Economic Analysis of Critical Habitat Designation for the Southwest Alaska Distinct Population Segment of the Northern Sea Otter

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Notice of Adjustments to Service Obligations

Served: May 12, 2020 UNITED STATES OF AMERICA DEPARTMENT OF TRANSPORTATION OFFICE OF THE SECRETARY WASHINGTON, D.C. CONTINUATION OF CERTAIN AIR SERVICE PURSUANT TO PUBLIC LAW NO. 116-136 §§ 4005 AND 4114(b) Docket DOT-OST-2020-0037 NOTICE OF ADJUSTMENTS TO SERVICE OBLIGATIONS Summary By this notice, the U.S. Department of Transportation (the Department) announces an opportunity for incremental adjustments to service obligations under Order 2020-4-2, issued April 7, 2020, in light of ongoing challenges faced by U.S. airlines due to the Coronavirus (COVID-19) public health emergency. With this notice as the initial step, the Department will use a systematic process to allow covered carriers1 to reduce the number of points they must serve as a proportion of their total service obligation, subject to certain restrictions explained below.2 Covered carriers must submit prioritized lists of points to which they wish to suspend service no later than 5:00 PM (EDT), May 18, 2020. DOT will adjudicate these requests simultaneously and publish its tentative decisions for public comment before finalizing the point exemptions. As explained further below, every community that was served by a covered carrier prior to March 1, 2020, will continue to receive service from at least one covered carrier. The exemption process in Order 2020-4-2 will continue to be available to air carriers to address other facts and circumstances. Background On March 27, 2020, the President signed the Coronavirus Aid, Recovery, and Economic Security Act (the CARES Act) into law. Sections 4005 and 4114(b) of the CARES Act authorize the Secretary to require, “to the extent reasonable and practicable,” an air carrier receiving financial assistance under the Act to maintain scheduled air transportation service as the Secretary deems necessary to ensure services to any point served by that air carrier before March 1, 2020. -

Report to Congress on the Airport Improvement Program for FY 2018

Office of the Administrator 800 Independence Ave., SW. Washington, DC 20591 August 26, 2020 The Honorable Michael R. Pence President United States Senate Washington, DC 20510 Dear Mr. President: Enclosed is the 32nd Report of Accomplishments under the Airport Improvement Program (AIP) for Fiscal Year 2018. As required by 49 United States Code, section 47131, this report provides information about the AIP and the Airport Land Use Compliance Program. The purpose of the AIP is to assist in airport development to meet the Nation’s current and future aviation needs, while continuing to optimize safety, capacity, and efficiency. This report summarizes Federal investments in airport infrastructure during the reporting period. A similar letter has been sent to the Speaker of the House of Representatives. Sincerely, Steve Dickson Administrator Enclosure Office of the Administrator 800 Independence Ave., SW. Washington, DC 20591 August 26, 2020 The Honorable Nancy Pelosi Speaker United States House of Representatives Washington, DC 20515 Dear Madam Speaker: Enclosed is the 32nd Report of Accomplishments under the Airport Improvement Program (AIP) for Fiscal Year 2018. As required by 49 United States Code, section 47131, this report provides information about the AIP and the Airport Land Use Compliance Program. The purpose of the AIP is to assist in airport development to meet the Nation’s current and future aviation needs, while continuing to optimize safety, capacity, and efficiency. This report summarizes Federal investments in airport infrastructure -

