2016: Accountability for the Victims and the Right to Truth

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Basra: Strategic Dilemmas and Force Options

CASE STUDY NO. 8 COMPLEX OPERATIONS CASE STUDIES SERIES Basra: Strategic Dilemmas and Force Options John Hodgson The Pennsylvania State University KAREN GUTTIERI SERIES EDITOR Naval Postgraduate School COMPLEX OPERATIONS CASE STUDIES SERIES Complex operations encompass stability, security, transition and recon- struction, and counterinsurgency operations and operations consisting of irregular warfare (United States Public Law No 417, 2008). Stability opera- tions frameworks engage many disciplines to achieve their goals, including establishment of safe and secure environments, the rule of law, social well- being, stable governance, and sustainable economy. A comprehensive approach to complex operations involves many elements—governmental and nongovernmental, public and private—of the international community or a “whole of community” effort, as well as engagement by many different components of government agencies, or a “whole of government” approach. Taking note of these requirements, a number of studies called for incentives to grow the field of capable scholars and practitioners, and the development of resources for educators, students and practitioners. A 2008 United States Institute of Peace study titled “Sharing the Space” specifically noted the need for case studies and lessons. Gabriel Marcella and Stephen Fought argued for a case-based approach to teaching complex operations in the pages of Joint Forces Quarterly, noting “Case studies force students into the problem; they put a face on history and bring life to theory.” We developed -

Report on the Protection of Civilians in the Armed Conflict in Iraq

HUMAN RIGHTS UNAMI Office of the United Nations United Nations Assistance Mission High Commissioner for for Iraq – Human Rights Office Human Rights Report on the Protection of Civilians in the Armed Conflict in Iraq: 11 December 2014 – 30 April 2015 “The United Nations has serious concerns about the thousands of civilians, including women and children, who remain captive by ISIL or remain in areas under the control of ISIL or where armed conflict is taking place. I am particularly concerned about the toll that acts of terrorism continue to take on ordinary Iraqi people. Iraq, and the international community must do more to ensure that the victims of these violations are given appropriate care and protection - and that any individual who has perpetrated crimes or violations is held accountable according to law.” − Mr. Ján Kubiš Special Representative of the United Nations Secretary-General in Iraq, 12 June 2015, Baghdad “Civilians continue to be the primary victims of the ongoing armed conflict in Iraq - and are being subjected to human rights violations and abuses on a daily basis, particularly at the hands of the so-called Islamic State of Iraq and the Levant. Ensuring accountability for these crimes and violations will be paramount if the Government is to ensure justice for the victims and is to restore trust between communities. It is also important to send a clear message that crimes such as these will not go unpunished’’ - Mr. Zeid Ra'ad Al Hussein United Nations High Commissioner for Human Rights, 12 June 2015, Geneva Contents Summary ...................................................................................................................................... i Introduction ................................................................................................................................ 1 Methodology .............................................................................................................................. -

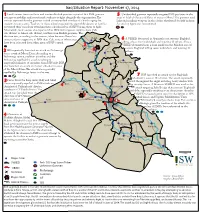

2014-11-17 Situation Report

Iraq Situation Report: November 17, 2014 1 Local sources from southern and western Kirkuk province reported that ISIS gunmen 5 Unidentied gunmen reportedly targeted ISIS positions in the attempt to mobilize and recruit male students to ght alongside the organization. e areas of Islah al-Zerai and Refai of western Mosul. e gunmen used sources reported that the gunmen visited an unspecied number of schools urging the light and medium weapons in the clashes that lasted for half an hour. students to carry arms. Teachers in these schools rejected this step while dozens of families A causality gure was not reported. prevented their sons from attending their schools in fear of ISIS forcing them to ght. Meanwhile, local sources also reported that ISIS shifted power supplies from Zab sub-district to Abassi sub-district, southwestern Kirkuk province. is decision was, according to the sources, taken because Abassi has Dahuk 6 more residents supportive of ISIS than Zab, some of whom may A VBIED detonated in Amiriyah area, western Baghdad, have been relocated from other areas of ISIS control. killing at least four individuals and injuring 13 others. Also, a Mosul2 Dam VBIED detonated near a local market in the Mashtal area of 2 5 eastern Baghdad killing seven individuals and injuring 22 ISIS reportedly launched an attack on Peshmerga Mosul Arbil others. forces south of Mosul Dam. According to a Peshmerga source, coalition airstrikes and the Peshmerga repelled the attack resulting in As Sulaymaniyah unspecied number of casualties from ISIS side. ISIS also launched an attack on Zumar sub-district, west Kirkuk of the Mosul Dam. -

