The Autobiography of Rear Admiral John A. Dahlgren

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Census of the State of Michigan, 1894

(Rmmll mmvmxi^ fibatg THE GIFT OF l:\MURAM.--kLl'V'^'-.':^-.y.yi m. .cPfe£.. Am4l im7 CORNELL UNIVERSITY LIBRARV Cornell University Library The original of this book is in the Cornell University Library. There are no known copyright restrictions in the United States on the use of the text. http://www.archive.org/details/cu31924072676715 CENSUS STATE OF MICHIGAN 1894 SOLDIERS, SAILORS AND MARINES YOLTJME ni COMPrLED AND PUBLISHBD BY WASHINGTON GARDNER, SECRETARY OF STATE In accordance with an Act of the Legrislature, approved May 31, 1893 BY AUTHOEITY LANSING EOBEET SMITH & CO., STATE PEINTEES AND BINDEES CONTENTS. Table 1. The United States soldiers of the civil war distinguished as aative and foreig:n-born by ages and civil condition. Table 2. The United States soldiers of the civil war diatingnisbed as native and foreign-bom by ages in periods of years. Table 3. The United States soldiers of the civil war distinguished as native and foreign-born by civil condition. Table i. The Confederate soldiers by ages. Table 5. The Confederate soldiers distingnished as native and foreign-born and by civil condition. Table 6. The United States soldiers of the Mexican war distinguished as native and foreign-bom and by civil condition. Table 7. The United States marines distinguished as native and foreign-bom and by civil condition. Table 8. By nativity and by ages in periods of years, the U. S. soldiers, sailors and marines who were sick or temporarily disabled on the day of the enumerator's visit, together with the nature of the sickness or disability. -

“What Are Marines For?” the United States Marine Corps

“WHAT ARE MARINES FOR?” THE UNITED STATES MARINE CORPS IN THE CIVIL WAR ERA A Dissertation by MICHAEL EDWARD KRIVDO Submitted to the Office of Graduate Studies of Texas A&M University in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY May 2011 Major Subject: History “What Are Marines For?” The United States Marine Corps in the Civil War Era Copyright 2011 Michael Edward Krivdo “WHAT ARE MARINES FOR?” THE UNITED STATES MARINE CORPS IN THE CIVIL WAR ERA A Dissertation by MICHAEL EDWARD KRIVDO Submitted to the Office of Graduate Studies of Texas A&M University in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY Approved by: Chair of Committee, Joseph G. Dawson, III Committee Members, R. J. Q. Adams James C. Bradford Peter J. Hugill David Vaught Head of Department, Walter L. Buenger May 2011 Major Subject: History iii ABSTRACT “What Are Marines For?” The United States Marine Corps in the Civil War Era. (May 2011) Michael E. Krivdo, B.A., Texas A&M University; M.A., Texas A&M University Chair of Advisory Committee: Dr. Joseph G. Dawson, III This dissertation provides analysis on several areas of study related to the history of the United States Marine Corps in the Civil War Era. One element scrutinizes the efforts of Commandant Archibald Henderson to transform the Corps into a more nimble and professional organization. Henderson's initiatives are placed within the framework of the several fundamental changes that the U.S. Navy was undergoing as it worked to experiment with, acquire, and incorporate new naval technologies into its own operational concept. -

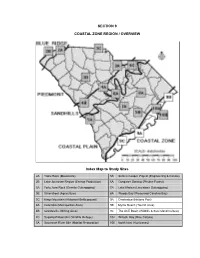

Coastal Zone Region / Overview

SECTION 9 COASTAL ZONE REGION / OVERVIEW Index Map to Study Sites 2A Table Rock (Mountains) 5B Santee Cooper Project (Engineering & Canals) 2B Lake Jocassee Region (Energy Production) 6A Congaree Swamp (Pristine Forest) 3A Forty Acre Rock (Granite Outcropping) 7A Lake Marion (Limestone Outcropping) 3B Silverstreet (Agriculture) 8A Woods Bay (Preserved Carolina Bay) 3C Kings Mountain (Historical Battleground) 9A Charleston (Historic Port) 4A Columbia (Metropolitan Area) 9B Myrtle Beach (Tourist Area) 4B Graniteville (Mining Area) 9C The ACE Basin (Wildlife & Sea Island Culture) 4C Sugarloaf Mountain (Wildlife Refuge) 10A Winyah Bay (Rice Culture) 5A Savannah River Site (Habitat Restoration) 10B North Inlet (Hurricanes) TABLE OF CONTENTS FOR SECTION 9 COASTAL ZONE REGION / OVERVIEW - Index Map to Coastal Zone Overview Study Sites - Table of Contents for Section 9 - Power Thinking Activity - "Turtle Trot" - Performance Objectives - Background Information - Description of Landforms, Drainage Patterns, and Geologic Processes p. 9-2 . - Characteristic Landforms of the Coastal Zone p. 9-2 . - Geographic Features of Special Interest p. 9-3 . - Carolina Grand Strand p. 9-3 . - Santee Delta p. 9-4 . - Sea Islands - Influence of Topography on Historical Events and Cultural Trends p. 9-5 . - Coastal Zone Attracts Settlers p. 9-5 . - Native American Coastal Cultures p. 9-5 . - Early Spanish Settlements p. 9-5 . - Establishment of Santa Elena p. 9-6 . - Charles Towne: First British Settlement p. 9-6 . - Eliza Lucas Pinckney Introduces Indigo p. 9-7 . - figure 9-1 - "Map of Colonial Agriculture" p. 9-8 . - Pirates: A Coastal Zone Legacy p. 9-9 . - Charleston Under Siege During the Civil War p. 9-9 . - The Battle of Port Royal Sound p. -