State of Alaska the Legislature

131ectioll I)istrict State of Alaska The Legislature -- JUNEAU ALA8KA THE BUDGET BY ELECTION DISTRICT The enclosed report lists elements of the budget by election district for the House of Representatives. The report presents the following three types of information for each election district: 1. Positions approved by the Legislature; 2. Capital Budget Projects; 3. Bond and Special Appropriations projects. The report lists whole budget line items only, (amounts added to statewide/areawide budget items for a specific location are not listed) and is intended to provide some indication of th~ level of increased or new state programs and services within any given district. When used in conjunction with the State Salaries by Location Report it should give a relatively good indication of the level of state expenditures within a given election district. TABLE OF CONTENTS ELECTION DISTRICT DISTRICT NAME PAGE NO. ~ PROJECTS POSITIONS* 01 Ketchikan 3 109-' 02 Wrange11~Petersburg 7 110 03 Sitka 11 III 04 Juneau 15 112 05 Cordova-Va1dez-Seward 23 119-- -06 Palmer-Wasi11a-Matanuska 29 120 07 - 12 'Anchorage 35 121 13 Kenai-Soldotna-Homer 49 129 '-' 14 Kodiak 53 130 15 Aleutian Islands-Kodiak 57 131 16 Dillingham-Bristol Bay 63 ' 132 17 Bethel-Lower Kuskokwim 69 133 18 Ga1ena-McGrath-Hooper Bay 75 134· 19 Nenana-Fort.Yukon-Tok 81 135 20 Fairbanks 87 136 21 Barrow-Kotzebue 97 140 ----- , 22 Nome-Seward Peninsula 103 141 * yellow section SPECIAL APPROPRIATIONS, BONDS AND CAPITAL PROJECTS BY ELECTION DISTRICT ($ millions - all funds) 1977 Session 1978 -

Governor's Capital Budget - Appropriations and Allocations (By Department) Governor's 2002 Capital Budget

Governor's Capital Budget - Appropriations and Allocations (by department) Governor's 2002 Capital Budget General G/F Match UA/ICR (1039) AHFC Div Federal Other Total Funds Agency Project Title Funds (1003) (1139) Funds Funds Department of Administration Pioneers' Homes Emergency Repairs and Maintenance AP 100,000 0 0 250,000 0 0 350,000 Pioneers' Homes Alzheimer's Disease and Related Disabilities AP 0 0 0 0 0 250,000 250,000 Modifications Adult Day Facility Prototype Design for Dementia Clients AP 0 0 0 0 0 30,000 30,000 Payroll and Accounting System Replacement Analysis AP 400,000 0 0 0 0 0 400,000 State-Owned Buildings Valuation Project AP 60,000 0 0 0 0 0 60,000 ARCS Video Automation and Control Project AP 77,500 0 0 0 0 0 77,500 License Plates and Drivers License Manuals AP 345,000 0 0 0 0 0 345,000 Emergency Communications: Land Mobile Radio Migration AP 1,354,400 0 0 0 14,893,700 0 16,248,100 Electronic Signatures Project AP 100,000 0 0 0 0 0 100,000 Mainframe Improvements, Equipment Replacement, Virus Scanning, AP 0 0 0 0 0 2,181,000 2,181,000 and Metadirectory Development Upgrade Internet and Intranet, and Implement New Network AP 0 0 0 0 0 539,900 539,900 Technology Department of Administration Subtotal 2,436,900 0 0 250,000 14,893,700 3,000,900 20,581,500 Department of Commerce, Community, and Economic Development Language Section: Power Cost Equalization AP 4,680,000 0 0 0 0 3,120,000 7,800,000 Securities Database AP 0 0 0 0 0 300,000 300,000 Operation Renew Hope AP 0 500,000 0 0 30,000,000 0 30,500,000 Community Block Grants -