Iraq Protection Cluster

Iraq Protection Cluster: Anbar Returnee Profile - March 2017 24 April 2017 Amiriyat Al- Protection Concerns Ramadi Heet Falluja/Garma Haditha Rutba Khaldiyah High Fallujah Reported Violations of principles relating to return movements (including non-discrimination in the right of return, as well as voluntariness, safety and dignity of return movements) Medium Security incidents resulting in death/injury in return area (including assault, murder, conflict-related casualties) Explosive Remnants of War (ERW)/ Improvised Explosive Device (IED) contamination in return area by District by Low Reported Rights violations by state or non-state military/security actors (including abduction, arbitrary arrest/detention, disproportionate restrictions on freedom of movement) Protection Risk Matrix Risk Protection Concerns relating to inter-communal relations and social cohesion MODM Returnee Figures Returnee Families (Registered and non-registered) District Families Falluja 53,218 Ramadi 82,242 Ramadi 51,293 Falluja/Garma 48,557 Ru'ua Heet 11,321 Heet 19,101 Haditha Haditha 3,936 Rutba 2,356 Ka'im Haditha 2,147 Heet 35,600 Baghdad 18,056 Rutba 1,825 Ana 31,299 Anbar 79,211 22,640 Anbar Displacements Erbil Ramadi 14,331 and Returns Falluja 13,341 Total Families Still Kirkuk 8,729 Displaced 12,472 Sulaymaniyah Total Families Rutba 6,500 Returned 4,440 Other 283 759 Babylon 474 IDP Information Center: 22% of calls received from Anbar were from returnees. The most popular issues flagged: 43% Governmental issues (grants, compensation on damaged properties, ..etc) 29% Cash assistance Data Sources: Disclaimer: 14% Other issues * IOM-DTM as of 30 March 2017 The boundaries and names shown and the designations used on this map * MoDM 18 April 2017 do not imply official endorsement or acceptance by the United Nations. -

