2. Land and Water Management Issues in the Lower Shoalhaven River Catchment

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

October 2010

1 ASHET News October 2010 Volume 3, number 4 ASHET News October 2010 Newsletter of the Australian Society for History of Engineering and Technology th Reservoir, was approved in 1938 and completed in 1940. Preliminary University of Queensland’s 100 geological work for a dam on the Warragamba finally commenced in Anniversary 1942. A dam site was selected in 1946. The University of Queensland and its engineering school are celebrating Building the dam their 100th anniversary this year. Naming the members of the first Senate Excavation work on the Warragamba Dam started in 1948 and actual in the Government Gazette of 16 April 1910 marked the foundation of the construction of the dam began in 1950. It was completed in 1960. It was University. It was Australia’s fifth university. built as a conventional mass concrete dam, 142 metres high and 104 The University’s foundation professor of engineering was Alexander metres thick at the base. For the first time in Australia, special measures James Gibson, Born in London in 1876, he was educated at Dulwich were taken to reduce the effects of heat generated during setting of the College and served an apprenticeship with the Thames Ironworks, concrete; special low-heat cement was used, ice was added to the concrete Shipbuilding and Engineering Company. He became an Assocaite during mixing, and chilled water was circulated through embedded pipes Member of the Institution of Civil Engineers in 1899. He migrated to during setting of the concrete. Shanghai in that year, and came to Sydney in 1900, where he became a The dam was designed to pass a maximum flow of 10,000 cubic fitter at Mort’s Dock. -

Sydney Water in 1788 Was the Little Stream That Wound Its Way from Near a Day Tour of the Water Supply Hyde Park Through the Centre of the Town Into Sydney Cove

In the beginning Sydney’s first water supply from the time of its settlement Sydney Water in 1788 was the little stream that wound its way from near A day tour of the water supply Hyde Park through the centre of the town into Sydney Cove. It became known as the Tank Stream. By 1811 it dams south of Sydney was hardly fit for drinking. Water was then drawn from wells or carted from a creek running into Rushcutter’s Bay. The Tank Stream was still the main water supply until 1826. In this whole-day tour by car you will see the major dams, canals and pipelines that provide water to Sydney. Some of these works still in use were built around 1880. The round trip tour from Sydney is around 350 km., all on good roads and motorway. The tour is through attractive countryside south Engines at Botany Pumping Station (demolished) of Sydney, and there are good picnic areas and playgrounds at the dam sites. source of supply. In 1854 work started on the Botany Swamps Scheme, which began to deliver water in 1858. The Scheme included a series of dams feeding a pumping station near the present Sydney Airport. A few fragments of the pumping station building remain and can be seen Tank stream in 1840, from a water-colour by beside General Holmes Drive. Water was pumped to two J. Skinner Prout reservoirs, at Crown Street (still in use) and Paddington (not in use though its remains still exist). The ponds known as Lachlan Swamp (now Centennial Park) only 3 km. -

History of Sydney Water

The history of Sydney Water Since the earliest days of European settlement, providing adequate water and sewerage services for Sydney’s population has been a constant challenge. Sydney Water and its predecessor, the Metropolitan Water Sewerage and Drainage Board, has had a rich and colourful history. This history reflects the development and growth of Sydney itself. Over the past 200 years, Sydney’s unreliable rainfall has led to the development of one of the largest per capita water supplies in the world. A truly reliable water supply was not achieved until the early 1960s after constructing Warragamba Dam. By the end of the 20th Century, despite more efficient water use, Sydney once again faced the prospect of a water shortage due to population growth and unreliable rainfall patterns. In response to this, the NSW Government, including Sydney Water, started an ambitious program to secure Sydney’s water supplies. A mix of options has been being used including water from our dams, desalination, wastewater recycling and water efficiency. Timeline 1700s 1788 – 1826 Sydney was chosen as the location for the first European settlement in Australia, in part due to its outstanding harbour and the availability of fresh water from the Tank Stream. The Tank Stream remained Sydney’s main water source for 40 years. However, pollution rapidly became a problem. A painting by J. Skinner Prout of the Tank Stream in the 1840s 1800s 1880 Legislation was passed under Sir Henry Parkes, as Premier, which constitutes the Board of Water Supply and Sewerage. 1826 The Tank Stream was abandoned as a water supply because of pollution from rubbish, sewage and runoff from local businesses like piggeries. -