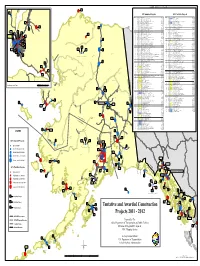

2011 Awarded Projects 2012 Tentative Projects

Barrow 158 (!H! 36 (! 2011 Awarded Projects 2012 Tentative Projects Goose Bay H! Map_Number Region Mode Project_Name Programmed Map_Number Region Mode Project_Name Programmed Wainwright 1NorthernHighwayVALDEZ AIRPORT ACCESS ROAD RESURFACING $854,910.00 92 Southeast Marine HNS TERMINAL IMPROVEMENTS $10,000,000.00 H! 2NorthernHighwayRICHARDSON HWY FLOODING PERMANENT REPAIRS (OCT '06) $10,640,978.00 93 Southeast Highway SGY DYEA RD IMPROVEMENTS $3,200,000.00 3 Northern Highway MCCARTHY RD & EDGERTON HWY FLOOD PERMANENT REPAIRS (OCT '06) $1,286,416.00 94 Southeast Highway JNU EGAN DRIVE YANDUKIN INTERSECTION SAFETY ENHANCEMENTS $697,284.00 Atqasuk (! H! 4NorthernHighwayTAYLOR HWY MP 70 LOST CHICKEN SLIDE $2,055,729.00 95 Southeast Marine WRG FERRY TERMINAL IMPROVEMENTS $600,000.00 123 Kaktovik H! 5NorthernHighwayRICHARDSON HWY FLOODING PERM REPAIRS‐12.8 MILE DIKE $1,367,581.00 96 Southeast Marine PSG FERRY TERMINAL IMPROVEMENTS $2,000,000.00 Prudhoe Bay (! H!Deadhorse 6NorthernHighwayDALTON HWY MP 254‐414 DELINEATORS $2,837,029.00 97 Southeast Highway SITKA SAWMILL CREEK ROAD UPGRADE (GO BOND) $13,000,000.00 Nuiqsut H! H! (! 7SoutheastHighwaySGY DYEA ROAD BRIDGE #309 REHABILITATION‐TAIYA RIVER BRIDGE $1,429,672.00 98 Northern Highway NOME SNAKE RIVER BRIDGE REPLACEMENT (GO BOND) $10,000,000.00 113 71 8NorthernHighwayMARSHALL AIRPORT ACCESS ROAD BRIDGE REPLACEMENT $5,451,711.00 99 Northern Highway VALDEZ TIDAL FLATS CULVERT REPLACEMENT AK122 $1,506,000.00 (! 9NorthernHighwayVAN HORN ROAD WEST (CARTWRIGHT ROAD) IMPROVEMENTS $1,703,946.00 100 -

06-'12, Rural Airports AIP Spending Plan October 20, 2010 DOT/PF, Statewide Aviation

Draft FFY '06-'12, Rural Airports AIP Spending Plan October 20, 2010 DOT/PF, Statewide Aviation APEB LOCID Project Score Ph FFY'06 FFY'07 FFY'08 FFY'09 FFY'10 FFY'11 FFY'12 After FFY'12 Rural Primary Airports Primary Airfield Projects ANI Aniak Airport Improvements 130 2,3,4 $ 4,700,000 BRW Barrow Apron Expansion 88 2,4 $ 7,000,000 BRW Barrow RWY-Apron Paving/ SA Expan-Stg 3 124 2,4$ 3,000,000 BRW Barrow RWY-Apron Paving/ SA Expan-Stg 4 124 2,4 $ 7,200,000 Bethel Parallel RWY and Other Improv--Stg 2 BET (GA Apron Expansion) 130 2,4$ 5,701,583 Bethel Parallel RWY and Other Improv--Stg 3 (Parallel Runway Gravel Surface and BET Lighting) 160 2,4$ 2,733,217 Bethel Parallel RWY and Other Improv--Stg 4 (Parallel Runway Gravel Surface and BET Lighting) 160 2,4$ 5,877,983 Bethel Parallel RWY and Other Improv--Stg 5 BET (Parallel Runway Paving) 160 2,4$ 3,277,634 Bethel Parallel RWY and Other Improv--Stg 6 BET (ROW) 130 2,4 $ 1,650,000 BET Bethel West Heavy Apron Expansion 101 2,4 $ 4,000,000 Bethel Airport RWY / TWY / Commerical BET Apron Pavement Rehabilitation (C) N/A 2,4 $ 13,000,000 Bethel Airport RWY / TWY / Commerical BET Apron Pavement Rehabilitation N/A 2,4 $ 13,000,000 BET Bethel South GA Apron Reconstruction (C) N/A 2,4 $ 4,700,000 BET Bethel South GAApron Reconstruction N/A 2,4 $ 4,700,000 CDV Cordova Apt Apron, TWY & GA Imp Stg 1 113 2,4$ 4,499,980 CDV Cordova Apt Apron, TWY & GA Imp Stg 2 113 2,4 $ 8,500,000 CDV Cordova Apt Apron, TWY & GA Imp Stg 2 (C) 113 2,4 $ 8,500,000 CDV Cordova Apt Apron, TWY & GA Imp Stg 3 113 2,4 $ 6,700,000 CDV Cordova Apt RSA Expan - Stg 2 N/A 2,4$ 4,346,424 CDV Cordova Apt RSA Improvements (Paving) 65 2,4$ 650,000 Note: Spending Plan contains entitlement and discretionary funded projects. -

