After Postmodernism: Ethical Paradigms in Contemporary

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Reactionary Postmodernism? Neoliberalism, Multiculturalism, the Internet, and the Ideology of the New Far Right in Germany

University of Vermont ScholarWorks @ UVM UVM Honors College Senior Theses Undergraduate Theses 2018 Reactionary Postmodernism? Neoliberalism, Multiculturalism, the Internet, and the Ideology of the New Far Right in Germany William Peter Fitz University of Vermont Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarworks.uvm.edu/hcoltheses Recommended Citation Fitz, William Peter, "Reactionary Postmodernism? Neoliberalism, Multiculturalism, the Internet, and the Ideology of the New Far Right in Germany" (2018). UVM Honors College Senior Theses. 275. https://scholarworks.uvm.edu/hcoltheses/275 This Honors College Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by the Undergraduate Theses at ScholarWorks @ UVM. It has been accepted for inclusion in UVM Honors College Senior Theses by an authorized administrator of ScholarWorks @ UVM. For more information, please contact [email protected]. REACTIONARY POSTMODERNISM? NEOLIBERALISM, MULTICULTURALISM, THE INTERNET, AND THE IDEOLOGY OF THE NEW FAR RIGHT IN GERMANY A Thesis Presented by William Peter Fitz to The Faculty of the College of Arts and Sciences of The University of Vermont In Partial Fulfilment of the Requirements For the Degree of Bachelor of Arts In European Studies with Honors December 2018 Defense Date: December 4th, 2018 Thesis Committee: Alan E. Steinweis, Ph.D., Advisor Susanna Schrafstetter, Ph.D., Chairperson Adriana Borra, M.A. Table of Contents Introduction 1 Chapter One: Neoliberalism and Xenophobia 17 Chapter Two: Multiculturalism and Cultural Identity 52 Chapter Three: The Philosophy of the New Right 84 Chapter Four: The Internet and Meme Warfare 116 Conclusion 149 Bibliography 166 1 “Perhaps one will view the rise of the Alternative for Germany in the foreseeable future as inevitable, as a portent for major changes, one that is as necessary as it was predictable. -

Songs by Artist

Reil Entertainment Songs by Artist Karaoke by Artist Title Title &, Caitlin Will 12 Gauge Address In The Stars Dunkie Butt 10 Cc 12 Stones Donna We Are One Dreadlock Holiday 19 Somethin' Im Mandy Fly Me Mark Wills I'm Not In Love 1910 Fruitgum Co Rubber Bullets 1, 2, 3 Redlight Things We Do For Love Simon Says Wall Street Shuffle 1910 Fruitgum Co. 10 Years 1,2,3 Redlight Through The Iris Simon Says Wasteland 1975 10, 000 Maniacs Chocolate These Are The Days City 10,000 Maniacs Love Me Because Of The Night Sex... Because The Night Sex.... More Than This Sound These Are The Days The Sound Trouble Me UGH! 10,000 Maniacs Wvocal 1975, The Because The Night Chocolate 100 Proof Aged In Soul Sex Somebody's Been Sleeping The City 10Cc 1Barenaked Ladies Dreadlock Holiday Be My Yoko Ono I'm Not In Love Brian Wilson (2000 Version) We Do For Love Call And Answer 11) Enid OS Get In Line (Duet Version) 112 Get In Line (Solo Version) Come See Me It's All Been Done Cupid Jane Dance With Me Never Is Enough It's Over Now Old Apartment, The Only You One Week Peaches & Cream Shoe Box Peaches And Cream Straw Hat U Already Know What A Good Boy Song List Generator® Printed 11/21/2017 Page 1 of 486 Licensed to Greg Reil Reil Entertainment Songs by Artist Karaoke by Artist Title Title 1Barenaked Ladies 20 Fingers When I Fall Short Dick Man 1Beatles, The 2AM Club Come Together Not Your Boyfriend Day Tripper 2Pac Good Day Sunshine California Love (Original Version) Help! 3 Degrees I Saw Her Standing There When Will I See You Again Love Me Do Woman In Love Nowhere Man 3 Dog Night P.S. -

New Modernism(S)