GUNS Magazine January 1959

JANUARY 1959 SOc fIIEST III THE fllUUlS finD HUNTING- SHOOTING -ADVENTURE 1958 NATIONAL DOUBLES CHAMPION JOE HIESTAND • Ohio State Champion-9 times • Amateur Clay Target Champion of America-4 times • Doubles Champion of America 3 times • High Over All Champion-7 times • Hiestand has the remarka'ble record of having broken 200 out of 200 fifty times. • Hiestand has the world's record of having broken 1,404 registered targets straight without missing a one. Champions like Joe Hiestand de pend on the constant performance of CCI primers. The aim of CCI Champions like Joe Hiestand de pend on the constant performance of CCI primers. The aim of cel is to continue to produce the finest quality primers for Ameri can shooters. .' Rely on CCI PRIMERS American Made ~ Large and Small Rifle, 8.75 per M Large and Small Pistol, 8.75 per M Shotshell Caps, 8.75 per M Shotshell, 15.75 per M ~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~ ~~~~~ ~ ~~~~~~~~~~~~~~ ~ TWO IDEAL CHRISTMAS GIFTS ... ~ ·tgfJi'Yo, ~ , ~ ~ ; ,.;- '.. •22,iSPRINCiFIELD CONVERSION UNIT .fSmash;n,g Fits Any M 1903 Springfield " j poWer BARREL INSERT MAGAZINE PERFECT FOR TRAININ~ I YOUNGSTERS AT LOW COST 12 SPRINGFIELD BOLT Only $34.50 ppd. (Extra magazine-$1.75) ~~f:~~"~? .~O.~Et~e t';p.er. The ~ ••nd ee..4 --.--- ~ ,~ :.'t =.r ' ~~~in~~ ;n(l ~:::~ u: i ~~ i~: »)l~~~:~~~s .•-:: isst:lnd~usrr;-e:~ . Id eal for practice using" .22 l.r, ammo. Think of the ]noney you Save . W hy pu c away your .22 Target p i at ol l ines, ru g . ge~ mct a~ alloy Ir- blue- Sp ringfie ld spor rer wh en high pow er season is ove r, quick ly conve rt it in to a super accurate ~~i~~ c:: ~n~~p er5~:: :~1n ef~ ~pa:i;~d Ol~ 5~~~ l~O~:~ot:i "Man-sized" .22 re peater. -

Harriet Lane Steve Schulze Camp Commander

SONS OF UNION VETERANS OF THE CIVIL WAR Lt. Commander Edward Lea U.S.N. – Camp Number 2 Harriet Lane *************************************************************************************** Summer 2007 Volume 14 Number 2 ************************************************************************************** From the Commander’s Tent Here we go again. Its summer with all the bustle and activity associated with the season. School is out, everyone’s looking forward to their vacations and the pace of life in some ways is even more frantic than during the other seasons of the year. The Camp just completed one of its most important evolutions - Memorial Day. We had nine Brothers at the National Cemetery, with eight in period uniform. I think this is the best uniformed turnout we’ve ever had, at least in my memory. We are also in the process of forming a unit of the Sons of Veteran’s Reserve. We have ten prospective members from our Camp. Brother Dave LaBrot is the prospective commanding officer. All we are waiting for is for the James J. Byrne Camp #1 to send down their seven applications so the paperwork can be turned in. We should then soon have the unit up and running. I hope that even more Brothers will join as we get rolling. I have been watching with great interest the way the level of awareness of and the desire to learn about the Civil War in particular, and the 1860’s in general, has been growing throughout the nation during the last few years. In part this may be because we are coming up upon another milestone period (the 150th anniversary). But also I think more people are realizing the importance of the events of that era and the extent that we are still being affected by them today. -

