Congestion Management Program

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Resident Newsletter | Winter 2015/2016 KEEPING YOU INFORMED

Pulse Resident Newsletter | Winter 2015/2016 KEEPING YOU INFORMED. In every quarterly issue of the Parkmerced Pulse, you’ll find important updates on the progress of implementing the Parkmerced Vision. In early 2016 you will begin seeing the property being prepared for construction and we’re committed to keeping you informed —and welcome your questions, comments, and concerns at any time. WHAT IS THE PARKMERCED VISION? RESIDENT PROTECTION The Parkmerced Vision is a long-term (approximately 20-30 years) project to Parkmerced is committed to protecting residents’ rent-controlled apartments for comprehensively replan and redesign Parkmerced. The Parkmerced Vision was as long as they choose to live at Parkmerced. approved by the City of San Francisco in 2011. The project will be constructed in phases, with construction of the Project’s Subphases 1A and 1B expected to The Parkmerced Vision involves removing and replacing all garden apartment begin in Spring and Summer 2016, respetively. Additional information about the homes within Parkmerced in phases over the next 20-30 years. Subphase 1A Parkmerced Vision is available at parkmercedvision.com. includes the construction of 56 replacement apartment homes for residents of to- be-replaced apartments on existing blocks 37W, 34, and 19 (see map on page 5). July 2011: Project Entitlement and Development Agreement Approved May 2015: Development Phase 1 Application Approved To protect our existing residents living at Parkmerced, prior to the replacement August 2015: Tentative Subdivision Maps for Subphases 1A and 1B Approved of any existing rent-controlled apartment, Parkmerced will provide the resident October through December 2015: Design Review Applications Approved who lives in a to-be-replaced building with an apartment within one of the newly constructed buildings in Parkmerced. -

This Print Covers Calendar Item No. : 10.4 San

THIS PRINT COVERS CALENDAR ITEM NO. : 10.4 SAN FRANCISCO MUNICIPAL TRANSPORTATION AGENCY DIVISION: Sustainable Streets BRIEF DESCRIPTION: Amending Transportation Code, Division II, Section 702 to modify speed limits at specific locations including deleting locations from the Transportation Code to reduce the speed limit to 25 miles per hour. SUMMARY: The City Traffic Engineer is authorized to conduct engineering and traffic surveys necessary to modify speed limits on City streets subject to approval by the SFMTA Board of Directors. The proposed action is the Approval Action as defined by S.F. Administrative Code Chapter 31. ENCLOSURES: 1. SFMTAB Resolution 2. Transportation Code legislation APPROVALS: DATE 5/24/2017 DIRECTOR _____________________________________ ____________ 5/24/2017 SECRETARY ______________________________________ ____________ ASSIGNED SFMTAB CALENDAR DATE: June 6, 2017 PAGE 2. PURPOSE Amending Transportation Code, Division II, Section 702 to modify speed limits at specific locations including deleting locations from the Transportation Code to reduce the speed limit to 25 miles per hour. STRATEGIC PLAN GOALS AND TRANSIT FIRST POLICY PRINCIPLES The proposed amendment to the Transportation Code to modify speed limits at specific locations supports the City’s Vision Zero Policy in addition to the SFMTA Strategic Plan Goal and Objective below: Goal 1: Create a safer transportation experience for everyone Objective 1.3: Improve the safety of the transportation system The proposed amendment to the Transportation Code also supports the SFMTA Transit-First Policy principle indicated below: Principle 1: To ensure quality of life and economic health in San Francisco, the primary objective of the transportation system must be the safe and efficient movement of people and goods. -