New Modernism(s) BEN DUVALL 5 Intro: Surfaces and Signs 13 The Typography of Utopia/Dystopia 27 The Hyperlinked Sign 41 The Aesthetics of Refusal 5 Intro: Surfaces and Signs What can be said about graphic design, about the man- ner in which its artifact exists? We know that graphic design is a manipulation of certain elements in order to communicate, specifically typography and image, but in order to be brought together, these elements must exist on the same plane–the surface. If, as semi- oticians have said, typography and images are signs in and of themselves, then the surface is the locus for the application of sign systems. Based on this, we arrive at a simple equation: surface + sign = a work of graphic design. As students and practitioners of this kind of “surface curation,” the way these elements are functioning currently should be of great interest to us. Can we say that they are operating in fundamentally different ways from the way they did under modern- ism? Even differently than under postmodernism? Per- haps the way the surface and sign are treated is what distinguishes these cultural epochs from one another. We are confronted with what Roland Barthes de- fined as a Text, a site of interacting and open signs, 6 NEW MODERNISM(S) and therefore, a site of reader interpretation and of SIGNIFIER + SIGNIFIED = SIGN semiotic play.1 This is of utmost importance, the treat- ment of the signs within a Text is how we interpret, Physical form of an Ideas represented Unit of meaning idea, e.g. -

Theorizing Political Psychology: Doing Integrative Social Science Under the Condition of Postmodernity

Theorizing political psychology: Doing integrative social science under the condition of postmodernity Journal of the Theory of Social Behaviour, (2003), pp. 427- 460 Shawn W Rosenberg Graduate Program in Political Psychology School of Social Sciences University of California, Irvine Email: [email protected] Telephone: (949) 824-7143 ABSTRACT At the beginning of the 21st century, the field of political psychology; like the social sciences more generally, is being challenged. New theoretical direction is being demanded from within and a greater epistemological sophistication and ethical relevance is being demanded from without. In response, direction for a reconstructed political psychology is offered here. To begin, a theoretical framework for a truly integrative political psychology is sketched. This is done in light of the apparent limits of cross-disciplinary or multidisciplinary inquiry. In the attempt to transcend these limits, the theoretical approach offered directly addresses the dually structured quality of social life as the singular product of both organizing social structures and defining discourse communities on the one hand and motivated, thinking individuals on the other. To further this theoretical effort, meta-theoretical considerations are addressed. The modernist- postmodernist debate regarding the status of truth and value is used as a point of departure for constructing the epistemological foundation for a truly political psychology. In this light, structural pragmatic guidelines for theory construction, empirical research and normative inquiry are presented. Political psychology, along with the rest of the social sciences, is at a crossroads. In part, this is an internal matter - the result of the exhaustion of existing paradigms. The product of psychological or sociological theorizing of the early and mid 20th century, these paradigms have oriented political psychological research for most of the last fifty years. -

Connections Between Gilles Lipovetsky's Hypermodern Times and Post-Soviet Russian Cinema James M

Communication and Theater Association of Minnesota Journal Volume 36 Article 2 January 2009 "Brother," Enjoy Your Hypermodernity! Connections between Gilles Lipovetsky's Hypermodern Times and Post-Soviet Russian Cinema James M. Brandon Hillsdale College, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://cornerstone.lib.mnsu.edu/ctamj Part of the Film and Media Studies Commons, and the Soviet and Post-Soviet Studies Commons Recommended Citation Brandon, J. (2009). "Brother," Enjoy Your Hypermodernity! Connections between Gilles Lipovetsky's Hypermodern Times and Post- Soviet Russian Cinema. Communication and Theater Association of Minnesota Journal, 36, 7-22. This General Interest is brought to you for free and open access by Cornerstone: A Collection of Scholarly and Creative Works for Minnesota State University, Mankato. It has been accepted for inclusion in Communication and Theater Association of Minnesota Journal by an authorized editor of Cornerstone: A Collection of Scholarly and Creative Works for Minnesota State University, Mankato. Brandon: "Brother," Enjoy Your Hypermodernity! Connections between Gilles CTAMJ Summer 2009 7 “Brother,” Enjoy your Hypermodernity! Connections between Gilles Lipovetsky’s Hypermodern Times and Post-Soviet Russian Cinema James M. Brandon Associate Professor [email protected] Department of Theatre and Speech Hillsdale College Hillsdale, MI ABSTRACT In prominent French social philosopher Gilles Lipovetsky’s Hypermodern Times (2005), the author asserts that the world has entered the period of hypermodernity, a time where the primary concepts of modernity are taken to their extreme conclusions. The conditions Lipovetsky described were already manifesting in a number of post-Soviet Russian films. In the tradition of Slavoj Zizek’s Enjoy Your Symptom (1992), this essay utilizes a number of post-Soviet Russian films to explicate Lipovetsky’s philosophy, while also using Lipovetsky’s ideas to explicate the films. -

