UNIVERSITY of CALIFORNIA, SAN DIEGO The

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Introduction

Notes Introduction 1 The principal works were Benny Morris, The Birth of the Palestinian Refugee Problem (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1987); Ilan Pappé, Britain and the Arab-Israeli Conflict, 1948–1951 (Basingstoke: Macmillan in associa- tion with St. Antony’s College Oxford, 1988); Avi Shlaim, Collusion Across the Jordan: King Abdullah, the Zionist Movement and the Partition of Palestine (Oxford: Clarendon, 1988). 2 On the origins of this myth, see pp. 85–87. 3 In particular, see Barbara Tuchman, The Bible and the Sword: England and Palestine from the Bronze Age to Balfour (New York: New York University Press, 1956), pp. xiv, 311–312, 337; Franz Kobler, The Vision was There: A History of the British Movement for the Restoration of the Jews (London: Lincolns-Prager, 1956), pp. 117–124; David Fromkin, A Peace to End all Peace: The Fall of the Ottoman Empire and the Creation of the Modern Middle East (New York: Avon Books, 1989), pp. 267–268, 283, 298; Ronald Sanders, The High Walls of Jerusalem: A History of the Balfour Declaration and the Birth of the British Mandate for Palestine (New York: Holt, Rhinehart and Winston, 1983), pp. 73–74, 615. 4 Leonard Stein, The Balfour Declaration (London: Vallentine Mitchell, 1961). 5 Ibid., pp. 549–550. In his explanation of the Balfour Declaration David Lloyd George himself had emphasised the importance of the need for pro- Allied propaganda among Jewry. David Lloyd George, Memoirs of the Peace Conference, Vol. II (New Haven: Yale University Press, 1939), pp. 723–724. 6 Mayir Vereté, ‘The Balfour Declaration and its Makers’, Middle Eastern Studies, 6, 1 (Jan. -

The Americanization of Zionism, 1897–1948 Page I

Cohen: The Americanization of Zionism, 1897–1948 page i The Americanization of Zionism, 1897–1948 Cohen: The Americanization of Zionism, 1897–1948 page ii blank Cohen: The Americanization of Zionism, 1897–1948 page iii The Americanization of Zionism, 1897–1948 Naomi W. Cohen Brandeis University Press Cohen: The Americanization of Zionism, 1897–1948 page iv Brandeis University Press Published by University Press of New England, 37 Lafayette Street, Lebanon, NH 03766 © 2003 by Brandeis University All rights reserved This book was published with the generous support of the Lucius N. Litthauer Foundation, Inc. Printed in the United States of America 54321 Library of Congress Cataloguing-in-Publication Data Cohen, Naomi Wiener, 1927– The Americanization of Zionism, 1897–1948 / Naomi W. Cohen. p. cm. — (Brandeis series in American Jewish history, culture, and life) Includes bibliographical references and index. 1–58465–346–9 (alk. paper) 1. Zionism—United States—History. 2. Jews—Attitudes toward Israel. 3. Jews—United States—Politics and government—20th century. 4. Israel and the diaspora. I. Title. II. Series. .. 320.54'095694'0973—dc22 2003018067 Cohen: The Americanization of Zionism, 1897–1948 page v Brandeis Series in American Jewish History, Culture, and Life Jonathan D. Sarna, Sylvia Barack Fishman, . , The Americanization of the Synagogue, 1820–1870 , , Follow My Footprints: Changing Images of Women in American Jewish Fiction , Taking Root: The Origins of the Canadian Jewish Community , , Hebrew and the Bible -