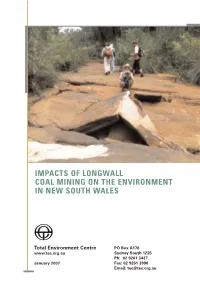

Impacts of Longwall Coal Mining on the Environment in New South Wales

IMPACTS OF LONGWALL COAL MINING ON THE ENVIRONMENT IN NEW SOUTH WALES Total Environment Centre PO Box A176 www.tec.org.au Sydney South 1235 Ph: 02 9261 3437 January 2007 Fax: 02 9261 3990 Email: [email protected] CONTENTS 01 OVERVIEW 3 02 BACKGROUND 5 2.1 Definition 5 2.2 The Longwall Mining Industry in New South Wales 6 2.3 Longwall Mines & Production in New South Wales 2.4 Policy Framework for Longwall Mining 6 2.5 Longwall Mining as a Key Threatening Process 7 03 DAMAGE OCCURRING AS A RESULT OF LONGWALL MINING 9 3.1 Damage to the Environment 9 3.2 Southern Coalfield Impacts 11 3.3 Western Coalfield Impacts 13 3.4 Hunter Coalfield Impacts 15 3.5 Newcastle Coalfield Impacts 15 04 LONGWALL MINING IN WATER CATCHMENTS 17 05 OTHER EMERGING THREATS 19 5.1 Longwall Mining near National Parks 19 5.2 Longwall Mining under the Liverpool Plains 19 5.3 Longwall Top Coal Caving 20 06 REMEDIATION & MONITORING 21 6.1 Avoidance 21 6.2 Amelioration 22 6.3 Rehabilitation 22 6.4 Monitoring 23 07 KEY ISSUES AND RECOMMENDATIONS 24 7.1 The Approvals Process 24 7.2 Buffer Zones 26 7.3 Southern Coalfields Inquiry 27 08 APPENDIX – EDO ADVICE 27 EDO Drafting Instructions for Legislation on Longwall Mining 09 REFERENCES 35 We are grateful for the support of John Holt in the production of this report and for the graphic design by Steven Granger. Cover Image: The now dry riverbed of Waratah Rivulet, cracked, uplifted and drained by longwall mining in 2006. -

Wambo Coal Pty Limited

WAMBO COAL PTY LIMITED SOUTH BATES EXTENSION UNDERGROUND MINE EXTRACTION PLAN LONGWALLS 21 TO 24 ATTACHMENT 2 RELEVANT CONSULTATION RECORDS Nicole Dobbins Senior Environmental Advisor Wambo Coal Pty Ltd PMB 1 Singleton NSW 2330 1 April 2021 Dear Ms Dobbins Wambo Underground Coal Mine (DA 305-7-2003-i) Extraction Plan for Longwalls 21 to 24 I refer to the Extraction Plan for Longwalls (LWs) 21 to 24, which has been prepared in accordance with condition B7 of Schedule 2 of the above development consent and revised to address the Department’s comments dated 15 January 2021, to include a revised mining schedule, and to include a number of recently approved supplementary management plans. The Department has carefully reviewed the Extraction Plan (including its various sub-plans) and is satisfied that it addresses the relevant requirements of the development consent (see Attachment A). Accordingly, the Secretary has approved the Extraction Plan (Revision B, dated January 2021), subject to the following administrative amendments: • The fourth paragraph on page 26 of the Extraction Plan requires re-wording and states incorrect water volumes for seepage from North Wambo Creek into the underground workings. This same information is presented in paragraph 8 on page 17 of the approved Water Management Plan that forms Appendix A of the Extraction Plan. Please amend as per the email sent to the Department on 31 March 2021. • The third paragraph on page 27 states that mitigation measures to manage predicted subsidence impacts on North Wambo Creek are summarised in Section 5. However, Section 5 of the EP is the reference section. -