UM AL-IRAQ (THE DATE PALM TREE) the Life and Work of Dr

UM AL-IRAQ (THE DATE PALM TREE) The Life and Work of Dr. Rashad Zaydan of Iraq By Nikki Lyn Pugh, Peace Writer Edited by Kaitlin Barker Davis 2011 Women PeaceMakers Program Made possible by the Fred J. Hansen Foundation *This material is copyrighted by the Joan B. Kroc Institute for Peace & Justice. For permission to cite, contact [email protected], with “Women PeaceMakers – Narrative Permissions” in the subject line. UM AL-IRAQ (THE DATE PALM TREE) ZAYDAN – IRAQ TABLE OF CONTENTS I. A Note to the Reader …………………………………………………………. 4 II. About the Women PeaceMakers Program …………………………………… 4 III. Biography of a Woman PeaceMaker — Dr. Rashad Zaydan ….……………… 5 IV. Conflict History — Iraq………………………………………………………… 7 V. Map — Iraq ……………………………………………………………………. 14 VI. Integrated Timeline — Political Developments and Personal History ………… 15 VII. Dedication …………………………………………………………………….. 22 VIII. Narrative Stories of the Life and Work of Dr. Rashad Zaydan 23 ُ UM AL-IRAQ 24 ُّ ُّ ُّ أمُّ ُّالعُّــ راق ُُُُُّّّّّ ُُُُُُُُُّّّّّّّّّ ّأولُّث ُّمَرَةُُُُُّّّّّ FIRST FRUIT 25 ُُُُّّّّالنُّ ـــشــأْة I. GROWING UP a. The Dawn’s Prayer …………………………………………………………. 26 b. Memories of Al Mansur ……………………………………………..……… II. MEHARAB AL NOOR/TEMPLES OF LIGHT 29 م ُحــرابُّالنّـــــور c. Beauty in Diversity …………………………………………………………. 31 d. The Day of Ashura ………………………………………………………… 32 e. Summer School ……………………………………………………………. 34 f. The First Spark …………………………………………………………….. 35 g. A Place for Prayer …………………………………………………………. 37 h. Postscript: The Most Advanced Degree ……………………………………. 39 ُُُُّّّّالحـــــربُّ والعقوباتُّ)الحصار(ُُُُّّّّ III. WAR AND SANCTIONS 42 َ ُ ُ ّ i. The Meaning of Marriage ………….………………………………………. 44 j. Baiji ………….……………………………………….……………………. 45 k. Wishing for Stability …………………….…………………………………. 46 l. Kuwait………………….………………………………………………….. 49 m. The Charity Clinic ………….……………………………………………… n. Postscript: The Empty House ………….………………………………….. 51 52 ا لُّحـــــــتـــــــﻻل IV. -

Why They Died Civilian Casualties in Lebanon During the 2006 War

September 2007 Volume 19, No. 5(E) Why They Died Civilian Casualties in Lebanon during the 2006 War Map: Administrative Divisions of Lebanon .............................................................................1 Map: Southern Lebanon ....................................................................................................... 2 Map: Northern Lebanon ........................................................................................................ 3 I. Executive Summary ........................................................................................................... 4 Israeli Policies Contributing to the Civilian Death Toll ....................................................... 6 Hezbollah Conduct During the War .................................................................................. 14 Summary of Methodology and Errors Corrected ............................................................... 17 II. Recommendations........................................................................................................ 20 III. Methodology................................................................................................................ 23 IV. Legal Standards Applicable to the Conflict......................................................................31 A. Applicable International Law ....................................................................................... 31 B. Protections for Civilians and Civilian Objects ...............................................................33 -

Mosul After the Battle

Mosul after the Battle Reparations for civilian harm and the future of Ninewa © Ceasefire Centre for Civilian Rights and Minority Rights Group International January 2020 Cover photo: This report has been produced with the financial assistance of the Swiss Federal De- A woman peeks out of a gate partment of Foreign Affairs and the European Union. The contents of this report are peppered with bullet marks after fighting between the Iraqi Army the sole responsibility of the publishers and can under no circumstances be regarded and ISIS militants in Al-Qadisiyah as reflecting the position of the Swiss FDFA or the European Union. district, Mosul, Iraq. © Iva Zimova/Panos This report was written by Khaled Zaza and Élise Steiner of Zaza Consulting, Mariam Bilikhodze and Dr. Mahmood Azzo Hamdow of the Faculty of Political Sci- ence, University of Mosul. Special thanks to Dr. Tine Gade for research support and review of the report. Ceasefire Centre for Civilian Rights The Ceasefire Centre for Civilian Rights is a new initiative to develop ‘civilian-led monitoring’ of violations of international humanitarian law or human rights, to pursue legal and political accountability for those responsible for such violations, and to develop the practice of civilian rights. The Ceasefire Centre for Civilian Rights is registered as a charity and a company limited by guarantee under English law; charity no: 1160083, company no: 9069133. Minority Rights Group International MRG is an NGO working to secure the rights of ethnic, religious and linguistic minorities and indigenous peoples worldwide, and to promote cooperation and understanding between communities. MRG works with over 150 partner orga- nizations in nearly 50 countries. -

