Tityus: a Forgotten Myth of Liver Regeneration

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Odyssey Glossary of Names

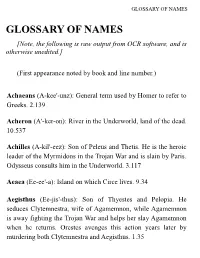

GLOSSARY OF NAMES GLOSSARY OF NAMES [Note, the following is raw output from OCR software, and is otherwise unedited.] (First appearance noted by book and line number.) Achaeans (A-kee'-unz): General term used by Homer to reFer to Greeks. 2.139 Acheron (A'-ker-on): River in the Underworld, land of the dead. 10.537 Achilles (A-kil'-eez): Son of Peleus and Thetis. He is the heroic leader of the Myrmidons in the Trojan War and is slain by Paris. Odysseus consults him in the Underworld. 3.117 Aeaea (Ee-ee'-a): Island on which Circe lives. 9.34 Aegisthus (Ee-jis'-thus): Son of Thyestes and Pelopia. He seduces Clytemnestra, wife of Agamemnon, while Agamemnon is away fighting the Trojan War and helps her slay Agamemnon when he returns. Orestes avenges this action years later by murdering both Clytemnestra and Aegisthus. 1.35 GLOSSARY OF NAMES Aegyptus (Ee-jip'-tus): The Nile River. 4.511 Aeolus (Ee'-oh-lus): King of the island Aeolia and keeper of the winds. 10.2 Aeson (Ee'-son): Son oF Cretheus and Tyro; father of Jason, leader oF the Argonauts. 11.262 Aethon (Ee'-thon): One oF Odysseus' aliases used in his conversation with Penelope. 19.199 Agamemnon (A-ga-mem'-non): Son oF Atreus and Aerope; brother of Menelaus; husband oF Clytemnestra. He commands the Greek Forces in the Trojan War. He is killed by his wiFe and her lover when he returns home; his son, Orestes, avenges this murder. 1.36 Agelaus (A-je-lay'-us): One oF Penelope's suitors; son oF Damastor; killed by Odysseus. -

HOMERIC-ILIAD.Pdf

Homeric Iliad Translated by Samuel Butler Revised by Soo-Young Kim, Kelly McCray, Gregory Nagy, and Timothy Power Contents Rhapsody 1 Rhapsody 2 Rhapsody 3 Rhapsody 4 Rhapsody 5 Rhapsody 6 Rhapsody 7 Rhapsody 8 Rhapsody 9 Rhapsody 10 Rhapsody 11 Rhapsody 12 Rhapsody 13 Rhapsody 14 Rhapsody 15 Rhapsody 16 Rhapsody 17 Rhapsody 18 Rhapsody 19 Rhapsody 20 Rhapsody 21 Rhapsody 22 Rhapsody 23 Rhapsody 24 Homeric Iliad Rhapsody 1 Translated by Samuel Butler Revised by Soo-Young Kim, Kelly McCray, Gregory Nagy, and Timothy Power [1] Anger [mēnis], goddess, sing it, of Achilles, son of Peleus— 2 disastrous [oulomenē] anger that made countless pains [algea] for the Achaeans, 3 and many steadfast lives [psūkhai] it drove down to Hādēs, 4 heroes’ lives, but their bodies it made prizes for dogs [5] and for all birds, and the Will of Zeus was reaching its fulfillment [telos]— 6 sing starting from the point where the two—I now see it—first had a falling out, engaging in strife [eris], 7 I mean, [Agamemnon] the son of Atreus, lord of men, and radiant Achilles. 8 So, which one of the gods was it who impelled the two to fight with each other in strife [eris]? 9 It was [Apollo] the son of Leto and of Zeus. For he [= Apollo], infuriated at the king [= Agamemnon], [10] caused an evil disease to arise throughout the mass of warriors, and the people were getting destroyed, because the son of Atreus had dishonored Khrysēs his priest. Now Khrysēs had come to the ships of the Achaeans to free his daughter, and had brought with him a great ransom [apoina]: moreover he bore in his hand the scepter of Apollo wreathed with a suppliant’s wreath [15] and he besought the Achaeans, but most of all the two sons of Atreus, who were their chiefs. -

