World Creativity Summit 2008 Taipei Report

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Urbandignityvolume9 2014.Pdf

Journal of Urban Culture Research Volume 9 Jul - Dec 2014 Published jointly by Chulalongkorn University, Thailand and Osaka City University, Japan The views and opinions expressed herein are those of the individual author(s) BOEEPOPUOFDFTTBSJMZSFÏFDUUIFQPMJDJFTPSPQJOJPOTPGUIFJournal (JUCR), it editors and staff, Chulalongkorn University, or Osaka City University. Authors authorize the JUCR to publish their materials both in print and online while retaining their full individual copyright. The copyright of JUCR volumes is retained by Chulalongkorn University. © 2014 BY CHULALONGKORN UNIVERSITY ISSN 2228 – 8279 (Print) ISSN 2408 – 1213 (Online) JUCR is listed in the Thai-Journal Citation Index – TCI 5IJTQVCMJDBUJPOJTBOPOQSPÎUFEVDBUJPOBMSFTFBSDIKPVSOBMOPUGPSTBMF Journal of Urban Culture Research Executive Director Suppakorn Disatapandhu, Chulalongkorn University, Thailand Editor in Chief Kjell Skyllstad, University of Oslo, Norway International Editor Alan Kinear, Chulalongkorn University, Thailand Contributing Editors Bussakorn Binson, Chulalongkorn University, Thailand Shin Nakagawa, Osaka City University, Japan Managing Editor Pornprapit Phoasavadi, Chulalongkorn University, Thailand Editorial Board Frances Anderson, College of Charleston, USA Bussakorn Binson, Chulalongkorn University, Thailand Naraphong Charassri, Chulalongkorn University, Thailand Dan Baron Cohen, Institute of Transformance: Culture and Education, Brazil Gavin Douglas, University of North Carolina, USA Made Mantle Hood, University of Putra, Malaysia Geir Johnson, Music -

PTW14-Program.Pdf

performing the world 2014 Participant Countries Argentina Denmark Nepal Romania Australia England Netherlands Scotland Austria Ghana Nicaragua Serbia Bangladesh Greece Nigeria South Africa Norway Botswana India Taiwan The Sultanate Brazil Israel of Oman Uganda Canada Italy Pakistan United States Chile Japan Peru Colombia Mexico Philippines (as of 10/21/14) how shall we become? NEW YORK CITY performing the world 2014 Contents Greetings ...............................................................page 3 Schedule ................................................................page 11 Session Descriptions ...........................................page 19 Visitors Guide .......................................................page 51 Thanks ....................................................................page 59 Welcome from the All Stars Project On behalf of the All Stars Project’s board of directors, staff, donors, young people Note: You will find presenter bios online at www.performingtheworld.org and volunteers, I welcome you to Performing the World 2014 and to the All Stars Project’s performing arts and development center. We are proud to be co- sponsoring this extraordinary international gathering. “How Shall We Become?” is a question that permeates everything we do at the All Stars. How shall the people we work with —young people and adults, from corporate boardrooms to inner-city communities — become deeper, broader, more worldly and more developed? We can never know in advance what we shall become, but we believe that how we become — through play and performance — gives us all the best chance for development. performing We look forward to these three days of asking “How Shall We Become?” with all of you. We hope you enjoy our theatres, our volunteer staff, New York City — and “becoming” together. the Warm regards, world 2014 Gabrielle L. Kurlander President and CEO All Stars Project, Inc. -

Information to Users

INFORMATION TO USERS This manuscript has been reproduced from the microfilm master. UMI films the text directly from the original or copy submitted. Thus, some thesis and dissertation copies are in typewriter face, while others may be from any type of computer printer. The quality of this reproduction is dependent upon the quality of the copy submitted. Broken or indistinct print, colored or poor quality illustrations and photographs, print bleedthrough, substandard margins, and improper alignment can adversely afreet reproductioiL In the unlikely event that the author did not send UMI a complete manuscript and there are missing pages, these will be noted. Also, if unauthorized copyright material had to be removed, a note will indicate the deletion. Oversize materials (e.g., maps, drawings, charts) are reproduced by sectioning the original, beginning at the upper left-hand comer and continuing from left to right in equal sections with small overlaps. Each orignal is also photographed in one exposure and is included in reduced form at the back of the book. Photographs included in the original manuscript have been reproduced xerographically in this copy. Higher quality 6” x 9” black and white photographic prints are available for any photographs or illustrations appearing in this copy for an additional charge. Contact UMI directly to order UMI A Bell & Howell Information Company 300 North Zeeb Road, Ann Arbor MI 48106-1346 USA 313/761-4700 800/521-0600 AMBIGUITY AND DECEPTION IN THE COVERT TEXTS OF SOUTH AFRICAN THEATRE: 1976-1996 DISSERTATION Presented in Partial Fulfilment of the Requirements for the Degree Doctor of Philosophy in the Graduate School of The Ohio State University By Allan John Munro, M.A., H.D.E. -