Iraq SITREP 2015-5-22

Iraq Situation Report: July 07 - 08, 2015 1 On July 6, Iraqi Army (IA) and Counter-Terrorism Service (CTS) reinforcements arrived in 6 On July 6, the DoD reported one airstrike “near Baiji.” On July 7, one SVBIED Barwana sub-district, south of Haditha. On July 7, Prime Minister (PM) Abadi ordered the exploded in the Baiji Souq area in Baiji district, and two SVBIEDs exploded in the Sakak deployment of SWAT reinforcements to Haditha. Also on July 7, Iraqi Security Forces (ISF) and area west of Baiji, killing ten IA and “Popular Mobilization” members and wounding over tribal ghters, reportedly supported by Iraqi and U.S.-led Coalition air support, attacked ISIS in 30. Federal Police (FP) and “Popular Mobilization” forces repelled an attack by ISIS at Barwana and Alus sub-districts, south of Haditha, and destroyed two SVBIEDs in al-Sakran area, al-Fatha, northeast of Baiji, killing 20 ISIS ghters. On July 8, IA and “Popular Mobili- northeast of Haditha, before they reached their targets. Albu Nimr and Albu Mahal tribal ghters zation” reinforcements reportedly arrived in Baiji. Clashes reportedly continue in the Baiji later repelled a counterattack by ISIS against Barwana. IA Aviation and U.S.-led Coalition Souq area of Baiji and in the Sakak area, west of Baiji. IA Aviation and the U.S.-led airstrikes also reportedly destroyed an ISIS convoy heading from Baiji to Barwana. Between July 6 Coalition conducted airstrikes on al-Siniya and al-Sukaria, west of Baiji and on the and 7, the DoD reported eight airstrikes “near Haditha.” On July 8, ISF and tribal ghters repelled petrochemical plant, north of Baiji. -

Weekly Explosive Incidents Flas

iMMAP - Humanitarian Access Response Weekly Explosive Incidents Flash News (23 - 29 APR 2020) 78 14 22 9 0 INCIDENTS PEOPLE KILLED PEOPLE INJURED EXPLOSIONS AIRSTRIKES DIYALA GOVERNORATE NINEWA GOVERNORATE ISIS 23/APR/2020 Security Forces 23/APR/2020 Four mortar shells landed in Abu Karma village in Al-Ibarra subdistrict, northeast of Diyala. Destroyed an ISIS hideout, killing three insurgents and seized 3 kilograms of C4 and other explosive materials, west of Mosul. ISIS 23/APR/2020 Attacked a security checkpoint, killing two Tribal Mobilization Forces members and Popular Mobilization Forces 23/APR/2020 injuring another in Tanira area, north of Muqdadiya district. Halted an ISIS infiltration attempt in Al-Hader district, southwest of Mosul. ISIS 24/APR/2020 Military Intelligence 23/APR/2020 Attacked and killed a Federal Police Forces member while riding his motorcycle in Found an ISIS hideout containing food, clothes, and motorcycle license plates in Umm Muqdadiya district, northeast of Diyala. Idham village, southwest of Mosul. ISIS 24/APR/2020 Federal Police Forces 24/APR/2020 Four mortar shells landed in the Al-Had Al-Ahdar area, injuring a civilian in Al-Ibarra Found a civilian corpse showing torture signs in the Kokjale area, east of Mosul. subdistrict, 14km northeast of Baqubah. ISIS 28/APR/2020 ISIS 25/APR/2020 Injured three civilians in an attack at Zalahfa village in Al-Shoora subdistrict, south of Bombarded the outskirts of Al-Zahra village using mortar shells in Al-Ibarra district. Mosul. ISIS 25/APR/2020 ISIS 29/APR/2020 Injured two Federal Police Forces members using a sniper rifle between Al-Kabaa and Abu Abducted a civilian in his workplace in the Al-Borsa area. -