A Synopsis of the Amber Scorpions, with Special Reference to the Baltic Fauna 131-136 © Biologiezentrum Linz/Austria; Download Unter

ZOBODAT - www.zobodat.at Zoologisch-Botanische Datenbank/Zoological-Botanical Database Digitale Literatur/Digital Literature Zeitschrift/Journal: Denisia Jahr/Year: 2009 Band/Volume: 0026 Autor(en)/Author(s): Lourenco Wilson R. Artikel/Article: A synopsis of the amber scorpions, with special reference to the Baltic fauna 131-136 © Biologiezentrum Linz/Austria; download unter www.biologiezentrum.at A synopsis of the amber scorpions, with special reference to the Baltic fauna W ilson R. L OURENÇO Abstract: A synopsis of the fossil scorpions found in amber, from the Lower Cretaceous to the Miocene, is presented. Scorpion remains are rare among the arthropods found trapped in amber. Only five specimens are known from Cretaceous amber, repre- senting four different taxa, whereas eleven specimens have been recorded from Baltic amber, representing nine genera and ten species. A few, much younger, fossils have also been described from Dominican and Mexican ambers. Key words: Cretaceous, Paleocene, Miocene, Scorpiones. Santrauka: Straipsnyje pateikiama gintaruose rastu˛ fosiliniu˛ skorpionu˛ nuo apatines. kreidos iki mioceno apžvalga. Iš visu˛ nariuo- takoju˛ gintaruose skorpionu˛ randama reˇciausiai. Tik penki egzemplioriai yra žinomi iš kreidos gintaro. Jie priklauso keturiems skir- tingiems taksonams. O iš Baltijos gintaro yra aprašyta vienuolika egzemplioriu˛, priklausanˇciu˛ devynioms gentims ir dešimˇciai ru–šiu˛. Keletas daug jaunesniu˛ fosiliniu˛ skorpionu˛ taip pat buvo rasta Dominikos ir Meksikos gintaruose. Raktiniai žodžiai: Kreida, paleocenas, miocenas, retas. Introduction Baltic amber was the first to provide fossil scorpi- ons, at the beginning of the 19th century. Several new Scorpions are rare among the fossil arthropods discoveries have been the subject of studies since 1996 found in amber, although in recent years several speci- (LOURENÇO & WEITSCHAT 1996, 2000, 2001, 2005; mens have been described from Dominican and Mexi- LOURENÇO 2004; LOURENÇO et al. -

Succeeding Succession: Cosmic and Earthly Succession B.C.-17 A.D

Publication of this volume has been made possiblej REPEAT PERFORMANCES in partj through the generous support and enduring vision of WARREN G. MOON. Ovidian Repetition and the Metamorphoses Edited by LAUREL FULKERSON and TIM STOVER THE UNIVE RSITY OF WI S CON SIN PRE SS The University of Wisconsin Press 1930 Monroe Street, 3rd Floor Madison, Wisconsin 53711-2059 Contents uwpress.wisc.edu 3 Henrietta Street, Covent Garden London WC2E SLU, United Kingdom eurospanbookstore.com Copyright © 2016 The Board of Regents of the University of Wisconsin System Preface Allrights reserved. Except in the case of brief quotations embedded in critical vii articles and reviews, no part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrievalsystem, transmitted in any format or by any means-digital, electronic, Introduction: Echoes of the Past 3 mechanical, photocopying, recording, or otherwise-or conveyed via the LAUREL FULKERSON AND TIM STOVER Internetor a website without written permission of the University of Wisconsin Press. Rightsinquiries should be directed to rights@>uwpress.wisc.edu. 1 Nothing like the Sun: Repetition and Representation in Ovid's Phaethon Narrative 26 Printed in the United States of America ANDREW FELDHERR This book may be available in a digital edition. 2 Repeat after Me: The Loves ofVenus and Mars in Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data Ars amatoria 2 and Metamorphoses 4 47 BARBARA WElDEN BOYD Names: Fulkerson, Laurel, 1972- editor. 1 Stover, Tim, editor. Title: Repeat performances : Ovidian repetition and the Metamorphoses / 3 Ovid's Cycnus and Homer's Achilles Heel edited by Laurel Fulkerson and Tim Stover. PETER HESLIN Other titles: Wisconsin studies in classics. -

