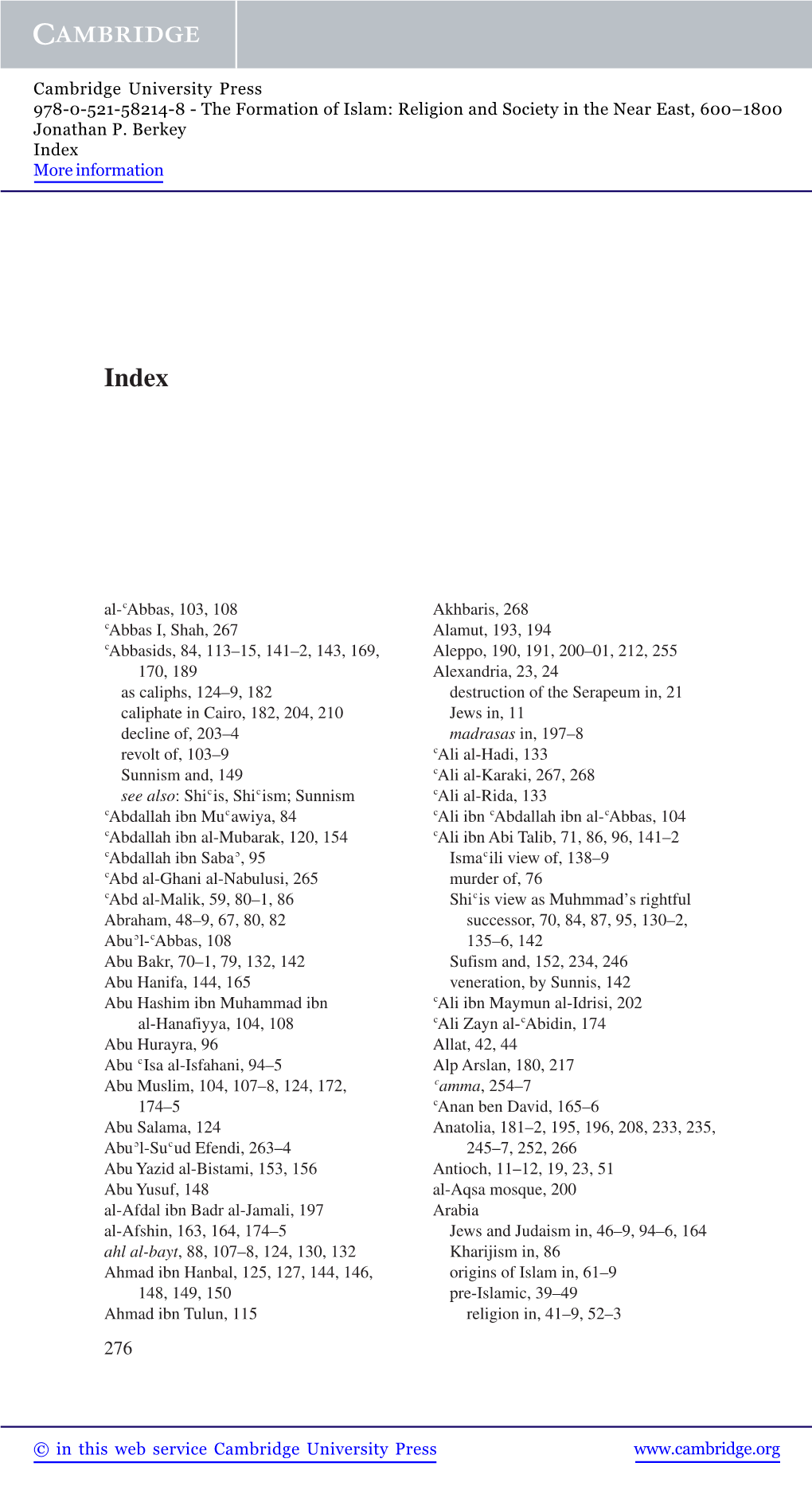

Al-Fiabbas, 103, 108 Fiabbas I, Shah, 267 Fiabbasids, 84, 113–15

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Spiritual Journey Author: Ali Hassnain Khan Khichi1 Reccive: 25/03/2019 Accept: 12/10/2019

