How Molecules Became Machines

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Volume 74, No. 4, October 2010

Inside Volume 74, No.4, October 2010 Articles and Features 129 Rotaxanes as Molecular Machines – The Work of Professor David Leigh Anthea Blackburn 136 Hydrated Complexes in Earth’s Atmosphere Anna L. Garden and Henrik G. Kjaergaard 141 Healthy Harbour Watchers: Community-Based Water Quality Monitoring and Chemistry Education in Dunedin Andrew Innes, Steven A. Rusak, Barrie M. Peake and David S. Warren 145 Hot Chemistry from Horopito Nigel B. Perry and Kevin S. Gould 149 Jan Romuald Zdysiewicz, FRACI (1943–2010) Jennifer M. Bennett and Donald W. Cameron 150 Earthquakes and Chemistry Anthea Lees Other Columns 122 NZIC October News 157 Grants and Awards 151 Patent Proze 158 IYC 2011 152 ChemScrapes 159 Subject Index 2010 153 Dates of Note 160 Author Index 2010 156 Conference Calendar Advertisers Inside front cover Thermo Fisher Scientific Editorial 135 NZIC Annual General Meeting Inside back cover Pacifichem Back cover NZ Scientific On the Cover Horopito leaves from http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/File:Pseudowinteracolorata.jpg – see P 145 121 Chemistry in New Zealand October 2010 New Zealand Institute of Chemistry supporting chemical sciences October News NZIC News Comment from the President and ICY 2011 It is now just a few months until the end of the 2010 – ships with groups such as and that means the start of the 2011 International Year of teachers (both high school Chemistry. I am pleased to report that the major NZIC and primary) and, in my events have been planned and a programme of events for experience, NZIC needs the year written. These will all have been discussed by to demonstrate how it can Council at its September 3 meeting when this is in press. -

Horizon Europe - EU Multiannual Financial Framework

30 November 2018 Dear Prime Minister / Chancellor / Taoiseach / President, Horizon Europe - EU Multiannual Financial Framework (a letter to Heads of State or Government, signed by Nobel Prize and other international award winners and CEOs and Chairmen of leading European companies) At the European Council meeting in December, European leaders will discuss the 2021-2027 EU Multiannual Financial Framework, including the budget to be assigned to Research and Innovation, mainly through the next framework programme Horizon Europe. On this occasion, we want to remind them of the economic impact and the tangible improvements to European citizens' lives that have been generated over the years by the EU framework programmes for Research and Innovation. We urge Europe’s Heads of State or Government to support or even to increase the investment in Horizon Europe. €120 billion was seen as the absolute minimum to make Europe a global frontrunner by the High Level Group set by the European Commission and chaired by Pascal Lamy. Indeed, EU-funded research had a decisive impact and positively contributed to various areas, such as avoiding unnecessary chemotherapy for breast cancer patients; opening the way to batteries and solar cells of the next generation; reducing aircraft emissions and noise; enhancing cybersecurity; qualifying the future impact of artificial intelligence on jobs; etc. European industry underlines that the EU framework programmes help companies to build up know-how, have access to the “state-of-the-art”, achieve synergies and critical mass, access highly skilled and talented people, and network with customers and suppliers. EU-funded research has made an immense contribution to creating and disseminating scientific knowledge indispensable for innovation to flourish. -

What Use Is Chemistry?

2 Inspirational chemistry What use is chemistry? Index 1.1 1 sheet This activity is based on a Sunday Times article by Sir Harry Kroto, a Nobel prize winning chemist who discovered a new allotrope of carbon – buckminsterfullerene or ‘bucky balls’. The article appeared on November 28, 2004 and is reproduced overleaf as a background for teachers. The aim is to introduce students to the scope of modern chemistry and the impact that it has on their lives, even in areas that they may not think of as related to chemistry. An alternative exercise for more able students would be to research what was used before chemical scientists had produced a particular new product or material (eg silk or wool stockings before nylon, leather footballs before synthetics, grated carbolic soap before shampoo) and then to write about the difference it would make to their lives if they did not have the modern product. Students will need: ■ Plenty of old magazines and catalogues (Argos catalogues are good as virtually everything in them would not exist without modern chemistry) ■ Large sheets of sugar paper ■ Glue and scissors. It works well if students produce the poster in groups, but then do the written work by themselves. The activity could be set for homework. Inspirational chemistry 3 What use is chemistry? Some years ago I was delighted chemistry-related industries make a to receive an honorary degree £5 billion profit on a £50 billion from Exeter University turnover, the apparent government recognising my contributions to inaction over the looming disaster chemistry – especially the is scarcely credible. -