Metamodern Writing in the Novel by Thomas Pynchon

INTERLITT ERA RIA 2019, 24/2: 495–508 495 Bleeding Edge of Postmodernism Bleeding Edge of Postmoder nism: Metamodern Writing in the Novel by Thomas Pynchon SIMON RADCHENKO Abstract. Many different models of co ntemporary novel’s description arose from the search for methods and approaches of post-postmodern texts analysis. One of them is the concept of metamodernism, proposed by Timotheus Vermeulen and Robin van den Akker and based on the culture and philosophy changes at the turn of this century. This article argues that the ideas of metamodernism and its main trends can be successfully used for the study of contemporary literature. The basic trends of metamodernism were determined and observed through the prism of literature studies. They were implemented in the analysis of Thomas Pynchon’s latest novel, Bleeding Edge (2013). Despite Pynchon being usually considered as postmodern writer, the use of metamodern categories for describing his narrative strategies confirms the idea of the novel’s post-postmodern orientation. The article makes an endeavor to use metamodern categories as a tool for post-postmodern text studies, in order to analyze and interpret Bleeding Edge through those categories. Keywords: meta-modernism; postmodernism; Thomas Pynchon; oscillation; new sincerity How can we study something that has not been completely described yet? Although discussions of a paradigm shift have been around long enough, when talking about contemporary literary phenomena we are still using the categories of feeling rather than specific instruments. Perception of contemporary lit era- ture as post-postmodern seems dated today. However, Joseph Tabbi has questioned the novelty of post-postmodernism as something new, different from postmodernism and proposes to consider the abolition of irony and post- modernism (Tabbi 2017). -

The Dialectic of Freedom 1St Edition Pdf Free Download

THE DIALECTIC OF FREEDOM 1ST EDITION PDF, EPUB, EBOOK Maxine Greene | 9780807728970 | | | | | The Dialectic of Freedom 1st edition PDF Book She examines the ways in which the disenfranchised have historically understood and acted on their freedom—or lack of it—in dealing with perceived and real obstacles to expression and empowerment. It offers readers a critical opportunity to reflect on our continuing ideological struggles by examining popular books that have made a difference in educational discourse. Professors: Request an Exam Copy. Major works. Max Horkheimer Theodor W. The latter democratically makes everyone equally into listeners, in order to expose them in authoritarian fashion to the same programs put out by different stations. American Paradox American Quest. Instead the conscious decision of the managing directors executes as results which are more obligatory than the blindest price-mechanisms the old law of value and hence the destiny of capitalism. Forgot your password? There have been two English translations: the first by John Cumming New York: Herder and Herder , ; and a more recent translation, based on the definitive text from Horkheimer's collected works, by Edmund Jephcott Stanford: Stanford University Press, Learn how to enable JavaScript on your browser. Peter Lang. The truth that they are nothing but business is used as an ideology to legitimize the trash they intentionally produce. Archetypal literary criticism New historicism Technocriticism. The author concludes with suggestions for approaches to teaching and learning that can provoke both educators and students to take initiatives, to transcend limits, and to pursue freedom—not in solitude, but in reciprocity with others, not in privacy, but in a public space. -

