Shrinkage and Cooking Times of Rib Roasts of Beef of Different Grades

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Metropolitan Stocked Beef Cuts

Metropolitan Stocked Beef Cuts R O RIB LOIN U CHUCK N D FLANK BRISKET Click on Beef Cut Section above, this will take you to stocked items for each cut. Click for Grinds Click for Grading and Brand Definitions GRADING and BRANDING SNAKE RIVER FARMS BRAND: Wagyu beef is highly sought after because of it's intense marbling and high percentage of oleaginous unsaturated fat. American-style kobe beef is the result of cross-breeding Japanese Wagyu cattle with continental breeds of cattle, resulting in a marbling that far exceeds the USDA standards. BLACK line of beef has a Japanese marbling score of 6-8, whereas the GOLD line's score is 9-12. Note: Wagyu beef grinds and patties imported from Australia is "Greg Norman Brand". USDA PRIME: Beef is produced from young, well-fed beef cattle. It has abundant marbling. Less than 2% of cattle harvested fall into this category. CERTIFIED ANGUS BEEF BRAND (CAB): Beef selected must adhere to 10 scientific specifications. Upper 2/3 of USDA Choice and above grade only allowed into the program. Modest or higher marbling. Consistent sizing, superior muscling, no dark cutters. To earn the Certified Angus Beef ® brand name, cattle must first be Angus-influenced, with a predominantly solid black coat. only 3 in 10 Angus cattle meet the CAB high standards. GRASS RUN FARMS BRAND: 100% grass-fed beef delivers less total fat, saturated fat, cholesterol and fewer calories to help support a healthy consumer diet. Raised with no antibiotics, hormones or growth promotants, 100% grass-fed beef is available in USDA Choice and Prime grades. -

Breakfast Menu

STEAKS Presidential Choice T-BONE STEAK This hearty portion is sort of “two steaks in one”. It combines the full flavor of the Strip Sirloin, the impeccable tenderness of the Filet and joined together by the famous “T”. This is the steak President Bush preferred when dining in Oklahoma City. We start with the finest Midwest-raised, corn-fed beef. Insisting on USDA Prime or Choice Grades of beef, we offer quality not available at the local grocery store or Cattlemen’s Strip Sirloin Thick, center cut strip sirloin supermarket. Top Sirloin Steak We then slowly age our beef according Cut extra thick for extra goodness from Aged Beef to a closely guarded house secret. This Filet Mignon aging process is impractical to duplicate A choice cut of beef tenderloin with all the sealed in savory at home, and results in a naturally juices, bacon wrapped and broiled to your taste tender, flavorful steak. Rib Eye Steak Perfect center cut from the eye of the rib The “PERFECT STEAK” is then hand- cut (never frozen) in our own butcher Small Filet shop, then broiled over a sharp, hot Cut special for our patrons with very small appetites, wrapped in thick sliced bacon flame from real charcoal that finishes the meat to a sear on the outside—juicy Dinner Steak and tender within! Order your steak Small top-sirloin steak according to the “How Do You Like Your Chopped Sirloin Steak?” chart below, and we’ll serve it up Freshly ground sirloin beef broiled over glowing embers on a platter—hot and juicy with natural steak au jus. -

Latin Touch Prime Rib Worksheet

Latin Touch Prime Rib Worksheet Date: Total Lbs. of Charcoal: Number of Roasts: Ambient (outdoor) temp: A prime rib roast, also known as standing rib roast, is a cut of beef from the rib, one of the nine classic primal cuts of beef. The rib section of a beef is typically comsidered ribs six through twelve, and a prime rib roast may include anywhere from two to seven ribs. A prime is most often roasted "standing" on the rib bones so that the meat does not touch the pan. The rib-eye steak is cut from a standing rib, the bone is removed along with most of the fat and lesser muscles. This recipe can include up to six 4lb prime rib roasts Combine (per roast) 1/4 cup of butter, 1 Tbsp. coarse black pepper, and 1 tsp. Herbes de Provence in a bowl; melt and mix until well blended. Set aside and keep warm. Bring roasts to room temperature (2-3 hours on kitchen counter.) Carefully cut the bones away from the roast in a single piece. Season each roast generously on all sides with kosher salt and a little black pepper. With the point of a sharp knife, poke holes every few inches around the roast, and insert pieces of slivered raw garlic into the holes (optional). Tie the bones back onto the roast with kitchen string. Pre Heating: Position the roasting box is a safe, well ventilated area (but out of direct drafts). If roasting on the lawn, be sure to water the grass well before cooking, just in case. -