GIPA Contracts As at 3.2.2020.Xlsx

WaterNSW GIPA Contract Register ‐ as at 3.2.2020 Right to Information Officer [email protected] Estimated Amount Payable Provisions which the Contractor is to Receive Particulars of Any Related Contract Effective Contract Expiry Particulars of the Project, G&S or to the Contractor (GST Provisions under which the Amount Summary of the Criteria for Payment for Providing Operational/Maintenance Contract No. Contract Title Name of Contractor Business Address of Contractor Entities Date Date Property Exclusive) Payable may be Varied Provisions Regarding Renegotiation Method of Tendering Assessment Services The evaluation criteria Variations provisions are as per Master comprised 80% technical Professional Services Agreement No. criteria and 20% price 05365DD0 ‐ The Master Services criteria. The technical criteria Agreement establishes pre‐agreed terms, Renegotiation provisions are as per included methodology and with services to be established and agreed Master Professional Services Agreement program, core team selection through service orders (following standard No. 05365DD0 ‐ The Master Services and availability, briefing procurement processes). Under clause 10, Agreement provides for the ability of quality and content, key WaterNSW may direct variations, payable either party to terminate the agreement personnel and sub‐ The Services are for consultancy and professional 05365DD0‐ LEVEL 8, 180 LONSDALE STREET Engineering Consulting and Advisory according to the agreed schedule of rates in the event of wind‐up, liquidation or contractors, experience and services. There are no provisions for outsourced 2019/780588 Drought Response Projects Delivery Partner GHD PTY LTD MELBOURNE VIC 3000 None 22/07/2019 31/12/2019 Services $1,363,636 or otherwise agreed. default of obligations. Select Tender innovation. -

Government Gazette of the STATE of NEW SOUTH WALES Number 117 Friday, 24 September 2010 Published Under Authority by Government Advertising

4623 Government Gazette OF THE STATE OF NEW SOUTH WALES Number 117 Friday, 24 September 2010 Published under authority by Government Advertising LEGISLATION Online notification of the making of statutory instruments Week beginning 13 September 2010 THE following instruments were officially notified on the NSW legislation website (www.legislation.nsw.gov.au) on the dates indicated: Proclamations commencing Acts Crimes (Sentencing Legislation) Amendment (Intensive Correction Orders) Act 2010 No. 48 (2010-532) – published LW 17 September 2010 National Parks and Wildlife Amendment (Visitors and Tourists) Act 2010 No. 41 (2010-533) – published LW 17 September 2010 Regulations and other statutory instruments Crimes (Sentencing Procedure) Amendment (Transitional) Regulation 2010 (2010-534) – published LW 17 September 2010 Occupational Health and Safety Amendment (Penalty Notice Offences) Regulation 2010 (2010-535) – published LW 17 September 2010 Environmental Planning Instruments Greater Taree Local Environmental Plan 2010 (Amendment No. 2) (2010-536) – published LW 17 September 2010 Gunnedah Local Environmental Plan 1998 (Amendment No. 19) (2010-537) – published LW 17 September 2010 Hawkesbury Local Environmental Plan 1989 (Amendment No. 157) (2010-538) – published LW 17 September 2010 Maitland Local Environmental Plan 1993 (Amendment No. 106) (2010-539) – published LW 17 September 2010 4624 LEGISLATION 24 September 2010 Assents to Acts ACTS OF PARLIAMENT ASSENTED TO Legislative Assembly Office, Sydney, 15 September 2010 IT is hereby notified, for general information, that Her Excellency the Governor has, in the name and on behalf of Her Majesty, this day assented to the undermentioned Acts passed by the Legislative Assembly and Legislative Council of New South Wales in Parliament assembled, viz.: Act No. -

Banking Act Unclaimed Money As at 31 December 2007

Commonwealth of Australia Gazette No. ASIC 40A/08, Wednesday, 21 May 2008 Published by ASIC ASIC Gazette Contents Banking Act Unclaimed Money as at 31 December 2007 RIGHTS OF REVIEW Persons affected by certain decisions made by ASIC under the Corporations Act 2001 and the other legislation administered by ASIC may have rights of review. ASIC has published Regulatory Guide 57 Notification of rights of review (RG57) and Information Sheet ASIC decisions – your rights (INFO 9) to assist you to determine whether you have a right of review. You can obtain a copy of these documents from the ASIC Digest, the ASIC website at www.asic.gov.au or from the Administrative Law Co-ordinator in the ASIC office with which you have been dealing. ISSN 1445-6060 (Online version) Available from www.asic.gov.au ISSN 1445-6079 (CD-ROM version) Email [email protected] © Commonwealth of Australia, 2008 This work is copyright. Apart from any use permitted under the Copyright Act 1968, all rights are reserved. Requests for authorisation to reproduce, publish or communicate this work should be made to: Gazette Publisher, Australian Securities and Investment Commission, GPO Box 9827, Melbourne Vic 3001 ASIC GAZETTE Commonwealth of Australia Gazette ASIC 40A/08, Wednesday, 21 May 2008 Banking Act Unclaimed Money Page 2 of 463 Specific disclaimer for Special Gazette relating to Banking Unclaimed Monies The information in this Gazette is provided by Authorised Deposit-taking Institutions to ASIC pursuant to the Banking Act (Commonwealth) 1959. The information is published by ASIC as supplied by the relevant Authorised Deposit-taking Institution and ASIC does not add to the information. -

