Changing Concepts of Heat in the Early Nineteenth Century ROBERT JAMES MORRIS, JR., University of Oklahoma, Norma

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Chapter Two: the Astronomers and Extraterrestrials

Warning Concerning Copyright Restrictions The Copyright Law of the United States (Title 17, United States Code) governs the making of photocopies or other reproductions of copyrighted materials, Under certain conditions specified in the law, libraries and archives are authorized to furnish a photocopy or other reproduction, One of these specified conditions is that the photocopy or reproduction is not to be used for any purpose other than private study, scholarship, or research , If electronic transmission of reserve material is used for purposes in excess of what constitutes "fair use," that user may be liable for copyright infringement. • THE EXTRATERRESTRIAL LIFE DEBATE 1750-1900 The idea of a plurality of worlds from Kant to Lowell J MICHAEL]. CROWE University of Notre Dame TII~ right 0/ ,It, U,,;v"Jily 0/ Camb,idg4' to P'''''' a"d s,1I all MO""" of oooks WM grattlrd by H,rr,y Vlf(;ff I $J4. TM U,wNn;fyltas pritr"d and pu"fisllrd rOffti",.ously sincr J5U. Cambridge University Press Cambridge London New York New Rochelle Melbourne Sydney Published by the Press Syndicate of the University of Cambridge In lovi ng The Pirr Building, Trumpingron Srreer, Cambridge CB2. I RP Claire H 32. Easr 57th Streer, New York, NY 1002.2., U SA J 0 Sramford Road, Oakleigh, Melbourne 3166, Australia and Mi ha © Cambridge Univ ersiry Press 1986 firsr published 1986 Prinred in rh e Unired Srares of America Library of Congress Cataloging in Publication Data Crowe, Michael J. The exrrarerresrriallife debare '750-1900. Bibliography: p. Includes index. I. Pluraliry of worlds - Hisrory. -

Thinking Outside the Sphere Views of the Stars from Aristotle to Herschel Thinking Outside the Sphere

Thinking Outside the Sphere Views of the Stars from Aristotle to Herschel Thinking Outside the Sphere A Constellation of Rare Books from the History of Science Collection The exhibition was made possible by generous support from Mr. & Mrs. James B. Hebenstreit and Mrs. Lathrop M. Gates. CATALOG OF THE EXHIBITION Linda Hall Library Linda Hall Library of Science, Engineering and Technology Cynthia J. Rogers, Curator 5109 Cherry Street Kansas City MO 64110 1 Thinking Outside the Sphere is held in copyright by the Linda Hall Library, 2010, and any reproduction of text or images requires permission. The Linda Hall Library is an independently funded library devoted to science, engineering and technology which is used extensively by The exhibition opened at the Linda Hall Library April 22 and closed companies, academic institutions and individuals throughout the world. September 18, 2010. The Library was established by the wills of Herbert and Linda Hall and opened in 1946. It is located on a 14 acre arboretum in Kansas City, Missouri, the site of the former home of Herbert and Linda Hall. Sources of images on preliminary pages: Page 1, cover left: Peter Apian. Cosmographia, 1550. We invite you to visit the Library or our website at www.lindahlll.org. Page 1, right: Camille Flammarion. L'atmosphère météorologie populaire, 1888. Page 3, Table of contents: Leonhard Euler. Theoria motuum planetarum et cometarum, 1744. 2 Table of Contents Introduction Section1 The Ancient Universe Section2 The Enduring Earth-Centered System Section3 The Sun Takes -