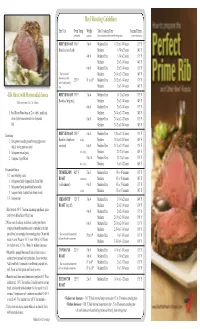

Beef Roasting Guidelines

Beef Roasting Guidelines Beef Cut Oven Temp. Weight Total Cooking Time Internal Temp. (preheated) (pounds) (based on meat directly from the refrigerator) (remove from oven) RIBEYE ROAST 350˚ F 3 to 4 Medium Rare: 1-1/2 to 1-3/4 hours 135˚ F Boneless (small end) Medium: 1-3/4 to 2 hours 145˚ F 4 to 6 Medium Rare: 1-3/4 to 2 hours 135˚ F Medium: 2 to 2-1/4 hours 145˚ F 6 to 8 Medium Rare: 2 to 2-1/4 hours 135˚ F * Tent loosly with Medium: 2-1/4 to 2-1/2 hours 145˚ F aluminum foil half- 325˚ F 8* to 10* Medium Rare: 2-1/2 to 3-1/4 hours 135˚ F way through roasting time. Medium: 3 to 3-3/4 hours 145˚ F -Rib Roast with Horseradish Sauce RIBEYE ROAST 350˚ F 3 to 4 Medium Rare: 1-1/2 to 2 hours 135˚ F Total recipe time: 2-1/2 to 3 hours Boneless (large end) Medium: 2 to 2-1/4 hours 145˚ F 4 to 6 Medium Rare: 2 to 2-1/4 hours 135˚ F 1 beef Ribeye Roast bone-in (2 to 4 ribs), small end, Medium: 2-1/4 to 2-1/2 hours 145˚ F chine (back) bone removed (6 to 8 pounds) 6 to 8 Medium Rare: 2-1/4 to 2-1/2 hours 135˚ F Salt Medium: 2-1/2 to 2-3/4 hours 145˚ F Seasoning: RIBEYE ROAST 350˚ F 4 to 6 Medium Rare: 1-3/4 to 2-1/4 hours 135˚ F 2 tablespoons coarsely ground mixed peppercorns Bone-In (chine bone (2 ribs) Medium: 2-1/4 to 2-3/4 hours 145˚ F (black, white, green and pink) removed) 6 to 8 Medium Rare: 2-1/4 to 2-1/2 hours 135˚ F 1 tablespoon minced garlic (2 to 4 ribs) Medium: 2-1/2 to 3 hours 145˚ F 2 teaspoons vegetable oil 8 to 10 Medium Rare: 2-1/2 to 3 hours 135˚ F (4 to 5 ribs) Medium: 3 to 3-1/2 hours 145˚ F Horseradish Sauce: TENDERLOIN 425˚ F 2 to 3 Medium Rare: 35 to 45 minutes 135˚ F 1/2 cup whipping cream ROAST (center-cut) Medium: 45 to 50 minutes 145˚ F 3 tablespoons finely chopped fresh fennel bulb 3 tablespoons finely grated fresh horseradish (well-trimmed) 4 to 5 Medium Rare: 45 to 55 minutes 135˚ F 1 teaspoon finely chopped fresh fennel fronds (whole) Medium: 55 to 65 minutes 145˚ F 1/8 teaspoon salt SIRLOIN TIP 325˚ F 3 to 4 Medium Rare: 1-3/4 to 2 hours 140˚ F ROAST (cap off) Medium: 2 to 2-1/4 hours 150˚ F 1.Heat oven to 350˚ F. -