A Critical Concept of Injustice. Trichotomy Critique, Explanation, and Normativity

http://dx.doi.org/10.5007/1677-2954.2014v13n1p50 A CRITICAL CONCEPT OF INJUSTICE. TRICHOTOMY CRITIQUE, EXPLANATION, AND NORMATIVITY UM CONCEITO CRÍTICO DE INJUSTIÇA. A TRICOTOMIA CRÍTICA, ESCLARECIMENTO E NORMATIVIDADE MAREK HRUBEC1 (Charles University, Czech Republic) ABSTRACT The article deals with an issue of a critical concept of injustice. It concentrates on injustice by focusing on three fundamental elements of Critical theory of society: critique, explanation, and normativity. Firstly, it clarifies the need for critical social criticism to have an internal character. Secondly, it concentrates on relations between individual elements of the above-mentioned trichotomy, and stresses the consequences of such an analysis for a Critical social theory. It shows that only an articulation of all three elements in their mutual constitutive relations will enable to work out a critical concept of in/justice. Keywords: Injustice. Justice. Critical Theory. Critique. Explanation. Normativity. A theory of justice requires a critical concept of injustice2. I will articulate such a concept from the point of view of Critical Theory of Society. I will analyze three fundamental elements of Critical Theory – critique, explanation and normativity – which can be identified already in the initial programmatic documents of the founders of Critical Theory (the Frankfurt School), and consequently mapped in texts of their followers up until today. Although these elements have been present in Critical Theory since its beginning, and their existence was an implicit precondition for Critical Theory, they have been articulated only vaguely in their complex mutual relations. This is because only some of these elements have as a rule been addressed, and because just a few of the relations between them have been discussed. -

Sarajevo 1967 ° "' 1 '"

Grondmaster ayme, lefl, explafntnq the qallle 01 d»eu to 80"011, c.nter, and USSR Champion Stein, Byrne later floated SteIn 10 anOfher leuon o"er the board. accountmq tor Sleln's only lou 01 lhe lournamenl, SARAJEVO 1967 I 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 A 10 11 12 13 14 15 16 W L D !: ~~::: :::::::::::::::::::::.:.... .::: :' .' ...: . ~ ~~, ---.-~;.-.::~;--:~;-"~,==~: =~~f. =~"tl =j~~=;~t="ii"'\'----;.~:;:--;"-;-·I - ::- -;:===-;~'----;~'---";:""~=- 10 ~ .4- ~ 3. tknko , If.! Y.i: % 0 I 0 1 1 I ~ I \ _ ;-1 _~'~ ,;--;;-, - \1)-5 x 1h 'h ':-l - '--'' 1 I I 1 'h I 0 I ,';-,,'c-- -:';-_-- 1().5_ °1 '""' 1h x 0 0 n 1 n I ¥, I 1 1 I ,..' .....;:3_ ~ 9Ik.5 ~ h 1 x I,i h ~ 1 n h I I,i 1;.--:1_ _ 5 1 9 9h . ~~ ° "1 h 1 I,i x 0 I 'h 0 1 "':"''-''''7----:-1 t 6" 5'- - 8'7 .6% o o lit liz 1 x 1,1: .., .., 1 "':t I t ¥l -.' , 2 ~ 81.1 f1lh 1 0 0 n 0 If. :< 0 0 1 J I n _ -;-I _ ';--;-6_ ,_ _ ,.. - 11 Duc1n tcin .. .. .... ... n ~ ~ ~ ~ : ~ "~'- : : ~ ~ ~ --,~,,-:~:-~ ----.-~ :: ~! 12. Ja.noS('vic .... ... ... ... .. ~_-;";... _~ ~ _Ifl "1 ;;:0'--;,;..0 _ 0,,-:"':-"''7--;;:''--''''' 1 ~"''-.;.I _ _.;:-' _ ;!i 8 f.. 9 13. Pict%.Sch ................................... \o!t Vr 'tit;. _ ";. ,-~O:- 0 n 'fl 0 0 . __1 'h x 0 1:'.1 0 1 6 --;8- - - 5- 10 14. Bogdanuvic .. .................. Y.t 0 0 0 0 lit Yt 0 0 Yt 1 0 I x 0 h 2 8 5 _ _ " "1.100" :~ : ~:~;:~. -