Design, Synthesis, Photochemical and Biological Evaluation of Novel Photoactive Molecular Switches

TESIS DOCTORAL Título Design, Synthesis, Photochemical and Biological Evaluation of Novel Photoactive Molecular Switches Autor/es David Martínez López Director/es Diego Sampedro Ruiz y Pedro José Campos García Facultad Facultad de Ciencia y Tecnología Titulación Departamento Química Curso Académico Design, Synthesis, Photochemical and Biological Evaluation of Novel Photoactive Molecular Switches, tesis doctoral de David Martínez López, dirigida por Diego Sampedro Ruiz y Pedro José Campos García (publicada por la Universidad de La Rioja), se difunde bajo una Licencia Creative Commons Reconocimiento-NoComercial- SinObraDerivada 3.0 Unported. ̉ Permisos que vayan más allá de lo cubierto por esta licencia pueden solicitarse a los titulares del copyright. © El autor © Universidad de La Rioja, Servicio de Publicaciones, 2019 publicaciones.unirioja.es E-mail: [email protected] Facultad de Ciencia y Tecnología Departamento de Química Área de Química Orgánica Grupo de Fotoquímica Orgánica TESIS DOCTORAL DESIGN, SYNTHESIS, PHOTOCHEMICAL AND BIOLOGICAL EVALUATION OF NOVEL PHOTOACTIVE MOLECULAR SWITCHES Memoria presentada en la Universidad de La Rioja para optar al grado de Doctor en Química por: David Martínez López Junio 2019 Facultad de Ciencia y Tecnología Departamento de Química Área de Química Orgánica Grupo de Fotoquímica Orgánica D. DIEGO SAMPEDRO RUIZ, Profesor Titular de Química Orgánica del Departamento de Química de la Universidad de La Rioja, y D. PEDRO JOSÉ CAMPOS GARCÍA, Catedrático de Química Orgánica del Departamento de Química de la Universidad de La Rioja. CERTIFICAN: Que la presente memoria, titulada “Design, synthesis, photochemical and biological evaluation of novel photoactive molecular switches”, ha sido realizada en el Departamento de Química de La Universidad de La Rioja bajo su dirección por el Licenciado en Química D. -

Chartered Status Charteredeverything You Need Tostatus Know Everything You Need to Know

Chartered Status CharteredEverything you need toStatus know Everything you need to know www.rsc.org/cchem www.rsc.org/cchem ‘The best of any profession is always chartered’ The RSC would like to thank its members (pictured top to bottom) Ben Greener, Pfizer, Elaine Baxter, Procter & Gamble, and Richard Sleeman, Mass Spec Analytical Ltd, for their participation and support . Chartered Status | 1 Contents About chartered status 3 Why become chartered? 3 What skills and experience do I need? 3 The professional attributes for a Chartered Chemist 5 Supporting you throughout the programme yThe Professional Development Programme 5 yThe Direct Programme 7 How to apply 7 Achieving Chartered Scientist status 8 Revalidation 8 The next step 8 Application form 9 2 | Chartered Status ‘Having a professionally recognised qualification will build my external credibility’ Elaine Baxter BSc PhD MRSC Procter & Gamble Elaine Baxter is a Senior Scientist at Procter & Gamble (P&G). Since joining the company, she has had roles in formulation, process and technology development in skin and shaving science. She graduated in 2001, before completing a PhD on synthetic inorganic chemistry of platinum dyes with applications in solar cells. Elaine is currently working towards Chartered Chemist status through the Professional Development Programme. Why do you want to achieve Chartered Chemist status? My role involves science communication with people such as dermatologists, academics and the media; having a professionally recognised qualification will build my external credibility with these professionals. How do you feel the programme has worked for you? Working towards achieving the attributes required for the CChem award has presented me with opportunities to share my industry knowledge and help others. -

