UCLA Ufahamu: a Journal of African Studies

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Tracker June/July 2014

KENYA MUSEUM SOCIETY Tracker June/July 2014 Joy Adamson Exhibition Photo by Ebrahim Mwangi, NMK AV Dept Kenya Museum Society P.O. Box 40658 - 00100 Nairobi, Kenya [email protected] www.kenyamuseumsociety.org Tel: 3743808/2339158 (Direct) kenyamuseumsociety Tel: 8164134/5/6 ext 2311 Cell: 0724255299 @museumsociety DRY ASSOCIATES LTD Investment Group Offering you a rainbow of opportunities ... Wealth Management Since 1994 Dry Associates House Brookside Grove, Westlands, Nairobi Tel: +254 (20) 445-0520/1 +254 (20) 234-9651 Mobile(s): 0705799971/0705849429/ 0738253811 June/July 2014 Tracker www.dryassociates.com2 NEWS FROM NMK Joy Adamson Exhibition New at Nairobi National Museum he historic collections of Joy Adamson’s portraits of the peoples of Kenya as well as her botanical and wildlife paintings are once again on view at the TNairobi National Museum. This exhibi- tion includes 50 of Joy’s intriguing portraits and her beautiful botanicals and wildlifeThe exhibition,illustrations funded that are by complementedKMS was officially by related opened objects on May from 19. the muse- um’sVisit ethnographic the KMS shop and where scientific cards collections. featuring some of the portraits are available as is the book, Peoples of Kenya; KMS members are entitled to a 5 per cent dis- count on books. The museum is open seven days a week from 9.30 am to 5.30 pm. Joy Adamson Exhibition Photo by Ebrahim Mwangi, NMK AV Dept June/July 2014 Tracker 3 KMS EASTER SAFARI 18Tsavo - 21 APRIL West 2014 National Park By James Reynolds he Kenya Museum Society's Easter trip saw organiser Narinder Heyer Ta simple but tasty snack in Makindu's Sikh temple, the group entered lead a group of 21 people in 7 vehicles to Tsavo West National Park. -

Kenya Election History 1963-2013

KENYA ELECTION HISTORY 1963-2013 1963 Kenya Election History 1963 1963: THE PRE-INDEPENDENCE ELECTIONS These were the last elections in pre-independent Kenya and the key players were two political parties, KANU and KADU. KADU drew its support from smaller, less urbanized communities hence advocated majimboism (regionalism) as a means of protecting them. KANU had been forced to accept KADU’s proposal to incorporate a majimbo system of government after being pressured by the British government. Though KANU agreed to majimbo, it vowed to undo it after gaining political power. The majimbo constitution that was introduced in 1962 provided for a two-chamber national legislature consisting of an upper (Senate) and lower (House of Representative). The Campaign KADU allied with the African People’s Party (APP) in the campaign. KANU and APP agreed not to field candidates in seats where the other stood a better chance. The Voting Elections were marked by high voter turnout and were held in three phases. They were widely boycotted in the North Eastern Province. Violence was reported in various parts of the country; four were killed in Isiolo, teargas used in Nyanza and Nakuru, clashes between supporters in Machakos, Mombasa, Nairobi and Kitale. In the House of Representative KANU won 66 seats out of 112 and gained working majority from 4 independents and 3 from NPUA, KADU took 47 seats and APP won 8. In the Senate KANU won 19 out 38 seats while KADU won 16 seats, APP won 2 and NPUA only 1. REFERENCE: NATIONAL ELECTIONS DATA BOOK By Institute for Education in Democracy (published in 1997). -