Table of Contents

Table of Contents 0. Introduction..................................................................................................... 4 1. Terminological issues ...................................................................................... 6 2. Placement of David Foster Wallace ................................................................. 8 2.1 Critical literature on David Foster Wallace .................................................. 9 2.2 Starting point and purpose of this thesis ................................................. 11 3. General aspects of the postmodern era, epistemology ................................. 13 4. Literary postmodernism ................................................................................. 16 4.1 Philosophical orientation, complication of authorship ............................... 16 4.2 Foregrounding structure, breaking the narrative illusion .......................... 19 4.3 Pastiche, parody ....................................................................................... 20 4.4 Disjunction, interruption, fragmentation .................................................. 21 4.5 Temporality and temporal disorder .......................................................... 25 5. Post-postmodernisms .................................................................................... 26 5.1 Performatism ............................................................................................ 27 5.2 Digimodernism ........................................................................................ -

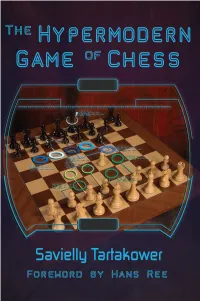

Hypermodern Game of Chess the Hypermodern Game of Chess

The Hypermodern Game of Chess The Hypermodern Game of Chess by Savielly Tartakower Foreword by Hans Ree 2015 Russell Enterprises, Inc. Milford, CT USA 1 The Hypermodern Game of Chess The Hypermodern Game of Chess by Savielly Tartakower © Copyright 2015 Jared Becker ISBN: 978-1-941270-30-1 All Rights Reserved No part of this book maybe used, reproduced, stored in a retrieval system or transmitted in any manner or form whatsoever or by any means, electronic, electrostatic, magnetic tape, photocopying, recording or otherwise, without the express written permission from the publisher except in the case of brief quotations embodied in critical articles or reviews. Published by: Russell Enterprises, Inc. PO Box 3131 Milford, CT 06460 USA http://www.russell-enterprises.com [email protected] Translated from the German by Jared Becker Editorial Consultant Hannes Langrock Cover design by Janel Norris Printed in the United States of America 2 The Hypermodern Game of Chess Table of Contents Foreword by Hans Ree 5 From the Translator 7 Introduction 8 The Three Phases of A Game 10 Alekhine’s Defense 11 Part I – Open Games Spanish Torture 28 Spanish 35 José Raúl Capablanca 39 The Accumulation of Small Advantages 41 Emanuel Lasker 43 The Canticle of the Combination 52 Spanish with 5...Nxe4 56 Dr. Siegbert Tarrasch and Géza Maróczy as Hypermodernists 65 What constitutes a mistake? 76 Spanish Exchange Variation 80 Steinitz Defense 82 The Doctrine of Weaknesses 90 Spanish Three and Four Knights’ Game 95 A Victory of Methodology 95 Efim Bogoljubow -

Postmillennial Trends in Anglophone Literatures, Cultures and Media

Postmillennial Trends in Anglophone Literatures, Cultures and Media Postmillennial Trends in Anglophone Literatures, Cultures and Media Edited by Soňa Šnircová and Slávka Tomaščíková Postmillennial Trends in Anglophone Literatures, Cultures and Media Edited by Soňa Šnircová and Slávka Tomaščíková This book first published 2019 Cambridge Scholars Publishing Lady Stephenson Library, Newcastle upon Tyne, NE6 2PA, UK British Library Cataloguing in Publication Data A catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library Copyright © 2019 by Soňa Šnircová, Slávka Tomaščíková and contributors All rights for this book reserved. No part of this book may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted, in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording or otherwise, without the prior permission of the copyright owner. ISBN (10): 1-5275-2709-3 ISBN (13): 978-1-5275-2709-6 TABLE OF CONTENTS Introduction ................................................................................................. 1 Postmillennial Trends in Anglophone Literatures, Cultures and Media Soňa Šnircová and Slávka Tomaščíková Part I: Addressing the Theories of a New Cultural Paradigm Chapter One ............................................................................................... 16 Metamodernism for Children?: A Performatist Rewriting of Gabriel García Márquez’s ‘A Very Old Man With Enormous Wings: A Tale for Children’ in David Almond’s Skellig Soňa Šnircová Chapter Two .............................................................................................