And Its Junior Synonym Tityus Antillanus (Thorell, 1877)

Francke, O. F. and J. A. Santiago-Blay. 1984. Redescription of 7Ityus crassimanus CrhomU,1877), and its junior synonymTityus antillanus (Thorell, 1877) (Scorpiones, Buthidae). J. Arachnol., 12:283-290. REDESCRIPTION OF TITYUS CRASSIMANUS (THORELL, 1877), AND ITS JUNIOR SYNONYMTITYUS ANTILLANUS (THORELL, 1877) (SCORPIONES, BUTHIDAE) Oscar F. Francke Departmentof BiologicalSciences TexasTech University Lubbock, Texas 79409 and Jorge1 A. Santiago-Blay Museode Biologia, Departmentode Biologia Univetsidadde Puerto Rico Rio Piedras, Puerto Rico 00931 ABSTRACT Tityus crassimanus(Thomll, 1877), originally described from one adult female from "Mexico," redescribed and its geographic distribution is revised to the Caribbeanisland of Hispaniola. Tityus antilla~us (Thorell, 1877), originally described from two juveniles from the "Antilles," is a junior synonymof T. crassimanus. Tityus crassin~nus appears to be most closely related to Tityus michelii Armas,from Puerto Rico. Htyus obtusus (Karsch, 1879), from Puerto Rico, has been confused with, and erroneously suspected of be/rig a junior synonymof T. crasgmaT:us. INTRODUCTION Thoreil (1877) describedsix species in the genusIsometrus Hemprich and Ehrenberg, four of them from the NewWorld. Isometrus fuscus Thorell, 1877, from Argentina was subsequentlydesignated the type species of the genusZabius Thorell, 1894. Isometrus stigmurusThorell, 1877, fromBrasil wastransferred to Tit)~s C. L. Karsch,where it is still considereda valid species (Louren~o1981). Isometruscrassimanus Thorell, 1877, fromMexico was also transferred to ~’tyus, whereit has remainedenigmatic (Hoffmann 1932) primarily because the genus ~tyus is otherwise unknownnorth of Costa Rica in either Central or North America(Pocock 1902, Lourenfoand Franckein press). Last, Isometrusantillanus Thorell, 1877, from "America(India Occidentalis)... (’ex Antil- lis’)," wasalso transferred to ~tyus, whereits identity and taxonomicstatus have been ’Present address: Deparlmentof Entomology,University of California, Berkeley, California 94720. -

Effects of Brazilian Scorpion Venoms on the Central Nervous System

Nencioni et al. Journal of Venomous Animals and Toxins including Tropical Diseases (2018) 24:3 DOI 10.1186/s40409-018-0139-x REVIEW Open Access Effects of Brazilian scorpion venoms on the central nervous system Ana Leonor Abrahão Nencioni1* , Emidio Beraldo Neto1,2, Lucas Alves de Freitas1,2 and Valquiria Abrão Coronado Dorce1 Abstract In Brazil, the scorpion species responsible for most severe incidents belong to the Tityus genus and, among this group, T. serrulatus, T. bahiensis, T. stigmurus and T. obscurus are the most dangerous ones. Other species such as T. metuendus, T. silvestres, T. brazilae, T. confluens, T. costatus, T. fasciolatus and T. neglectus are also found in the country, but the incidence and severity of accidents caused by them are lower. The main effects caused by scorpion venoms – such as myocardial damage, cardiac arrhythmias, pulmonary edema and shock – are mainly due to the release of mediators from the autonomic nervous system. On the other hand, some evidence show the participation of the central nervous system and inflammatory response in the process. The participation of the central nervous system in envenoming has always been questioned. Some authors claim that the central effects would be a consequence of peripheral stimulation and would be the result, not the cause, of the envenoming process. Because, they say, at least in adult individuals, the venom would be unable to cross the blood-brain barrier. In contrast, there is some evidence showing the direct participation of the central nervous system in the envenoming process. This review summarizes the major findings on the effects of Brazilian scorpion venoms on the central nervous system, both clinically and experimentally. -