3 4 3 Iraq Situation Report: January 12-15, 2015

Iraq Situation Report: January 12-15, 2015 1 On January 13, an anonymous security source in Anbar Operation Command stated 6 On January 14, Governor of Diyala Amir al-Majmai called for that ISF and tribal ghters, with U.S. air support, are in ongoing clashes with ISIS in the tribes in the areas of Sansal and Arab Jubur near Muqdadiyah to areas around Rutba district west of Qaim, and have killed 22 ISIS members. Forces volunteer to ght ISIS “to receive weapons.” Majmai explained that “continue advancing towards the entrances of Rutba from the northern and southern directions.” Also, “a senior source from Jazeera and Badia Operations Command such forces will “hold the ground” to prevent damage to these areas ( JBOC)” stated that the operation extends beyond Rutba to clearing Walid sub-district, following operations .He stated that he will have a leadership role in Walid crossing, the Trebil crossing with Jordan, and the Ar-Ar crossing with Saudi these operations. Meanwhile, the local government in Muqdadiyah Arabia. On January 14, joint forces supported by coalition air cover “cordoned” Rutba in stated that it received many requests from residents to clear areas north preparation to storm the district while communication and internet services in Rutba of Muqdadiyah that are being used to launch indirect re attacks on were suspended. Another report indicated that the joint forces “halted” their advance to fortify their positions in areas they cleared near Rutba. e source claimed that the forces the district. Also, ISIS has reportedly evacuated three of its “main cleared the areas of Sagara, Owinnat, and “80 km,” located east of Rutba, and Hussainiyat, headquarters” in the area of Sansal Basin in preparation for the northwest of Rutba, in addition to the areas of “120 km” and “60 km” on the highway and expected launch of military operations to clear ISIS from the area. -

Of Islamist Terrorist Attacks

ISLAMIST TERRORIST ATTACKS IN THE WORLD 1979-2019 NOVEMBER 2019 ISLAMIST TERRORIST ATTACKS IN THE WORLD 1979-2019 NOVEMBER 2019 ISLAMIST TERRORIST ATTACKS IN THE WORLD 1979-2019 Editor Dominique REYNIÉ, Executive Director of the Fondation pour l’innovation politique Editorial coordination Victor DELAGE, Madeleine HAMEL, Katherine HAMILTON, Mathilde TCHOUNIKINE Production Loraine AMIC, Victor DELAGE, Virginie DENISE, Anne FLAMBERT, Madeleine HAMEL, Katherine HAMILTON, Sasha MORINIÈRE, Dominique REYNIÉ, Mathilde TCHOUNIKINE Proofreading Francys GRAMET, Claude SADAJ Graphic design Julien RÉMY Printer GALAXY Printers Published November 2019 ISLAMIST TERRORIST ATTACKS IN THE WORLD Table of contents An evaluation of Islamist violence in the world (1979-2019), by Dominique Reynié .....................................................6 I. The beginnings of transnational Islamist terrorism (1979-2000) .............12 1. The Soviet-Afghan War, "matrix of contemporary Islamist terrorism” .................................. 12 2. The 1980s and the emergence of Islamist terrorism .............................................................. 13 3. The 1990s and the spread of Islamist terrorism in the Middle East and North Africa ........................................................................................... 16 4. The export of jihad ................................................................................................................. 17 II. The turning point of 9/11 (2001-2012) ......................................................21 -

Unhcr Position on Returns to Iraq

14 November 2016 UNHCR POSITION ON RETURNS TO IRAQ Introduction ......................................................................................................................................................... 1 Violations and Abuses of International Human Rights and International Humanitarian Law .......................... 3 Treatment of Civilians Fleeing ISIS-Held Areas to Other Areas of Iraq ............................................................ 8 Treatment of Civilians in Areas Formerly under Control of ISIS ..................................................................... 11 Treatment of Civilians from Previously or Currently ISIS-Held Areas in Areas under Control of the Central Government or the KRG.................................................................................................................................... 12 Civilian Casualties ............................................................................................................................................ 16 Internal and External Displacement ................................................................................................................. 17 IDP Returns and Returns from Abroad ............................................................................................................. 18 Humanitarian Situation ..................................................................................................................................... 20 UNHCR Position on Returns ...........................................................................................................................