The Problem with the Influence of the Moving Image in Society Today, the Alter-Modern and the Disappearance of a Focus on the Internal

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Postmillennial Trends in Anglophone Literatures, Cultures and Media

Postmillennial Trends in Anglophone Literatures, Cultures and Media Postmillennial Trends in Anglophone Literatures, Cultures and Media Edited by Soňa Šnircová and Slávka Tomaščíková Postmillennial Trends in Anglophone Literatures, Cultures and Media Edited by Soňa Šnircová and Slávka Tomaščíková This book first published 2019 Cambridge Scholars Publishing Lady Stephenson Library, Newcastle upon Tyne, NE6 2PA, UK British Library Cataloguing in Publication Data A catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library Copyright © 2019 by Soňa Šnircová, Slávka Tomaščíková and contributors All rights for this book reserved. No part of this book may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted, in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording or otherwise, without the prior permission of the copyright owner. ISBN (10): 1-5275-2709-3 ISBN (13): 978-1-5275-2709-6 TABLE OF CONTENTS Introduction ................................................................................................. 1 Postmillennial Trends in Anglophone Literatures, Cultures and Media Soňa Šnircová and Slávka Tomaščíková Part I: Addressing the Theories of a New Cultural Paradigm Chapter One ............................................................................................... 16 Metamodernism for Children?: A Performatist Rewriting of Gabriel García Márquez’s ‘A Very Old Man With Enormous Wings: A Tale for Children’ in David Almond’s Skellig Soňa Šnircová Chapter Two ............................................................................................. -

Slow Expansion. Neomodernism As a Postnational Tendency in Contemporary Cinema

TRANSMISSIONS: THE JOURNAL OF FILM AND MEDIA STUDIES 2016, VOL.1, NO. 2, PP. 100-117. Miłosz Stelmach Jagiellonian University Slow Expansion. Neomodernism as a Postnational Tendency in Contemporary Cinema Abstract The article presents a theoretical overview of a distinctive strand of contemporary cinema identified in the text as neomodernism (as defined by Rafał Syska). It focuses on works of filmmakers such as Béla Tarr, Aleksander Sokurov or Tsai Ming-liang and their followers and tries to present them as a part of informal postnational artistic movement developing in cinema from mid-90s onward. The aim of the article is to examine critically the journalistic and reductive category of slow cinema usually applied to auteurs mentioned above and propose term more burdened with cultural connotations and thus open for nuanced historical and theoretical studies. The particular attention is given to the international character of neomodernism that negates the traditional boundaries of national schools as well as the division of centre-periphery in world cinema shaped by the first wave of postwar modernist cinema. Neomodernism rather moves the notion of centre to the institutional level with the growing importance of festivals, film agents and public fund that take the place of production companies as the main actors in the transnational net of art-house cinema circulation. Key words: contemporary cinema, modernism, slow cinema, postnational cinema, neomodernism Introduction Over the course of the last two decades, the debate over cinema and modernism has taken the form of a dialectical struggle since two distinctive theoretical standpoints emerged, of which the more traditional and still dominant is rooted in art history and literary studies of the post-war years. -

African Modernism and Identity Politics: Curatorial Practice in the Global South with Particular Reference to South Africa

AFRICAN MODERNISM AND IDENTITY POLITICS: CURATORIAL PRACTICE IN THE GLOBAL SOUTH WITH PARTICULAR REFERENCE TO SOUTH AFRICA by Jayne Kelly Crawshay-Hall 27367496 A mini-dissertation submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree Magister Artium (Fine Arts) (Option three: curatorial practice) in the DEPARTMENT OF VISUAL ARTS at the UNIVERSITY OF PRETORIA FACULTY OF HUMANITIES Supervisor: Professor Elfriede Dreyer April 2013 © University of Pretoria ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS My study began with a burning desire to better understand identity in contemporary South African society. I would like to express my deepest gratitude to Professor Elfriede Dreyer, my research supervisor and mentor, for her continual support, guidance and encouragement, both in an academic and professional manner. Your enthusiasm and critical guidance provided me with an awareness and determination beyond merely the academic scope of this study, thank you. I wish to thank The University of Pretoria for awarding me with an academic bursary, for which I am indebted to them, and for providing the support and recognition for this study. I would also like to thank the staff at the Visual Arts Department for the encouragement in my studies. My deepest appreciation is extended to Dr. Paul Bayliss, curator of the Absa Gallery, Johannesburg, for his endless support in realising the curatorial project. I would like to extend my thanks to the organisers at the Absa Gallery, and the Absa corporation for their support within this project. Furthermore, my deepest thanks need go to all the artists who have been involved in this study and who, through their art, have shared a life journey with me, and continue to inspire me. -