Leto As Mother: Representations of Leto with Apollo and Artemis in Attic Vase Painting of the Fifth Century B.C

https://publications.dainst.org iDAI.publications ELEKTRONISCHE PUBLIKATIONEN DES DEUTSCHEN ARCHÄOLOGISCHEN INSTITUTS Dies ist ein digitaler Sonderdruck des Beitrags / This is a digital offprint of the article Lavinia Foukara Leto as Mother: Representations of Leto with Apollo and Artemis in Attic Vase Painting of the Fifth Century B.C. aus / from Archäologischer Anzeiger Ausgabe / Issue Seite / Page 63–83 https://publications.dainst.org/journals/aa/2027/6626 • urn:nbn:de:0048-journals.aa-2017-1-p63-83-v6626.5 Verantwortliche Redaktion / Publishing editor Redaktion der Zentrale | Deutsches Archäologisches Institut Weitere Informationen unter / For further information see https://publications.dainst.org/journals/aa ISSN der Online-Ausgabe / ISSN of the online edition 2510-4713 ISSN der gedruckten Ausgabe / ISSN of the printed edition Verlag / Publisher Ernst Wasmuth Verlag GmbH & Co. Tübingen ©2019 Deutsches Archäologisches Institut Deutsches Archäologisches Institut, Zentrale, Podbielskiallee 69–71, 14195 Berlin, Tel: +49 30 187711-0 Email: [email protected] / Web: dainst.org Nutzungsbedingungen: Mit dem Herunterladen erkennen Sie die Nutzungsbedingungen (https://publications.dainst.org/terms-of-use) von iDAI.publications an. Die Nutzung der Inhalte ist ausschließlich privaten Nutzerinnen / Nutzern für den eigenen wissenschaftlichen und sonstigen privaten Gebrauch gestattet. Sämtliche Texte, Bilder und sonstige Inhalte in diesem Dokument unterliegen dem Schutz des Urheberrechts gemäß dem Urheberrechtsgesetz der Bundesrepublik Deutschland. Die Inhalte können von Ihnen nur dann genutzt und vervielfältigt werden, wenn Ihnen dies im Einzelfall durch den Rechteinhaber oder die Schrankenregelungen des Urheberrechts gestattet ist. Jede Art der Nutzung zu gewerblichen Zwecken ist untersagt. Zu den Möglichkeiten einer Lizensierung von Nutzungsrechten wenden Sie sich bitte direkt an die verantwortlichen Herausgeberinnen/Herausgeber der entsprechenden Publikationsorgane oder an die Online-Redaktion des Deutschen Archäologischen Instituts ([email protected]). -

AND DID THOSE HOOVES Pan and the Edwardians

1 AND DID THOSE HOOVES Pan and the Edwardians By Eleanor Toland A thesis submitted to the Victoria University of Wellington in fulfilment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Arts in English Literature Victoria University of Wellington 2014 2 “….a goat’s call trembled from nowhere to nowhere…” James Stephens, The Crock of Gold, 1912 3 Contents Abstract………………………………………………………………………………………...4 Acknowledgements……………………………………………………………………………..5 Introduction: Pan and the Edwardians………………………………………………………….6 Chapter One: Pan as a Christ Figure, Christ as a Pan Figure…………………………………...17 Chapter Two: Uneasy Dreams…………………………………………..…………………......28 Chapter Three: Savage Wildness to Garden God………….…………………………………...38 Chapter Four: Culminations….................................................................................................................48 Chapter Five: The Prayer of the Flowers………………...…………………………………… 59 Conclusion…………………………………………………………………………………….70 Works Cited…………………………………………………………………………………...73 4 Acknowledgements My thanks to Lilja, Lujan, Saskia, Thomas, Emily, Eve, Mehdy, Eden, Margie, Katie, Anna P, the other Anna P, Hannah, Sarah, Caoilinn, Ronan, Kay, Angelina, Iain et Alana and anyone else from the eighth and ninth floor of the von Zedlitz building who has supplied a friendly face or a kind word. Your friendship and encouragement has been a fairy light leading me out of a perilous swamp. Thank you to my supervisors, Charles and Geoff, without whose infinite patience and mentorship this thesis would never have been finished, and whose supervision went far beyond the call of duty. Finally, thank you to my family for their constant support and encouragement. 5 Abstract A surprisingly high number of the novels, short stories and plays produced in Britain during the Edwardian era (defined in the terms of this thesis as the period of time between 1900 and the beginning of World War One) use the Grecian deity Pan, god of shepherds, as a literary motif. -

