No1 Fi'. 0, 15'418

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Steam Locomotive Table, V1

The Steam Locomotive Table, v1 If you’re reading this; you either like steam trains, or want to know more about them. Hopefully, either way, I can scratch your itch with this; a set of randomizer/dice-roll tables of my own making; as inspired by some similar tables for tanks and aircrafts. Bear with me, I know not everyone knows the things I do, and I sure know I don’t know a lot of things other train enthusiasts do; but hopefully the descriptions and examples will be enough to get anyone through this smoothly. To begin, you’ll either want a bunch of dice or any online dice-rolling/number generating site (or just pick at your own whim); and somewhere or something to keep track of the details. These tables will give details of a presumed (roughly) standard steam locomotive. No sentinels or other engines with vertical boilers; no climax, shay, etc specially driven locomotives; are considered for this listing as they can change many of the fundamental details of an engine. Go in expecting to make the likes of mainline, branchline, dockyard, etc engines; not the likes of experiments like Bulleid’s Leader or specific industry engines like the aforementioned logging shays. Some dice rolls will have uneven distribution, such as “1-4, and 5-6”. Typically this means that the less likely detail is also one that is/was significantly less common in real life, or significantly more complex to depict. For clarity sake examples will be linked, but you’re always encouraged to look up more as you would like or feel necessary. -

O-Steam-Price-List-Mar2017.Pdf

Part # Description Package Price ======== ================================================== ========= ========== O SCALE STEAM CATALOG PARTS LIST 2 Springs, driver leaf........................ Pkg. 2 $6.25 3 Floor, cab and wood grained deck............. Ea. $14.50 4 Beam, end, front pilot w/coupler pocket...... Ea. $8.00 5 Beam, end, rear pilot w/carry iron.......... Ea. $8.00 6 Bearings, valve rocker....................... Pkg.2 $6.50 8 Coupler pockets, 3-level, for link & pin..... Pkg. 2 $5.75 9 Backhead w/fire door base.................... Ea. $9.00 10 Fire door, working........................... Ea. $7.75 11 Journal, 3/32" bore.......................... Pkg. 4. $5.75 12 Coupler pockets, small, S.F. Street Railway.. Pkg.2 $5.25 13 Brakes, engine............................... Pkg.2 $7.00 14 Smokebox, 22"OD, w/working door.............. Ea. $13.00 15 Drawbar, rear link & pin..................... Ea. $5.00 16 Handles, firedoor............................ Pkg.2. $5.00 17 Shelf, oil can, backhead..................... Ea. $5.75 18 Gauge, backhead, steam pressure.............. Ea. $5.50 19 Lubricator, triple-feed, w/bracket, Seibert.. Ea. $7.50 20 Tri-cock drain w/3 valves, backhead.......... Ea. $5.75 21 Tri-cock valves, backhead, (pl. 48461)....... Pkg. 3 $5.50 23 Throttle, nonworking......................... Ea. $6.75 23.1 Throttle, non working, plastic............... Ea. $5.50 24 Pop-off, pressure, spring & arm.............. Ea. $6.00 25 Levers, reverse/brake, working............... Kit. $7.50 26 Tri-cock drain, less valves.................. Ea. $5.75 27 Seat boxes w/backs........................... Pkg.2 $7.50 28 Injector w/piping, Penberthy,................ Pkg.2 $6.75 29 Oiler, small hand, N/S....................... Pkg.2 $6.00 32 Retainers, journal........................... Pkg. -

Locomotives and Views of Mauch Chunk Contact Photographs and Negatives 1969.092

Locomotives and views of Mauch Chunk contact photographs and negatives 1969.092 This finding aid was produced using ArchivesSpace on September 14, 2021. Description is written in: English. Describing Archives: A Content Standard Audiovisual Collections PO Box 3630 Wilmington, Delaware 19807 [email protected] URL: http://www.hagley.org/library Locomotives and views of Mauch Chunk contact photographs and negatives 1969.092 Table of Contents Summary Information .................................................................................................................................... 3 Historical Note ............................................................................................................................................... 3 Scope and Content ......................................................................................................................................... 4 Administrative Information ............................................................................................................................ 5 Related Materials ........................................................................................................................................... 6 Controlled Access Headings .......................................................................................................................... 6 Collection Inventory ....................................................................................................................................... 6 Rolling stock ............................................................................................................................................... -