Mercy High School, San Francisco 3250 19Th Avenue | San Francisco, Ca

OWNER-USER / DEVELOPMENT OPPORTUNITY MERCY HIGH SCHOOL, SAN FRANCISCO 3250 19TH AVENUE | SAN FRANCISCO, CA Tom Christian Tim Garlick Executive Managing Director Director Direct +1 415 677 0424 Direct +1 415 568 3416 Mobile +1 415 509 8875 Mobile +1 415 596 8887 [email protected] [email protected] CA LIC #00890910 LIC #017159030 Sign Up Explore Prints Get Pro Photos, people, or groups Sign In Photo / All sizes License All rights reserved by PatricksMercy Download The owner has disabled downloading of their photos Sizes Square 75 (75 × 75) Small 240 (212 × 240) Medium 500 (442 × 500) Large 1024 (906 × 1024) X-Large 3K (2530 × 2860) Square 150 (150 × 150) Small 320 (283 × 320) Medium 640 (566 × 640) Large 1600 (1415 × 1600) Thumbnail (88 × 100) Small 400 (354 × 400) Medium 800 (708 × 800) Large 2048 (1812 × 2048) SISTERS OF MERCY / MISSION ALIGNMENT / CRITICAL CONCERNS • Emphasis on the Preferential Treatment of the Poor; • Faith-Based; • Considers the needs of the local community; • Recognizes the Educational Mission of Education for Young Women; • Does No Harm to Existing Mercy Institutions and Other Community Institutions that Share Mercy’s Educational Mission • Just and Humane Immigration Laws • Dismantling Institutional Racism • Special Attention to Women’s Health, Education, and Spirituality • Peace Through Prayer, Education, Personal and Communal Practices of Nonviolence • Right to Clean Water and Addressing Climate Change The Sellers of Mercy High School have dedicated their lives in service to the underprivileged and underrepresented. In considering the acquisition of the Mercy High School property we ask that you address in what ways your proposed project meets the mission and values of the Sisters of Mercy. -

This Print Covers Calendar Item No.: 10.2

THIS PRINT COVERS CALENDAR ITEM NO.: 10.2 SAN FRANCISCO MUNICIPAL TRANSPORTATION AGENCY DIVISION: Sustainable Streets – Transportation Engineering BRIEF DESCRIPTION: Approving various routine traffic and parking modifications. SUMMARY: Under Proposition A, the SFMTA Board of Directors has authority to adopt parking and traffic regulations changes. Taxis are not exempt from any of these regulations. ENCLOSURE: 1. SFMTAB Resolution APPROVALS: DATE DIRECTOR OF DIVISION PREPARING ITEM ____________ DIRECTOR ____________ SECRETARY ____________ ADOPTED RESOLUTION BE RETURNED TO Tom Folks . ASSIGNED SFMTAB CALENDAR DATE: PAGE 2. PURPOSE To approve various routine traffic and parking modifications. GOAL This action is consistent with the SFMTA 2008-2012 Strategic Plan. Goal 1: Customer Focus – To provide safe, accessible, reliable, clean and environmentally sustainable service and encourage the use of auto-alternative modes through the Transit First Policy. Objective 1.1: Improve safety and security across all modes of transportation. Goal 2: System Performance – To get customers where they want to go, when they want to be there. Objective 2.4: Reduce congestion through major corridors. Objective 2.5: Manage parking supply to align with SFMTA and community goals. ITEMS A. ESTABLISH – 15 MILES PER HOUR SPEED LIMIT WHEN CHILDREN PRESENT – Eddy Street between Van Ness Avenue and Laguna Street Ellis Street between Franklin and Gough Street McAllister Street between Octavia and Franklin streets 12th Avenue between Kirkham and Moraga streets 14th Avenue -

Short Range Transit Plan

SHORT RANGE TRANSIT PLAN SFMTA.COM Fiscal Year 2017 - Fiscal Year 2030 2 Federal transportation statutes require that the Metropolitan Transportation Commission (MTC), in partnership with state and local agencies, develop and periodically update a long-range Regional Transportation Plan (RTP), and a Transportation Improvement Program (TIP) which implements the RTP by programming federal funds to transportation projects contained in the RTP. In order to effectively execute these planning and programming responsibilities, MTC requires that each transit operator in its region which receives federal funding through the TIP, prepare, adopt and submit to MTC a Short Range Transit Plan (SRTP). The preparation of this report has been funded in part by a grant from the U.S. Department of Transportation (DOT) through section 5303 of the Federal Transit Act. The contents of this SRTP reflect the views of the San Francisco Municipal Transportation Agency, and not necessarily those of the Federal Transit Administration (FTA) or MTC. San Francisco Municipal Transportation Agency is solely responsible for the accuracy of the information presented in this SRTP. SFMTA FY 2017 - FY 2030 SRTP Anticipated approval by the SFMTA Board of Directors: Middle of 2017 TABLE OF CONTENTS 1. OVERVIEW OF THE SFMTA TRANSIT SYSTEM 7 Brief History 7 Governance 8 Transit Services 12 TABLE OF CONTENTS OF TABLE Overview of the Revenue Fleet 17 Existing Facilities 18 2. SFMTA GOALS, OBJECTIVES & STANDARDS 27 The SFMTA Strategic Plan 27 FY 2013 - FY 2018 Strategic Plan Elements 29 SFMTA Performance Measures 30 3. SERVICE & SYSTEM EVALUATION 35 Current Systemwide Performance 35 Muni Transit Service Structure 40 Muni Service Equity Policy 41 Equipment & Facilities 42 MTC Community-Based Transportation Planning Program 42 Paratransit Services 43 Title VI Analysis & Report 44 3 FTA Triennial Review 44 4. -