Athena ΑΘΗΝΑ Zeus ΖΕΥΣ Poseidon ΠΟΣΕΙΔΩΝ Hades ΑΙΔΗΣ

gods ΑΠΟΛΛΩΝ ΑΡΤΕΜΙΣ ΑΘΗΝΑ ΔΙΟΝΥΣΟΣ Athena Greek name Apollo Artemis Minerva Roman name Dionysus Diana Bacchus The god of music, poetry, The goddess of nature The goddess of wisdom, The god of wine and art, and of the sun and the hunt the crafts, and military strategy and of the theater Olympian Son of Zeus by Semele ΕΡΜΗΣ gods Twin children ΗΦΑΙΣΤΟΣ Hermes of Zeus by Zeus swallowed his first Mercury Leto, born wife, Metis, and as a on Delos result Athena was born ΑΡΗΣ Hephaestos The messenger of the gods, full-grown from Vulcan and the god of boundaries Son of Zeus the head of Zeus. Ares by Maia, a Mars The god of the forge who must spend daughter The god and of artisans part of each year in of Atlas of war Persephone the underworld as the consort of Hades ΑΙΔΗΣ ΖΕΥΣ ΕΣΤΙΑ ΔΗΜΗΤΗΡ Zeus ΗΡΑ ΠΟΣΕΙΔΩΝ Hades Jupiter Hera Poseidon Hestia Pluto Demeter The king of the gods, Juno Vesta Ceres Neptune The goddess of The god of the the god of the sky The goddess The god of the sea, the hearth, underworld The goddess of and of thunder of women “The Earth-shaker” household, the harvest and marriage and state ΑΦΡΟΔΙΤΗ Hekate The goddess Aphrodite First-generation Second- generation of magic Venus ΡΕΑ Titans ΚΡΟΝΟΣ Titans The goddess of MagnaRhea Mater Astraeus love and beauty Mnemosyne Kronos Saturn Deucalion Pallas & Perses Pyrrha Kronos cut off the genitals Crius of his father Uranus and threw them into the sea, and Asteria Aphrodite arose from them. -

The Phokikon and the Hero Archegetes (Plate54)

THE PHOKIKON AND THE HERO ARCHEGETES (PLATE54) A SHORT DISTANCE WEST of the Boiotian town of Chaironeia the Sacred Way I Lcrossed the border into Phokis. The road went past Panopeus and on toward Daulis before turning south toward the Schiste Odos and, eventually, Delphi (Fig. 1). To reach the famous crossroads where Oidipos slew his father, the Sacred Way first had to pass through the valley of the Platanias River. In this valley, on the left side of the road, was the federal meeting place of the Phokians, the Phokikon.1 This is one of the few civic buildings from antiquity whose internal layout is described by an eyewitness.2 Pausanias says, Withrespect to size the buildingis a largeone, and withinit thereare columnsstanding along its length; steps ascend from the columnsto each wall, and on these steps the delegatesof the Phokianssit. At the far end there are neithercolumns nor steps, but a statuegroup of Zeus, Athena, and Hera; the statueof Zeus is enthroned,flanked by the goddesses,with the statueof Athenastanding on the left (1O.5.2).3 Frazersuggested that the interior of the building resembledthe Thersilion at Megalopolis.4 The location of a federal assembly hall so close to the border with Boiotia, an often hostile neighbor, seems puzzling, but given the shape of the entire territory of Phokis, the position of the Phokikonmakes sense (Fig. 2). As Philippson noted, "Die antike Landschaft Phokis ist nicht nattirlichbegrenzt und kein geographisch einheitliches Gebiet."5 Ancient Phokis was dominated by Mount Parnassos, and the Phokians inhabited two distinct 1 An earlier draft of this paper was delivered at the 92nd Annual Meeting of the Archaeological Institute of America (San Francisco 1990; abstract, AJA 1991, pp. -