Healthy Catchments Quality Water Always

Sydney Catchment Authority | Annual Report 0607 I Healthy catchments Quality water Always Sydney Catchment Authority | Annual Report 2006–07 Figure 1: SCA drinking water catchments Sydney Catchment Authority | Annual Report 2006–07 Sydney Catchment Authority 1 Annual Report 2006–07 Contents Letter to the Minister 2 About the SCA 4 Our key areas of performance 7 Report from the Chairman 8 Report from the Chief Executive 10 Corporate governance 14 Our organisation 16 KRA 01 Threats to water quality minimised 19 KRA 02 Sustainable and reliable water supply 29 KRA 03 Commercial success 41 KRA 04 Building and sharing knowledge 49 KRA 05 Results through relationships 59 KRA 06 Dynamic, supportive workplace 67 KRA 07 Quality systems and processes 69 Financial reporting 76 Appendices 135 SCA Division Report 157 Glossary 200 Acronyms 201 Annual Report 2006–07 compliance checklist 202 Sydney SydneyCatchment Catchment Authority Authority | Annual | ReportAnnual 2006Report–07 2006–07 2 Sydney Catchment Authority | Annual Report 2006–07 Healthy catchments, quality water – always 3 Above: The Nepean/Avon deep water access project involved constructing a new pumping station at the base of Nepean Dam and a two kilometre pipeline to deliver water to Avon Dam, which supplies the Illawarra. Sydney Catchment Authority | Annual Report 2006–07 About the SCA The Sydney Catchment Authority SCA business plan principles 4 Annual Report 2006–07 Our vision The 2006–07 annual reports for the Sydney Catchment Healthy catchments, quality water – always Authority (SCA) and Sydney Catchment Authority Division of the Government Service (SCA Division) Our key values provide details of organisational performance over the past year. -

Copy of Privately Owned Dams

Capacity No of dam Name of dam Town nearest Province (1000 m³) A211/40 ASH TAILINGS DAM NO.2 MODDERFONTEIN GT 80 A211/41 ASH TAILINGS DAM NO.5 MODDERFONTEIN GT 68 A211/42 KNOPJESLAAGTE DAM 3 VERWOERDBURG GT 142 A211/43 NORTH DAM KEMPTON PARK GT 245 A211/44 SOUTH DAM KEMPTON PARK GT 124 A211/45 MOOIPLAAS SLIK DAM ERASMIA PRETORIA GT 281 A211/46 OLIFANTSPRUIT-ONDERSTE DAM OLIFANTSFONTEIN GT 220 A211/47 OLIFANTSPRUIT-BOONSTE DAM OLIFANTSFONTEIN NW 450 A211/49 LEWIS VERWOERDBURG GT 69 A211/51 BRAKFONTEIN RESERVOIR CENTURION GT 423 A211/52 KLIPFONTEIN NO1 RESERVOIR KEMPTON PARK GT 199 A211/53 KLIPFONTEIN NO2 RESERVOIR KEMPTON PARK GT 259 A211/55 ZONKIZIZWE DAM JOHANNESBURG GT 150 A211/57 ESKOM CONVENTION CENTRE DAM JOHANNESBURG GT 80 A211/59 AALWYNE DAM BAPSFONTEIN GT 132 A211/60 RIETSPRUIT DAM CENTURION GT 51 A211/61 REHABILITATION DAM 1 BIRCHLEIGH NW 2857 A212/40 BRUMA LAKE DAM JOHANNESBURG GT 120 A212/54 JUKSKEI SLIMES DAM HALFWAY HOUSE GT 52 A212/55 KYNOCH KUNSMIS LTD GIPS AFVAL DAM KEMPTON PARK GT 3000 A212/56 MODDERFONTEIN FACTORY DAM NO. 1 EDENVALE GT 550 A212/57 MODDERFONTEIN FACTORY DAM NO.2 MODDERFONTEIN GT 28 A212/58 MODDERFONTEIN FACTORY DAM NO. 3 EDENVALE GT 290 A212/59 MODDERFONTEIN FACTORY DAM NO. 4 EDENVALE GT 571 A212/60 MODDERFONTEIN FACTORY DAM NO.5 MODDERFONTEIN GT 30 A212/65 DOORN RANDJIES DAM PRETORIA GT 102 A212/69 DARREN WOOD JOHANNESBURG GT 21 A212/70 ZEVENFONTEIN DAM 1 DAINFERN GT 72 A212/71 ZEVENFONTEIN DAM 2 DAIRNFERN GT 64 A212/72 ZEVENFONTEIN DAM 3 MiDRAND GT 58 A212/73 BCC DAM AT SECOND JOHANNESBURG GT 39 A212/74 DW6 LEOPARD DAM LANSERIA NW 180 A212/75 RIVERSANDS DAM DIEPSLOOT GT 62 A213/40 WEST RAND CONS. -

