Probable Object Play Among Gulls in Staffordshire Juvenile Common

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Derbyshire Gritstone Way

A Walker's Guide By Steve Burton Max Maughan Ian Quarrington TT HHEE DDEE RRBB YYSS HHII RREE GGRRII TTSS TTOONNEE WW AAYY A Walker's Guide By Steve Burton Max Maughan Ian Quarrington (Members of the Derby Group of the Ramblers' Association) The Derbyshire Gritstone Way First published by Thornhill Press, 24 Moorend Road Cheltenham Copyright Derby Group Ramblers, 1980 ISBN 0 904110 88 5 The maps are based upon the relevant Ordnance Survey Maps with the permission of the controller of Her Majesty's Stationery Office, Crown Copyright reserved CONTENTS Foreward.............................................................................................................................. 5 Introduction......................................................................................................................... 6 Derby - Breadsall................................................................................................................. 8 Breadsall - Eaton Park Wood............................................................................................ 13 Eaton Park Wood - Milford............................................................................................... 14 Milford - Belper................................................................................................................ 16 Belper - Ridgeway............................................................................................................. 18 Ridgeway - Whatstandwell.............................................................................................. -

4-Night Peak District Family Walking Adventure

4-Night Peak District Family Walking Adventure Tour Style: Family Walking Holidays Destinations: Peak District & England Trip code: DVFAM-4 1, 3 & 4 HOLIDAY OVERVIEW The UK’s oldest national park is a land of pretty villages, limestone valleys and outcrops of millstone grit. The area is full of rural charm with a range of walks. Leg-stretching hikes up to gritstone edges reward with sweeping views while riverside walks see the hills from a different perspective. Follow the High Peak Trail to the lead mining villages of Brassington and Carsington, take the Tissington Trail for views of Dovedale Gorge and walk through the grounds of Chatsworth House. If you need to refuel, a stop off in Bakewell for a slice of its famous tart is highly recommended! WHAT'S INCLUDED • Full Board en-suite accommodation. • A full programme of walks guided by HF Leaders • All transport to and from the walks • Free Wi-Fi www.hfholidays.co.uk PAGE 1 [email protected] Tel: +44(0) 20 3974 8865 HOLIDAYS HIGHLIGHTS • Cross the River Dove at the famous Stepping Stones • Explore the historic town of Buxton • Discover Derbyshire’s industrial heritage at the National Stone Centre TRIP SUITABILITY This trip is graded Activity Level 1, level 3 and level 4. There are four different length guided walks to choose from each walking day: • Family - approx. 4 miles • Easy - approx. 6-7 miles • Medium - approx. 8 miles • Hard - approx. 9-10 miles ITINERARY ACCOMMODATION The Peveril Of The Peak The Peveril of the Peak, named after Sir Walter Scott’s novel, stands proudly in the Peak District countryside, close to the village of Thorpe. -

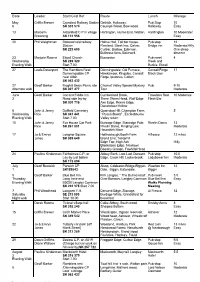

See Notes on Second Sheet Date Leader Start/Grid Ref. Route Lunch

Date Leader Start/Grid Ref. Route Lunch Mileage May Griffin Brewer Cromford Railway Station Dethick, Holloway, Pub Stop 10 6 SK 303 574 Coumps Wood, Bow wood. Holloway Easy 13 Malcolm Alstonfield C P in village Hartington, Hulme End, Wetton, Harrtington 10 Moderate/ Browning SK 131 556 Easy 20 Phil Weightman Bakewell old railway Holme Hall, Toll bar house, Pub stop 12 Station Rowland, Bleak low, Calver, Bridge inn Moderate/Hilly. SK 223 690 Curbar, Baslow, Edensor, One steep Bullcross farm, Bakewell. descent 23 Marjorie Roome Etwall Church Burnaston Pub meet 4 Wednesday SK 269 320 Hawk and Evening Walk Start 7.00 Buckle. Etwall 27 Lewis Davenport The Ramblers Rest/ Dimmingsdale, Old Furnace, Consall Forge 17 Dummingsdale CP Hawksmoor, Kingsley, Consall Black Lion near Alton Forge, Ipstones, Cotton. SK 063 432 27 Geoff Barker Froghill Basin Picnic site Churnet Valley Special Mystery Pub 9-10 Alternate walk SK 027 477 Tour Moderate June Geoff Barker Cat and Fiddle Inn Cumberland Brook, Travellers Rest 10 Moderate 3 Road side lay-by Three Shires Head, Wolf Edge Flash Bar SK 001 718 Axe Edge, Reeve Edge, Danebower Hollow 6 John & Jenny Duffield Cemetery Quarndon Hill, Champion Farm, 5 Wednesday Rice SK 341 441 “Puss in Boots”, Ecclesbourne Evening Walk Start 7.00 Valley return 10 John & Jenny Fox House Car Park Burbage Edge, Stanedge Pole, Rivelin Dams 13 Rice SK 267 801 Rivelin Dams, Ringing Low, Moderate Houndkirk Moor 17 Jo & Emrys Longnor Square Hollinsclough,Booth Farm Alfresco 12 miles Jones SK 089 649 Brand End, Tenterhill Edge Top ,High Ash Hilly Blackstone Edge, Newtown Boosley Grange, Fawfield Head 24 Pauline Kinderman Fairholmes C.P. -