Lecture 9 Good Morning and Welcome to LLT121 Classical Mythology

Lecture 9 Good morning and welcome to LLT121 Classical Mythology. In our last exciting class, we were discussing the various sea gods. You’ll recall that, in the beginning, Gaia produced, all by herself, Uranus, the sky, Pontus, the sea and various mountains and whatnot. Pontus is the Greek word for “ocean.” Oceanus is another one. Oceanus is one of the Titans. Guess what his name means in ancient Greek? You got it. It means “ocean.” What we have here is animism, pure and simple. By and by, as Greek civilization develops, they come to think of the sea as ruled by this bearded god, lusty, zesty kind of god. Holds a trident. He’s seriously malformed. He has an arm growing out of his neck this morning. You get the picture. This is none other than the god Poseidon, otherwise known to the Romans as Neptune. One of the things that I’m going to be mentioning as we meet the individual Olympian gods, aside from their Roman names—Molly, do you have a problem with my drawing? Oh, that was the problem. Okay, aside from their Roman names is also their quote/unquote attributes. Here’s what I mean by attributes: recognizable features of a particular god or goddess. When you’re looking at, let’s say, ancient Greek pottery, all gods and goddesses look pretty much alike. All the gods have beards and dark hair. All the goddesses have long, flowing hair and are wearing dresses. The easiest way to tell them apart is by their attributes. -

Promethean and Titian Hepatic Regeneration, Unveiling Hepar's

Review Article iMedPub Journals Journal of Universal Surgery 2017 http://www.imedpub.com ISSN 2254-6758 Vol. 5 No. 2: 6 DOI: 10.21767/2254-6758.100074 Promethean and Titian Hepatic Gregory Tsoucalas1, Andreas Kapsoritakis2, Regeneration, Unveiling Hepar’s Myth– Spyros Potamianos2 and Post Mortem Observation, Surgical Markos Sgantzos1,3 Ascertainment, or just Fiction? 1 Faculty of Medicine, University of Thessaly, Larissa, Greece 2 Department of Gastroenterology, University of Thessaly, Larissa, Greece Abstract 3 Department of Anatomy, University of Two ancient Greek myths, the sad stories of Prometheus and Tityus, suggest that Thessaly, Larissa, Greece ancient Greek medico-philosophers observed hepar’s ability to regenerate after a partial excision. For some, hepar was the centre of the soul and an important visceral organ for human’s body homeostasis. Although facts such as war surgery, Corresponding author: Gregory Tsoucalas dissections, both human and animal, autopsies and abdominal surgery (hepatic abscesses and malignancies) testify that ancient Greeks had some knowledge on [email protected] hepar’s anatomy and physiology, there is no clear reference that they did witness the hepatic regeneration. History of Medicine, Faculty of Medicine, Keywords: Hepar; Hepatoscopy; Lives’ regeneration; Prometheus; Tityus; University of Thessaly, Larissa, Greece. Abdominal surgery Tel: 00306945298205 Received: February 12, 2017; Accepted: February 15, 2017; Published: February 24, 2017 Citation: Tsoucalas G, Kapsoritakis A, Potamianos S, et al. Promethean and Titian Hepatic Regeneration, Unveiling Hepar’s Introduction Myth–Post Mortem Observation, Surgical In Greek antiquity human and animal liver played an important Ascertainment, or just Fiction? J Univer role both in daily life and in divine-spiritual medicine.