When the Earthquake Hit

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

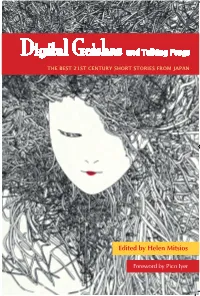

Digital Geishas Sample 4.Pdf

Literature/Asian Studies Digital Geishas Digital Digital Geishas and Talking Frogs THE BEST 21ST CENTURY SHORT STORIES FROM JAPAN Digital Geishas and Talking Frogs With a foreword by Pico Iyer and Talking Frogs THE BEST 21ST CENTURY SHORT STORIES FROM JAPAN This collection of short stories features the most up-to-date and exciting writing from the most popular and celebrated authors in Japan today. These wildly imaginative and boundary-bursting stories reveal fascinating and unexpected personal responses to the changes raging through today’s Japan. Along with some of the THE BEST 21 world’s most renowned Japanese authors, Digital Geishas and Talking Frogs includes many writers making their English-language debut. ST “Great stories rewire your brain, and in these tales you can feel your mind C E shifting as often as Mizue changes trains at the Shinagawa station in N T ‘My Slightly Crooked Brooch…’ The contemporary short stories in this URY SHO collection, at times subversive, astonishing and heart-rending, are brimming with originality and genius.” R —David Dalton, author of Pop: The Genius of Andy Warhol T STO R “Here are stories that arrive from our global future, made from shards IES FR of many local, personal pasts. In the age of anime, amazingly, Japanese literature thrives.” O M JAPAN —Paul Anderer, Professor of Japanese, Columbia University About the Editor H EDITED BY Helen Mitsios is the editor of New Japanese Voices: The Best Contemporary Fiction from Japan, which was twice listed as a New York Times Book Review Editors’ Choice. She has recently co-authored the memoir Waltzing with the Enemy: A Mother and Daughter Confront the Aftermath of the Holocaust. -

Ride on Time

Japan Earthquake Charity Literature 아베 가즈시게 RIDE ON TIME 김훈아 옮김 WasedaBungaku 2012 RIDE ON TIME 오늘도 파도가 신통치 않다. 바람은 그저 차갑기만 할 뿐. 문 득 생각난 듯 타성처럼 일어서는 해산물집 포렴과 장대에 달아 놓은 깃발을 펄럭거리고 지나간다. 그리고 남는 건 기껏 바다 냄새와 모래 먼지의 잔상뿐이다. 오늘 것도 어제 것도 그리고 내일 것도 아마 비슷할 것이다. 특기할 사항이라고는 아무것도 없는, 평범하기 그지없는 그저 그런 파도들뿐. 그렇지만 실은 이렇게 불평을 늘어놓을 만큼 나쁘지 않다는 것도 잘 안다. 단지 우리가 이곳의 파도에 너무 익숙해져 자극이 엷어진 것 뿐이다. 오랫동안 이 해변에 눌러앉아 허구한 날 게팅 아웃⁽¹⁾ 을 하 는 동안, 이곳 특유의 풍랑에 완전히 익숙해져버린 우리는, 어 지간한 변화에는 놀라지 않게 된 것이다. 사치스럽게도 별이 달린 음식을 일상적으로 먹으면서 이런 게 아니라 더 나은 것, 하고 구름 위의 존재인 요리장에 욕설만 퍼붓고 있다. 기상청에다 화풀이하는 건 이미 지쳤기 때문에 굳이 시끄럽게 굴진 않는다. 둥지 속의 새끼들처럼 고개를 쳐들 고 그저 먹이를 받아먹고 있을 뿐. 먹이가 오기를 기다리다 이 따금 삑삑하고 울고 있는 것이다. 이런 상황 자체가 지긋지긋한 지도 오래됐지만, 우리는 여전 히 이곳에 머물러 있다. 그것은 오로지 그 파도가 다시 몰려 올 것이란 기대를 버리지 않고 있기 때문이다. 그 파도가 현실이었다는 것을 아직 믿지 못하는 사람도 적지 않다. 십 년 전을 마지막으로 아직 한 번도 모습을 드러내지 않은, 상상을 초월하는 그랜드 스웰(Grand Swell). (1) Getting out, 서퍼가 파도를 타고 라이딩을 시작하는 것 2 RIDE ON TIME 하늘을 뒤덮은 듯한 거대한 해룡의 날갯짓하던 모습을 떠올 리며, 우리는 그것이 다시 찾아오기를 간절히 기다리고 있다. 한결같이 재도전의 기회를 노리는 베테랑이 있는가 하면, 파 도의 규모나 출현에도 반신반의인 루키도 있다. 어느 쪽이건 전 설과의 대치를 갈망하는 자들뿐이다. -