Derbyshire Parish Registers. Marriages

Gc Kf!l& 942.51019 Aalp V.12 1379100 GENEALOGY COLLECTION ALLEN COUNTY PUBLIC LIBRARY 833 00727 4324 General Editor ... ... T, M. Blagg, F.S.A. DERBYSHIRE PARISH REGISTERS, XII. phili.imork's parish register series. vol. ccvi. (pekbvskire, vol. xil). One hundred and fifty printed. : Derbyshire Parish Registers General Editor : THOS. M. BLAGG, F.S.A. VOL. XII. Edited by W. BRAYLESFORD BUNTING AND Ll. LLOYD SIMPSON. ft c^ t fj ILonlron Issued to the Subscribers by Phillimore & Co., Ltd., 124, Chancery Lane. 1914. PREFACE. So many parishes in S.E. Derbyshire have been dealt with in this Series that it was hoped and intended that the present volume would be devoted entirely to the High Peak district and would contain a compact group of adjacent parishes, an arrangement which always brings out in a peculiar degree the value of this method of printing the complete Marriage Registers of a whole district. Unfortunately it was not found possible to obtain sufficient MS. from the High Peak without delaying indefinitely the issue of the volume, already overdue. The latter third of the book, therefore, has been filled with the important Register of Repton, the MS. of which had been ready for some time. The Repton abstracts were made by Mr. Simpson and Mr. E. B. Smith ; those of Chapel-en-le-Frith, which contain so many entries of old-established Peak families as to be of exceptional interest to genealogists, were done by of Fairfield Mr. W. Braylesford Bunting ,; and those and Buxton are kindly supplied by Mr. John Brandreth and Mr. -

Macclesfield to Buxton

Macclesfield to Buxton 1st walk check 2nd walk check 3rd walk check 16th June 2021 Current status Document last updated Thursday, 12th August 2021 This document and information herein are copyrighted to Saturday Walkers’ Club. If you are interested in printing or displaying any of this material, Saturday Walkers’ Club grants permission to use, copy, and distribute this document delivered from this World Wide Web server with the following conditions: • The document will not be edited or abridged, and the material will be produced exactly as it appears. Modification of the material or use of it for any other purpose is a violation of our copyright and other proprietary rights. • Reproduction of this document is for free distribution and will not be sold. • This permission is granted for a one-time distribution. • All copies, links, or pages of the documents must carry the following copyright notice and this permission notice: Saturday Walkers’ Club, Copyright © 2021, used with permission. All rights reserved. www.walkingclub.org.uk This walk has been checked as noted above, however the publisher cannot accept responsibility for any problems encountered by readers. Macclesfield to Buxton (via the Cat & Fiddle) Start: Macclesfield Station Finish: Buxton Station Macclesfield Station, map reference SJ 919 736, is 237 km northwest of Charing Cross, 133m above sea level and in Cheshire East. Buxton Station, map reference SK 059 737, is 22km southeast of Manchester, 299m above sea level and in Derbyshire. Length: 25.2 km (15.7 mi). Cumulative ascent/descent: 971/805m. For a shorter or longer walk, see below Walk options. -

JBA Consulting

Land at Elnor Lane Farm, Whaley Bridge: LVA Note to file 1.1 JBA Comments on views from National Park JBA Consulting provided a Landscape and Visual (LV) supplementary information report to accompany an outline planning application for 82 dwellings on land to the southern edge of Whaley Bridge in Derbyshire. The report include a review of relevant policy/evidence base documents and a summary of likely landscape and visual effects, accompanied by viewpoints from key locations and a Zone of Theoretical Visibility (ZTV) drawing. The potential for adverse impacts on the Park were raised during the Local Plan housing allocation process. The supplementary LV report considered that views from the Park were limited, being largely restricted to high ground of Taxal Moor, around 1.5km to the southwest. It concluded that, where visible, it may locally be noticeable but represent “little or no intrusion outside the existing settlement edge and would be a minor element in expansive views”. Representations were subsequently received from the Park Authority during the application stage: The Authority is concerned that the proposal is a visible intrusion into the landscape and therefore harmful to the flow of landscape character beyond the National Park boundary. It would detract from the setting of the National Park . While the site is not very visible from the roads (Elnor Lane and the [A]5004) due to aspect, high hedges & trees, the developers own Zone of Theoretical Visibility drawing shows that it is visible from large expanses of the adjacent national park, especially of Taxal Moor. Further to these comments, a sketch visualisation was prepared by others to demonstrate potential views from Taxal Moor. -

