BRENTANO STRING Ol}ARTET with JAMES DUNHAM, VIOLA

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

A Chronology of All Artists' Appearances with the Chamber

75 Years of Chamber Music Excellence: A Chronology of all artists’ appearances with the Chamber Music Society of Louisville st 1 Season, 1938 – 1939 Kathleen Parlow, violin and Gunnar Johansen, piano The Gordon String Quartet The Coolidge Quartet The Heermann Trio nd 2 Season, 1939 – 1940 The Budapest String Quartet The Stradivarius Quartet Marcel Hubert, cello and Harold Dart, piano rd 3 Season, 1940 – 1941 Ralph Kirkpatrick, harpsichord and Lois Wann, oboe Belgian PianoString Quartet The Coolidge Quartet th 4 Season, 1941 – 1942 The Trio of New York The Musical Art Quartet The Pro Arte Quartet th 5 Season, 1942 – 1943 The Budapest String Quartet The Coolidge Quartet The Stradivarius Quartet th 6 Season, 1943 – 1944 The Budapest String Quartet Gunnar Johansen, piano and Antonio Brosa, violin The Musical Art Quartet th 7 Season, 1944 – 1945 The Budapest String Quartet The Pro Arte Quartet Alexander Schneider, violin and Ralph Kirkpatrick, harpsichord th 8 Season, 1945 – 1946 The Musical Art Quartet Nikolai Graudan, cello and Joanna Graudan, piano Philip Manuel, harpsichord and Gavin Williamson, harpsichord The Budpest String Quartet th 9 Season, 1946 – 1947 The Louisville Philharmonic String Quartet with Doris Davis, piano The Albeneri Trio The Budapest String Quartet th 10 Season, 1947 – 1948 Alexander Schneider, violin and Ralph Kirkpatrick, harpsichord The Budapest String Quartet The London String Quartet The Walden String Quartet The Albeneri Trio th 11 Season, 1948 – 1949 The Alma Trio -

Nasher Sculpture Center's Soundings Concert Honoring President John F. Kennedy with New Work by American Composer Steven Macke

Nasher Sculpture Center’s Soundings Concert Honoring President John F. Kennedy with New Work by American Composer Steven Mackey to be Performed at City Performance Hall; Guaranteed Seating with Soundings Season Ticket Package Brentano String Quartet Performance of One Red Rose, co-commissioned by the Nasher with Carnegie Hall and Yellow Barn, moved to accommodate bigger audience. DALLAS, Texas (September 12, 2013) – The Nasher Sculpture Center is pleased to announce that the JFK commemorative Soundings concert will be performed at City Performance Hall. Season tickets to Soundings are now on sale with guaranteed seating to the special concert honoring President Kennedy on the 50th anniversary of his death with an important new work by internationally renowned composer Steven Mackey. One Red Rose is written for the Brentano String Quartet in commemoration of this anniversary, and is commissioned by the Nasher (Dallas, TX) with Carnegie Hall (New York, NY) and Yellow Barn (Putney, VT). The concert will be held on Saturday, November 23, 2013 at 7:30 pm at City Performance Hall with celebrated musicians; the Brentano String Quartet, clarinetist Charles Neidich and pianist Seth Knopp. Mr. Mackey’s One Red Rose will be performed along with seminal works by Olivier Messiaen and John Cage. An encore performance of One Red Rose, will take place Sunday, November 24, 2013 at 2 pm at the Sixth Floor Museum at Dealey Plaza. Both concerts will include a discussion with the audience. Season tickets are now available at NasherSculptureCenter.org and individual tickets for the November 23 concert will be available for purchase on October 8, 2013. -

National Endowment for the Arts Annual Report 1996

TO THE CONGRESS OF THE UNITED STATES: It is my pleasure to transmit herewith the Annual Report of the National Endowment for the Arts for the fiscal year 1996. One measure of a great nation is the vitality of its culture, the dedication of its people to nurturing a climate where creativity can flourish. By support ing our museums and theaters, our dance companies and symphony orches tras, our writers and our artists, the National Endowment for the Arts provides such a climate. Look through this report and you will find many reasons to be proud of our Nation’s cultural life at the end of the 20th century and what it portends for Americans and the world in the years ahead. Despite cutbacks in its budget, the Endowment was able to fund thou sands of projects all across America -- a museum in Sitka, Alaska, a dance company in Miami, Florida, a production of Eugene O’Neill in New York City, a Whisder exhibition in Chicago, and artists in the schools in all 50 states. Millions of Americans were able to see plays, hear concerts, and participate in the arts in their hometowns, thanks to the work of this small agency. As we set priorities for the coming years, let’s not forget the vita! role of the National Endowment for the Arts must continue to play in our national life. The Endowment shows the world that we take pride in American culture here and abroad. It is a beacon, not only of creativity, but of free dom. And let us keep that lamp brightly burning now and for all time. -