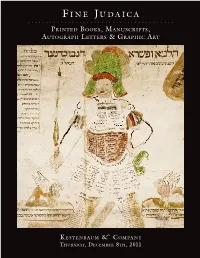

Fi N E Ju D a I

F i n e Ju d a i C a . pr i n t e d bo o K s , ma n u s C r i p t s , au t o g r a p h Le t t e r s & gr a p h i C ar t K e s t e n b a u m & Co m p a n y th u r s d a y , de C e m b e r 8t h , 2011 K e s t e n b a u m & Co m p a n y . Auctioneers of Rare Books, Manuscripts and Fine Art A Lot 334 Catalogue of F i n e Ju d a i C a . PRINTED BOOKS , MANUSCRI P TS , AUTOGRA P H LETTERS & GRA P HIC ART Featuring: Books from Jews’ College Library, London ——— To be Offered for Sale by Auction, Thursday, 8th December, 2011 at 3:00 pm precisely ——— Viewing Beforehand: Sunday, 4th December - 12:00 pm - 6:00 pm Monday, 5th December - 10:00 am - 6:00 pm Tuesday, 6th December - 10:00 am - 6:00 pm Wednesday 7th December - 10:00 am - 6:00 pm No Viewing on the Day of Sale. This Sale may be referred to as: “Omega” Sale Number Fifty-Three Illustrated Catalogues: $35 (US) * $42 (Overseas) KestenbauM & CoMpAny Auctioneers of Rare Books, Manuscripts and Fine Art . 242 West 30th street, 12th Floor, new york, NY 10001 • tel: 212 366-1197 • Fax: 212 366-1368 e-mail: [email protected] • World Wide Web site: www.Kestenbaum.net K e s t e n b a u m & Co m p a n y . -

How Jewish Was Justice Louis Brandeis? Russell G

Fordham Law School FLASH: The Fordham Law Archive of Scholarship and History Faculty Scholarship 2017 A Challenge to Bleached Out Professional Identity: How Jewish was Justice Louis Brandeis? Russell G. Pearce Fordham University School of Law, [email protected] Adam B. Winer NYU School of Law Emily Jenab Fordham University, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: http://ir.lawnet.fordham.edu/faculty_scholarship Part of the Legal Biography Commons, Legal Education Commons, and the Legal History Commons Recommended Citation Russell G. Pearce, Adam B. Winer, and Emily Jenab, A Challenge to Bleached Out Professional Identity: How Jewish was Justice Louis Brandeis?, 33 Touro L. Rev. 335 (2017) Available at: http://ir.lawnet.fordham.edu/faculty_scholarship/711 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by FLASH: The orF dham Law Archive of Scholarship and History. It has been accepted for inclusion in Faculty Scholarship by an authorized administrator of FLASH: The orF dham Law Archive of Scholarship and History. For more information, please contact [email protected]. A CHALLENGE TO BLEACHED OUT PROFESSIONAL IDENTITY: HOW JEWISH WAS JUSTICE LOUIS D. BRANDEIS? Russell G. Pearce, Adam B. Winer, and Emily Jenab I. INTRODUCTION Louis Brandeis is the most famous American Jewish jurist.1 The first Jew to sit on the Supreme Court of the United States, Brandeis earned acclaim as a brilliant corporate lawyer and preeminent Progressive legal thinker. He earned the accolade “the People’s Lawyer” through his advocacy against monopolies, support for workers’ rights, opposition to political corruption, robust defense of the rights to privacy and freedom of expression, and even served as a steward of the American Zionist movement during the critical World War I era.2 But despite his renown as a Jewish jurist, Brandeis’ Jewish identity has been the subject of considerable debate. -

The Judge and the President

The Judge and the President - How the American Zionist movement began Julie Selstø Roppestad Masteroppgave i historie, Institutt for arkeologi, konservering og historie UNIVERSITETET I OSLO Våren 2015 I II © Julie Selstø Roppestad 2015 The Judge and the President - How the American Zionist Movement Began Julie Selstø Roppestad http://www.duo.uio.no Trykk: Reprosentralen, Universitetet i Oslo III IV The Judge and the President - How the American Zionist movement began Julie Selstø Roppestad Masteroppgave i historie, Institutt for arkeologi, konservering og historie UNIVERSITETET I OSLO Våren 2015 V VI VII Summary With the release of Theodor Herzl’s “The Jewish State” in 1896, Zionism became a political movement with a clear goal; a Jewish homeland. The desire first arose in Europe, but soon American Jews followed suit. The American Zionist movement was riddled with internal strife from the get-go, and it took the involvement of “the People’s Attorney”, Louis D. Brandeis, and his friendship with the American President, Woodrow Wilson, to unite the American Zionists, at least for a little while. President Wilson quickly endorsed the Balfour Declaration, largely because of his friendship with Brandeis. This thesis is about the period between 1897 and 1930, and the main focus is on Louis D. Brandeis and the impact his leadership and his friendship with President Wilson had on the American Zionist movement. VIII IX X XI Table of contents Summary………………………………………………………………………… VIII 1. Introduction…………………………………………………………………………. 1 1.1 The Origins of Zionism…………………………………………………..………. 2 1.2 Political Zionism…………………………………………………….…………… 4 1.3 A Short History of the Jews of America………………………………….……… 6 1.4 Scope & Limitations……………………………………………………………… 8 1.5 Sources and literature…………………………………………….………………. -