Existentialism in Metamodern Art

EXISTENTIALISM IN METAMODERN ART EXISTENTIALISM IN METAMODERN ART: THE OTHER SIDE OF OSCILLATION By STEPHEN DANILOVICH, B.A. A Thesis Submitted to the School of Graduate Studies in Partial Fulfilment of the Requirements for the Degree Master of Arts McMaster University © Copyright by Stephen Danilovich, August 2018 McMaster University MASTER OF ARTS (2018) Hamilton, Ontario (English) TITLE: Existentialism in Metamodern Art: The Other Side of Oscillation AUTHOR: Stephen Danilovich, B.A. (McMaster University) SUPERVISOR: Professor Jeffery Donaldson NUMBER OF PAGES: 91 ii LAY ABSTRACT There is a growing consensus among scholars that early 21st century art can no longer be explained in terms of familiar aesthetic conventions. The term ‘metamodernism’ is catching on as a description of our new era. Metamodernism is understood as an oscillation between two modalities – modernism and postmodernism – generating art that is more idealistic and romantic than what we have seen in previous decades, while retaining its capacity to be ironizing and self-aware. However, the discourse surrounding metamodernism has been tentative, provisional, and difficult to circumscribe. In avoiding any overarching claims or settled positions, metamodernism risks remaining only a radicalisation of previous conventions rather than a genuine evolution. The goal of this project is to come to grips with the core tenets of metamodernism, to present them more clearly and distinctly, and to suggest what the scholarship surrounding metamodernism might need to move beyond its current constraints. iii ABSTRACT The discourse surrounding art in the early 21st century seeks to explain our artistic practices in terms of a radically distinct set of conventions, which many have dubbed ‘metamodern.’ Metamodernism abides neither by modernist aspirations of linear progress, nor by the cynical distrust of narratives familiar to postmodernism. -

The Planetary Turn

The Planetary Turn The Planetary Turn Relationality and Geoaesthetics in the Twenty- First Century Edited by Amy J. Elias and Christian Moraru northwestern university press evanston, illinois Northwestern University Press www .nupress.northwestern .edu Copyright © 2015 by Northwestern University Press. Published 2015. All rights reserved. Printed in the United States of America 10 9 8 7 6 5 4 3 2 1 Library of Congress Cataloging- in- Publication Data The planetary turn : relationality and geoaesthetics in the twenty-first century / edited by Amy J. Elias and Christian Moraru. pages cm Includes bibliographical references. ISBN 978-0-8101-3073-9 (cloth : alk. paper) — ISBN 978-0-8101-3075-3 (pbk. : alk. paper) — ISBN 978-0-8101-3074-6 (ebook) 1. Space and time in literature. 2. Space and time in motion pictures. 3. Globalization in literature. 4. Aesthetics. I. Elias, Amy J., 1961– editor of compilation. II. Moraru, Christian, editor of compilation. PN56.S667P57 2015 809.9338—dc23 2014042757 Except where otherwise noted, this book is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License. To view a copy of this license, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/. In all cases attribution should include the following information: Elias, Amy J., and Christian Moraru. The Planetary Turn: Relationality and Geoaesthetics in the Twenty-First Century. Evanston: Northwestern University Press, 2015. The following material is excluded from the license: Illustrations and an earlier version of “Gilgamesh’s Planetary Turns” by Wai Chee Dimock as outlined in the acknowledgments. For permissions beyond the scope of this license, visit http://www.nupress .northwestern.edu/. -