Demkota Ranch Beef

“DemKota chooses top of the line beef and that’s what we aim to “Cattle from this part of the country are the best in the world. deliver. High quality, high grading and hard fed cattle; that’s what Farmers and ranchers around here have the genetics down, and all we have and that’s what we provide.” the pieces you need to provide the best beef.” SHAKER VALLEY BRAND 430 6th Street SE. Canton, OH 330-454-1307 SHAKER VALLEY BRAND 430 6th Street SE. Canton, OH 330-454-1307 RIBEYE The rib eye or ribeye is a beef steak from the rib section. The rib section of beef spans from ribs six through twelve. Ribeye steaks are mostly composed of the longissimus dorsi muscle but also contain the complexus and spinalis muscles. #20010 32206 Beef Rib, Ribeye, Lip-on, UP HI-CH #20008 32187 Beef Rib, Ribeye, Lip-on, BI 2x2 HI-CH #20004 33205 Rib, Ribeye, Lip-on, DOWN CH #20030 34205 Beef Rib, Ribeye, Lip-on, DOWN SEL #20024 15206 Beef Rib, Ribeye, Lip-on, UP Legacy NR #14253 N/A Beef Ribeye Steak HI-CH Angus #20079 N/A Beef Ribeye Steak B/I HI-CH Angus STRIP STEAK The strip steak is a cut of beef steaks from the short loin from a cow. It consists of a muscle that does little work, the longissimus, making the meat particularly tender, although not as tender as the nearby psoas major or tenderloin. #20011 32322 Beef Loin, Strip Loin, boneless 0x1 HI-CH #20020 33322 Beef Loin, Strip Loin, boneless 0x1 CH #14093 N/A Beef Strip Steak C/C HI-CH Angus #20083 N/A Beef Strip Steak E/E NW HI-CH Angus SHAKER VALLEY BRAND 430 6th Street SE. -

EC9984 Cooking Tender Cuts of Meat Mabel Doremus

University of Nebraska - Lincoln DigitalCommons@University of Nebraska - Lincoln Historical Materials from University of Nebraska- Extension Lincoln Extension 1950 EC9984 Cooking Tender Cuts of Meat Mabel Doremus Follow this and additional works at: http://digitalcommons.unl.edu/extensionhist Doremus, Mabel, "EC9984 Cooking Tender Cuts of Meat" (1950). Historical Materials from University of Nebraska-Lincoln Extension. 2956. http://digitalcommons.unl.edu/extensionhist/2956 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Extension at DigitalCommons@University of Nebraska - Lincoln. It has been accepted for inclusion in Historical Materials from University of Nebraska-Lincoln Extension by an authorized administrator of DigitalCommons@University of Nebraska - Lincoln. 5 46 . ~5'713 J} qq 11'1 e./ 1950 E.C.9984 COOKING TENDER CUTS OF MEAT Mabel Dor emus The tender cuts of meat, those with a minimum of connective tissue, are cooked by dry-heat methods that cannot be used successfully in cooking the- less t ender cuts, those with any considerable amount of connective tissue. The cuts with the least connective tissue come from those parts of the animal that re ceived the least exercise. These muscles lie along the backbone and may be called the supporting muscles. The general methods of cooking tender cuts of meat by dry heat are (1) roasting, (2) broiling, (3) panbroiling, and (4) pan frying and deep-fat frying. Roasting Any tender cut of beef, ve al, pork or lamb may be roasted. The steps in r oasting are: (1) Season meat with salt and pepper. (2) Place f at side up on r ack in open roasting pan. -

Ohio State University Extension

OHIO STATE UNIVERSITY EXTENSION Grilling Time: Cuts Best for Smoker and Grill When I grill a steak, how can I make sure it’s not tough? Also, I just got a meat smoker as a gift. What cuts of beef would be best for the smoker? Nothing is worse than grilling a steak, enjoying the aroma as it cooks, and then barely being able to cut through it with your best steak knife. The issue probably isn’t your skill on the grill. It’s most likely a bad match of cooking method and cut of beef. Lean cuts of beef — those with little marbling and external fat — are better suited to slow cooking methods, such as smoking. Slow cooking allows connective tissue and muscle fibers to break down. The process tenderizes what otherwise would be a tough chew. Those cuts are from the parts of the animal that work the hardest, the muscles used for walking and locomotion, which have little fat and the most connective tissue. Generally, those cuts are the round, which is at the hindquarters of the animal, and the chuck and brisket, which are at the front of the animal, from the shoulders to the chest. Cuts of meat from these areas, which would be good for your smoker, include: • Brisket • Chuck roast • Arm roasts • Top and bottom round roasts • Tip roasts • Eye round roast • Boneless rump roast In between the round and the chuck are the “middle meats,” which are best for grilling. They tend to have a lot of marbling, which is the little white flecks of fat throughout a piece of meat. -