Reference Guide – 2008 Waybill Sample

REFERENCE GUIDE FOR THE 2008 SURFACE TRANSPORTATION BOARD CARLOAD WAYBILL SAMPLE Business Services Division August 31, 2009 This publication is produced under contract to the Surface Transportation Board Contract DFTR 53-02-C-00073 TABLE OF CONTENTS SECTION 1 Summary of 2008 Waybill Processing.............................................................. 1 Waybills of US, Canadian & Mexican Origin ........................................................................................................... 5 Waybills of US Origin ............................................................................................................................................. 10 Waybills of Canadian Origin ................................................................................................................................... 15 Waybills of Mexican Origin .................................................................................................................................... 20 SECTION 2 Error Analysis and Corrective Action ........................................................... 26 2008 Reporting Railroads ........................................................................................................................................ 35 Proxy Equipment Types for the 2008 Carload Waybill Sample ............................................................................. 36 SECTION 3 Data Exceptions ................................................................................................ 37 Railinc Waybill -

February Final.Indd

RAIL REPORT February 2010 • NO. 598 Rocky Mountain Railroad Club • Rocky Mountain Railroad Historical Foundation Steam Locomotives of the Katy Railroad Presented by John Charles February 9th, 2010 • 7:30 PM Steam Locomotives of the Katy Railroad is a digital program on the history and development of steam locomotives on the Missouri Kansas Texas (Katy) Railroad. Covering everything from the 4-4-0s of 1880 to the last use of steam in the early 1950s, the program will include roster shots and a lot of action photos as well. The program ends with a selection of excellent color action shots by Emery Gulash. Please come join us for an enjoyable, educational evening at Christ Episcopal Church at 2950 South University Boulevard, University at Bates, where there is plen- ty of off street parking at the rear of the complex. Enter into Barnes Hall, where we hold the monthly meetings, on the mid-south side doors. Please bring a guest. All programs are intended to provide an educational experience on railroading. The general public is welcome to attend. There is no charge for this meeting. Please note: Due to scheduling changes at the Church, beginning in April our meeting night will change to the second Wednesday of the month. RMRRC Calendar March 9th Meeting, and PeruRail program. April 14th Second Wednesday Meeting, with program to be announced soon. May 12th Second Wednesday Meeting, with program to be announced soon. Due to circumstances beyond our control, programs and dates are subject to change without notice. Please contact Pat Mauro at [email protected] or phone 303-838-7740 with program ideas. -

Forgotten Railroads That Transformed Winthrop, Orient Heights, and Revere Beach, Massachusetts by William Lieberman

The history of railroads in the Town of Winthrop, Massachusetts and its neighboring communities is recounted. Details are provided about the railroads' routes, equipment, service, and corporate structures. Included is a description of how these railroads fostered the development of Boston's Inner North Shore. THE TRAIN ON THE BEACH: Forgotten Railroads that Transformed Winthrop, Orient Heights, and Revere Beach, Massachusetts By William Lieberman Order the book from the publisher Booklocker.com https://www.booklocker.com/p/books/9383.html?s=pdf or from your favorite neighborhood or online bookstore. The Train on the Beach Forgotten Railroads that Transformed Winthrop, Orient Heights, and Revere Beach, Massachusetts William Lieberman Copyright © 2017-2020 William Lieberman ISBN: 978-1-63492-183-1 All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, recording, or otherwise, without the prior written permission of the author. Published by BookLocker.com, Inc., St. Petersburg, Florida, U.S.A. Printed on acid-free paper. BookLocker.com, Inc. Third Edition 2020 Dedicated To Donald Simonini Boston, Winthrop & Point Shirley Narrow Gauge Train, c. 1882 The train crew poses at the end of the line, probably at Short Beach (today’s Yirrell Beach) in Winthrop. The view is apparently looking southwest, with Boston Harbor to the right. Shirley Street is visible just beyond the front of the locomotive and a small bit of Point Shirley barely perceptible behind the rear of the train. Plainly evident are the sand and beach grass that provided a none-too-stable support for the trackway. -