New Sincerity in American Literature

University of Rhode Island DigitalCommons@URI Open Access Dissertations 2018 THE NEW SINCERITY IN AMERICAN LITERATURE Matthew J. Balliro University of Rhode Island, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.uri.edu/oa_diss Recommended Citation Balliro, Matthew J., "THE NEW SINCERITY IN AMERICAN LITERATURE" (2018). Open Access Dissertations. Paper 771. https://digitalcommons.uri.edu/oa_diss/771 This Dissertation is brought to you for free and open access by DigitalCommons@URI. It has been accepted for inclusion in Open Access Dissertations by an authorized administrator of DigitalCommons@URI. For more information, please contact [email protected]. THE NEW SINCERITY IN AMERICAN LITERATURE BY MATTHEW J. BALLIRO A DISSERTATION SUBMITTED IN PARTIAL FULFILLMENT OF THE REQUIREMENTS FOR THE DEGREE OF DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY IN ENGLISH UNIVERSITY OF RHODE ISLAND 2018 DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY DISSERTATION OF Matthew J. Billaro APPROVED: Dissertation Committee: Major Professor Naomi Mandel Ryan Trimm Robert Widdell Nasser H. Zawia DEAN OF THE GRADUATE SCHOOL UNIVERSITY OF RHODE ISLAND 2018 Abstract The New Sincerity is a provocative mode of literary interpretation that focuses intensely on coherent connections that texts can build with readers who are primed to seek out narratives and literary works that rest on clear and stable relationships between dialectics of interior/exterior, self/others, and meaning/expression. Studies on The New Sincerity so far have focused on how it should be situated against dominant literary movements such as postmodernism. My dissertation aims for a more positive definition, unfolding the most essential details of The New Sincerity in three parts: by exploring the intellectual history of the term “sincerity” and related ideas (such as authenticity); by establishing the historical context that created the conditions that led to The New Sincerity’s genesis in the 1990s; and by tracing the different forms reading with The New Sincerity can take by analyzing a diverse body of literary texts. -

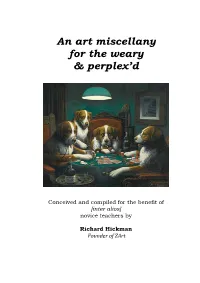

An Art Miscellany for the Weary & Perplex'd. Corsham

An art miscellany for the weary & perplex’d Conceived and compiled for the benefit of [inter alios] novice teachers by Richard Hickman Founder of ZArt ii For Anastasia, Alexi.... and Max Cover: Poker Game Oil on canvas 61cm X 86cm Cassius Marcellus Coolidge (1894) Retrieved from Wikimedia Commons [http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-sa/3.0/] Frontispiece: (My Shirt is Alive With) Several Clambering Doggies of Inappropriate Hue. Acrylic on board 60cm X 90cm Richard Hickman (1994) [From the collection of Susan Hickman Pinder] iii An art miscellany for the weary & perplex’d First published by NSEAD [www.nsead.org] ISBN: 978-0-904684-34-6 This edition published by Barking Publications, Midsummer Common, Cambridge. © Richard Hickman 2018 iv Contents Acknowledgements vi Preface vii Part I: Hickman's Art Miscellany Introductory notes on the nature of art 1 DAMP HEMs 3 Notes on some styles of western art 8 Glossary of art-related terms 22 Money issues 45 Miscellaneous art facts 48 Looking at art objects 53 Studio techniques, materials and media 55 Hints for the traveller 65 Colours, countries, cultures and contexts 67 Colours used by artists 75 Art movements and periods 91 Recent art movements 94 World cultures having distinctive art forms 96 List of metaphorical and descriptive words 106 Part II: Art, creativity, & education: a canine perspective Introductory remarks 114 The nature of art 112 Creativity (1) 117 Art and the arts 134 Education Issues pertaining to classification 140 Creativity (2) 144 Culture 149 Selected aphorisms from Max 'the visionary' dog 156 Part III: Concluding observations The tail end 157 Bibliography 159 Appendix I 164 v Illustrations Cover: Poker Game, Cassius Coolidge (1894) Frontispiece: (My Shirt is Alive With) Several Clambering Doggies of Inappropriate Hue, Richard Hickman (1994) ii The Haywain, John Constable (1821) 3 Vagveg, Tabitha Millett (2013) 5 Series 1, No. -