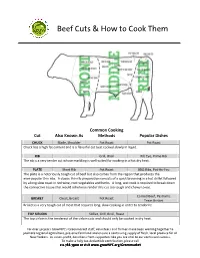

Beef Cuts & How to Cook Them

Beef Cuts & How to Cook Them Common Cooking Cut Also Known As Methods Popular Dishes CHUCK Blade, Shoulder Pot Roast Pot Roast Chuck has a high fat content and is a flavorful cut best cooked slowly in liquid. RIB - Grill, Broil Rib Eye, Prime Rib The rib is a very tender cut whose marbling is well-suited for cooking in a hot dry heat. PLATE Short Rib Pot Roast BBQ Ribs, Pot-Au-Feu The plate is a notoriously tough cut of beef but also comes from the region that produces the ever-popular thin ribs. A classic thin rib preparation consists of a quick browning in a hot skillet followed by a long slow roast in red wine, root vegetables and herbs. A long, wet cook is required to break down the connective tissue that would otherwise render this cut too tough and chewy to eat. Corned Beef, Pastrami, BRISKET Chest, Breast Pot Roast Texas Brisket Brisket is a very tough cut of meat that requires long, slow cooking in order to tenderize. TOP SIRLOIN - Skillet, Grill, Broil, Roast The top sirloin is the tenderest of the sirloin cuts and should only be cooked in dry heat. For over 30 years GrowNYC’s Greenmarket staff, volunteers and farmers have been working together to promote regional agriculture, preserve farmland and ensure a continuing supply of fresh, local produce for all New Yorkers. As a non-profit, donations from supporters like you are vital to our continued success. To make a fully tax-deductible contribution, please call 212.788.7212.788.7212.788.7900212.788.7900 or visit www.growNYC.orgwww.growNYC.org/Greenmarket/Greenmarket Beef Cuts & How to Cook Them Common Cooking Cut Also Known As Methods Popular Dishes TENDERLOIN - Grill, Roast Filet Mignon, Chateaubriand As its name suggests, tenderloin is a very tender cut. -

4-21-17 Wise Notes – Know Your Beef

Tanya Davis Texas A&M AgriLife Extension Service County Extension Agent - FCS 206 S. State Street, Suite A Decatur, Texas 76234 Ph: 940.627.3341 Fax: 940.627.8070 Wise Notes for Consumers Submitted: 4-21-17 Know your Beef Nothing is worse than grilling a steak, enjoying the aroma as it cooks, and then barely being able to cut through it with your best steak knife. The issue probably isn’t your skill on the grill. It’s most likely a bad match of cooking method and cut of beef. The following information from the Texas Beef Council will equip you with knowledge to prepare the perfect meal packed full of nutrition. Beef is an excellent source of 10 essential nutrients, including protein, zinc, vitamin B12, vitamin B6 and niacin. On average, a 3-oz. serving of lean beef is about 150 calories Lean cuts of beef — those with little marbling and external fat — are better suited to slow cooking methods, such as smoking. Slow cooking allows connective tissue and muscle fibers to break down. The process tenderizes what otherwise would be a tough chew. Those cuts are from the parts of the animal that work the hardest, the muscles used for walking and locomotion. Generally, those cuts are the round, which is at the hindquarters of the animal, and the chuck and brisket, which are at the front of the animal, from the shoulders to the chest. Cuts of meat from these areas, which would be good for your smoker, include: brisket; chuck roast; arm roasts; top and bottom round roasts; tip roasts; eye round roast; and boneless rump roast. -