The Unfinished Business of Tom Mboya

A National Reckoning: The Unfinished Business of Tom Mboya By Amol Awuor I Reading Tom Mboya’s memoir “Freedom and After” (1963) is both depressing and irritating. Mboya was one of Kenya’s nationalists, who through his active role in the trade unions in the 1950s, called for an end to British colonial rule. The depressing nature of his memoir is not just about the lofty ideals he so eloquently talked about that never grew wings in post-independent Kenya, but because he became a principal architect in discarding some of those very same ideals. Maybe some of the ideals have been realized in other forms. One could mention a vibrant and freer media (despite accusations of being too cosy to the state) and a robust democracy where citizens now enjoy various rights and liberties. Unfortunately, citizens are still attracted to the idea of ethnic consciousness that often reaches a crescendo, especially during general elections. One sunny Saturday afternoon on July 5, 1969, Mboya walked out of a pharmacy on Government Road, now Moi Avenue, probably with the lotion he had gone to buy stuffed in his coat pockets, only to be stopped by two bullets fired at close range sending him slumping on the pavement. By chance, a health ministry official – Dr Mohamed Rafique Chaudhri – happened to be passing by and heard the commotion, and, recognizing Mboya’s car, rushed to the scene. Images that would later horrify the nation are those of a wounded government minister being wheeled to a waiting ambulance, his left hand slightly hanging on the side, his white shirt spattered with blood and eyes dimmed as Dr Chaudhri raced against time. -

1839 KMS Kenya Past and Present Issue 39.Pdf

Kenya Past and Present Issue 39 Kenya Past and Present Editor Peta Meyer Editorial Board Esmond Bradley Martin Lucy Vigne Bryan Harris Kenya Past and Present is a publication of the Kenya Museum Society, a not-for-profit organisation founded in 1971 to support and raise funds for the National Museums of Kenya. All correspondence should be addressed to: Kenya Museum Society, PO Box 40658, Nairobi 00100, Kenya. Email: [email protected] Website: www.KenyaMuseumSociety.org Statements of fact and opinion appearing in Kenya Past and Present are made on the responsibility of the author alone and do not imply the endorsement of the editor or publishers. Reproduction of the contents is permitted with acknowledgement given to its source. The contribution of articles and photographs is encouraged, however we regret unsolicited material cannot be returned. No category exists for subscription to Kenya Past and Present; it is a benefit of membership in the Kenya Museum Society. Available back issues are for sale at the Society’s offices in the Nairobi National Museum. Any organisation wishing to exchange journals should write to the Head Librarian, National Museums of Kenya, PO Box 40658, Nairobi 00100, Kenya. Kenya Past and Present Issue 39, 2011 Contents KMS highlights 2010-2011.............................................................................3 Patricia Jentz Museum highlights ........................................................................................6 Juliana Jebet Karen Blixen’s first house .............................................................................10 -

Migrated Archives): Ceylon

Colonial administration records (migrated archives): Ceylon Following earlier settlements by the Dutch and Secret and confidential despatches sent to the Secretary of State for the Portuguese, the British colony of Ceylon was Colonies established in 1802 but it was not until the annexation of the Kingdom of Kandy in 1815 FCO 141/2098-2129: the despatches consist of copies of letters and reports from the Governor that the entire island came under British control. and the departments of state in Ceylon circular notices on a variety of subjects such as draft bills and statutes sent for approval, the publication Ceylon became independent in 1948, and a of orders in council, the situation in the Maldives, the Ceylon Defence member of the British Commonwealth. Queen Force, imports and exports, currency regulations, official visits, the Elizabeth remained Head of State until Ceylon political movements of Ceylonese and Indian activists, accounts of became a republic in 1972, under the name of Sri conferences, lists of German and Italian refugees interned in Ceylon and Lanka. accounts of labour unrest. Papers relating to civil servants, including some application forms, lists of officers serving in various branches, conduct reports in cases of maladministration, medical reports, job descriptions, applications for promotion, leave and pensions, requests for transfers, honours and awards and details of retirements. 1931-48 Secret and confidential telegrams received from the Secretary of State for the Colonies FCO 141/2130-2156: secret telegrams from the Colonial Secretary covering subjects such as orders in council, shipping, trade routes, customs, imports and exports, rice quotas, rubber and tea prices, trading with the enemy, air communications, the Ceylon Defence Force, lists of The binder also contains messages from the Prime Minister and enemy aliens, German and Japanese reparations, honours the Secretary of State for the Colonies to Mr Senanyake on 3 and appointments. -