The Greatest Jew in the World Since Jesus Christ: the Jewish Legacy Of

American Jewish History J. D. Sarna: The Jewish Legacy of Louis 0, Brandeis 347 81:3-4 (Spring-Summer 199 . 'Illc lise 01 hihlical i/llagcry :11111 rdigiolls Ianguagl' in l'unne(:tioll "The Greatest Jew in the World since Jesus Christ": The \\:1111 lIooal ~c,lorllIcrs is, ul "':UlIrllC, l;lI11iliar til students of American Jewish Legacy of Louis D. Brandeis III'itory. HdlglllllS vo...:ahlliarr is p;lrlll:llhll'ly ;lppropri;lIc in till' COil' text of Progressivism,. for many Progressivl' leaders gH'\\' lip in strict JONATHAN D. S,\RNA Protc!ltaut hOlllcs, tralllell as ministers, or at the vcry Icast had bccn stl'cred ill till' dirc...:tioll of llIinisteri;Jl illld lIIissiollarr careers, which ~!ler ~;lter rejected. l~~)bert CrunJcn Jubs thcsc Progrcssive Icadcrs IIll1llst~r!> of rclorlll and calls upon the vocabulary of rcligion in portra}'lIlg them: he speaks of "conversion" "sin " "Arnngcddoll " .. " I d ~ "', "Elijah," "Isaiah," "D:lIliel," "Moses," "Prophet," "J\tessiah," "the Spl ntua 0 ysseys." Greatest Jcw in the World Sin...:e Jesus Christ"-these arc only sOllle , BranJd~, however, forms an exception to all of these gcneraliza of thc man)' religious epithets attadled to the 11;11111.' of l.ulli .. Delllhit/, tlOns~ lIot Ilist becausc hc was a ,1l'w-there were uther Jewish Pro grandeis.' Ihandeis had the distinctioll of heing revered in his 0\\,11 gres~I\'es-h'n hecal1~e rdj~ioll pla)'ed a rdativdy insignificant role lifetime, and adlllirers-Jews and Christi;lIIs ;llike-scarclll:u for words III IllS upbrlllglllg., HIS grandtul1l'r and gn";lt-~rand(athl'r in Praglll' adequate to dcscribe him. -

THIS Volume Spans the Period Between October 1918, When

THE LETTERS AND PAPERS OF CHAIM WEIZMANN October 1918 – July 1920 Volume IX, Series A Introduction: Jehuda Reinharz General Editor Meyer W. Weisgal, Volume Editor Jehuda Reinharz, Research Editor: Pinhas Ofer, Transaction Books, Rutgers University and Israel Universities Press, Jerusalem, 1977 [Reprinted with express permission from the Weizmann Archives, Rehovot, Israel, by the Center for Israel Education www.israeled.org.] THIS volume spans the period between October 1918, when Chaim Weizmann, the head of the Zionist Commission, had just returned to England from Palestine, and July 1920, the month in which Herbert Samuel began his tenure as High Commissioner for Palestine and in which the Zionist Conference took place in London. These twenty-one months are of crucial importance for the history of Zionism and for the Jews in Palestine (the Yishuv). It is a period in which Weizmann's ascendancy to the leadership of the World Zionist Organization becomes undisputed. With unbounded energy Weizmann emerges as the prime mover and decision-maker concerning all important issues: the relations of the Zionists with the Palestinian Arabs and with Faisal, son of the Shereef of Mecca and Britain's wartime ally; the relations of the Zionists with the British in Palestine and London; the presentation of the Zionist case at the Peace Conference; the plight of Eastern European Jewry; cooperation among Zionists in Europe, Palestine and America; the dispatch of experts to Palestine; the future of the boundaries of Palestine. As a consequence Weizmann travels a great deal, pursuing these issues from London (October—December 1918; July—October 1919; January—February 1920 and May— July 1920) to Paris (January—June 1919) and Palestine (October—December 1919; March—April 1920). -