The History of Optical Astronomy, by Caroline Herschel and Lyman Spitzer

Online Modules from The University of Chicago Multiwavelength Astronomy: The History of Optical Astronomy, by Caroline Herschel and Lyman Spitzer http://ecuip.lib.uchicago.edu/multiwavelength-astronomy/optical/history/index.html Subject(s): Astronomy/Space Science Grade(s) Level: 9-12 Duration: One Class Period Objectives: As a result of reading The History of Optical Astronomy, students will be able to • Discriminate between reflecting and refracting telescope designs and describe the differences between them; • Explain how a telescope focuses light; • Articulate the limitations of ground-based telescopes and propose solutions to these limitations; • Identify important astronomical discoveries made and personages working in the optical regime; • Discuss examples of problem-solving and creativity in astronomy. Materials: Internet connection and browser for displaying the lesson. Pre-requisites: Students should be familiar with the Electromagnetic Spectrum. Before using the lesson, students should familiarize themselves with all vocabulary terms. Procedures: Students will read the lesson and answer assessment questions (listed under evaluation). Introduction: In reading this lesson, you will meet important individuals in the History of Optical Astronomy. They are: Caroline Lucretia Herschel was a German-born British astronomer and the sister of astronomer Sir William Herschel. She is the discoverer of several comets, in particular, the periodic comet 35P/Herschel-Rigollet, which bears her name. Lyman Strong Spitzer, Jr. was an American theoretical physicist, astronomer and mountaineer. He carried out research into star formation, plasma physics, and in 1946, conceived the idea of telescopes operating in outer space. Spitzer is the namesake of NASA's Spitzer Space Telescope. 1 Online Modules from The University of Chicago William Herschel was an astronomer and composer. -

Sensing the Invisible: the Herschel Experiment

MESS E N G E R S ENSIN G THE I NVISIB L E Y R HE ERSCHEL XPERIMENT U T H E C R E M TO N M I S S I O L E S S O N O V E RV I E W GRADE LEVEL 5 - 8 L ESSON S UMMARY In this lesson, students find out that there is radiation other than visible light arriving from the Sun. The students reproduce a version of William DURATION 1-2 hours Herschel’s experiment of 800 that discovered the existence of infrared radiation. The process of conducting the experiment and placing it in the historical context illustrates how scientific discoveries are often made ESSENTIAL QUESTION via creative thinking, careful design of the experiment, and adaptation of Are there forms of light other than visible light the experiment to accommodate unexpected results. Students discuss emitted by the Sun? current uses of infrared radiation and learn that it is both very beneficial and a major concern for planetary explorations such as the MESSENGER mission to Mercury. Lesson 1 of Grades 5-8 Component of Staying Cool O BJECTIVES Students will be able to: ▼ Construct a device to measure the presence of infrared radiation in sunlight. ▼ Explain that visible light is only part of the electromagnetic spectrum of radiation emitted by the Sun. ▼ Follow the path taken by Herschel through scientific discovery. ▼ Explain why we would want to use infrared radiation to study Mercury and other planets. ▼ Explain how excess infrared radiation is a concern for the MESSENGER mission. -

The Herschels and Their Astronomy

The Herschels and their Astronomy Mary Kay Hemenway 24 March 2005 outline • William Herschel • Herschel telescopes • Caroline Herschel • Considerations of the Milky Way • William Herschel’s discoveries • John Herschel Wm. Herschel (1738-1822) • Born Friedrich Wilhelm Herschel in Hanover, Germany • A bandboy with the Hanoverian Guards, later served in the military; his father helped him to leave Germany for England in 1757 • Musician in Bath • He read Smith's Harmonies, and followed by reading Smith's Optics - it changed his life. Miniature portrait from 1764 Discovery of Uranus 1781 • William Herschel used a seven-foot Newtonian telescope • "in the quartile near zeta Tauri the lowest of the two is a curious either Nebulous Star or perhaps a Comet” • He called it “Georgium Sidus" after his new patron, George Ill. • Pension of 200 pounds a year and knighted, the "King's Astronomer” -- now astronomy full time. Sir William Herschel • Those who had received a classical education in astronomy agreed that their job was to study the sun, moon, planets, comets, individual stars. • Herschel acted like a naturalist, collecting specimens in great numbers, counting and classifying them, and later trying to organize some into life cycles. • Before his discovery of Uranus, Fellows of the Royal Society had contempt for his ignorance of basic procedures and conventions. Isaac Newton's reflecting telescope 1671 William Herschel's 20-foot, 1783 Account of some Observations tending to investigate the Construction of the Heavens Philosophical Transactions of the Royal Society of London (1784) vol. 74, pp. 437-451 In a former paper I mentioned, that a more powerful instrument was preparing for continuing my reviews of the heavens. -