Towards a New Philosophy of Engineering

Chapter 7 – Case Study : Sydney’s Water System… Chapter 7 : Case Study – Sydney’s Water System 7.1 Introduction The purpose of the case study is to consider and test three key propositions of this thesis in the context of a real problem situation. First is to demonstrate that the problem typology described in Chapter 3, regarding the Type 3 problem, can be identified and, importantly, that there is value in recognising this type of problem. Second is to demonstrate the benefit of using the problem-structuring approach developed in Chapter 6, through its practical application to a real Type 3 problem. In this case the problem is consideration of the planning process for the development of the water supply system in a large metropolis (the metropolis being Sydney, Australia). And third is to compare this novel approach with established methodologies used in major planning initiatives to determine whether the problem-structuring approach developed here provides any clearly identifiable advantages over existing approaches. If so, the aim is then to propose a more comprehensive, effective approach to the process of major infrastructure planning. In order to achieve these three aims, the case study is presented in two distinct parts: first, is the application of the problem-structuring approach prospectively in order to guide the planning process; and second, is to use the problem-structuring approach retrospectively to critique alternative approaches. 7.2 Case Study structure Part A is a prospective application of the problem-structuring approach in its entirety. This part of the case study was based on a project managed by the Warren Centre for Advanced Engineering at the University of Sydney. -

A Case Study: Prospect Reservoir at Western Sydney

PLEASE TYPE THE UNIVERSITY OF NEW SOUTH WALES Thesis/Dissertation Sheet Surname or Family name: Zambre First name: Fallavi Other name/s: Abbreviation for degree as given in the University calendar: School: UNSW Faculty: Built Environment Title: Proposing A Cultural Landscape Paradigm: A Case study: Prospect Reservoir at Western Sydney. Abstract 350 words maximum: (PLEASE TYPE) The study sets out to investigate and question the Burra Charter, its interpretations and approaches for protection of cultural landscape in Australia. While achieving the preservation of state and national icons, the Charter has overlooked the meanings and values of heritage landscape. Drawing on the field of landscape theory, my research seeks to extend the theoretical approach to study of the cultural landscape. Thus, this thesis proposes the cultural landscape paradigm (CLP) which provides a framework to interpret the inherent values of cultural landscape based on ecological, experiential and narrative approaches. Towards this goal, the research attempts to demonstrate and apply the CLP by conducting a case study of the culturally significant landscape of Prospect Reservoir in western Sydney. The study is undertaken with the help of a detailed analysis of landscape elements, historic documents, narrative references, personal observations and photographs. I found that although the site has been conserved on the principles of the Burra Charter, the regional identity and sense of place has not been taken into account. Over time, degradation of the ecosystem has changed the ecological, narrative and experiential quality of the place. Thus the landscape reflects the Burra Charter's values of national, state significance, and dominance in portraying a story of European past, with limited concern for aboriginal cultural landscape.