Completed and Resubmitted Within the Time Frame Speci!Ed

Journal of Urban Culture Research !"#$%&'(#)*'+#$&,+ Suppakorn Disatapandhu, !"#$%$&'()&*'+,'-./*0-123+4"%-$%'5 !-'&,+)'.)/0'#1 Bussakorn Binson, !"#$%$&'()&*'+,'-./*0-123+4"%-$%'5 2.&#+.3&',.34)!-'&,+ Alan Kinear, !"#$%$&'()&*'+,'-./*0-123+4"%-$%'5 /,.&+'5%&'.6)!-'&,+ Kjell Skyllstad, ,'-./*0-12+&6+70$&3+8&*9%2 73.36'.6)!-'&,+ Pornprapit Phoasavadi, !"#$%$&'()&*'+,'-./*0-123+4"%-$%'5 !-'&,+'34)8,3+- Frances Anderson, !&$$/(/+&6+!"%*$/01&'3+,:; Bussakorn Binson, !"#$%$&'()&*'+,'-./*0-123+4"%-$%'5 Naraphong Charassri, !"#$%$&'()&*'+,'-./*0-123+4"%-$%'5 Dan Baron Cohen, <'01-1#1/+&6+4*%'06&*=%'>/?+!#$1#*/+%'5+@5#>%1-&'3+A*%B-$ Gavin Douglas, ,'-./*0-12+&6+8&*1"+!%*&$-'%3+,:; Geir Johnson, C#0->+<'6&*=%1-&'+!/'1*/+C<!D4*%'0E&0-1-&'3+8&*9%2 Zuzana Jurkova, !"%*$/0+,'-./*0-123+!B/>"+F/E#G$-> Prapon Kumjim, !"#$%$&'()&*'+,'-./*0-123+4"%-$%'5 Le Van Toan,+8%1-&'%$+;>%5/=2+&6+C#0->3+H-/1'%= Shin Nakagawa, 70%)%+!-12+,'-./*0-123+I%E%' Svanibor Pettan, ,'-./*0-12+&6+JK#G$K%'%3+:$&./'-% Leon Stefanija,+,'-./*0-12+&6+JK#G$K%'%3+:$&./'-% Deborah Stevenson,+,'-./*0-12+&6+L/01/*'+:25'/23+;#01*%$-% Pornsanong Vongsingthong, !"#$%$&'()&*'+,'-./*0-123+4"%-$%'5 9#5:3;&#+ Alan Kinear <3=,%&)>)*#;'6. Alan Kinear3+!&./*+G2 Nawarat Sitthimongkolchai /,?=+'60& It is a condition of publication that the Journal assigns copyright or licenses the publication rights in their articles, including abstracts, to the authors. /,.&3$&)2.1,+:3&',.@ Journal of Urban Culture Research Faculty of Fine and Applied Arts Chulalongkorn University Payathai Road, Pathumwan Bangkok, Thailand 10330 Voice/Fax: 662-218-4582 Email: [email protected] Website: www.cujucr.com This publication is a non-pro!t educational research journal not for sale. -

February 26, 2011

Daniel Roche (480) 938-7755 [email protected] www.daniel-roche.com Degrees and Certifications Master of Fine Arts, Creative Writing, San Francisco State University 2012 Concentration in Playwriting • Thesis: “Virginia Woolf’s Mrs. Dalloway” Advisor: Roy Conboy Second Thesis Reader: Brian Thorstensan Master of Arts, English San Francisco State University 2011 Concentration in Creative Writing, Poetry • Thesis: “The Paperwork Rebuttal” Advisor: Camille Dungy Second Thesis Reader: Maxine Chernoff Bachelor of Arts, English Literature Arizona State University 2004 TEFL Certification (Teaching English as a International TEFL and TESOL 2014 Foreign Language) Training (120 hours) Honors and Awards Teacher Ranked as Outstanding, University of Illinois at Urbana Champaign Dec. 2019 Playwright in Residence, Catwalk Institute Nov. 2019 Best Screenplay Nominee, Sparrow Film Project Dec. 2018 Instructor of the Year, Guangdong Peizheng College May 2014 Finalist, DIAGRAM Award for Innovative Fiction March 2012 Finalist, Platypus Prize for Innovative Fiction April 2012 Honorable Mention, Robert Browning Society Award for Dramatic Monologues Dec. 2011 Honorable Mention, Writer’s Digest International Playwriting Contest May 2004 Roche, Daniel - 1 Academic Teaching Experience LECTURER, Department of English University of Illinois, Urbana Champaign August 2019 - Present Courses: BTW 250, Principles of Business and Technical Writing DANC 451, Social Impact Through Motion Media Arts and Technology (Assistant to John Toenjas) Volunteer: Robotics, Animation, and Dance Lab (RAD Lab) • Instruct students in the fundamentals of business and technical writing by emphasizing the importance of target audience, format, and writing multiple drafts. • Lecture on narrative structure as applied to film and game design. • Introduce the fundamentals of Unity Game Engine and C# programming for the development of performance experiences. -