The Astronomy of Sir John Herschel

Introduction m m m m m m m m m m m Herschel’s Stars The Stars flourish, and in spite of all my attempts to thin them and . stuff them in my pockets, continue to afford a rich harvest. John Herschel to James Calder Stewart, July 17, 1834 n 2017, TRAPPIST-1, a red dwarf star forty light years from Earth, made headlines as the center of a system with not one or two but Iseven potentially habitable exoplanets.1 This dim, nearby star offers only the most recent example of verification of the sort of planetary system common in science fiction: multiple temperate, terrestrial worlds within a single star’s family of planets. Indeed, this discovery followed the an- nouncement only a few years earlier of the very first Earth-sized world orbiting within the habitable zone of its star, Kepler-186, five hundred light years from Earth.2 Along with other ongoing surveys and advanced instruments, the Kepler mission, which recently added an additional 715 worlds to a total of over five thousand exoplanet candidates, is re- vealing a universe in which exoplanets proliferate, Earth-like worlds are common, and planets within the habitable zone of their host star are far from rare.3 Exoplanetary astronomy has developed to the point that as- tronomers can not only detect these objects but also describe the phys- ical characteristics of many with a high degree of confidence and pre- cision, gaining information on their composition, atmospheric makeup, temperature, and even weather patterns. 3 © 2018 University of Pittsburgh Press. All rights reserved. -

Torrens, Hugh

BSHS Monographs publishes work of lasting scholarly value that might not otherwise be made available, and aids the dissemination of innovative projects advancing scholarship or education in the field. 13. Chang, Hasok and Jackson, 06. Morris, PJT, and Russell, CA; Catherine (eds.). 2007. An Smith, JG (ed.). 1988. Archives of Element of Controversy: The Life the British Chemical Industry, of Chlorine in Science, Medicine, 1750‐1914: A Handlist. Technology and War. ISBN 0‐0906450‐06‐3. ISBN: 978‐0‐906450‐01‐7. 05. Rees, Graham. 1984. Francis 12. Thackray, John C. (ed.). 2003. Bacon's Natural Philosophy: A To See the Fellows Fight: Eye New Source. Witness Accounts of Meetings of ISBN 0‐906450‐04‐7. the Geological Society of London 04. Hunter, Michael. 1994. The and Its Club, 1822‐1868. 2003. Royal Society and Its Fellows, ISBN: 0‐906450‐14‐4. 1660‐1700. 2nd edition. 11. Field, JV and James, Frank ISBN 978‐0‐906450‐09‐3. AJL. 1997. Science in Art. 03. Wynne, Brian. 1982. ISBN 0‐906450‐13‐6. Rationality and Ritual: The 10. Lester, Joe and Bowler, Windscale Inquiry and Nuclear Peter. E. Ray Lankester and the Decisions in Britain. Making of Modern British ISBN 0‐906450‐02‐0 Biology. 1995. 02. Outram, Dorinda (ed.). 2009. ISBN 978‐0‐906450‐11‐6. The Letters of Georges Cuvier. 09. Crosland, Maurice. 1994. In reprint of 1980 edition. the Shadow of Lavoisier: ISBN 0‐906450‐05‐5. ISBN 0‐906450‐10‐1. 01. Jordanova, L. and Porter, Roy 08. Shortland, Michael (ed.). (eds.). 1997. Images of the Earth: 1993. -