Argreportopt.Pdf

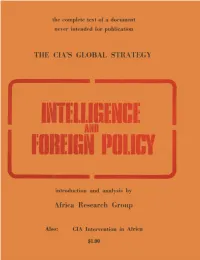

A NECESSARY INTRODUCTIQN PREFACE There are few people wi h any degree of. political literacy anywhere in the world. who have nQt heard about the CIA. Its n oriety is well deserved even if its precise functions in the service of the American Empire often isappear under a cloud of fictional images or crude conspiratorial theories. The Africa Research Gr up is now able to make available the text of a document which helps fill many of the existing ga in understanding the expanded role intelligence agellci~s play in plannin and executing f reign policy objectives. "Intelligence and Foreign Policy," as the document is titled, illumi tes the role of covert action. It enumerates the mechanisms which allow the United States t interfere, with almost routine regularity, in the internal affairs of sovereign nations through ut the world.- We are p~blishing it for many of th~ ,same reason that .American newspapers de ·ed governmel)t censorship to disclose the secret,o igins ,0 the War against the people of Indo hina. Unlike those newspapers, however, we feel the pu~lic ~as more than a "right to know"; it has the duty to struggle against the system which needs and uses the CIA. In addition to the docum nt, the second section of the pamphlet examines CIA inv~lve~ent in a specific setting: its role in the pacification of the Leftist opposition in Kenya, and its promotion of "cultural nationalism" i lother reas of Africa. The larger strategies spoken of in the document here reappear as the dail interventions of U.S. -

Jaramogi Oginga Odinga: the Man Kenya Can Never Forget,Once Upon a Dome,Handshake Manenos!,Handcheque Part II,Tinga!,Three Wise

Jaramogi Oginga Odinga: The Man Kenya Can Never Forget By Dauti Kahura and Bethuel Oduo If Thomas Joseph (TJ) Mboya was the young man that Kenya wanted to forget, Jaramogi Oginga Odinga is the grand old man who Kenya can never forget. Jaramogi and Tom Mboya were both were nationalists of great distinction from the Luo community who as seasoned politicians posed a threat to the founding president Jomo Kenyatta’s autocratic national designs. Tom Mboya died young, by an assassin’s bullet, on July 5, 1969. Jaramogi died an old man, a mzee, at the age of 82 years on January 20, 1994, after having been tormented by both Kenyatta and Daniel arap Moi regimes effectively from 1969 after his fall out with Kenyatta and through the 80s and 90s during iron-fisted Moi’s reign. Jaramogi Oginga Odinga death anniversary on January 20th, twenty-five years since his passing, was marked quietly in a manner that diminishes his immense contribution to the Kenyan national project. If Thomas Joseph (TJ) Mboya was the young man that Kenya wanted to forget, Jaramogi Oginga Odinga is the grand old man who Kenya can never forget No history book on Kenya would be complete without his mention. Jaramogi was the vice president of the nationalist party Kanu when Kenya African Union (Kau) merged with Kenya Independent Movement to form Kanu on May 14, 1960. He was later to become the country’s first Vice President, after Kanu won the 1963 general elections under Kenyatta. When his friend Pio Gama Pinto was killed in 1965, Jaramogi knew he was a targeted man because of his ideological position. -

MAU MAU in NATIONAL and INTERNATIONAL CONSCIOUSNESS by Macharia Munene Introductory Remarks It Is Possible to Look at Mau Mau Co