The a to Z of Zionism by Rafael Medoff and Chaim I

OTHER A TO Z GUIDES FROM THE SCARECROW PRESS, INC. 1. The A to Z of Buddhism by Charles S. Prebish, 2001. 2. The A to Z of Catholicism by William J. Collinge, 2001. 3. The A to Z of Hinduism by Bruce M. Sullivan, 2001. 4. The A to Z of Islam by Ludwig W. Adamec, 2002. 5. The A to Z of Slavery & Abolition by Martin A. Klein, 2002. 6. Terrorism: Assassins to Zealots by Sean Kendall Anderson and Stephen Sloan, 2003. 7. The A to Z of the Korean War by Paul M. Edwards, 2005. 8. The A to Z of the Cold War by Joseph Smith and Simon Davis, 2005. 9. The A to Z of the Vietnam War by Edwin E. Moise, 2005. 10. The A to Z of Science Fiction Literature by Brian Stableford, 2005. 11. The A to Z of the Holocaust by Jack R. Fischel, 2005. 12. The A to Z of Washington, D.C. by Robert Benedetto, Jane Dono- van, and Kathleen DuVall, 2005. 13. The A to Z of Taoism by Julian F. Pas, 2006. 14. The A to Z of the Renaissance by Charles G. Nauert, 2006. 15. The A to Z of Shinto by Stuart D. B. Picken, 2006. 16. The A to Z of Byzantium by John H. Rosser, 2006. 17. The A to Z of the Civil War by Terry L. Jones, 2006. 18. The A to Z of the Friends (Quakers) by Margery Post Abbott, Mary Ellen Chijioke, Pink Dandelion, and John William Oliver Jr., 2006 19. -

Revisiting British Zionism in the Early 20Th Century

W&M ScholarWorks Undergraduate Honors Theses Theses, Dissertations, & Master Projects 5-2021 Revisiting British Zionism in the Early 20th Century Benjamin Marin Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarworks.wm.edu/honorstheses Part of the European History Commons, History of Religion Commons, Islamic World and Near East History Commons, Jewish Studies Commons, Political History Commons, and the Social History Commons Recommended Citation Marin, Benjamin, "Revisiting British Zionism in the Early 20th Century" (2021). Undergraduate Honors Theses. Paper 1686. https://scholarworks.wm.edu/honorstheses/1686 This Honors Thesis -- Open Access is brought to you for free and open access by the Theses, Dissertations, & Master Projects at W&M ScholarWorks. It has been accepted for inclusion in Undergraduate Honors Theses by an authorized administrator of W&M ScholarWorks. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Revisiting British Zionism in the Early 20th Century A thesis submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirement for the degree of Bachelor of Arts / Science in Department from William & Mary by Benjamin A. Marin Accepted for Highest Honors ________________________________________ Dr. Michael Butler __ _____________________ Dr. Amy Limoncelli Dr. Mary Fraser Kirsh Williamsburg, VA May 3, 2021 For my grandfather, Alan Edelstein, whom I could easily imagine playing chess and talking science on those long transatlantic voyages with any number of early 20th Century Zionists. i Acknowledgements I would like to begin by thanking the members of the committee. To Professor Butler, I’m grateful that you took on this project in a field only tangentially related to your own area of expertise. Your guidance helped steer this project in a clear direction, and I came to appreciate your fastidious approach to grammar. -