History Evening

MAY2017 JOURNAL OF THE HISTORY GUILD OF DALY CITY ..COLMA I GREETINGS FROM PRESIDENT MARK HISTORY EVENING We have a great new speaker for our May general membership Wednesday, May 17th meeting. Bob Calhoun is a local historian and author who will share at7 pm tales of the Penny Bjorkland case and his family's connection to it. Who was Penny Bjorkland? Attend and learn all about the three M's: murder, mayhem, and mystery. If time permits he'll also discuss another femme fatale with connections to Daly City, a certain gal you might have heard of going by the name Patty Hearst. This is sure to be another fantastic presentation you won't want to miss. At the May meeting we will vote on a board of directors as we do every two years. I can report that we received no inquiries from individuals expressing an interest in running for the board. Therefore, the current officers and directors have agreed to run for re-election. The Guild Local historian and author recommended slate appears on page :3. BOSCALHOUN presents Finally, for those who like to promote history, please consider a new first class commemorative postage stamp currently for sale at many post offices. The following is DANGEROUS taken directly from the USPS web site: I¥OMEN! "The U.S. Postal Service celebrates posters of the Work Projects Administration, striking and utilitarian artwork created during the Depression by the Poster Division of 101 Lake Merced Blvd, Daly City the WPA Federal Art Project. This booklet features 20 Doelger Center Cafe stamps of 10 different designs originally created to support the civic-minded ideals of Franklin D. -

DRIVING to CAMPUS: from Highway 101 North & South: Take The

DRIVING TO CAMPUS: From Highway 101 North & South: Take the Embarcadero Road exit west toward Stanford. At El Camino Real, Embarcadero turns into Galvez Street as it enters the university. Turn right onto Campus Drive, and follow it around to Panama Street. Turn left onto Panama Street. There will be an open parking lot on your right, and a parking structure on your left. You may park in either location. The Durand Building is to the left at the end of Panama Street as it curves around and becomes Samuel Morris Way. From Highway 280 North & South: Exit 280 at Sand Hill Road, heading east. Make a right turn on Santa Cruz Avenue, then a left turn onto Junipero Serra Boulevard. Turn right at the third stoplight, Campus Drive West. Continue around Campus Drive West and turn right when you reach Panama Street. There will be an open parking lot on your right, and a parking structure on your left. You may park in either location. The Durand Building is to the left at the end of Panama Street as it curves around and becomes Samuel Morris Way. From El Camino Real: Exit El Camino Real at University Avenue. Turn toward the hills (away from the center of Palo Alto). As you enter Stanford, University Avenue becomes Palm Drive. Go through one traffic light, and turn right onto Campus Drive. Turn left onto Panama Street. There will be an open parking lot on your right, and a parking structure on your left. You may park in either location. The Durand Building is to the left at the end of Panama Street as it curves around and becomes Samuel Morris Way. -

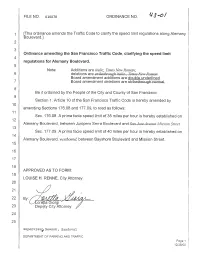

Ordinance Amending the San Francisco Traffic Code, Clarifying the Speed Limit 4 Regulations for Alemany Boulevard