Spiritual Journey Author: Ali Hassnain Khan Khichi1 Reccive: 25/03/2019 Accept: 12/10/2019 Problem Statement We will review in this spiritual journey One of the greatest personalities in sacrifice and redemption, he is Hussein bin Ali (Abu Shuhadaa) May Allah be pleased with him, My heart rejoiced and my pen because I have received that honor to write about an honorable person Son of the Master Ali ibn Abi Talib, a pure seed with deep roots in faith. Imam Hussein derives his glory from of the Messenger of Allah Muhammad Peace be upon him. In fact, I do not find much trouble in a flow of ideas which follows one idea after the other about the wonderful example in steadfastness on the right. And I am thirsty for the moment when the article will be finished to start reading it again. When I started in my writing, I did not know much about the subject, but when I read the references and resources and studied the details of Imam's life, I was surprised with many meanings that added a lot to my personality. When we talk about this great person we must mention the environment in which he grew up and the family from which he descended. They are a family of the Prophet Muhammad (Ahl Albeit), , who are distinguished by good deeds, redemption and sacrifice, the reason for their preference was their commitment to the method of God and they paid precious cost to become the word of God is the highest. َ ََّ ُ ْ َ ْ ُ ْ َ ْ َ ُ َ ْ )1( )إن َما ُيريد ُالله لُيذه َب عنك ُم َّالر ْج َس أهل ال َبْيت َو ُيط َّه َرك ْم تطه ًيرا( ِ ِ ِ ِ ِ ِ ِ ِ The Holy Prophet Muhammad has recommended all Muslims to love (Ahl Albeit) and keep them in mind. -

Information to Users

INFORMATION TO USERS This manuscript has been reproduced firom the microfilm master. UMT films the text directly fi’om the original or copy submitted. Thus, some thesis and dissertation copies are in typewriter 6ce, while others may be fi’om any type of computer printer. The quality of this reproduction is dependent upon the quality of the copy submitted. Broken or indistinct print, colored or poor quality illustrations and photographs, print bleedthrough, substandard margins, and improper alignment can adversely affect reproduction. In the unlikely event that the author did not send UMI a complete manuscript and there are missing pages, these will be noted. Also, if unauthorized copyright material had to be removed, a note will indicate the deletion. Oversize materials (e.g., maps, drawings, charts) are reproduced by sectioning the original, beginning at the upper left-hand comer and continuing fi’om left to right in equal sections with small overlaps. Each original is also photographed in one exposure and is included in reduced form at the back of the book. Photographs included in the original manuscript have been reproduced xerographically in this copy. Higher quality 6” x 9” black and white photographic prints are available for any photographs or illustrations appearing in this copy for an additional charge. Contact UMI directly to order. UMI A Bell & Ifowell Information Company 300 North Zeeb Road, Ann Arbor MI 48106-1346 USA 313/761-4700 800/521-0600 THE EMERGENCE AND DEVELOPMENT OF ARABIC RHETORICAL THEORY. 500 C £.-1400 CE. DISSERTATION Presented m Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of Doctor of Philosophy in the Graduate School of The Ohio State University By Khaiid Alhelwah, M.A. -