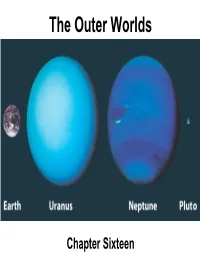

The Outer Worlds

The Outer Worlds Chapter Sixteen ASTR 111 – 003 Fall 2006 Lecture 13 Nov. 27, 2006 Introduction To Modern Astronomy I Ch7: Comparative Planetology I Introducing Astronomy Ch8: Comparative Planetology II (chap. 1-6) Ch9: The Living Earth Ch10: Our Barren Moon Ch11: Sun-Scorched Mercury Ch12: Cloud-covered Venus Planets and Moons Ch13: Red Planet Mars (chap. 7-17) Ch14: Jupiter and Saturn Ch15: Satellites of Jup. & Saturn Ch16: Outer World Ch17: Vagabonds of Solar System Update to Textbook • International Astronomical Union (IAU) voted on the re- definition of planets in Prague on Aug. 24, 2006. • Pluto is no longer a planet – Pluto is now called “dwarf planet” • Ceres, the largest asteroid, is also now classified as “dwarf planet” • 2003 UB, once proposed as 10th planet, is also a “dward planet” Guiding Questions 1. How did Uranus and Neptune come to be discovered? 2. What gives Uranus its distinctive greenish-blue color? 3. Why are the clouds on Neptune so much more visible than those on Uranus? 4. Are Uranus and Neptune merely smaller versions of Jupiter and Saturn? 5. What is so unusual about the magnetic fields of Uranus and Neptune? 6. Why are the rings of Uranus and Neptune so difficult to see? 7. Do the moons of Uranus show any signs of geologic activity? 8. What makes Neptune’s moon Triton unique in the solar system? 9. Are there other planets beyond Pluto? Uranus Data Neptune Data Pluto Data Discovery • Other than those planets seen by naked eyes, Uranus and Neptune were discovered by telescopes • Uranus was recognized as a planet -

Teacher Exhibition Notes Moving to Mars

TEACHER EXHIBITION NOTES MOVING TO MARS 18 OCTOBER 2019 - 23 FEBRUARY 2020 TEACHER NOTES These teacher notes are extracted from the exhibition text. The introduction, section headers and captions are as found in Moving to Mars. The exhibition is split into six sections within which sub sections focus on key groups of objects such as ‘Pressure suits and spacesuits’ and ‘Eating in Space’. These sections are represented in these notes but the expanded text can be found in the exhibition. A few exhibits from each category have been selected to enable you to guide your students’ journey around the exhibition and point of some exhibits of interest as you go. If you would like a more in-depth look around the exhibition, then you may be a free preliminary visit once you have made your group booking. We do not run tours of our galleries but our visitor experience assistants who are based in the galleries are knowledgeable on much of the content. Photography and cinematography is permitted in the gallery without the use of a flash. Dry sketching is allowed. No food or drink is allowed in the gallery. Please do not touch any objects unless instructed to do so in gallery signage. 1. IMAGANING MARS Mars is the most striking planet in the night sky. Its reddish glow and wandering motion fascinated ancient astronomers. Mars promised fire, destruction and war. From early maps to Hollywood film posters, the ways we have represented the Red Planet reflect our shifting understanding of it. As telescopes developed, astronomers could read Mars more deeply. -

Joanna Baillie and Sir John Herschel Judith Bailey Slagle East Tennessee State University, [email protected]

East Tennessee State University Digital Commons @ East Tennessee State University ETSU Faculty Works Faculty Works Spring 1-1-2018 Joanna Baillie and Sir John Herschel Judith Bailey Slagle East Tennessee State University, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://dc.etsu.edu/etsu-works Part of the English Language and Literature Commons Citation Information Slagle, Judith Bailey. 2018. Joanna Baillie and Sir John Herschel. The Wordsworth Circle. Vol.49(2). 85-92. This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Faculty Works at Digital Commons @ East Tennessee State University. It has been accepted for inclusion in ETSU Faculty Works by an authorized administrator of Digital Commons @ East Tennessee State University. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Joanna Baillie and Sir John Herschel Copyright Statement Authors are entitled to use their work any way they see fit os long as they acknowledge its appearance in TWC. This document was originally published in The Wordsworth Circle. This article is available at Digital Commons @ East Tennessee State University: https://dc.etsu.edu/etsu-works/3212 Joanna Baillie and SirJohn Herschel Judith Bailey Slagle East Tennessee State University Joanna Baillie(l 762-1851), the Scottish poet themselves or the community. I knew and dramatist, was raised in a family of scientists: Malthus, he used to come frequently to Hamp her uncles, the renowned physicians and anatomists, stead to visit a Sister, and a most humane and un William and John Hunter, and her brother, Mat assuming good man he was" (Slagle 975-75). thew. -