Russia's Next Generation Railcars

45-CXP-A153 Russia’s Next Generation Railcars An Interactive Qualifying Project Report Submitted to the Faculty of the WORCESTER POLYTECHNIC INSTITUTE in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the Degree of Bachelor of Science Sponsoring Agency: Brunswick Rail Submitted to: On-Site Liaison: Richard Sultanov, Director of Marketing Project Advisor: R. Creighton Peet, WPI Professor Project Co-advisor: Oleg Pavlov, WPI Professor Submitted by: Brianna Fogal & Corin Rypkema Date of Submission: October 15th, 2015 This report represents the work of two WPI undergraduate students submitted to Worcester Polytechnic Institute as evidence of completion of a degree requirement. WPI routinely publishes these reports on its web site without editorial or peer review. i Abstract Brunswick Rail must replace nearly 8,000 railcars as they reach the end of their service life, with either existing standard railcars or New Generation Railcars (NGRs). Russia’s railcar fleet as a whole faces a similar dilemma. We determined the potential effects of NGRs on railcar leasing by conducting a cost-benefit analysis and through discussions with industry experts. While NGRs could be beneficial to the rail industry, Brunswick Rail will find purchasing these railcars difficult due to the current economic environment. ii Acknowledgements Our team would like to acknowledge the following people and organizations for the support and contributions to this Interactive Qualifying Project: Brunswick Rail for sponsoring this project and providing a productive work environment. Richard Sultanov for his guidance in the direction of our project, connecting us to all interviewees, and his valuable knowledge in the rail industry. Anastasia Ermolova for guiding us during site visits. -

A. Introduction Page 1

A. Introduction Page 1 From this ……………………………..to this The Mason Bogie is one of those iconic North American locomotives that I have wanted to have running on my Seath Valley Railroad for years. Then along came grandchild number five and as I have a loco named after each of the other grandchildren I no longer had an excuse for delaying the start of the project. Initially I had looked at converting an LGB Mogul but could not bring myself to parting with that amount of money to cut it apart to build my Mason Bogie. My current LGB Mogul is a fantastic runner but is not too easy a model to disassemble, and there was no way I could touch that as grandson Daniel would have been more than upset. The Piko Mogul is a much less detailed loco than the LGB model but none the less it has the correct wheel configuration of 2-6-0, appeared to be easier to take apart and was about half the cost of the LGB model. So I thought “Hey Ho give it a go” so I took the plunge and bought a new model of the Piko loco. Upon opening the box I was, as usual with any new purchase, pleased to see it had arrived undamaged. The model is heavy and yes, it is plain, but looked as good as the press ‘photo’s indicated. Putting the loco on the track for a test run I was pleased that it ran so well. The plastic wheels on the tender were crying out to be replaced with metal one’s so a rapid replacement with a set of metal wheels from one of my freight cars effected an immediate improvement, both visually and performance wise. -