Art 5307 Contemporary Art History Professor Carol H. Fairlie

Art 5307 Contemporary Art History Professor Carol H. Fairlie OFFICE: 09--Fine Arts Building OFFICE HOURS: By appointment CELL PHOVE 432-294-1313 OFFICE PHONE: 837-8258 Email: [email protected] Office Hours Available by text 432-294-1313 after 10 am until midnight. I am in the classroom usually 1-2 pm. POST COVID COURSE INFO If you are not feeling well, please do the work which will be on-line. Due to the impact of the virus, if you have not received a vaccine, your mask must be worn at all times, and social separation of 6 feet must be maintained. Failure to do this will result in you being asked to leave the classroom REQUIRED TEXT : Try interlibrary loans, digital or used copies. The Western Humanities, sixth edition by Roy T. Matthews and F. Dewitt Platt (2008-08-01) Art Today: Edward Lucie Smith ISBN-10- 0714818062 Themes of Contemporary Art after 1980: Jean Robertson isbn-10: 0190276622 After Modern Art: 1945-2017 (Oxford History of Art) 2nd Edition: David Hopkins ISBN-10 : 0199218455 OBJECTIVE: To fully cover the concepts and movements of Art in the last twenty years, one must have a firm understanding of History for the past 100 years. The class will be required to do a lot of reading, note taking research and analysis. The textbooks and DVD’s will be relied upon to give us a basis about the class. Aesthetics, art history, exhibitions, artists, and art criticism will be relied upon to conduct the last few days of the class. The emphasis of the class will be to look at Art of the 1980's through the Present. -

Le Cinéma Remoderniste Histoire Et Théorie D'une Esthétique Contemporaine

UNIVERSITÉ SORBONNE NOUVELLE – PARIS III Mémoire final de Master 2 Mention : Études cinématographiques et audiovisuelles Spécialité : Recherche Titre : LE CINÉMA REMODERNISTE HISTOIRE ET THÉORIE D'UNE ESTHÉTIQUE CONTEMPORAINE Auteur : Florian MARICOURT n° 21207254 Mémoire final dirigé par Nicole BRENEZ Soutenu à la session de juin 2014 LE CINÉMA REMODERNISTE HISTOIRE ET THÉORIE D'UNE ESTHÉTIQUE CONTEMPORAINE Florian Maricourt Illustration de couverture : Photogramme extrait de Notre espoir est inconsolable (Florian Maricourt, 2013) Une chanson que braille une fille en brossant l'escalier me bouleverse plus qu'une savante cantate. Chacun son goût. J'aime le peu. J'aime aussi l'embryonnaire, le mal façonné, l'imparfait, le mêlé. J'aime mieux les diamants bruts, dans leur gangue. Et avec crapauds. Jean Dubuffet Prospectus et tous écrits suivants, 1951 En ces temps d'énormité, de films à grand spectacle, de productions à cent millions de dollars, je veux prendre la parole en faveur du petit, des actes invisibles de l’esprit humain, si subtils, si petits qu’ils meurent dès qu’on les place sous les sunlights. Je veux célébrer les petites formes cinématographiques, les formes lyriques, les poèmes, les aquarelles, les études, les esquisses, les cartes postales, les arabesques, les triolets, les bagatelles et les petits chants en 8mm. Jonas Mekas Manifeste contre le centenaire du cinéma, 1996 i am a desperate man who will not bow down to acolayed or success i am a desperate man who loves the simplisity of painting and hates gallarys and white walls and the dealers in art who loves unreasonableness and hot headedness who loves contradiction hates publishing houses and also i am vincent van gough Billy Childish I am the Strange Hero of Hunger, 2005 Je tiens à remercier chaleureusement les cinéastes remodernistes qui ont aimablement répondu à mes questions, en particulier Scott Barley, Heidi Elise Beaver, Dean Kavanagh, Rouzbeh Rashidi, Roy Rezaäli, Jesse Richards et Peter Rinaldi. -