United States of America Department of Transportation Office of the Secretary Washington, D.C. Continuation of Certain Air

Served: May 12, 2020 UNITED STATES OF AMERICA DEPARTMENT OF TRANSPORTATION OFFICE OF THE SECRETARY WASHINGTON, D.C. CONTINUATION OF CERTAIN AIR SERVICE PURSUANT TO PUBLIC LAW NO. 116-136 §§ 4005 AND 4114(b) Docket DOT-OST-2020-0037 NOTICE OF ADJUSTMENTS TO SERVICE OBLIGATIONS Summary By this notice, the U.S. Department of Transportation (the Department) announces an opportunity for incremental adjustments to service obligations under Order 2020-4-2, issued April 7, 2020, in light of ongoing challenges faced by U.S. airlines due to the Coronavirus (COVID-19) public health emergency. With this notice as the initial step, the Department will use a systematic process to allow covered carriers1 to reduce the number of points they must serve as a proportion of their total service obligation, subject to certain restrictions explained below.2 Covered carriers must submit prioritized lists of points to which they wish to suspend service no later than 5:00 PM (EDT), May 18, 2020. DOT will adjudicate these requests simultaneously and publish its tentative decisions for public comment before finalizing the point exemptions. As explained further below, every community that was served by a covered carrier prior to March 1, 2020, will continue to receive service from at least one covered carrier. The exemption process in Order 2020-4-2 will continue to be available to air carriers to address other facts and circumstances. Background On March 27, 2020, the President signed the Coronavirus Aid, Recovery, and Economic Security Act (the CARES Act) into law. Sections 4005 and 4114(b) of the CARES Act authorize the Secretary to require, “to the extent reasonable and practicable,” an air carrier receiving financial assistance under the Act to maintain scheduled air transportation service as the Secretary deems necessary to ensure services to any point served by that air carrier before March 1, 2020. -

Governor's Capital Budget - Appropriations and Allocations (By Department) FY2003 Governor's Amended

Governor's Capital Budget - Appropriations and Allocations (by department) FY2003 Governor's Amended General G/F Match UA/ICR (1039) AHFC Div Federal Other Total Funds Agency Project Title Funds (1003) (1139) Funds Funds Department of Administration Payroll and Accounting System Replacement Analysis AP 600,000 0 0 0 0 0 600,000 AMD: Driver License Testing Machines AP 197,400 0 0 0 417,300 0 614,700 Labor Contract Negotiations AP 461,000 0 0 0 0 0 461,000 Pioneers' Homes Emergency Repair and Maintenance AP 800,000 0 0 0 0 0 800,000 License Plates, Tabs and Manuals AP 281,000 0 0 0 0 0 281,000 Emergency Maintenance Projects for Facilities Outside the Public AP 800,000 0 0 0 0 0 800,000 Building Fund Adult Day Facility Modifications AP 250,000 0 0 0 0 0 250,000 Fixed Asset Accounting System AP 85,000 0 0 0 0 170,000 255,000 Public Defender Integrated Computer System AP 175,000 0 0 0 0 0 175,000 Public Facilities Maintenance and Repairs AP 0 0 0 0 0 2,500,000 2,500,000 Senior Services Data Integration Project - Phase 2 AP 0 0 0 0 0 238,000 238,000 Alaska Gas Development Study AP 0 0 0 0 0 500,000 500,000 Electronic Permitting Initiative AP 0 0 0 0 0 500,000 500,000 Combined Retirement Benefits Calculation System AP 0 0 0 0 0 436,000 436,000 Information Technology Group Equipment Replacement AP 0 0 0 0 0 5,904,400 5,904,400 Department of Administration Subtotal 3,649,400 0 0 0 417,300 10,248,400 14,315,100 Department of Commerce, Community, and Economic Development Electronic Document Imaging, Storage and Retrieval System AP 0 0 0 0 0 1,125,000 -