Historical & Cultural Astronomy

Historical & Cultural Astronomy Historical & Cultural Astronomy EDITORIAL BOARD JAMES EVANS, University of Puget Sound, USA MILLER GOSS, National Radio Astronomy Observatory, USA JAMES LEQUEUX, Observatoire de Paris, France SIMON MITTON, St. Edmund’s College Cambridge University, UK WAYNE ORCHISTON, National Astronomical Research Institute of Thailand, Thailand MARC ROTHENBERG, AAS Historical Astronomy Division Chair, USA VIRGINIA TRIMBLE, University of California Irvine, USA XIAOCHUN SUN, Institute of History of Natural Science, China GUDRUN WOLFSCHMIDT, Institute for History of Science and Technology, Germany More information about this series at http://www.springer.com/series/15156 Clifford J. Cunningham Editor The Scientific Legacy of William Herschel Editor Clifford J. Cunningham Austin, Texas, USA ISSN 2509-310X ISSN 2509-3118 (electronic) Historical & Cultural Astronomy ISBN 978-3-319-32825-6 ISBN 978-3-319-32826-3 (eBook) https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-319-32826-3 Library of Congress Control Number: 2017952742 © Springer International Publishing Switzerland 2018 This work is subject to copyright. All rights are reserved by the Publisher, whether the whole or part of the material is concerned, specifically the rights of translation, reprinting, reuse of illustrations, recitation, broadcasting, reproduction on microfilms or in any other physical way, and transmission or information storage and retrieval, electronic adaptation, computer software, or by similar or dissimilar methodology now known or hereafter developed. The use of general descriptive names, registered names, trademarks, service marks, etc. in this publication does not imply, even in the absence of a specific statement, that such names are exempt from the relevant protective laws and regulations and therefore free for general use. -

Ms. Coll. 251: Literary Models, Religion, and Romantic Science in John Syng Dorsey’S Poems, 1805-1818 Samantha Destefano

University of Pennsylvania ScholarlyCommons Transcription Collection Penn Manuscript Collective 5-2019 Ms. Coll. 251: Literary Models, Religion, and Romantic Science in John Syng Dorsey’s Poems, 1805-1818 Samantha DeStefano Follow this and additional works at: https://repository.upenn.edu/ manuscript_collective_transcription Part of the American Literature Commons, American Material Culture Commons, Archival Science Commons, Digital Humanities Commons, English Language and Literature Commons, Health Sciences and Medical Librarianship Commons, History of Science, Technology, and Medicine Commons, and the United States History Commons Recommended Citation DeStefano, Samantha, "Ms. Coll. 251: Literary Models, Religion, and Romantic Science in John Syng Dorsey’s Poems, 1805-1818" (2019). Transcription Collection. 6. https://repository.upenn.edu/manuscript_collective_transcription/6 This paper is posted at ScholarlyCommons. https://repository.upenn.edu/manuscript_collective_transcription/6 For more information, please contact [email protected]. Ms. Coll. 251: Literary Models, Religion, and Romantic Science in John Syng Dorsey’s Poems, 1805-1818 Description John Syng Dorsey (1783-1818) was a Philadelphia surgeon and the author of The Elements of Surgery (1813), the first American textbook of surgery. He was also the author of Poems, 1805-1818 (UPenn Ms. Coll. 251), a forty-page collection that reveals his interests in spirituality, the history of science and medicine, and classical and eighteenth-century British poetry. Decades after Dorsey’s death, his son Robert Ralston Dorsey (1808-1869) revised his father’s poems, identified classical sources with Latin and Italian quotations, and completed Dorsey’s final, unfinished poem. This project analyzes Dorsey’s literary, scientific, nda biblical allusions and contextualizes his Poems within early nineteenth-century literary history and Romantic science and medicine.