Completely Recall, with the Help of Books Or People (Ozawa, Arakida, and Endo 1999:331)

Journal of Urban Culture Research Volume 13 Jul - Dec 2016 Published jointly by Chulalongkorn University, Thailand and Osaka City University, Japan The views and opinions expressed herein are those of the individual author(s) and do not necessarily re!ect the policies or opinions of the Journal (JUCR), it editors and staff, Chulalongkorn University, or Osaka City University. Authors authorize the JUCR to publish their materials both in print and online while retaining their full individual copyright. The copyright of JUCR volumes is retained by Chulalongkorn University. © 2016 BY CHULALONGKORN UNIVERSITY ISSN 2228 – 8279 (Print) ISSN 2408 – 1213 (Online) JUCR is listed in the following citation databases Thomson Reuters Web of Science Core Collection, Emerging Sources Citation Index – ESCI Norwegian Register for Scienti"c Journals, Series and Publishers – NSD Thai-Journal Citation Index – TCI Asean Citation Index – ACI JUCR is archived at United States Library of Congress Cornell University Library – John M. Echols Collection on Southeast Asia This publication is a non-pro!t educational research journal not for sale. Journal of Urban Culture Research Executive Director Suppakorn Disatapandhu, Chulalongkorn University, Thailand Editor in Chief Kjell Skyllstad, University of Oslo, Norway International Editor Alan Kinear, Chulalongkorn University, Thailand Contributing Editors Bussakorn Binson, Chulalongkorn University, Thailand Shin Nakagawa, Osaka City University, Japan Managing Editor Pornprapit Phoasavadi, Chulalongkorn University, Thailand -

A Typology in Isfahan, Iran

Journal of Urban Culture Research Volume 22 Jan - Jun 2021 Published jointly by Chulalongkorn University, Thailand and Osaka City University, Japan The views and opinions expressed herein are those of the individual author(s) and do not necessarily re!ect the policies or opinions of the Journal (JUCR), its editors and staff, Chulalongkorn University, or Osaka City University. Authors authorize the JUCR to publish their materials both in print and online while retaining their full individual copyright. The copyright of JUCR volumes is retained by Chulalongkorn University. © 2021 BY CHULALONGKORN UNIVERSITY ISSN 2228 – 8279 (Print) ISSN 2408 – 1213 (Online) JUCR is listed in the following citation databases Thomson Reuters Web of Science Core Collection, Emerging Sources Citation Index – ESCI Norwegian Register for Scienti"c Journals, Series and Publishers – NSD Thai-Journal Citation Index – TCI Asean Citation Index – ACI Scopus – Elsevier JUCR is archived at United States Library of Congress Cornell University Library – John M. Echols Collection on Southeast Asia Publishing statistics JUCR has published 155 articles from 35 countries throughout its 22 volume history. This publication is a non-pro!t educational research journal not for sale Journal of Urban Culture Research Executive Director & Editor in Chief Bussakorn Binson, Chulalongkorn University, Thailand Associate Editor Alan Kinear, Chulalongkorn University, Thailand Contributing Editor Shin Nakagawa, Osaka City University, Japan Managing Editor Pornprapit Phoasavadi, Chulalongkorn -