ANTHC Public Record

Site Name Site Status Site Type ACRES Property ID Street Address/P.O. Box (Address) City (Address) State (Address) Zip Code (Address) County (Address) Latitude Longitude Horizontal Reference Datum Property video/photos available Property documents available Property photographs available Ownership Entity Other Comments 315 9 296 8 6 7 5 299 23 22 243 24 25 300 206 254 SITKINAK AFS (http://dec.alaska.gov/Applications/SPAR/Public MVC/CSP/SiteReport/184) Sitkinak AFS Open Mixed Use 184 Sitkinak Island Sitkinak Island, Akhiok AK 99615 USA 56.54804 -154.15919 No No No Government(Tribal,State,Local) USCG Loran C Station - Sitkinak (http://dec.alaska.gov/Applications/SPAR/Public MVC/CSP/SiteReport/3055) USCG Loran C Station - Sitkinak Open Petroleum Site 3055 Sitkinak Island, West of Mark Lake Akhiok AK 99615 USA 56.540278 -154.132778 No No No Alitak Cannery (http://dec.alaska.gov/Applications/SPAR/Public MVC/CSP/SiteReport/26374) Lazy Bay; ~4 Miles SW of Akhiok; Kodiak Island Alitak Cannery Open Dump / Landfill 26374 NWR akhiok AK 99615 USA 56.900672 -154.251228 No No No FAA Chirikof Island Radio Range Facility http://dec.alaska.gov/Applications/SPAR/PublicM VC/CSP/SiteReport/26412 Northern Tip of Chirikof Island; ~90 Miles SSW FAA Chirikof Island Radio Range Facility Open Other (describe in Comments tab) 26412 of Akhiok Akhiok AK 99615 USA 55.90703 -155.589837 World Geodetic System of 1984 No No No USCG Cape Sarichef LORAN and Light http://dec.alaska.gov/Applications/SPAR/PublicM VC/CSP/SiteReport/28 USCG Cape Sarichef LORAN and Light Open Dump / Landfill 28 Cape Sarichef, NW end of, Unimak Island Akutan AK 99553 USA 54.598333 -164.925833 World Geodetic System of 1984 No No No USCG Scotch Cap Facility (http://dec.alaska.gov/Applications/SPAR/Public MVC/CSP/SiteReport/29) The site was used to operate a lighthouse and associated navigational aide support between 1903 and the 1970s. -

Governor's Capital Budget - Appropriations and Allocations (By Department) FY02 Final Capital Budget

Governor's Capital Budget - Appropriations and Allocations (by department) FY02 Final Capital Budget General G/F Match UA/ICR (1039) AHFC Div Federal Other Total Funds Agency Project Title Funds (1003) (1139) Funds Funds Department of Administration Pioneers' Homes Emergency Repairs and Maintenance AP 100,000 0 0 250,000 0 0 350,000 Pioneers' Homes Alzheimer's Disease and Related Disabilities AP 0 0 0 0 0 250,000 250,000 Modifications Adult Day Facility Prototype Design for Dementia Clients AP 0 0 0 0 0 30,000 30,000 ARCS Video Automation and Control Project AP 23,860 0 0 53,640 0 0 77,500 License Plates and Drivers License Manuals AP 275,000 0 0 0 0 0 275,000 Emergency Communications: Land Mobile Radio Migration AP 120,000 0 0 0 14,893,700 539,900 15,553,600 Mainframe Improvements, Equipment Replacement, Virus Scanning, AP 0 0 0 0 0 2,181,000 2,181,000 and Metadirectory Development Upgrade Internet and Intranet, and Implement New Network AP 0 0 0 0 0 539,900 539,900 Technology Alaska Public Telecommunications, Inc. - Digital Television Conversion AP 300,000 0 0 0 0 0 300,000 KTOO/Telecommunications, Inc. - Digital Television Conversion AP 350,000 0 0 0 0 0 350,000 KUAC/Telecommunications, Inc. - Digital Television Conversion AP 350,000 0 0 0 0 0 350,000 Department of Administration Subtotal 1,518,860 0 0 303,640 14,893,700 3,540,800 20,257,000 Department of Commerce, Community, and Economic Development City of Adak-Adak Port, Road and Other Infrastructure Improvements AP 0 0 0 300,000 0 0 300,000 Kodiak College Parking Lot Expansion -