Balfour Declaration - Wikipedia

2/22/2020 Balfour Declaration - Wikipedia Balfour Declaration The Balfour Declaration was a public statement Balfour Declaration issued by the British government in 1917 during the First World War announcing support for the establishment of a "national home for the Jewish people" in Palestine, then an Ottoman region with a small minority Jewish population. It read: His Majesty's government view with favour the establishment in Palestine of a national home for the Jewish people, and will use their best endeavours to facilitate the achievement of this object, it being clearly understood that nothing shall be done which may prejudice the civil and religious rights of existing non-Jewish communities in Palestine, or the rights and political status enjoyed by Jews in any other country. The declaration was contained in a letter dated 2 November 1917 from the United Kingdom's Foreign The Balfour Declaration, contained within the Secretary Arthur Balfour to Lord Rothschild, a leader of original letter from Balfour to Rothschild the British Jewish community, for transmission to the Created 2 November 1917 Zionist Federation of Great Britain and Ireland. The Location British Library text of the declaration was published in the press on 9 November 1917. Author(s) Walter Rothschild, Arthur Balfour, Leo Amery, Lord Milner Immediately following their declaration of war on the Signatories Arthur James Balfour Ottoman Empire in November 1914, the British War Purpose Confirming support from the Cabinet began to consider the future of Palestine; British government for the within two months a memorandum was circulated to establishment in Palestine of a the Cabinet by a Zionist Cabinet member, Herbert "national home" for the Jewish Samuel, proposing the support of Zionist ambitions in people, with two conditions order to enlist the support of Jews in the wider war. -

LOUIS BRANDEIS, Arthurf BALFOUR and a DECLARATION THAT MADE HISTORY

An enduring mystery in the story of giant combines of capital and indus LOUIS America and the Holy Land is why try. In his private life he was the typi Louis Dembitz Brandeis became a Zi cal assimilated Jew, totally unlettered BRANDEIS, onist. It was a strangely impulsive step in the Talmud or any formal religious for him, well into middle age, on the instruction. He never attended syna ARTHUrf eve of World War I. Given the times gogue; his relatives had married Gen and his reputation, Zionism was not tiles without inhibition. As he later BALFOUR AND the sort of cause that would come nat told British Foreign Secretary Lord urally to him. Doubts about his mo Balfour during one of their long and tives were raised from the start and mellow conversations, his entire life A DECLARATION have lingered on, half a century after "had been free from Jewish contacts his death. But whatever his motiva or traditions." Brandeis 's speeches THAT MADE tion, Brandeis 's act was to transform were full of literary allusions, but they the Jewish national cause in the rarely came from the Bible and those HISTORY American mind. that did were as likely to be from the The story of how a New Testament as from the Old. His Brandeis was born in Louisville, brother-in-law was Felix Adler, chance encounter Kentucky, in 1856. Both mother and founder of the Society for Ethical Cul on Cape Cod led to father, natives of Prague, came from ture, but even that offshoot of emanci dignified and emancipated families; pated Judaism held no interest for one of the most they transplanted the cultivated air of him. -

First Zionist Congress

First Zionist Congress Chair: Peter Mikulski Hello delegates, I’m Peter Mikulski, chair of the First Zionist Congress at LYMUN 2020. We’ve been waiting for you all summer long and we’re so glad you’re finally here! We are about to embark on a deep dive into the exciting world of Zionism in the late 19th century. I simply cannot wait! But first, a little about myself. I am a sophomore and serve on LTMUN’s underclassmen board. At last year’s LYMUN, I was the vice chair of the Trump’s Cabinet ad hoc committee. I’m interested in Islamic history, amateur radio, and music. In this committee, you will assume the role of the men (and one woman) present at the First Zionist Congress held in 1897 in Basel, Switzerland. Zionism -- the belief in the necessity of Jewish statehood -- is multifaceted. Many men believing very different things called themselves Zionists, so I hope your research is thorough and you come to LYMUN VII with a good grasp of the issues discussed at the First Congress. Well done research will make participating in debate and the resolution writing exponentially easier. It’ll also make the 1 committee’s outcome more interesting for everyone! The following background guide I’ve written will be a good place to start, but, of course, it should not be your only source. Every delegate must complete a position paper (one page for each topic) to be eligible for awards in this committee. Additionally, I hope each of you will speak up in our session at least once.