Índice De Nombres Propios A

Índice de nombres propios Los números en cursiva indican fotografías Abu.Muhammad (dai nizaríta), 195 Abu.Muslim. (Abdal.Arman.ibn.Muslim.al. A Jurassaní ), 51, 52, 53, 321, Abú.Raqwa, (Ibn.W alid.Hishames), 120, 121, Abass.I, el grande, safawiya., 219 331 Abd.Alá, padre de Mahoma, 317 Abu.Said.al.Hassan.ibn.Bahran.al.Jannabi Abd.Al.Baha, (bahai), 227, 230 (qármata), 86, Abd.Al.Kaim.Ha´iri, Sheik (ayatollah), 232 Abu.Soleiman.al.Busti, (ilwan al.saffa), 324 Abd.al.Malik.ibn.Attash, 161 Abu.Tahir.al.saigh (dai nizaríta sirio), 187, 188 Abd.Al.Mumin, (califa almohade), 49, 319 Abu.Tahir.ibn.Abú.Said (qármata), 86, 87 Abd.Al.Rahman, II, andalusí, 328 Abu.Tahir.al.Saigh —el orfebre“ (dai nizaríta), Abd.Al.Rahman III, califa de Al.Andalus, 321, 187, 188 328 Abú.Talib (padre de Alí), 31, 40, 43, Abdalláh, hermano de Nizar, 143, 144 Abu.Yacid, 101 Abdalláh.abu.Abass, califa abasida , 52, 64 Abud.al.Dawla, buyíes, 57 Abdalláh.al.Taashi, (califa ansarí), 342 Abul.Abbas.ibn.Abu.Muhammad, 92,93, 95, Abdalláh.al.Tanuji (drusos), 133 96 Abdalláh.ibn.Maimún (Imam fatimíta), 85 Abul.al.de.Bahlul, 89, 108 Abdalláh.Qatari (Mahdi), 264 Abul.Ala.al.Maari, 17 Abdan (qármata), 85, 86 Abul.Fazal.Raydam, 112 Abdel.Aziz.al.Rantisi, Hamas, 357 Abul.Hussein, dai ismailíta, 93 Abderrazac.Amari, Al.Qaida, 319 Abul.ibn.Abbas.Awan.Hanbali, 117 Abdul.Majid.II.(califa turco), 242 Abul.ibn.Hussein.al.Aswad (dai fatimíta), 91, Abdul.Malik.al.Ashrafani (drusos), 127 92 Abdul.Qafs, (qármata), 86 Abul.Kassim.ibn.Abú.Said (qármata), 86, 87, Abdul.Raman.ibn.Mulyam, jariyita, -

Proquest Dissertations

The history of the conquest of Egypt, being a partial translation of Ibn 'Abd al-Hakam's "Futuh Misr" and an analysis of this translation Item Type text; Dissertation-Reproduction (electronic) Authors Hilloowala, Yasmin, 1969- Publisher The University of Arizona. Rights Copyright © is held by the author. Digital access to this material is made possible by the University Libraries, University of Arizona. Further transmission, reproduction or presentation (such as public display or performance) of protected items is prohibited except with permission of the author. Download date 10/10/2021 21:08:06 Link to Item http://hdl.handle.net/10150/282810 INFORMATION TO USERS This manuscript has been reproduced from the microfilm master. UMI films the text directly fi-om the original or copy submitted. Thus, some thesis and dissertation copies are in typewriter face, while others may be from any type of computer printer. The quality of this reproduction is dependent upon the quality of the copy submitted. Broken or indistinct print, colored or poor quality illustrations and photographs, print bleedthrough, substandard margins, and improper alignment can adversely affect reproduction. In the unlikely event that the author did not send UMI a complete manuscript and there are missing pages, these will be noted. Also, if unauthorized copyright material had to be removed, a note will indicate the deletion. Oversize materials (e.g., maps, drawings, charts) are reproduced by sectiotiing the original, beginning at the upper left-hand comer and continuing from left to right in equal sections with small overlaps. Each original is also photographed in one exposure and is included in reduced form at the back of the book. -

The Camel-Section of the Panegyrical Ode Author(S): Renate Jacobi Source: Journal of Arabic Literature, Vol