Pauling-Linus.Pdf

NATIONAL ACADEMY OF SCIENCES L I N U S C A R L P A U L I N G 1901—1994 A Biographical Memoir by J A C K D. D UNITZ Any opinions expressed in this memoir are those of the author(s) and do not necessarily reflect the views of the National Academy of Sciences. Biographical Memoir COPYRIGHT 1997 NATIONAL ACADEMIES PRESS WASHINGTON D.C. LINUS CARL PAULING February 28, 1901–August 19, 1994 BY JACK D. DUNITZ INUS CARL PAULING was born in Portland, Oregon, on LFebruary 28, 1901, and died at his ranch at Big Sur, California, on August 19, 1994. In 1922 he married Ava Helen Miller (died 1981), who bore him four children: Linus Carl, Peter Jeffress, Linda Helen (Kamb), and Edward Crellin. Pauling is widely considered the greatest chemist of this century. Most scientists create a niche for themselves, an area where they feel secure, but Pauling had an enormously wide range of scientific interests: quantum mechanics, crys- tallography, mineralogy, structural chemistry, anesthesia, immunology, medicine, evolution. In all these fields and especially in the border regions between them, he saw where the problems lay, and, backed by his speedy assimilation of the essential facts and by his prodigious memory, he made distinctive and decisive contributions. He is best known, perhaps, for his insights into chemical bonding, for the discovery of the principal elements of protein secondary structure, the alpha-helix and the beta-sheet, and for the first identification of a molecular disease (sickle-cell ane- mia), but there are a multitude of other important contri- This biographical memoir was prepared for publication by both The Royal Society of London and the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America. -

The Molecular Monorail

RADBOUD UNIVERSITY NIJMEGEN RESEARCH PROPOSAL HONOURS ACADEMY FNWI The molecular monorail Authors: Robert BECKER Nadia ERKAMP Supervisor: Marieke GLAZENBURG Prof. Thomas BOLTJE Evert-Jan HEKKELMAN Lisanne SELLIES May 2017 Contents 1 Details 2 1.1 Applicants . .2 1.2 Supervisor . .2 1.3 Keywords . .2 1.4 Field of research . .2 2 Summaries 3 2.1 Scientific summary . .3 2.2 Public summary . .3 2.3 Samenvatting voor algemeen publiek . .3 3 Introduction 5 4 Background 8 4.1 The Feringa motor . .8 4.2 The ring molecule . .9 4.3 Threading of the track . 11 4.4 The track polymer . 12 5 Methods 14 5.1 Optical trapping . 14 5.2 Detection . 15 5.3 Synthesis . 16 5.3.1 Ring.................................... 16 5.3.2 Track . 17 6 Future applications 18 6.1 Further shrink down lab-on-a-chip approach . 18 6.2 Lab-on-a-chip approach in health care: Point-of-care testing (POCT) . 18 1 1 Details 1.1 Applicants Robert Becker - Biology Evert-Jan Hekkelman - Physics & Nadia Erkamp - Chemistry Mathematics Marieke Glazenburg - Physics Lisanne Sellies - Chemistry 1.2 Supervisor Name: Thomas Boltje Telephone: 024-3652331 Email: [email protected] Institute: Synthetic Organic Chemistry Radboud University Nijmegen 1.3 Keywords Nanomachine, Feringa, polymer, porphyrin, FRET 1.4 Field of research NWO division: Chemical Sciences [CW] Code Main field of research 13.20.00 Macromolecular chemistry, polymer chemistry Other fields of research 13.30.00 Organic chemistry 13.50.00 Physical chemistry 12.20.00 Nanophysics/technology 14.80.00 Nanotechnology 2 2 Summaries 2.1 Scientific summary In this proposal we present the design for a new kind of nanomachine. -