Brentano String Quartet

“Passionate, uninhibited, and spellbinding” —London Independent Brentano String Quartet Saturday, October 17, 2015 Riverside Recital Hall Hancher University of Iowa A collaboration with the University of Iowa String Quartet Residency Program with further support from the Ida Cordelia Beam Distinguished Visiting Professor Program. THE PROGRAM BRENTANO STRING QUARTET Mark Steinberg violin Serena Canin violin Misha Amory viola Nina Lee cello Selections from The Art of the Fugue Johann Sebastian Bach Quartet No. 3, Op. 94 Benjamin Britten Duets: With moderate movement Ostinato: Very fast Solo: Very calm Burlesque: Fast - con fuoco Recitative and Passacaglia (La Serenissima): Slow Intermission Quartet in B-flat Major, Op. 67 Johannes Brahms Vivace Andante Agitato (Allegretto non troppo) Poco Allegretto con variazioni The Brentano String Quartet appears by arrangement with David Rowe Artists www.davidroweartists.com. The Brentano String Quartet record for AEON (distributed by Allegro Media Group). www.brentanoquartet.com 2 THE ARTISTS Since its inception in 1992, the Brentano String Quartet has appeared throughout the world to popular and critical acclaim. “Passionate, uninhibited and spellbinding,” raves the London Independent; the New York Times extols its “luxuriously warm sound [and] yearning lyricism.” In 2014, the Brentano Quartet succeeded the Tokyo Quartet as Artists in Residence at Yale University, departing from their fourteen-year residency at Princeton University. The quartet also currently serves as the collaborative ensemble for the Van Cliburn International Piano Competition. The quartet has performed in the world’s most prestigious venues, including Carnegie Hall and Alice Tully Hall in New York; the Library of Congress in Washington; the Concertgebouw in Amsterdam; the Konzerthaus in Vienna; Suntory Hall in Tokyo; and the Sydney Opera House. -

The Seventh Season Being Mendelssohn CHAMBER MUSIC FESTIVAL and INSTITUTE July 17–August 8, 2009 David Finckel and Wu Han, Artistic Directors

The Seventh Season Being Mendelssohn CHAMBER MUSIC FESTIVAL AND INSTITUTE July 17–August 8, 2009 David Finckel and Wu Han, Artistic Directors Music@Menlo Being Mendelssohn the seventh season july 17–august 8, 2009 david finckel and wu han, artistic directors Contents 3 A Message from the Artistic Directors 5 Welcome from the Executive Director 7 Being Mendelssohn: Program Information 8 Essay: “Mendelssohn and Us” by R. Larry Todd 10 Encounters I–IV 12 Concert Programs I–V 29 Mendelssohn String Quartet Cycle I–III 35 Carte Blanche Concerts I–III 46 Chamber Music Institute 48 Prelude Performances 54 Koret Young Performers Concerts 57 Open House 58 Café Conversations 59 Master Classes 60 Visual Arts and the Festival 61 Artist and Faculty Biographies 74 Glossary 76 Join Music@Menlo 80 Acknowledgments 81 Ticket and Performance Information 83 Music@Menlo LIVE 84 Festival Calendar Cover artwork: untitled, 2009, oil on card stock, 40 x 40 cm by Theo Noll. Inside (p. 60): paintings by Theo Noll. Images on pp. 1, 7, 9 (Mendelssohn portrait), 10 (Mendelssohn portrait), 12, 16, 19, 23, and 26 courtesy of Bildarchiv Preussischer Kulturbesitz/Art Resource, NY. Images on pp. 10–11 (landscape) courtesy of Lebrecht Music and Arts; (insects, Mendelssohn on deathbed) courtesy of the Bridgeman Art Library. Photographs on pp. 30–31, Pacifica Quartet, courtesy of the Chamber Music Society of Lincoln Center. Theo Noll (p. 60): Simone Geissler. Bruce Adolphe (p. 61), Orli Shaham (p. 66), Da-Hong Seetoo (p. 83): Christian Steiner. William Bennett (p. 62): Ralph Granich. Hasse Borup (p. 62): Mary Noble Ours. -