The Camel-Section of the Panegyrical Ode Author(s): Renate Jacobi Source: Journal of Arabic Literature, Vol. 13 (1982), pp. 1-22 Published by: BRILL Stable URL: http://www.jstor.org/stable/4183059 . Accessed: 15/06/2014 23:43 Your use of the JSTOR archive indicates your acceptance of the Terms & Conditions of Use, available at . http://www.jstor.org/page/info/about/policies/terms.jsp . JSTOR is a not-for-profit service that helps scholars, researchers, and students discover, use, and build upon a wide range of content in a trusted digital archive. We use information technology and tools to increase productivity and facilitate new forms of scholarship. For more information about JSTOR, please contact [email protected]. BRILL is collaborating with JSTOR to digitize, preserve and extend access to Journal of Arabic Literature. http://www.jstor.org This content downloaded from 132.74.95.21 on Sun, 15 Jun 2014 23:43:38 PM All use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions Journal of Arabic Literature,XIII THE CAMEL-SECTION OF THE PANEGYRICAL ODE' When comparing Arabic odes from different periods, the reader is sure to notice a certain discrepancy with regard to the main parts of the qasida: erotic prologue (nasib), camel-theme (wasf al-jamal and/or rahil), panegyric (madih). I mean the fact that the first and last section remain almost unchanged as structural units of the ode, whereas the second part, the camel-theme, changes radically from Pre-Islamic to Abbasid times. That is to say, although nasTband madzhpresent many aspects of internal change and development, and even more so, I believe, than has been recognized up to now, they continue to form substantial elements of the genre. -

Fatwâ : Its Role in Sharî'ah and Contemporary Society with South

Fatwen Its Role in Shari 'di and Contemporary Society with South African Case Studies BY NASIM MITHA DISSERTATION Submitted in fulfilment of the requirements for the degree MASTER OF ARTS in ISLAMIC STUDIES in the FACULTY OF ARTS at the RAND AFRIKAANS UNIVERSITY SUPERVISOR: PROF. A.R.I. DOI CO - SUPERVISOR: PROF. J.F.J.VAN RENSBURG MAY 1999 Acknowledgement Praise be to Allah who in his infinite mercy has endowed me with the ability to undertake and complete this work on fanvci, a topic which has hitherto been neglected. Confusion regarding the concepts of fatwci, agOya, mufti, qcich and exikim abounds in the South African Muslim community. In consequence the entire Shatfah is misunderstood and misrepresented. It is my fervent hope that this study redresses this problem to some extent and induces others to produce further work on this topic. The Prophet (may peace be upon him) has reported to have said, "He who does not thank man has not thanked Allah." It is with these words of our master in mind that I acknowledge the efforts of all those who made this task possible. Firstly, I deeply appreciate the effort made by my teachers, and principal Moulana Cassim Seema of Dar al-Vitim Newcastle, who had guided me in my quest for Islamic knowledge and also to my sheikh of tasawwuf Moulana Ibrahim Mia for being my spiritual mentor. I thank my supervisor Professor `Abd al-Ralunan Doi at whose insistence this particular topic was chosen, and for the innumerable advice, guidance, and support afforded whilst the research was being undertaken. -

Khadija Daughtr of Khuwaylid

KHADIJA DAUGHTR OF KHUWAYLID In the year 595, Muhammed son of Abdullah, Prophet of Islam, was old enough to go with trade caravans in the company of other kinsmen from the populous Quraish tribe. But the financial position of his uncle, Abu Talib, who raised him after the death of his father, had become very weak because of the expenses of rifada and siqaya , the housing and feeding of pilgrims of the holy “House of God” which Abraham and Ishmael had rebuilt following damage caused by torrential rain. It was no longer possible for Abu Talib to equip his nephew, Muhammed, with merchandise on his own. He, therefore, advised him to act as agent for a noble lady, Khadija bint (daughter of) Khuwaylid, who was the wealthiest person in Quraish. Her genealogy joins with that of the Prophet at Qusayy. She was Khadija daughter of Khuwaylid ibn Asad ibn `Abdul-`Ozza ibn Qusayy. She, hence, was a distant cousin of Muhammed. The reputation which Muhammed enjoyed for his honesty and integrity led Khadija to willingly entrust her mercantile goods to him for sale in Syria. She sent him word through his friend Khazimah ibn Hakim, a relative of hers, offering him twice the commission she used to pay her agents to trade on her behalf. Muhammed, with the consent of his uncle Abu Talib, accepted her offer. Most references consulted for this essay make a casual mention of Khadija. This probably reflects a male chauvinistic attitude which does a great deal of injustice to this great lady, the mother of the faithful whose wealth contributed so much to the dissemination of Islam. -

Al-Hadl Yahya B. Ai-Husayn: an Introduction, Newly Edited Text and Translation with Detailed Annotation