Robert Burns Woodward

The Life and Achievements of Robert Burns Woodward Long Literature Seminar July 13, 2009 Erika A. Crane “The structure known, but not yet accessible by synthesis, is to the chemist what the unclimbed mountain, the uncharted sea, the untilled field, the unreached planet, are to other men. The achievement of the objective in itself cannot but thrill all chemists, who even before they know the details of the journey can apprehend from their own experience the joys and elations, the disappointments and false hopes, the obstacles overcome, the frustrations subdued, which they experienced who traversed a road to the goal. The unique challenge which chemical synthesis provides for the creative imagination and the skilled hand ensures that it will endure as long as men write books, paint pictures, and fashion things which are beautiful, or practical, or both.” “Art and Science in the Synthesis of Organic Compounds: Retrospect and Prospect,” in Pointers and Pathways in Research (Bombay:CIBA of India, 1963). Robert Burns Woodward • Graduated from MIT with his Ph.D. in chemistry at the age of 20 Woodward taught by example and captivated • A tenured professor at Harvard by the age of 29 the young... “Woodward largely taught principles and values. He showed us by • Published 196 papers before his death at age example and precept that if anything is worth 62 doing, it should be done intelligently, intensely • Received 24 honorary degrees and passionately.” • Received 26 medals & awards including the -Daniel Kemp National Medal of Science in 1964, the Nobel Prize in 1965, and he was one of the first recipients of the Arthur C. -

Weak Functional Group Interactions Revealed Through Metal-Free Active Template Rotaxane Synthesis

ARTICLE https://doi.org/10.1038/s41467-020-14576-7 OPEN Weak functional group interactions revealed through metal-free active template rotaxane synthesis Chong Tian 1,2, Stephen D.P. Fielden 1,2, George F.S. Whitehead 1, Iñigo J. Vitorica-Yrezabal1 & David A. Leigh 1* 1234567890():,; Modest functional group interactions can play important roles in molecular recognition, catalysis and self-assembly. However, weakly associated binding motifs are often difficult to characterize. Here, we report on the metal-free active template synthesis of [2]rotaxanes in one step, up to 95% yield and >100:1 rotaxane:axle selectivity, from primary amines, crown ethers and a range of C=O, C=S, S(=O)2 and P=O electrophiles. In addition to being a simple and effective route to a broad range of rotaxanes, the strategy enables 1:1 interactions of crown ethers with various functional groups to be characterized in solution and the solid state, several of which are too weak — or are disfavored compared to other binding modes — to be observed in typical host–guest complexes. The approach may be broadly applicable to the kinetic stabilization and characterization of other weak functional group interactions. 1 Department of Chemistry, University of Manchester, Manchester M13 9PL, UK. 2These authors contributed equally: Chong Tian, Stephen D. P. Fielden. *email: [email protected] NATURE COMMUNICATIONS | (2020) 11:744 | https://doi.org/10.1038/s41467-020-14576-7 | www.nature.com/naturecommunications 1 ARTICLE NATURE COMMUNICATIONS | https://doi.org/10.1038/s41467-020-14576-7 he bulky axle end-groups of rotaxanes mechanically lock To explore the scope of this unexpected method of rotaxane Trings onto threads, preventing the dissociation of the synthesis, here we carry out a study of the reaction with a series of components even if the interactions between them are not related electrophiles. -

Multistep Synthesis of Complex Carbogenic Molecules

THE LOGIC OF CHEMICAL SYNTHESIS: MULTISTEP SYNTHESIS OF COMPLEX CARBOGENIC MOLECULES Nobel Lecture, December 8, 1990 by E LIAS J AMES C OREY Department of Chemistry, Harvard University, Cambridge, Massachusetts, USA Carbogens, members of the family of carbon-containing compounds, can exist in an infinite variety of compositions, forms and sizes. The naturally occurring carbogens, or organic substances as they are known more tradi- tionally, constitute the matter of all life on earth, and their science at the molecular level defines a fundamental language of that life. The chemical synthesis of these naturally occurring carbogens and many millions of unnatural carbogenic substances has been one of the major enterprises of science in this century. That fact is affirmed by the award of the Nobel Prize in Chemistry for 1990 for the “development of the theory and methodology of organic synthesis”. Chemical synthesis is uniquely positioned at the heart of chemistry, the central science, and its impact on our lives and society is all pervasive. For instance, many of today’s medicines are synthetic and many of tomorrow’s will be conceived and produced by synthetic chemists. To the field of synthetic chemistry belongs an array of responsibilities which are crucial for the future of mankind, not only with regard to the health, material and economic needs of our society, but also for the attainment of an understanding of matter, chemical change and life at the highest level of which the human mind is capable. The post World War II period encompassed remarkable achievement in chemical synthesis. In the first two decades of this period chemical syntheses were developed which could not have been anticipated in the earlier part of this century. -