After Postmodernism: Ethical Paradigms in Contemporary

After Postmodernism: Ethical Paradigms in Contemporary American Fiction Inaugural-Dissertation zur Erlangung des Doktorgrades der Philosophie an der Ludwig-Maximilians-Universität München vorgelegt von Andrew Frederick Allen aus Torrance, CA USA 2021 Referent/in: Prof. Dr. Klaus Benesch Korreferent/in: Prof. Dr. Raoul Eshelman Tag der mündlichen Prüfung: 17.07.2018 Allen 1 Table of Contents Introduction 3 1 After Postmodernism 14 1.1 Introduction 14 1.2 Theories Extending Postmodernism 14 1.2.1 Altermodernism 14 1.2.2 Metamodernism 20 1.2.3 Post-postmodernism 25 1.2.4 Cosmodernism 33 1.3 Theories Deviating from Postmodernism 38 1.3.1 Hypermodernism 38 1.3.2 Performatism 46 1.3.3 Digimodernism 53 1.4 The Importance of Ethics 61 2 Postmodern Ethics and the Ethical Dominant 65 2.1 Introduction 65 2.2 Postmodern Ethics and its Discontents 65 2.3 An Ethical Dominant? 74 2.4 Conclusion 77 3 The Period After Postmodernism 78 3.1 A New World Order 78 3.1.1 The End of Postmodernity 78 3.1.2 A New Modernity 83 3.1.3 The Death of Privilege 85 Allen 2 3.1.4 An Ethical Gap 88 3.2 Signs of Postmodernism's Passing: Three Ethical Paradigms 90 3.2.1 The Virtue of Selfishness 90 3.2.2 A Higher Power 92 3.2.3 The Ecological Metanarrative 98 3.3 Conclusion 100 4 The Virtue of Selfishness 101 4.1 Introduction 101 4.2 Two Girls, Fat and Thin by Mary Gaitskill 106 4.3 Big If by Mark Costello 128 5. -

Tom Mccarthy and Metamodernism, an Uneasy Dialogue

TOM MCCARTHY AND METAMODERNISM, AN UNEASY DIALOGUE. AN ANALYSIS OF THE NOVEL C AND ITS RELATION TO THE METAMODERN FRAMEWORK. Rodolfo Alpizar Carracedo Stamnummer: 015002362 Promotor: Prof. dr. Birgit Van Puymbroeck Masterproef voorgelegd voor het behalen van de graad master in de Taal- en Letterkunde: Engels Academiejaar: 2016 - 2017 Acknowledgements ‘No man is an island’1 is the first thing that comes to mind when looking at the completed form of this dissertation. As I wait for Alexandra to finish her relentless proofreading of my final draft, I think of all the people and conditions that allowed for this moment to happen. In what now seems like a decade ago, I was lucky to have a conversation with dr. Birgit van Puymbroeck where the idea to write a dissertation about Tom McCarthy’s work was born. I was interested in those places where literature and philosophy meet, and dr. Van Puymbroeck came up with the suggestion of working with this contemporary enfant terrible. His novel C has all the ingredients of what I was looking for: commitment, challenge, wit and mischief. However, I must admit that in diving into the world that lies under its pages, I would feel at moments like Alice falling down a rabbit hole of infinite doors, with mixture of excitement and anxiety. I must express my deepest gratitude to my promotor dr. Van Puymbroeck for her constant encouragement, and for steadily guiding my research along its many turns. Only a strongly supportive network of family and friends have kept me from losing all traces of sanity along this road. -

It's All in the Family—Metamodernism and the Contemporary (Anglo-)

It’s All In the Family—Metamodernism and the Contemporary (Anglo-) ―American‖ Novel A Dissertation submitted by Terence DeToy in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in English. Tufts University August 2015 Advisor: Ichiro Takayoshi ii Abstract This dissertation examines the function of family as a thematic in the contemporary Anglo- American novel. It argues that contemporary aesthetics increasingly presents the family as an enabling platform for conciliation with the social totality: as a space of personal development, readying one for life in the wider social field. This analyses hinges on readings of Jonathan Franzen‘s Freedom (2010), Zadie Smith‘s NW (2012), A. M. Homes‘ May We Be Forgiven (2012) and Caryl Phillips‘ In the Falling Snow. In approaching these novels, this project addresses the theoretical lacuna left open by the much-touted retreat of postmodernism as a general cultural-aesthetic strategy. This project identifies these novels as examples of a new and competing ideological constellation: metamodernism. Metamodernism encompasses the widely cited return of sincerity to contemporary aesthetics, though this project explains this development in a novel way: as a cultural expression from within the wider arc of postmodernism itself. One recurrent supposition within this project is that postmodernism, in its seeming nihilism, betrays a thwarted political commitment; on the other hand contemporary metamodern attitudes display the seriousness and earnestness of political causes carried out to an ironic disregard of the political. Metamodernism, in other words, is not a wholesale disavowal of postmodern irony, but a re-arrangement of its function: a move from sincere irony to an ironic sincerity.