Governor's Capital Budget - Appropriations and Allocations (By Department) FY2003 Final Capital

Governor's Capital Budget - Appropriations and Allocations (by department) FY2003 Final Capital General G/F Match UA/ICR (1039) AHFC Div Federal Other Total Funds Agency Project Title Funds (1003) (1139) Funds Funds Department of Administration Payroll and Accounting System Replacement Analysis AP 600,000 0 0 0 0 0 600,000 Driver License Testing Machines AP 197,400 0 0 0 417,300 0 614,700 Pioneers' Homes Emergency Repair and Maintenance AP 600,000 0 0 0 0 0 600,000 License Plates, Tabs and Manuals AP 281,000 0 0 0 0 0 281,000 Emergency Maintenance Projects for Facilities Outside the Public AP 300,000 0 0 0 0 0 300,000 Building Fund Adult Day Facility Modifications AP 250,000 0 0 0 0 0 250,000 Fixed Asset Accounting System AP 0 0 0 0 0 170,000 170,000 Public Defender Integrated Computer System AP 175,000 0 0 0 0 0 175,000 Public Facilities Maintenance and Repairs AP 0 0 0 0 0 2,500,000 2,500,000 Senior Services Data Integration Project - Phase 2 AP 0 0 0 0 0 238,000 238,000 Alaska Gas Development Study AP 0 0 0 0 0 500,000 500,000 Electronic Permitting Initiative AP 0 0 0 0 0 500,000 500,000 Combined Retirement Benefits Calculation System AP 0 0 0 0 0 436,000 436,000 Information Technology Group Equipment Replacement AP 0 0 0 0 0 3,140,000 3,140,000 Department of Administration Subtotal 2,403,400 0 0 0 417,300 7,484,000 10,304,700 Department of Commerce, Community, and Economic Development Homer Electric Association- Replacement power supply for Seldovia AP 0 0 0 0 0 2,000,000 2,000,000 Golden Valley Electric Association- Parks Highway -

Governor's Capital Budget - Appropriations and Allocations (By Department) FY2002 Governor's Amended

Governor's Capital Budget - Appropriations and Allocations (by department) FY2002 Governor's Amended General 1003 G/F Match 1039 UA/ICR 1139 AHFC Div Federal Other Total Funds Agency Project Title Funds Funds Funds Department of Administration Pioneers' Homes Emergency Repairs and Maintenance AP 100,000 0 0 250,000 0 0 350,000 Pioneers' Homes Alzheimer's Disease and Related Disabilities AP 0 0 0 0 0 250,000 250,000 Modifications Adult Day Facility Prototype Design for Dementia Clients AP 0 0 0 0 0 30,000 30,000 Payroll and Accounting System Replacement Analysis AP 400,000 0 0 0 0 0 400,000 State-Owned Buildings Valuation Project AP 60,000 0 0 0 0 0 60,000 ARCS Video Automation and Control Project AP 77,500 0 0 0 0 0 77,500 License Plates and Drivers License Manuals AP 275,000 0 0 0 0 0 275,000 Emergency Communications: Land Mobile Radio Migration AP 1,354,400 0 0 0 14,893,700 0 16,248,100 Electronic Signatures Project AP 100,000 0 0 0 0 0 100,000 Mainframe Improvements, Equipment Replacement, Virus Scanning, AP 0 0 0 0 0 2,181,000 2,181,000 and Metadirectory Development Upgrade Internet and Intranet, and Implement New Network AP 0 0 0 0 0 539,900 539,900 Technology Department of Administration Subtotal 2,366,900 0 0 250,000 14,893,700 3,000,900 20,511,500 Department of Commerce, Community, and Economic Development Language Section: Power Cost Equalization AP 3,734,000 0 0 0 0 3,120,000 6,854,000 Securities Database AP 0 0 0 0 0 300,000 300,000 Operation Renew Hope AP 0 500,000 0 0 30,000,000 0 30,500,000 Community Block Grants AP 0 0