Version of the Programme

Sunday 6 August Monday 7 August Tuesday 8 August Wednesday 9 August Thursday 10 August Friday 11 August Saturday 12 August 9h00 C.9 Parallel sessions and symposia: C.13 Parallel sessions and C.5 Parallel sessions and symposia individual paper proposals symposia: individual paper A.4 Keynote address Reports from the preparatory S.II.4 (1); proposals Tanella Boni, "Penser au Féminin à conferences S.II.6; S.III.8 ; S.VI.15; S.VI.16; S.I.3; S.II.4(2); S.IV.9 (2); partir de l'Afrique" I.4; II.4; IV.3; V.6; VI.12; VI.28; VI.29; 9h-10h S.VI.17; S.VI.20 S.IV.10; S.V.12; S.VI.18 VI.32 9h-10h 9h-10h 10h00 9h-10h30 Coffee Break Coffee Break Coffee Break 9h-10h30 P.V Plenary session - History, A.5 Keynote address A.6 Keynote address UNESCO-CIPSH Memory and Politics Coffee Break Souleymane Bachir Diagne, Kumie Inose, "The Role of Humanities Wrap-Up Meeting CIPSH General Moderator: Laurent Tissot Coffee Break "Philosophy in the Face of Tribalism" in a World Full of Violence" (Closed) Assembly Speakers include: Chantal Grell, A.3 Keynote address 10h15-11h15 10h15-11h15 Salle des Professeurs Salle des Mariët Westermann, Chris Carey, 11h00 Robert Kahn, "Capturing the Past in Professeurs Chaterine Jami the Present: and Making it Accessible" 10h45-11h45 9h-13h 10h15-11h45 P.VI Plenary Session - New Contexts P.II Plenary session - Cultural for the Humanities P.VIII CIPSH plenary session Diversity Moderator: Hsiung Ping-Chen Moderator: Adama Samassekou Speakers include: Rosi Braidotti, 12h00 11h-13h P.IV Plenary Sessions - Cultural Heritage Speakers include: -

Intercultural Drama Ethnic Minority Children and the Arts Drama And

The Journal of National Drama Volume 8 No 2 Summer 2001 DONE FORUMrama MANY VOICES Intercultural drama Ethnic minority children and the arts Drama and digital technology Desenterrando o futuro Spirit Youth Theatre Festival £7.50 Cover design: Neil Baird, from an original photograph by Mark Mortimer Drama Magazine is the journal of National Drama The Journal of National Drama Volume 8 No 2 Summer 2001 DONE FORUMrama MANY VOICES Drama one forum many voices Intercultural drama Ethnic minority children and the arts Drama enables Drama educators and practi- Drama and digital technology tioners nationally and internationally to share theory Desenterrando o futuro Spirit Youth Theatre Festival and practice, debate key issues, publish research, engage in critical analysis and express personal opin- ions Drama is committed to the promotion, support and development of new writers Drama is an equal opportunities publication in line with National Drama policy £7.50 Editor Chris Lawrence Design and production Dokumenta Drama Editorial Board ONLINE Judith Ackroyd, Win Bayliss, Chris Lawrence, Marie-Jeanne McNaughton, Ned Milne, John Rainer. Ex officio: Pam Bowell and Jan Macdonald. The Drama magazine website Editorial Our World Wide Website Chris Lawrence, ND publications, Drama, at Central School of Speech and Drama, contains news items, Eton Avenue, London NW3 3HY, United Kingdom. publications, reviews and Telephone: 020 7722 4730. EMail: [email protected] much more. Advertising You can access the pages for contact Gabriela Lerner Drama Magazine advertising free, download information, Dokumenta, The Coppice, Higher Coombe, Shaftesbury SP7 9LR Telephone: 01747 858801, Fax: 01747 858803 make comments, and link to EMail: [email protected] other related internet sites. -

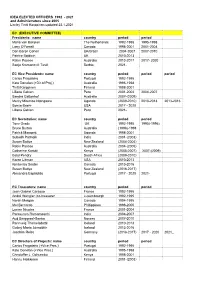

IDEA ELECTED OFFICERS 1992 - 2021 and Administrators Since 2005 List by Tintti Karppinen Updated 23.1.2021

