes 145 References 165 Index 177 vii FIGURES Figure I.1 Internal Security Forces billboard 15 Figure 1.1 Map of Beirut in Lebanon and the region 19 Figure 1.2 Neighborhood map of Beirut 20 Figure 1.3 Cafe at a Beirut public garden during the late Ott oman period, ca. -

Kurdish Identity, Local Power Politics and the Future of Iraqi Federalism

Gillette, 1 Robert Gillette Insurgency and Counter-Insurgency Prof. Ben Jensen May 1, 2010 The Gravest Danger: Kurdish Identity, Local Power Politics and the Future of Iraqi Federalism Gillette, 2 Abstract: The impending withdraw of American forces from Iraq will leave the country in the hands of what amounts to two separate military forces: Iraq’s national armed forces and those of the Kurdish Regional Government. Integral to the Iraqi federalist bargain is the autonomy of the Kurdistan region, which includes independent control over the Kurdish military, the Peshmerga . The standing tensions between Peshmerga forces and the Iraqi army along the so called trigger- line attest to the potential dangers the situation poses. This paper explores the reasons why the integration of the Peshmega into the Iraqi national armed forces has not nor is likely to occur. It examines the hypothesis that a combination of identity politics, territorial disputes and local power structures has effectively prohibited integration for the immediate future. Robert Gillette University Honors in International Studies Capstone Advisor: Prof. Benjamin Jensen Gillette, 3 Introduction/Justification for Research: “The Kurds will participate in the election as Kurds and, if we fail to come to an agreement with the Iraqi political forces, we will participate as Kurdistanis.” – Massoud Barzani, 2004 (as quoted by Olson, 2007. 223) 1 Commander of U.S. Forces Iraq General Ray Odierno has publically stated that he considers the Arab-Kurdish tensions to be the single largest threat to the country’s security and stability (Chon, 2009). This is certainly true at least in terms of the magnitude of the repercussions. -

The Truth About Egypt | the Washington Institute

MENU Policy Analysis / Interviews and Presentations The Truth About Egypt by Eric Trager Aug 15, 2013 ABOUT THE AUTHORS Eric Trager Eric Trager was the Esther K. Wagner Fellow at The Washington Institute. Michael Totten, a contributing editor for World Affairs, interviews Dr. Trager regarding the direction of Egypt's political dynamics since Morsi's ouster. gypt looks dodgier than ever right now. Just six weeks after overthrowing the government in a military coup, E the armed forces opened fire on civilians protesting the removal of President Mohammad Morsi and killed more than 500 people, prompting President Barack Obama to cancel joint American-Egyptian military drills. Springtime never came to Cairo at all. In some ways, Egypt is right back where it was when Hosni Mubarak still ruled the country. The political scene is exactly the same. Two illiberal titans -- a military regime and an Islamist opposition -- are battling it out. But in other ways, Egypt is in worse shape now than it was. It's more chaotic, more violent. Its economy is imploding, its people increasingly desperate. I recently interviewed Eric Trager, a scholar at the Washington Institute for Near East Policy. He's a real expert on Egypt and has been more consistently right than just about anyone. He called out the Muslim Brotherhood as an inherently authoritarian organization while scores of other supposed "experts" falsely pimped it as moderate. And contrary to claims from the opposing camp, that the army "restored" democracy with its coup, he saw the recent bloody unpleasantness coming well in advance. I spoke to him before this week's massacre happened, but it's clear from his remarks that he suspected something like it was coming. -

The Anbar Awakening: an Alliance of Incentives

John A. McCary The Anbar Awakening: An Alliance of Incentives The now-deceased leader of the Anbar Awakening, Sheikh Abd al Sittar Abu Reesha, once said, ‘‘Our American friends had not understood us when they came. They were proud, stubborn people and so were we. They worked with the opportunists, now they have turned to the tribes, and this is as it should be.’’1 Until 2007, the most violent region of insurgent attacks against U.S. forces in Iraq had been al Anbar, the largely rural, expansive western province stretching from the outskirts of Baghdad to Iraq’s lengthy, mostly unsecured desert borders with Sunni-dominated Jordan, Saudi Arabia, and Syria.2 In what is most easily described as a marriage of convenience, Sunni insurgents and foreign Sunni al Qaeda fighters in al Anbar had formed a strategic and tactical alliance against what was perceived as an occupation by the United States or, more pointedly, against the occupation of a Muslim land by a largely Christian force, a deep affront to traditional Muslim values harkening back to the Crusades of the Middle Ages.3 Iraqis in al Anbar provided local knowledge, logistics, and up to 95 percent of the personnel, while experienced foreign al Qaeda fighters provided training, expertise, and financing. The pitch was simple: ‘‘We are Sunni. You are Sunni. The Americans and Iranians are helping the Shi‘a*let/ ’s fight them together.’’ 4 Yet, as al Qaeda mounted a campaign of deadly intimidation, and slowly but surely began taking control of money-making activities traditionally held by the tribes, this alliance began to wear thin.