Molecular Machines

Synthetic small molecules as machines: a chemistry perspective Professor Pradyut Ghosh Department of Inorganic Chemistry Indian Association for the Cultivation of Science 2A & 2B Raja S. C. Mullick Road, Kolkata 700032 E-mail: [email protected] 28th Mid-Year Meeting of Indian Academy of Sciences (IASc), Bengaluru, 1st July 2017 Feynman’s Dream on Molecular Machines Classic Talk given at the Meeting of the American Society of Physics in 1959 about the future of design and engineering at the molecular level The possibility of building small machines from atoms i.e. machines small enough to manufacture objects with atomic precision. Transcript of Talk : Caltech Eng. Sci. 1960, 23:5, 22–36. Feynman’s 1984 Visionary Lecture……. How small can you make machinery? Machines with dimensions on the nanometre scale. These already existed in nature. He gave bacterial flagella, corkscrew-shaped macromolecules as an example. Future vision – molecular machines will exist within 25–30 years. The aim of the lecture: To inspire the researchers in the audience, to get them to test the limits of what they believed possible. What neither Feynman, nor the researchers in the audience, knew at the time was that the first step towards molecular machinery had already been taken, but in a rather different way to that predicted by Feynman. What is that? 1953: Mechanical Bonds in Molecules Mid-20th century: Chemists were trying to build molecular chains in which ring-shaped molecules were linked together. The dream: To create mechanical bonds, where molecules are interlocked without the atoms interacting directly with each other. Frisch, H. -

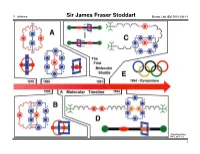

Sir James Fraser Stoddart Baran Lab GM 2010-08-14

Y. Ishihara Sir James Fraser Stoddart Baran Lab GM 2010-08-14 (The UCLA USJ, 2007, 20, 1–7.) 1 Y. Ishihara Sir James Fraser Stoddart Baran Lab GM 2010-08-14 (The UCLA USJ, 2007, 20, 1–7.) 2 Y. Ishihara Sir James Fraser Stoddart Baran Lab GM 2010-08-14 Professor Stoddart's publication list (also see his website for a 46-page publication list): - 9 textbooks and monographs - 13 patents "Chemistry is for people - 894 communications, papers and reviews (excluding book chapters, conference who like playing with Lego abstracts and work done before his independent career, the tally is about 770) and solving 3D puzzles […] - At age 68, he is still very active – 22 papers published in the year 2010, 8 months in! Work is just like playing - He has many publications in so many fields... with toys." - Journals with 10+ papers: JACS 75 Acta Crystallogr Sect C 26 ACIEE 67 JCSPT1 23 "There is a lot of room for ChemEurJ 62 EurJOC 19 creativity to be expressed JCSCC 51 ChemComm 15 in chemis try by someone TetLett 42 Carbohydr Res 12 who is bent on wanting to OrgLett 35 Pure and Appl Chem 11 be inventive and make JOC 28 discoveries." - High-profile general science journals: Nature 4 Science 5 PNAS 8 - Reviews: AccChemRes 8 ChemRev 4 ChemSocRev 6 - Uncommon venues of publication for British or American scientists: Coll. Czechoslovak Chem. Comm. 5 Mendeleev Communications 2 Israel Journal of Chemistry 5 Recueil des Trav. Chim. des Pays-Bas 2 Canadian Journal of Chemistry 4 Actualité chimique 1 Bibliography (also see his website, http://stoddart.northwestern.edu/ , for a 56-page CV): Chemistry – An Asian Journal 3 Bulletin of the Chem.