Peak Area Newsletter November 2017 Access Or Activity Problems

PEAK AREA The Great Ridge. Photo: John Coefield. NEWSLETTER November 2017 [email protected] Rocking Chair to key personnel, the soon-to-be-enforced Rob Greenwood parking charges and a lack of management plan for the site, I suspect the presentation We’ve had some and Q&A that will follow will involve some big meetings over the lively discussion/feedback. past few years, but this one could After this we’ll have our AGM, of which eclipse the lot with two major the key item of interest is the voting in of items on the agenda that are of our National Council representatives. such magnitude our format will Keep an eye out for each candidate’s change a little – starting at an personal statement, which will be coming earlier time of 6.30 (with food via email alongside the newsletter. being served from 6 p.m. onwards). Next up is the single largest agenda Things kick off with a presentation item that has probably ever been covered from Sarah Fowler, Chief Executive of the at a Peak Area meeting: the results of the Peak District National Park Authority. As BMC’s Organisational Review. This, with no regular attendees will be aware, Stanage exaggeration, could involve changes to the has been a regular feature on our agenda fabric of the BMC as we know it and your over the past few years, and with changes feedback as members is essential. Cont ... Next meeting: Wednesday 22 November, 6.30 p.m. The Maynard, Grindleford, S32 2HE Hiiggar Tor.. Photo::John Coefiielld. -

Dark Peak Boundary Walk

DARK PEAK BOUNDARY WALK The title 'Boundary Walk' refers to the nature of the walk, a circuit of 80 miles around the fringes of three great moorland masses of Kinder Scout, Bleaklow and Black Hill that comprise the Dark Peak. The route is mainly high level but linking these sections a variety of terrain including bridleway tracks, field paths, sheltered wooded cloughs and numerous reservoirs will be encountered. The bleak and wild moors of the Dark ·Peak are never far away and often dominate the views. The route was completed to my satisfaction in November 1987 having been put together on occasional weekend trips over a couple of years. My intention was to create an enjoyable (hopefully) circular walk suitable for short hostelling/backpacking holidays. The entire route is covered by OS Sheet 110 (1:50,000) Sheffield and Huddersfield area. Route Outline From Sett Valley car park, Hayfield via Cracken Edge - South Head - Dimpus Gate Rushup Edge - Rowter Farm - Bradwell Moor - Bradwell. Abney Moor - Leadmill Bridge - Hathersage. Mitchell Field - Carl Walk - Burbage Brook - Stanage Edge - Moscar Lodge - Sugworth Hall - Strines- Back Tor - Margery Hill - Cut Gate - Langsett. Carlecotes - Dunford Bridge - Winscar Reservoir - Holme - Wessenden Head - Marsden. Redbrook Reservoir - Diggle - Aldermans Hill - Dove Stone Reservoir - Chew Reservoir - Tintwistle - Padfield - Old Glossop. Cown Edge - Rowarth - Lantern Pike - Birch Vale - Sett Valley Trail back to Hayfield. Suggested four day tour:- Day One Hayfield to Hathersage 20 Miles YH Day Two Hathersage to Langsett 21 miles YH Day Three Langsett to Marsden 16 miles B&B Final Day Marsden to Hayfield 25 miles Accommodation There are excellent Youth Hostels at Hathersage and Langsett. -

Making Connections a Landscape Scale Vision for the Sheffield Moors

Making connections a landscape scale vision for the Sheffield Moors Masterplan 2013–2028 Making connections a landscape scale vision for the Sheffield Moors Masterplan 2013–2028 First published in 2014 by The Sheffield Moors Partnership www.sheffieldmoors.co.uk Design, typesetting and origination by FDA Design Limited Hathersage, Hope Valley, Derbyshire S32 1BB www.fdadesign.co.uk Printed by W&G Baird Ltd ISBN 978 0 9564452 6 1 © The Sheffield Moors Partnership 2014 The right of the authors to be identified as the authors of this work has been asserted by them in accordance with the Copyright, Designs and Patents Act 1988 All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in or introduced into a retrieval system, or transmitted, in any form, or by any means (electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording or otherwise) without the prior written permission of the publisher. Any person who does any unauthorized act in relation to this publication may be liable to criminal prosecution and civil claims for damages Front cover (main image): View of Higger Tor from Owler Tor, Burbage Moors, Karen Frenkel Front cover (small images): Merlin, Philip Newman; Mountain biking, Adam Long; Volunteers at Longshaw, National Trust; Highland cattle, National Trust Title page: Stanage Edge, Karen Frenkel Back cover: Millstones on Stanage Edge, Karen Frenkel 2 Contents 5 The Sheffield Moors: making connections at a landscape scale 9 Our vision 11 The Sheffield Moors in the Peak District 15 What makes the Sheffield Moors so special? -