MAU MAU IN NATIONAL AND INTERNATIONAL CONSCIOUSNESS By Macharia Munene Introductory Remarks It is possible to look at Mau Mau consciousness in terms of two overlapping phases of the Colonial and Post-colonial periods, represented by seminal publications which show the power of books to shape thinking and public consciousness. In the colonial period were Jomo Kenyatta’s 1938 Facing Mount Kenya, the Corfield Report in 1960. In the Post-Colonial period were John Nottingham’s The Myth of Mau Mau soon after independence, and Caroline Elkins’ 2005 Imperial Reckoning/Britain’s Gulag. Each represents a phase of consciousness with regard to the Mau Mau War and can be divided into the following segments: a. The Colonial Setting b. The shock of the Mau Mau War outbreak c. The attempted destruction of Mau Mau Consciousness d. Post-colonial ignoring or effort to rearrange Mau Mau Consciousness e. Limited revival of Consciousness The Attraction The attraction to Mau Mau consciousness is partly because there probably was no challenge to the European colonial state in Africa that captured as much global attention as the Mau Mau War in Kenya against the British and the Algerian War against the French.1 The Mau Mau War was bitter and the benefits did not always accrue to those who bore the brunt of the war.2 A few fighters benefited, but the rest appear to have been neglected. In contrast, those who had opposed the war or supported British colonialists seemingly benefited most, continue to benefit, and a feeling of betrayal cropped up that is often the subject of many debates. -

Kenya: Decolonization, Democracy and the Struggle for Uhuru ______

Meyer 1 Mount Holyoke College Kenya: Decolonization, Democracy and the Struggle for Uhuru _______________________________________________________________________ Kathryn R. Meyer Senior Thesis in International Relations April 27, 2015 Meyer 2 Table of Contents Acknowledgements…………………………………………………………….…………. i Abstract………………………………………………..……………………………...……………. ii Chapter I: Introduction …...………………….……………………………..…………. 1 Research Questions………………………………………………………………. 5 Thesis Organization…………………………………………………..………….. 6 Chapter II: Literature Review………………………………………………………... 10 Terminology …………………………………………..………………………………… 14 Framework of Empire ………………………………….…..………………………….. 16 Primary Source Material ……………………………………..………………………. 17 Methodology …………………………………………………………….……………... 18 Chapter III: British Policies Prior to Independence………………………………... 19 British Land Acts …………………………………………..………………………….. 21 Anti-Colonialism and Nationalism …………………………………..……………… 25 Chapter IV: Decolonization …………………………….……………………………. 31 Chapter V: Independence, 1960-1964………….…………………………………….. 36 Chapter VI: The Kenyatta Era ………………………………………………………. 58 Chapter VII: Arap Moi and 25 Years Post-Independence ………………………… 71 Chapter VIII: Conclusion ……………………………………………………………. 78 Appendix ………………………..………..…………………………………………….. Bibliography ……………………………..…………………………………………….. Meyer i Acknowledgements This project would never have been possible without my initial project advisor, Professor Kavita Datla. From the first ill-prepared proposal in my junior year spring to the creation of my first few chapters -

Patient Safety

PatientPatient SafetySafety -- AfricanAfrican PerspectivesPerspectives Dr Tom Mboya Okeyo MD MPH DSHI Head of Department of Health Standards and Regulatory Services, Kenya Paper presented at World Alliance for Patient Safety Conference, Nairobi 17 Jan 2005 Context: Patient Safety Challenge in Africa • Extreme poverty • Failed health reforms • AIDS Crisis • Humanitarian crisis Health and Economic . Indicators – UNDP Indicators. Kenya Tanzania Uganda Population (2001-2 millions) 31.2 35.6 24.2 GDP (2001 – US$ millions) 11.2 9.3 5.7 Life –Expectancy (1999 –years) 56 44 44.7 Infant Mortality Rate (2001) 74 (79) 104 79 (97) Under-five mortality rate (2001) 112 165 124 Maternal Mortality Rate (1998) 590 530 510 Trends of Health Indicators Negative Negative Negative National Health Expenditure: Consolidated General. Government versus Private expenditure (2001) . CGG Private 25% 75% Source: MOH, 2003 and National Health Accounts (WHO/NHA unit, 28-5-03) NB: CGG= consolidated general government which includes government health expenditure at all government levels as well as expenditure by the National Hospital Insurance Fund. ‘Private’ includes out-of-pocket health expenditure, and health expenditure via Private Prepaid Health Plans, firms and employer-based schemes, NGOs and non-profit institutions. Sources of Health Financing by percentage contribution. to the total national healthcare expenditure per annum in Kenya (2001) . 53.1% 1.6% 16.4% OOP GoK/MoH NHIF PPP 3.6% FEMS NGO/NP 3.9% 21.4% Source: MOH, 2003 and National Health Accounts (WHO/NHA unit, 28-5-03) NB: OOP=out of pocket expenditure; GOK/MOH refers to tax-funded health expenditure by the Government of Kenya/Ministry of Health; NHIF=National Hospital Insurance Fund; PPP=Private Prepaid Health Plans, FEMS= firms and employer-based medical services; NGO/NP= non-government organizations and non-profit institutions. -