Durham E-Theses Ghayat al-amani and the life and times of al-Hadi Yahya b. al-Husayn: an introduction, newly edited text and translation with detailed annotation Eagle, A.B.D.R. How to cite: Eagle, A.B.D.R. (1990) Ghayat al-amani and the life and times of al-Hadi Yahya b. al-Husayn: an introduction, newly edited text and translation with detailed annotation, Durham theses, Durham University. Available at Durham E-Theses Online: http://etheses.dur.ac.uk/6185/ Use policy The full-text may be used and/or reproduced, and given to third parties in any format or medium, without prior permission or charge, for personal research or study, educational, or not-for-prot purposes provided that: • a full bibliographic reference is made to the original source • a link is made to the metadata record in Durham E-Theses • the full-text is not changed in any way The full-text must not be sold in any format or medium without the formal permission of the copyright holders. Please consult the full Durham E-Theses policy for further details. Academic Support Oce, Durham University, University Oce, Old Elvet, Durham DH1 3HP e-mail: [email protected] Tel: +44 0191 334 6107 http://etheses.dur.ac.uk 2 ABSTRACT Eagle, A.B.D.R. M.Litt., University of Durham. 1990. " Ghayat al-amahr and the life and times of al-Hadf Yahya b. al-Husayn: an introduction, newly edited text and translation with detailed annotation. " The thesis is anchored upon a text extracted from an important 11th / 17th century Yemeni historical work. -

TOMBS and FOOTPRINTS: ISLAMIC SHRINES and PILGRIMAGES IN^IRAN and AFGHANISTAN Wvo't)&^F4

TOMBS AND FOOTPRINTS: ISLAMIC SHRINES AND PILGRIMAGES IN^IRAN AND AFGHANISTAN WvO'T)&^f4 Hugh Beattie Thesis presented for the degree of M. Phil at the University of London School of Oriental and African Studies 1983 ProQuest Number: 10672952 All rights reserved INFORMATION TO ALL USERS The quality of this reproduction is dependent upon the quality of the copy submitted. In the unlikely event that the author did not send a com plete manuscript and there are missing pages, these will be noted. Also, if material had to be removed, a note will indicate the deletion. uest ProQuest 10672952 Published by ProQuest LLC(2017). Copyright of the Dissertation is held by the Author. All rights reserved. This work is protected against unauthorized copying under Title 17, United States C ode Microform Edition © ProQuest LLC. ProQuest LLC. 789 East Eisenhower Parkway P.O. Box 1346 Ann Arbor, Ml 48106- 1346 abstract:- The thesis examines the characteristic features of Islamic shrines and pilgrimages in Iran and Afghan istan, in doing so illustrating one aspect of the immense diversity of belief and practice to be found in the Islamic world. The origins of the shrine cults are outlined, the similarities between traditional Muslim and Christian attitudes to shrines are emphasized and the functions of the shrine and the mosque are contrasted. Iranian and Afghan shrines are classified, firstly in terms of the objects which form their principal attrac tions and the saints associated with them, and secondly in terms of the distances over which they attract pilgrims. The administration and endowments of shrines are described and the relationship between shrines and secular authorities analysed. -

The Institute of Ismaili Studies

The Institute of Ismaili Studies “Ismailis” Medieval Islamic Civilization: An Encyclopedia Farhad Daftary Early Ismaili History In 148 AH/765 CE, on the death of Imam Ja‘far al-Sadiq, who had consolidated Imami Shi‘ism, the majority of his followers recognised his son Musa al-Kazim as their new imam. However, other Imami Shi‘i groups acknowledged the imamate of Musa’s older half-brother, Isma‘il, the eponym of the Ismalliyya, or Isma‘il’s son Muhammad. Little is known about the life and career of Muhammad ibn Isma‘il, who went into hiding, marking the initiation of the dawr al-satr, or period of concealment, in early Ismaili history which lasted until the foundation of the Fatimid state when the Ismaili imams emerged openly as Fatimid caliphs. On the death of Muhammad ibn Isma‘il, not long after 179 AH/795 CE, his followers, who were at the time evidently known as Mubarakiyya, split into two groups. A majority refused to accept his death; they recognised him as their seventh and last imam and awaited his return as the Mahdi, the restorer of justice and true Islam. A second, smaller group acknowledged Muhammad’s death and traced the imamate in his progeny. Almost nothing is known about the subsequent history of these earliest Ismaili groups until shortly after the middle of the third AH/ninth century CE. It is certain that for almost a century after Muhammad ibn Ismail, a group of his descendants worked secretly for the creation of a revolutionary movement, the aim of which was to install the Ismaili imam belonging to the Prophet Muhammad’s family (ahl al-bayt) to a new caliphate ruling over the entire Muslim community; and the message of the movement was disseminated by a network of da‘is (summoners). -