FILE NO. 010078· ORDINANCE NO. 1./3-01 1 [This ordinance amends the Traffic Code to clarify the speed limit regulations along Alemany Boulevard.] 2 3 Ordinance amending the San Francisco Traffic Code, clarifying the speed limit 4 regulations for Alemany Boulevard. 5 Note: Additions are italic; Times New Roman; 6 de Ieti Ions are strlJW\l1rougJ1'1 :p u[fadO.,zmes : 7' 'J!l' lyell'lIT loman~ Board amendment additions are double underlined. 7 Board amendment deletions are strikethrough normal. 8 Be it ordained by the People of the City and County of San Francisco: 9 Section 1. Article 10 of the San Francisco Traffic Code is hereby amended by 10 amending Sections 176.0B and 177.09, to read as follows: 11 Sec. 176.08 A prima facie speed limit of 35 miles per hour is hereby established on 12 Alemany Boulevard, between Junipero Serra Boulevard and San Jose Avenue .Mission Street. Sec. 177.09 A prima facie speed limit of 40 miles per hour is hereby established on Alemany Boulevard, westbound, between Bayshore Boulevard and Mission Street. 15 16 17 18 APPROVED AS TO FORM: 19 LOUISE H. RENNE, City Attorney 20 21 22 By: r.or~tta Giorgi 23 Dep~lty City Attorney v 24 25 Superviso~ Newsom, Sandoval DEPARTMENT OF PARKING AND TRAFFIC Page 1 II 12/29/00 City Hall City and County of San Francisco 1 Dr. Carlton B. Goodlett Place San Francisco, CA 94102-4689 Tails Ordinance File Number: 010078 Date Passed: Ordinanceamendlnq the San Francisco Traffic Code, clarifying the speed limit regulations for Alemany Boulevard. -

Interim Controls on Major Rights of Way Along & Near

New Planning Code Change Summary: Interim Controls on Major Rights of Way Along & Near the Southern 19th Avenue Corridor Code Change: 18 month interim control requiring CU use authorization for new residential developments over 20 units and for new commercial or retail developments over 50,000 square feet (see attached map) Case Number: Board File No. 08‐1004 (0457‐08 adopted Resolution) Initiated By: Supervisor Elsbernd, September 9, 2008 Effective Date: November 7, 2008 Expiration Date: May 1, 2010 The Way It Was: No interim controls. The Way It Is Now: The proposed ordinance would require Conditional Use authorization for new residential developments over 20 units and for new commercial or retail developments over 50,000 square feet on both sides of the following rights of way along and near the Southern 19th Avenue Corridor: commencing at Lake Merced Boulevard where it begins at the County line, north along Lake Merced Boulevard to Sloat Boulevard, east along Sloat Boulevard to 19th Avenue, north along 19th Avenue to Taraval Street, east on Taraval Street to Claremont, south on Claremont to Portola, southwest on Portola to Junipero Serra Boulevard, and south on Junipero Serra Boulevard to the County line. Please note that in addition to the standard CU requirements the interim controls further require that projects submit parking and traffic studies for the area surrounding the proposed project, which shall be at least, north to Taraval Street and west to the Great Highway and Skyline Boulevard. The Planning Commission (and the Board of Supervisors on Appeal) shall make findings that proposed project will not decrease pedestrian safety and worsen traffic conditions such as to cause a significant impact at major intersections in the surrounding area in the absence of mitigation measures to lessen those traffic impacts or any other negative physical environmental impact or make specific findings that such mitigation is infeasible. -

September 2017 Millbrae Life & Times

September 2017 Millbrae Life & Times MILLBRAE HISTORICAL SOCIETY NEWSLETTER Historical Spotlight: Highway District 10 INSIDE THIS I S S U E : By Tom Dawdy If you ask the average person on the street in Millbrae, “What was Highway District 101010 ?”, I would bet that most people have never heard of it. This proposed infrastructure Historical Spotlight 1 project would have split Millbrae in half, and Millbrae would be much different than it is today, but fortunately it never happened. Highway District 10 owned the rights to ex- President’s Report 1 tend Junipero Serra Boulevard through Millbrae. In 1951, the project was moving south, and the extension was already under construction between Sneath Lane and Vice-President’s Message 3 Crystal Springs Road in San Bruno. The new plan was presented to the public with the proposed route running through Millbrae ending up at Trousdale Drive. Millbrae Now and Then 3 Curator’s Report 5 Millbrae’s popular Spur Trail was once the planned route Train Museum News 5 for the Junipero Serra Highway Calendar of Events 6 By 1954, everyone in Millbrae was up in arms about this project, and the Millbrae City Council agreed to take action. One of the actions was to order a major traffic study. (continued on Page 4) President’s Report John Muniz I am extremely happy to report to come in and restore the side yard. our members that great progress What are we going to do to fill such has been made on the Carriage a large interior space? Originally, we House. -