Kenyatta and Odinga: the Harbingers of Ethnic Nationalism in Kenya by Dr

Global Journal of HUMAN-SOCIAL SCIENCE: D History Archaeology & Anthropology Volume 14 Issue 3 Version 1.0 Year 2014 Type: Double Blind Peer Reviewed International Research Journal Publisher: Global Journals Inc. (USA) Online ISSN: 2249-460x & Print ISSN: 0975-587X Kenyatta and Odinga: The Harbingers of Ethnic Nationalism in Kenya By Dr. Paul Abiero Opondo Moi University, Kenya Abstract- The paper traces the political problems that Kenya currently faces particularly the country’s inability to construct a united national consciousness, historical relationships that unfolded between the country’s foremost founders, Jomo Kenyatta and Oginga Odinga and the consequences of their political differences and subsequent-fallout in the 1960s. The fall-out saw Kenyatta increasingly consolidating power around himself and a group of loyalists from the Kikuyu community while Odinga who was conceptualized as the symbolic representative of the Luo community was confined to the wilderness of politics. This paper while applying the primordial and essentialist conceptual framework recognizes the determinant role that the two leaders played in establishing the foundations for post-independent Kenya. This is especially true with respect to the negative consequences that their differing perspectives on Kenyan politics bequeathed the country, especially where the evolution of negative ethnicity is concerned. As a result of their discordant political voices in the political arena, there were cases of corruption, the killing of innocent Kenyans in Kisumu in 1969, political assassinations of T J Mboya, Pio Gama Pinto and J M Kariuki among others as this paper argues. GJHSS-D Classification : FOR Code: 160699 KenyattaandOdingaTheHarbingersofEthnicNationalisminKenya Strictly as per the compliance and regulations of: © 2014. -

Pan-African History: Political Figures from Africa and The

Pan-African History Pan-Africanism, the perception by people of African origins and descent that they have interests in common, has been an important by-product of colonialism and the enslavement of African peoples by Europeans. Though it has taken a variety of forms over the two centuries of its fight for equality and against economic exploitation, commonality has been a unifying theme for many Black people, resulting for example in the Back-to-Africa movement in the United States but also in nationalist beliefs such as an African ‘supra-nation’. Pan-African History brings together Pan-Africanist thinkers and activists from the Anglophone and Francophone worlds of the past two hundred years. Included are well-known figures such as Malcolm X, W.E.B. Du Bois, Frantz Fanon, Kwame Nkrumah, and Martin Delany, and the authors’ original research on lesser-known figures such as Constance Cummings-John and Dusé Mohamed Ali reveals exciting new aspects of Pan-Africanism. Hakim Adi is Senior Lecturer in African and Black British History at Middlesex University, London. He is a founder member and currently Chair of the Black and Asian Studies Association and is the author of West Africans in Britain 1900–1960: Nationalism, Pan-Africanism and Communism (1998) and (with M. Sherwood) The 1945 Manchester Pan-African Congress Revisited (1995). Marika Sherwood is a Senior Research Fellow at the Institute of Commonwealth Studies, University of London. She is a founder member and Secretary of the Black and Asian Studies Association; her most recent books are Claudia Jones: A Life in Exile (2000) and Kwame Nkrumah: The Years Abroad 1935–1947 (1996).