IDEA ELECTED OFFICERS 1992 - 2021 and Administrators since 2005 List by Tintti Karppinen updated 23.1.2021 EC (EXECUTIVE COMMITTEE) Presidents: name country period period Maria van Bakelen The Netherlands 1992-1995 1995-1998 Larry O'Farrell Canada 1998-2001 2001-2004 Dan Baron Cohen UK/Brazil 2004-2007 2007-2010 Patrice Baldwin UK 2010-2013 Robin Pascoe Australia 2013-2017 2017- 2020 Sanja Krsmanović Tasić Serbia 2021- EC Vice Presidents: name country period period period Carlos Fragateiro Portugal 1992-1995 Kate Donelan (+Dir.of Proj.) Australia 1995-1998 Tintti Karppinen Finland 1998-2001 Liliana Galvan Peru 2001-2004 2004-2007 Sandra Gattenhof Australia 2007-(2009) Mercy Mirembe Ntangaare Uganda (2009-2010) 2010-2013 2013-2016 Sonya Baehr USA 2017 - 2020 Liliana Galvan Peru 2021- EC Secretaries: name country period period Tony Grady UK 1992-1995 1995(-1996) Bruce Burton Australia (1996)-1998 Patrick Mangeni, Uganda 1998-2001 Subodh Pattnaik India 2001-(2003) Susan Battye New Zealand (2004-2004) Robin Pascoe Australia 2004-(2005) Catherine Kariuki Kenya (2005-2007) 2007-(2009) Betsi Pendry South Africa (2009-2010) Karen Libman USA 2010-2013 Kimberley Snider Canada 2013-2016 Susan Battye New Zealand (2016-2017) Alexandra Espiridião Portugal 2017 - 2020 2021- EC Treasurers: name country period period Jean Gabriel Carasso France 1992-1995 André Wengler (co-treasurer Luxembourgh 1992-1995 Norah Morgan Canada 1994-1995 Mel Bernardo Phillippines 1998-2000 Lucien Nicolas France 2001-2004 Parasuram Ramamoorthi India 2004-2007 Aud Berggraaf-Saebo Norway 2007-2010 Rannveig Thorkelsdottir Iceland 2010-2013 Guðný María Jónsdóttir Iceland 2013-2016 Joachim Reiss Germany (2016-2017) 2017 - 2020 2021_ EC Directors of Projects: name country period period Carlos Fragateiro (+Vice Pres.) Portugal 1992-1995 Kate Donelan (+Vice Pres.) Australia 1995-1998 Christoffer J. -

Presenters Hierarchy, All of the Permanent Staff Will Make the Camylla Alves (Marabá, Brazil) Is a Dancer, Same Salary- $300 Dollars a Month

performing the world 2014 Patch Adams (Urbana, IL, USA) is best known with homeless adults in a project (1999) that offered for his work as a medical doctor and clown and is also classes in different areas including art education and a social activist who has devoted 44 years to changing conversation groups. This project offered support for America’s health care system. Patch is the founder its team (in a partnership with Familiae Institute) on of the Gesundheit Institute in West Virginia, whose any issues the workers wanted to explore. Later she purpose is to create a fuller modern hospital addressing worked for the City of São Paulo, supervising projects all the problems of healthcare delivery in one model. for kids at after-school care programs. She is currently The hospital is designed to eliminate 90% of the cost enjoying a comeback to dance phase performing with of care where all the permanent staff live together in Detroit-based dance companies, teaching samba and a communal eco-village with the hospital, eliminating learning how performing is developing and how she 85% of their environmental footprint. To eliminate shall become! Presenters hierarchy, all of the permanent staff will make the Camylla Alves (Marabá, Brazil) is a dancer, same salary- $300 dollars a month. The hospital will community arts educator, cultural producer and not carry malpractice insurance nor accept any health founder-coordinator of the AfroMundi Dance Company insurance. It will have a teaching center attached to the in the Rivers of Meeting (Rios de Encontro) project hospital with a wide variety of courses. -

Arts, Humanities, Social Sciences and Performing

ARTS, HUMANITIES, SOCIAL SCIENCES AND PERFORMING ARTS 2021 GRADUATE COURSE GUIDE The Monash Arts experience Your success starts here 2 Flexibility 3 STUDY Industry engagement 5 Elite facilities 5 Ready to go global? 6 AT MONASH – Embrace immersive learning 7 Our programs Master of Applied Linguistics 10 AUSTRALIA’S Master of Bioethics 12 Master of Communications and Media Studies 14 Master of Cultural and LARGEST Creative Industries 16 Master of Environment and Sustainability 18 Graduate Certificate of UNIVERSITY Family Violence Prevention 20 Graduate Diploma of Family Violence Prevention 21 Graduate Certificate of Gender, Peace and Security 22 Master of International Development Practice 24 Master of International Relations 26 Master of International Sustainable Tourism Management 28 Master of Interpreting and Translation Studies 30 Master of Journalism 32 Master of Public Policy 34 Master of Strategic Communications Management 36 Bachelor’s/Master’s program 38 Graduate research degrees 40 Important information Eligibility, FAQs and fees 41 Location Duration Intakes Note: The entry requirements listed in the Fast Facts are for domestic students only. Please visit monash.edu/study for detailed entry requirements. If you love big ideas, vibrant cities and once-in-a-lifetime experiences, you belong at Monash Arts. Monash University spans multiple campuses in Melbourne and is the Melbourne is also marked as a UNESCO City of Literature and features largest university in Australia with more international campuses than a year-round program of celebrated festivals and events at its leading any other Australian university. It’s dedicated to transcending traditional institutions and regional attractions. Get ready to find your tribe within boundaries and achieving an impact on communities worldwide.