Peak Area Newsletter

PEAK AREA Name the crag. Photo: John Coefield. NEWSLETTER September 2017 [email protected] Rocking Chair future of the crag but are not yet in a Rob Greenwood position to confirm plans. Finally, just to unravel one final loose end: we have had There is a lot going on three interested parties approach us behind the scenes at regarding the role of National Council the moment. representative for the Peak Area … but The organisational review is well none of them can actually make the next underway, with the first summary/report meeting … due … shortly after the next round of area On the bright side it looks like Simon Lee, meetings.Talks have taken place between the regular attendee of the Peak Area meetings Peak District National Park Authority and and recently appointed Commercial the BMC regarding the future of Stanage, Partnerships Manager at the BMC, has made after concerns were voiced at the last Peak tangible progress in acquiring a retail partner Area meeting; however a conclusion is likely and – in a completely unrelated note – to be reached – you guessed it – shortly rebolting at Horseshoe Quarry has now after the next area meeting. begun. If this isn’t enough, I’m sure there’ll Buxton Mountaineering Club, custodians be more to discuss on the night. of Aldery, have had a meeting regarding the For now – see you there. Next meeting: Wednesday 13 September, 7.30 p.m. The Maynard, Grindleford, S32 2HE Wiimberry.. Photo::John Coefiielld.. Access News is to drive there. It used to be possible to Henry Folkard park in one or two informal lay-bys, but these have been blocked off by large Dark Peak boulders by persons unknown – presumably It is in the nature of the landowner. -

Archaeology and Conservation in Derbyshire

ISSUE 13 JANUARY 2016 ACIDArchaeology and Conservation in Derbyshire Lord of all it Inside: surveys Tony Robinson profile Rushup Edge’s bowl barrow The laughing stock of Creswell Moor than meets the eye 2 015 | ACID 1 Plus: A guide to the county’s latest planning applications involving archaeology View from the chair Foreword: ACID Archaeology and Conservation in Derbyshire Editor: Roly Smith, Discoveries by 33 Park Road, Bakewell, Derbyshire DE45 1AX Tel: 01629 812034; email: [email protected] For further information (or more copies) please accident or design email Ken Smith at: [email protected] elcome to our annual round-up of highlights from archaeological and Designed by: Phil Cunningham heritage activities in the county during 2015. As usual a great variety of www.creative-magazine-designer.co.uk Wthings have happened, some by design others by accident, involving many Printed by: Buxton Press www.buxtonpress.com individuals as a part of their work, education or leisure pursuits. Derbyshire Archaeology Advisory Committee Archaeology and heritage are essentially democratic in their appeal and the Buxton Museum opportunities they offer, a characteristic well understood by Tony Robinson, the Creswell Crags Heritage Trust Derbyshire Archaeological Society subject of this year’s revealing profile by our Editor Roly Smith, set against the Derbyshire County Council dramatic background of Kinder Scout. Well-known author David Hey chose to write Derby Museums Service about another local moorland, the Longshaw Estate, and some of its less well-known Historic England (East Midlands) Hunter Archaeological Society heritage features, visible to anyone who knows where and how to look. -

Carl Wark Hillfort, Hathersage, Derbyshire: Conservation Management Plan

CARL WARK HILLFORT, HATHERSAGE, DERBYSHIRE: CONSERVATION MANAGEMENT PLAN CONSERVATION MANAGEMENT PLAN Report Number 2014/19 June 2014 ArcHeritage is a trading name of York Archaeological Trust. The Trust undertakes a wide range of urban and rural archaeological consultancies, surveys, evaluations, assessments and excavations for commercial, academic and charitable clients. We manage projects, provide professional advice and fieldwork to ensure a high quality, cost effective archaeological and heritage service. Our staff have a considerable depth and variety of professional experience and an international reputation for research, development and maximising the public, educational and commercial benefits of archaeology. Based in York, Sheffield, Nottingham and Glasgow the Trust’s services are available throughout Britain and beyond. ArcHeritage, Campo House, 54 Campo Lane, Sheffield S1 2EG Phone: +44 (0)114 2728884 Fax: +44 (0)114 3279793 [email protected] www.archeritage.co.uk © 2014 York Archaeological Trust for Excavation and Research Limited Registered Office: 47 Aldwark, York YO1 7BX A Company Limited by Guarantee. Registered in England No. 1430801 A registered Charity in England & Wales (No. 509060) and Scotland (No. SCO42846) ArcHeritage i CONTENTS KEY PROJECT INFORMATION .......................................................................................................... IV SUMMARY ...................................................................................................................................... VI