3.13 Transportation, Traffic, Circulation, and Parking San Francisco VA Medical Center

3.13 Transportation, Traffic, Circulation, and Parking San Francisco VA Medical Center 3.13 TRANSPORTATION, TRAFFIC, CIRCULATION, AND PARKING This section summarizes the traffic, transportation, circulation, and parking impacts, including transit, pedestrian, bicycle, and loading impacts, that are projected to result from implementation of the EIS Alternatives. A detailed transportation impact analysis was prepared and is included in Appendix E. 3.13.1 Affected Environment Regional and Local Access Existing Fort Miley Campus The existing SFVAMC Fort Miley Campus is a 29-acre site located in northwestern San Francisco. The site is positioned along the north side of Clement Street, with access points at 42nd Avenue and 43rd Avenue (Figure 3.13-1). Regional and local access points to and from the existing Campus are summarized below. Regional Access State Route (SR) 1, U.S. Highway 101 (U.S. 101), Interstate 80 (I-80), and Interstate 280 (I-280) provide regional access to and from the existing SFVAMC Fort Miley Campus. East Bay Regional vehicular access to and from the East Bay is provided primarily by I-80 and the Bay Bridge, with on- and off-ramps at First Street/Fremont Street/Essex Street/Bryant Street in Rincon Hill, Fourth Street/Fifth Street in the central South of Market Area, and Seventh Street/Eighth Street in the western South of Market Area. Alternative access to I-80 is provided via U.S. 101 and the U.S. 101/I-80 interchange, which can be accessed via the Central Freeway ramps at Mission Street/South Van Ness Avenue or the U.S. -

Contents Attachments: 1

SOC ATTACHMENT STANFORD UNIVERSITY UNIVERSITY ARCHITECT / CAMPUS PLANNING AND DESIGN Contents Attachments: 1. CASBS Evaluation – 2018 GUP application 2. CASBS Evaluation – January 2021 3. TPS Preservation Brief #14 – New Exterior Additions to Historic Buildings: Preservation Concerns. Additional Information: 1. Stanford University - Design Philosophy for Architectural Compatibility – April 2020 2. Architectural Team Qualifications – Olson Kundig Architects 340 BONAIR SIDING • PALO ALTO, CA 94305-8442 0 01/2021 State of California The Resources Agency Primary # SOC ATTACHMENT DEPARTMENT OF PARKS AND RECREATION HRI # PRIMARY RECORD Trinomial NRHP Status Code 3CS Other Listings Review Code Reviewer Date Page 1 of 8 *Resource Name or #: (Assigned by recorder) Center for Advanced Study in the Behavioral Sciences P1. Other Identifier: Stanford University Building 12-200 (main building), 12-210 (studios 1-6), 12-220 (studios 7-12), 12-230 (studios 13-16), 12-240 (studios 17-20), 12-250 (studios 21-25), 12-270 (studios 30-37), 12-280 (studios 38-54) *P2. Location: Not for Publication Unrestricted *a. County Santa Clara and (P2c, P2e, and P2b or P2d. Attach a Location Map as necessary.) *b. USGS 7.5’ Quad Palo Alto Date T ; R ; of of Sec ; B.M. c. Address 75 Alta Road City Stanford Zip 94305 d. UTM: (Give more than one for large and/or linear resources) Zone 1, 572560 mE/ 4141728 mN e. Other Locational Data: (e.g., parcel #, directions to resource, elevation, etc., as appropriate) *P3a. Description: (Describe resource and its major elements. Include design, materials, condition, alterations, size, setting, and boundaries) The Center for Advanced Study in the Behavioral Sciences (also known as CASBS) is a complex of thirteen buildings built in different phases: four were part of the Alta Vista farm, seven were built in 1954, one in 1955, and between 1969-79.