The Brentano String Quartet

The Brentano String Quartet Guest Artist Series Katzin Concert Hall I February 5th, 20161 7:30 P.M. Program Selections from "Art of the Fugue" J. S. Bach (1685 - 1750) INTERMISSION String Quartet in F sharp minor, Op. 50, No. 4 Franz Josef Haydn Allegro spirituoso (1732-1809) Andante Menuetto (Poco Allegretto) Finale Fuga (Allegro moderato) Grosse Fuge in B-flat major, opus 133 Ludwig van Beethoven (1770-1827) The Brentano String Quartet Mark Steinberg, violin Serena Canin, violin Misha Amory, viola Nina Lee, cello A511. Herberger Institute FOR DESIGN AND THE ARTS ARIZONA STATE UNIVERSITY School of Music Since its inception in 1992, the Brentano String Quartet has appeared throughout the world to popular and critical acclaim. "Passionate, uninhibited and spellbinding," raves the London Independent; the New York Times extols its "luxuriously warm sound [and] yearning lyricism." In 2014, the Brentano Quartet succeeded the Tokyo Quartet as Artists in Residence at Yale University, departing from their 14 year residency at Princeton University. The Quartet also currently serves as the collaborative ensemble for the Van Cliburn International Piano Competition. The Quartet has performed in the world's most prestigious venues, including Carnegie Hall and Alice Tully Hall in New York; the Library of Congress in Washington; the Concertgebouw in Amsterdam; the Konzerthaus in Vienna; Suntory Hall in Tokyo; and the Sydney Opera House. The Quartet had its first European tour in 1997, and was honored in the U.K. with the Royal Philharmonic A ward for Most Outstanding Debut. The Brentano Quartet is known for especially imaginative projects combining old and new music, such as "Fragments: Connecting Past and Present" and "Bach Perspectives." Among the Quartet's latest collaborations with contemporary composers is a new work by Steven Mackey, "One Red Rose," commemorating the 50th anniversary of the assassination of President John F. -

Concert: Chamber Music of Steven Mackey Steven Mackey

Ithaca College Digital Commons @ IC All Concert & Recital Programs Concert & Recital Programs 4-17-2011 Concert: Chamber Music of Steven Mackey Steven Mackey Follow this and additional works at: http://digitalcommons.ithaca.edu/music_programs Part of the Music Commons Recommended Citation Mackey, Steven, "Concert: Chamber Music of Steven Mackey" (2011). All Concert & Recital Programs. 155. http://digitalcommons.ithaca.edu/music_programs/155 This Program is brought to you for free and open access by the Concert & Recital Programs at Digital Commons @ IC. It has been accepted for inclusion in All Concert & Recital Programs by an authorized administrator of Digital Commons @ IC. Chamber Music of Steven Mackey The 2010-2011 Husa Visiting Professor of Composition Hockett Family Recital Hall Sunday, April 17, 2011 4:00 p.m. Indigenous Instruments Jacqueline Christen*, flute/piccolo Adam Butalewicz*, clarinet Kate Goldstein*, violin Nathan Gulla*, piano Richard Faria**, conductor Measures of Turbulence Eric Pearson, Matt Gillen, Nick Throop, Nick Malishak, Russ Knifin, guitar Dave Moore, Scott Card, electric guitar Sam Verneuille, electric bass Chun-Ming Chen, conductor Intermission Gaggle and Flock Gaggle Flock Nicholas DiEugenio**, Susan Waterbury**, Isaac Shiman, Sadie Kenny, violin Zachary Slack, Max Aleman, viola Elizabeth Simkin**, Peter Volpert, cello Jeffery Meyer**, conductor * Ithaca College Alumni ** Ithaca College Faculty Biography Steven Mackey Steven Mackey was born in 1956 to American parents stationed in Frankfurt, Germany. His first musical passion was playing the electric guitar, in rock bands based in northern California. He later discovered concert music and has composed for orchestras, chamber ensembles, dance, and opera. He regularly performs his own works, including two electric guitar concertos and numerous solo and chamber works, and is also active as an improvising musician and performs with his band Big Farm. -