Certified Hereford Beef®

CERTIFIED HEREFORD BEEF® Certified Hereford Beef® is a premium branded-beef program owned by the 7,000 ranchers of the American Hereford Association, the keepers of purebred Hereford genetics since 1881. Our beef is USDA Certified and comes from Hereford and Hereford-English crossbred cattle genetically proven superior in tenderness and taste. • 100% Product of U.S.A. • Medium or fine marbling texture • Consistent, research-proven quality • Minimally processed with no artificial ingredients • Midwestern grain-fed vegetarian diet • No dairy or Brahman influence • Only steer & heifers under 30 months of age • Yield grade 4 or better • USDA registered, certified and graded • Naturally tender, juicy and flavorful beef 20 Riverview Drive Ph: (845) 236-3090 Fax: (845) 236-3096 Marlboro, NY 12542 www.tomiller.com CERTIFIED HEREFORD BEEF® USDA CHOICE Quality, Consistency and Convenience The Certified Hereford Beef® Choice program is a USDA Choice graded product providing naturally tender, juicy and flavorful beef your customers expect. Certified Hereford Beef cuts are recognized for their consistent size and uniform plate presentation, delivering a high-quality beef program that provides an exceptional eating experience. Our premium product gives both chefs and consumers the plate coverage and yield for todays cost-competitive menu. Ribeye, Lip On Case: #21910 4/15 lb. avg. Split: #21911 1/15 lb. avg. Lip-On Ribeye is essentially a Prime Rib roast without the bones. The “lip” that is left on refers to a two-inch (5 cm) piece of meat that is left on at the end of the ribeye muscle. The lip piece is largely fat, with some meat in it. -

A Guide to Beef Cuts Fall 2009 Variety Characteristics Serving Suggestions

Lunds and Byerly’s Lunds and Byerly’s meat department clip-and-keep guide A GUIDE TO BEEF CUTS FALL 2009 VARIETY CHARACTERISTICS SERVING SUGGESTIONS We felt right at home witnessing Double R Ranch’s values in operation because that same integrity and excellence, passion, Rib-Eye Tender with a rich, hearty flavor. and hard work make up the foundation of our values at Lunds Steak Excellent marbling. Grill, broil or pan-sear. and Byerly’s. For us, it’s all about creating sensational shopping experiences Top cooked steaks with: for you and there is nothing as satisfying in this business as selling • Blue cheese One of the more tender cuts of top-quality cuts of meat we know will put a smile on the faces of • Garlic butter beef. Includes a New York Strip your friends and family. Porterhouse • Sautéed mushrooms on one side of the bone and a Steak • A drizzle of olive oil and At our stores there are three different categories of beef to tenderloin on the other. choose from: All-Natural (a leaner beef that comes from cattle that fresh lemon juice have never been given antibiotics or added hormones); Premium Wrap beef tenderloin with Choice (or what I like to call everyday great beef); and Dry-Aged bacon before cooking. Choice (steakhouse quality beef that has been aged 14 days to Beef Fine, melt-in-your mouth increase tenderness and add a rich, nutty flavor). Our Premium Tenderloin texture. Most tender cut of beef. Mild flavor. Choice and Dry-Aged Choice are sourced exclusively from Double Steak R Ranch. -

Beef Or Bouf

BEEF OR BOUF The meat of the bullock, cow or even bull, the best and most expensive meat being that of a bullock about two years old. The quality of beef is very dependent on all sorts of factors, such as the age, breed and sex of the animal and the hanging, storing and cutting up of the joints. It is worth seeking out a butcher who supplies the sort of beef you like. Beef should look fresh and moist, but not watery, with small flecks of fat through the lean. This fat called marbling helps to keep the meet moist and tender during cooking. Choose meat with little gristle between the fat and the lean. Home-killed beef is the choicest, but imported frozen or chilled beef of good quality comes from South Africa, Australia, New-Zealand and other countries. Beef like all meat, is a good source of protein. It also supplies energy, particularly if there is a lot of fat. The amount of fat in different cuts varies considerably and it is impossible to give exact figures for the nutrients. However, it is a good source of B vitamins and a fair source of Iron. 9 13 6 16 15 12 10 18 3 5 7 14 8 17 11 1 2 4 CUTS AND METHODS OF COOKING Cuts of beef vary from country to country, but the best cuts, for roasting, grilling or frying, always come from the rump of the animal, while the proper quality meat, for stewing, braising or casseroling, comes from the forequarter.