In Kitab Al-Aghani

Turkish Journal of Computer and Mathematics Education Vol.12 No 13 (2021), 5053-5059 Research Article The Description of Ahl al-Bayt (PBUT) in Kitab al-Aghani Ayatollah Zarmohammadi a a Department of History of Civilization of Islamic Nations, University of Zanjan, Zanjan, Iran. Article History: Received: 5 April 2021; Accepted: 14 May 2021; Published online: 22 June 2021 Abstract: In Islamic sources, whether interpretive, narrative or historical, the Ahl al-Bayt (PBUT) are mostly referred to with high reverence, and graceful trait are attributed thereto. yet, their commemoration in one of the most glorious works of early Arabic literature, namely Kitab al-Aghani, is of paramount significance. Attributed to the 10th-century Arabic writer Abu al- Faraj al-Isfahani (also known as al-Isbahani), it is claimed to have taken 50 years to write the work. Considering that he is a descendant of the Marwanis, mentioning the virtues of the Ahl al-Bayt (PBUT) in this book further highlights their legitimacy, making everyone awe in praise. Further, the claims cited in the work have been mostly backed by referring to other Sunni and possibly Shiite sources. With a descriptive-analytical approach, the purpose of this study was to introduce the Ahl al-Bayt (PBUT) in the Kitab al-Aghani, while pointing out issues such as the succession of Ali (PBUH), the succession of Imam Hassan (PBUH) and Messianism of Mahdi (PBUH). Keywords: Ahl al-Bayt (PBUT), Abu al-Faraj al-Isfahani, Kitab al-Aghani 1. Introduction In the present age where spirituality is marginalized, the rational and spiritualistic people are on the quest for true rationality and spirituality, and seek to achieve the transcendent goal of creation, i.e., salvation, by heartfully following the prophets and their true successors to guide them with the illuminating light from darkness to light. -

Kocaer 3991.Pdf

Kocaer, Sibel (2015) The journey of an Ottoman arrior dervish : The Hı ırname (Book of Khidr) sources and reception. PhD Thesis. SOAS, University of London. http://eprints.soas.ac.uk/id/eprint/20392 Copyright © and Moral Rights for this PhD Thesis are retained by the author and/or other copyright owners. A copy can be downloaded for personal non‐commercial research or study, without prior permission or charge. This PhD Thesis cannot be reproduced or quoted extensively from without first obtaining permission in writing from the copyright holder/s. The content must not be changed in any way or sold commercially in any format or medium without the formal permission of the copyright holders. When referring to this PhD Thesis, full bibliographic details including the author, title, awarding institution and date of the PhD Thesis must be given e.g. AUTHOR (year of submission) "Full PhD Thesis title", name of the School or Department, PhD PhD Thesis, pagination. The Journey of an Ottoman Warrior Dervish: The Hızırname (Book of Khidr) Sources and Reception SIBEL KOCAER Thesis submitted for the degree of PhD 2015 Department of the Languages and Cultures of the Near and Middle East SOAS, University of London Declaration for SOAS PhD thesis I have read and understood regulation 17.9 of the Regulations for students of the SOAS, University of London concerning plagiarism. I undertake that all the material presented for examination is my own work and has not been written for me, in whole or in part, by any other person. I also undertake that any quotation or paraphrase from the published or unpublished work of another person has been duly acknowledged in the work which I present for examination.