The Ninth Season Through Brahms CHAMBER MUSIC FESTIVAL and INSTITUTE July 22–August 13, 2011 David Finckel and Wu Han, Artistic Directors

The Ninth Season Through Brahms CHAMBER MUSIC FESTIVAL AND INSTITUTE July 22–August 13, 2011 David Finckel and Wu Han, Artistic Directors Music@Menlo Through Brahms the ninth season July 22–August 13, 2011 david finckel and wu han, artistic directors Contents 2 Season Dedication 3 A Message from the Artistic Directors 4 Welcome from the Executive Director 4 Board, Administration, and Mission Statement 5 Through Brahms Program Overview 6 Essay: “Johannes Brahms: The Great Romantic” by Calum MacDonald 8 Encounters I–IV 11 Concert Programs I–VI 30 String Quartet Programs 37 Carte Blanche Concerts I–IV 50 Chamber Music Institute 52 Prelude Performances 61 Koret Young Performers Concerts 64 Café Conversations 65 Master Classes 66 Open House 67 2011 Visual Artist: John Morra 68 Listening Room 69 Music@Menlo LIVE 70 2011–2012 Winter Series 72 Artist and Faculty Biographies 85 Internship Program 86 Glossary 88 Join Music@Menlo 92 Acknowledgments 95 Ticket and Performance Information 96 Calendar Cover artwork: Mertz No. 12, 2009, by John Morra. Inside (p. 67): Paintings by John Morra. Photograph of Johannes Brahms in his studio (p. 1): © The Art Archive/Museum der Stadt Wien/ Alfredo Dagli Orti. Photograph of the grave of Johannes Brahms in the Zentralfriedhof (central cemetery), Vienna, Austria (p. 5): © Chris Stock/Lebrecht Music and Arts. Photograph of Brahms (p. 7): Courtesy of Eugene Drucker in memory of Ernest Drucker. Da-Hong Seetoo (p. 69) and Ani Kavafian (p. 75): Christian Steiner. Paul Appleby (p. 72): Ken Howard. Carey Bell (p. 73): Steve Savage. Sasha Cooke (p. 74): Nick Granito. -

Brentano String Quartet

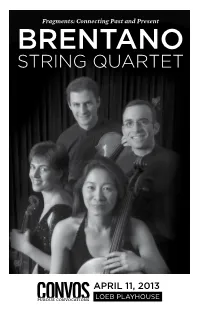

Fragments: Connecting Past and Present BRENTANO STRING QUARTET APRIL 11, 2013 LOEB PLAYHOUSE PROGRAM FRAGMENTS: CONNECTING PAST AND PRESENT. Six unfinished compositions from the past inspire contemporary composers to create new works. Marian Tropes (2010) CHARLES WUORINEN (b. 1938) Quartet in c minor, D703 (unfinished) Allegro Assai Andante (fragment) FRANZ SCHUBERT (1797-1828) Fra(nz)g-mentation (2010) BRUCE ADOLPHE (b. 1955) Contrapunctus XVIII (unfinished) from The Art of Fugue J.S. Bach (1685-1750) Reflections on the Theme B-A-C-H(2002) SOFIA GUBAIDULINA (b. 1931) -INTERMISSION- With respect to the musicians and your fellow patrons, we request your participation in the tradition of withholding applause between movements of a selection. BRENTANO STRING QUARTET Quartet in D Minor, Op. 103 Andante grazioso Menuet ma non troppo presto JOSEF HAYDN (1732-1809) Finale: Presto (2011) FRANZ SCHUBERT (1797-1828) Quartet Movement Allegretto BDMITRI SHOSTAKOVICH (1906-1975) From the Fifth Book (2011) STEPHEN HARTKE (b. 1952) Quartet Fragment in eminor, K417d W.A. MOZART (1756-1791) Mozart Effects(2011) VIJAY IYER (b. 1971) The Brentano String Quartet appears by arrangement with David Rowe Artists / www.davidroweartists.com The Brentano String Quartet record for AEON (distributed by Allegro Media Group) www.brentanoquartet.com MARK STEINBERG SERENA CANIN Violin Violin MISHA AMORY NINA MARIA LEE Viola Cello ABOUT THE BRENTANO STRING QUARTET Since its inception in 1992, the Brentano String Quartet has appeared throughout the world to popular and -