THE A1 STEAM LOCOMOTIVE TRUST IS YOUR LEGACY I 60163: TORNADO’S 10TH BIRTHDAY APPEAL by Mark Allatt

3403 ANON Recreating Gresley’s last design THE COMMUNICATION CORD No. 55 Autumn 2019 Warren Hannabuss Warren Blackpool illuminations! Tornado prepares to leave the town with the returning ‘Illuminati’ on 2nd November. 1 All Convention photos Mandy Grant All Convention CONTENTS 2019 CONVENTION PAGE 1 by Graham Langer 'The Illuminati' PAGE 2 2019 Convention The A1 Steam Locomotive Trust’s 2019 Contents Convention was again held at the Kings PAGE 5 Hotel in Darlington and was, as ever, very Editorial well supported with over 180 people able RAF 25th Anniversary Dinner PAGE 6 to attend. President of the Trust, David New Trustee appointed to the Board Champion, opened proceedings, welcoming A1 engineering report Covenantors and introducing the team PAGE 7 before announcing the appointment of 'The Aberdonian' Steve Davies, MBE, to the Board as a new PAGE 8 Trustee (see separate news item on page 6). Tornado on Tour- Huw Parker then updated the assembled ‘The Aberdonian’ RAF 25TH PAGE 10 company with a review of recent tours and ANNIVERSARY Tornado on Tour- activity with Tornado. Despite some small DINNER ‘The North Briton’ challenges it has proved to have been a David Champion. PAGE 11 successful summer season for No. 60163 Keeping Tornado on the tracks and he highlighted the continuing close will continue to evolve over the coming Tornado Tour Diary 2019 PAGE 12 relationship with the crew of HMS Prince months including our first outings with The Tornado on Tour- of Wales, some of whom have been able to Railway Touring Company and a return ‘The Pennine Explorer’ join us on ‘The Aberdonian’ this year. -

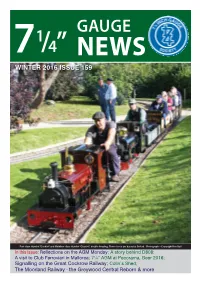

Winter 2016 Issue 159

GAUGE 1 7 /4” NEWS WINTER 2016 ISSUE 159 Port class Hunslet "Cackler" and Mainline class Hunslet "Charles", double heading. These locos are based at Oxford. Photograph – Copyright Ken Bull In this Issue: Reflections on the AGM Monday; A story behind D808; A visit to Club Ferroviari in Mallorca; 7¼” AGM at Pecorama, Beer 2016; Signalling on the Great Cockrow Railway; Colin’s Shed; The Moorland Railway - the Greywood Central Reborn & more In this Issue Awards presented at the AGM 2016 4 Society stand at the Midlands Exhibition 5 Letters to the Editor 5 Reflections on the AGM Monday 6 The Moorland Railway - the Greywood Central reborn 8 A story behind D808 11 Colin’s Shed 14 Society AGM at Pecorama, Beer 2016 18 Signalling on the Great Cockrow Railway 22 A visit to Club Ferroviari in Mallorca 25 The Ashmanhaugh Ramp 26 Book Review 26 Obituary - Alan Priest 27 The Goods Yard 28 Members’ Notices 38 7¼” Gauge Society Ltd - Information The Society’s website is: www.sevenandaquarter.org President: Assistant Secretary: AGM (2019) Coordinator: Brian Reading, 12 Belmore Close, Thorpe Gilly Rainer, 15 Chaucer Road, George White St. Andrew, Norwich, Norfolk, NR7 0PS. Milton Keynes, Buckinghamshire, MK3 5AH Tel: 01749 674489 Tel: (01603) 434915 Tel: (01908) 366198 Email: [email protected] Email: [email protected] COMMITTEE/DIRECTORS Committee Member: Chairman: Membership Secretary: Nigel Freestone, 11 Kingfisher Drive, Frank Cooper, 47 Holmes Road, Frank Cooper, 47 Holmes Road, Durrington, Wiltshire, SP4 8LJ Stickney, PE22 8AZ Stickney, PE22 8AZ Tel: 01205 481197 Tel: 01205 481197 Email: [email protected] Email: [email protected] 1 MEMBERSHIP Secretary: Editor 7 ⁄4” Gauge News: of The 7¼” Gauge Society John Nicholson, 14 Moorcroft, Eldwick, Nick Deytrikh, Allerton Wood, Stanhope, Co Durham, DL13 2JP ANNUAL SUBSCRIPTION - Bingley, West Yorkshire, BD16 3DR. -