Mieko Kawakami Translated from the Japanese by Sam Bett and David Boyd

Europa editions MARCH-JULY 2021 Europa editions Distributed by PGW Heaven Mieko Kawakami Translated from the Japanese by Sam Bett and David Boyd From the best-selling author of Breasts and Eggs and international cause célèbre Mieko Kawakami, a sharp and illuminating novel about the power of friendship and solidarity to combat life’s challenges. Kawakami’s novel is told in the voice of a 14-year-old school student subjected to bullying by his classmates. MIEKO The only person who understands his ordeal is a female classmate who suffers similar treatment at KAWAKAMI the hands of her tormenters. Each finds in the other not only solace but a unique sensibility that opens HEAVEN up new perspectives on their predicaments. A NOVEL Revelatory, raw, and incisive, Kawakami’s portrayals of two young people in need are drawn with profound tenderness and framed within a nuanced exposition on the effects and of violence and the importance of Europa editions solidarity. Breasts and Eggs announced Kawakami as a captivating storyteller, and as an author committed Marketing & Publicity to expanding the boundaries of contemporary • Spring 2021 Lead Title Japanese literature. Heaven stands as a dazzling • Paperback of Breasts and Eggs publishing in March confirmation of her literary talent and broad appeal • A third Kawakami novel, The Night Belongs to Lovers, coming soon. and will find favor with readers of the best • Dedicated Publicist for press reviews, features, interviews, contemporary literary fiction. influencer campaign • High-profile national and -

Ride on Time

Japan Earthquake Charity Literature Kazushige Abe RIDE ON TIME Translated by Michael Emmerich WasedaBungaku 2011 RIDE ON TIME Another day of uninspiring waves. Nothing bracing about the wind, either – it just feels chilly. Occasionally a perfunctory gust springs up, as if it’s suddenly realized it should have been blowing all along, flapping the banners outside the seafood shops and the curtains hanging in the storefronts before head- ing elsewhere. In its wake, the salty pungency of the rocks and an image on the retina of billowing sand. The waves are always the same. It was like this yesterday, and doubtless it’ll be this way tomorrow, too. Bland, ordinary swells, unremarkable, average. Still, we know they’re not as bad as we say they are. Truth is, we’ve gotten used to them. Inured to their excite- ments. Having spent so many years on this coast, paddling out past the breakers day in and day out, all year long, we’ve become so familiar with the particular qualities of the wind and waves here that there are no surprises anymore, unless something well out of the ordinary comes along. Lucky enough to be served gourmet meals on a daily basis, we grumble about the cooks above the clouds. This isn’t good enough, do better! Blaming the weather bureau has gotten so old that we no longer even bother. We’re as passive as chicks in a nest, straining upward, opening our mouths, cheeping 2 RIDE ON TIME shrilly ever so often as we wait for our food. We’ve long since become bored with the whole situation, but that doesn’t keep us from staying on. -

Poola's Return

Japan Earthquake Charity Literature Hideo Furukawa Poola’s Return Translated by Satoshi Katagiri WasedaBungaku 2011 Poola’s Return Moments like these remind me of Poola. I may have used the wrong words. It may be best to cor- rect them by saying, “All I can remember now...” But what is “best”? Many images have changed meanings in many people after “that day”. In such a case, all I can do is remember truth- ful to this moment, to this now. All I can do is look back. I don’t think I have time to hesitate. I don’t think it is good to hesitate, either. The line between good and evil has disappeared. So I try to remember, and be true to how it happened. A girl once told me a story. Parts of it rang like a candid confession. It was true and personal. I’ve never forgotten her voice. I never forgot it but this now I remember it. Poola lives in a middle school that the girl once used to attend. Ten years passed since her middle school years, and she did not know Poola back then. “I don’t think it existed when I was there,” she said. I can almost hear her voice in my head. Her voice (indeed the voice) is what is pulling me back to memories. Poola lives in the school pool. Poola lives there until all the water is dried out for the win- ter. Poola never comes out during summer. 2 Poola’s Return Poola might be a nocturnal creature.