The Brentano String Quartet (Usa)

THE BRENTANO STRING QUARTET (USA) FRIDAY, NOVEMBER 1, 2019 • 8PM THE CLARICE SMITH PERFORMING ARTS CENTER ABOUT THE PROGRAM Quartet in E flat major, K. 428 Wolfgang Amadeus Mozart Note written by Misha Amory When I was younger I aspired to be a serious composer. It seemed to me that a good approach to composing would involve choosing one of the received forms – sonata allegro form, for example – and, having devised a couple of striking melodic ideas, fit them into that form and follow the rules for getting from one structural point to the next, while maybe, I don’t know, throwing in two or three unexpected twists and turns along the way. Studying the music of great composers, I often felt that I could detect a similar creative system in use, where, on a very good day, I could imagine myself coming up with something nearly that good using my assembly method. But, then there was music which seemed to defy this logic, where I was unable to imagine a method that would summon this music into being. Where my approach to writing music was like taking a boxy, pre-fab house, cutting some doorways between the rooms and populating the rooms with furniture and things, this other music evoked the contemplation of lovely objects, the exploration of unknown passageways and then, eventually, a realisation that the form itself, an airy mansion that contained these things, had risen up around us, called into being by its contents. Very often, the composer of that music turned out to be Mozart. -

Juilliard String Quartet Today, with (L to R) Smirnoff, Krosnick, Rhodes and Copes

Opposite page: The Juilliard String Quartet today, with (l to r) Smirnoff, Krosnick, Rhodes and Copes. Inset: In the late 1950s with Hillyer, Mann, Isidore Cohen and Claus Adam. he Juilliard String Quartet is arguably America’s best-known chamber music ensemble—and certainly one of the most admired. And although its current members are only in middle age, the quartet itself cannot escape the adjective “venerable.” Violinist Robert Mann founded the T group in 1946 with violist Raphael Hillyer, cellist Arthur Winograd and the late violinist Robert Koff. With Mann in the first violinist’s chair for an amazing fifty of the ensemble’s sixty-one years— and with remarkably few other personnel changes—the quartet has performed and recorded, taught aspiring chamber musicians, championed American com- posers, and introduced at least two generations of concertgoers to the European masterworks. In 1962—with Isidore Cohen as second violinist and Claus Adam as cellist—the Juilliard succeeded the legendary Budapest String Quartet as ensemble-in-residence at the Library of Congress and went on to perform there often broadcasting live concerts nationwide for 40 years. In recognition of its extraordinary contribution to the nation’s cultural #life, the Juilliard String Quartet has been named the 2008 recipient of Chamber Music America’s Richard J. Bogomolny National Service Award, the organization’s highest honor. On January 6, 2008, founding members Mann, Winograd, and Hillyer will #join Earl Carlyss (violin II from 1966 to 1986) and the current quartet— violinists Joel Smirnoff and Ronald Copes, violist Samuel Rhodes, and cellist Joel Krosnick—to receive the award at CMA’s Thirtieth Anniversary National Conference in New York City. -

The Glimmerglass Festival

A 2017 Guide FEATURE ARTICLE Training Opera’s Next Generation A Tale of Two Festivals April 2017 Festivals Editor’s Note In our largest and most varied Guide to Summer Festivals yet, we focus on a common thread: training the next generation of performers and the artistic personnel who support them. At many festivals, young artists receive private lessons, coaching sessions, master classes, or all of the above during the day. By night they are either performing, observing the seasoned pros who train them by day, or a combination of the two. But honing or developing the skills of tomorrow’s generation of musicians is only part of the equation. It’s summertime, after all, and while the living may not exactly be “easy,” it’s certainly a lot more relaxed than during the season or school year. Consider the difference between waiting in the green-room line post-concert A 2017 Guide to shake the maestro’s hand vs. running into him in the festival cafeteria line, or at the local pub after the concert, or on a morning jog. Such is the kind of cross-fertilization for which festivals are known, and one of the reasons they are such ideal settings for rising artists. Sometimes the trainees are fully integrated into the schedule, such as at the Santa Fe Opera, where young artists are featured, often in leading roles. Sometimes they work independently of the main event, such as at Tanglewood, where the Tanglewood Music Center Orchestra, for instance, is comprised entirely of TMC Fellows and plays its own concerts, alongside the center-stage Boston Symphony Orchestra (whose members form much of the faculty).