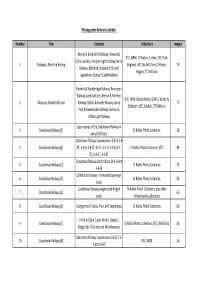

Photographic Reference Binders List

Photographic Reference Binders Number Title Contents Collections Images Aberford & Garforth Railway; Alexandra BTC; NRM; JF Bruton; Carrier; CCE York; Docks Railway; Ashover Light Railway; Barry 1 Railways: Aberford-Bishop England; LPC; Mullett; Nevitt; Pearce 79 Railway; Bideford, Westward Ho and Higgins; TE Williams Appledore; Bishop's Castle Railway Bodmin & Wadebridge Railway; Brampton Railway (Lord Carlisle); Brecon & Merthyr BTC; NRM; Derby Works; GWR; F Burtt; AJ 2 Railways: Bodmin-Burton Railway; Bristol & Exeter Railway; Burry 77 Chisholm; LPC; Mullett; TE Williams Port & Gwendraeth Railway: Burton & Ashby Light Railway Locomotives of the Caledonian Railway in 3 Caledonian Railway (1) St Rollox Photo Collection 36 early LMS livery Caledonian Railway Locomotives: 0-6-0; 0-6- 4 Caledonian Railway (2) 0T; 2-6-0; 0-8-0T; 4-2-2; 2-2-2; 2-4-0; 0-4- St Rollox Photo Collection; BTC 46 0T; 0-4-4T; 4-4-0T Caledonian Railway Locomotives (4-4-0 and 5 Caledonian Railway (3) St Rollox Photo Collection 75 4-6-0) Caledonian Railway - trains and passenger 6 Caledonian Railway (4) St Rollox Photo Collection 55 stock Caledonian Railway wagons and freight St Rollox Photo Collection; plus other 7 Caledonian Railway (5) 62 stock official works collections 8 Caledonian Railway (6) Grangemouth Docks, Piers and Steamships St Rollox Photo Collection 60 Forth & Clyde Canal; Works, Depots, 9 Caledonian Railway (7) St Rollox Photo Collection; BTC; NRM; Box 56 Bridges &c; Publicity and Miscellaneous Caledonian Railway Locomotives 0-6-0, 2-6- 10 Caledonian -

![[Front Cover Photograph]](https://docslib.b-cdn.net/cover/2555/front-cover-photograph-9562555.webp)

[Front Cover Photograph]

FIVE FOOT THREE No.59 March 2013 Editor: Edward Friel CONTENTS Editorial Chairman’s Report David Houston News From The Board Paul McCann Locomotive Report Peter Scott Dublin Carriage Report Niall Kelly Whitehead Carriage & Wagon Report Francis Richards Belfast Area Operations Mervyn Darragh Whitehead Site Report Dermot Mackie Development Report Denis Grimshaw Irish 0-6-4T Locomotives W.T. Scott Obituary: Brian Stinson John Friel Opinions expressed by contributors do not necessarily represent those of the Editor or the Board of the Society. All photographs are copyright either of the RPSI or of another photographer or collector, and may not be reproduced without permission. To contact Five Foot Three with letters, photographs or other contributions, send an email to [email protected], or write to: Five Foot Three P.O. Box 461 NEWTOWNABBEY County Antrim Northern Ireland BT36 9BT Front Cover: No. 186 shortly after leaving Athenry on 12th May 2012 with the “South Clare” railtour. (C.P. Friel) No.186 at Athenry on 12th May 2012 with the “South Clare” railtour. (C.P. Friel) EDITORIAL In producing Five Foot Three No.59 I thought it better that it should be complete than timely. Sadly it has turned out to be neither, coming as it does over halfway through the year and with less than the usual battery of reports. 2012 is already receding into the memory, and as you read some parts of this issue you may think that is the best place for it. Yet it had its moments. Despite everything, we have carried thousands of satisfied customers, a beautiful station building has sprung up at Whitehead and, at the start of 2013, we received new support both symbolic and material, with Charles Friel’s British Empire Medal and the Heritage Lottery Fund’s long-awaited big grant offer.