All Saints Church, Waccamaw Photo Hy Ski1,11Er

All Saints Church, Waccamaw Photo hy Ski1,11er ALL SAINTS' CHURCH, WACCAMAW THE PARISH: THE· PLACE: THE PEOPLE. ---•-•.o• ◄ 1739-1948 by HENRY DeSAUSSURE BULL Published by The Historical Act-ivities Committee of the South Carolina Sociefy o'f' Colonial Dames of America 1948 fl'IIINTED 8Y JOHN J. FURLONG a SONS CHARLESTON, 5, C, This volume is dedicated to the memo,-y of SARAH CONOVER HOLMES VON KOLNITZ in grateful appr.eciation of her keen interest in the history of our State. Mrs. Von Kolnit& held the following offices in the South Carolina Society of Colonial Dames of America : President 193S-1939 Honorary President 1939-1943 Chairman of Historic Activities Committte 1928-1935 In 1933 she had the honor of being appointed Chairman of Historic Activities Committee of the National Society of Colonial Dames of America ·which office she held with con spicuous ability until her death on April 6th 1943. CHURCH, W ACCAMA ALL SAINTS' • 'Ai 5 CHAPTER I - BEGINNING AND GROWTH All Saint's Parish includes the whole of vVaccamaw peninsula, that narrow tongue of land lying along the coast of South Caro~ lina, bounded on the east by the Atlantic and on the \Vest by the Waccamaw River which here flo\vs almost due south and empties into Winyah Bay. The length of the "N eek" from Fraser's Point to the Horry County line just north of Murrell's Inlet is about thirty miles and the width of the high land varies f rorii two to three miles. The :place takes its name from the \Vac~ camaws, a small Indian tribe of the locality who belonged ·to a loose conf ederacv.. -

Title 21 Food and Drugs Part 500 to 599

Title 21 Food and Drugs Part 500 to 599 Revised as of April 1, 2014 Containing a codification of documents of general applicability and future effect As of April 1, 2014 Published by the Office of the Federal Register National Archives and Records Administration as a Special Edition of the Federal Register VerDate Mar<15>2010 09:09 Aug 04, 2014 Jkt 232075 PO 00000 Frm 00001 Fmt 8091 Sfmt 8091 Y:\SGML\232075.XXX 232075 wreier-aviles on DSK5TPTVN1PROD with CFR U.S. GOVERNMENT OFFICIAL EDITION NOTICE Legal Status and Use of Seals and Logos The seal of the National Archives and Records Administration (NARA) authenticates the Code of Federal Regulations (CFR) as the official codification of Federal regulations established under the Federal Register Act. Under the provisions of 44 U.S.C. 1507, the contents of the CFR, a special edition of the Federal Register, shall be judicially noticed. The CFR is prima facie evidence of the origi- nal documents published in the Federal Register (44 U.S.C. 1510). It is prohibited to use NARA’s official seal and the stylized Code of Federal Regulations logo on any republication of this material without the express, written permission of the Archivist of the United States or the Archivist’s designee. Any person using NARA’s official seals and logos in a manner inconsistent with the provisions of 36 CFR part 1200 is subject to the penalties specified in 18 U.S.C. 506, 701, and 1017. Use of ISBN Prefix This is the Official U.S. Government edition of this publication and is herein identified to certify its authenticity. -

Inventory and Analysis of Archaeological Site Occurrence on the Atlantic Outer Continental Shelf

OCS Study BOEM 2012-008 Inventory and Analysis of Archaeological Site Occurrence on the Atlantic Outer Continental Shelf U.S. Department of the Interior Bureau of Ocean Energy Management Gulf of Mexico OCS Region OCS Study BOEM 2012-008 Inventory and Analysis of Archaeological Site Occurrence on the Atlantic Outer Continental Shelf Author TRC Environmental Corporation Prepared under BOEM Contract M08PD00024 by TRC Environmental Corporation 4155 Shackleford Road Suite 225 Norcross, Georgia 30093 Published by U.S. Department of the Interior Bureau of Ocean Energy Management New Orleans Gulf of Mexico OCS Region May 2012 DISCLAIMER This report was prepared under contract between the Bureau of Ocean Energy Management (BOEM) and TRC Environmental Corporation. This report has been technically reviewed by BOEM, and it has been approved for publication. Approval does not signify that the contents necessarily reflect the views and policies of BOEM, nor does mention of trade names or commercial products constitute endoresements or recommendation for use. It is, however, exempt from review and compliance with BOEM editorial standards. REPORT AVAILABILITY This report is available only in compact disc format from the Bureau of Ocean Energy Management, Gulf of Mexico OCS Region, at a charge of $15.00, by referencing OCS Study BOEM 2012-008. The report may be downloaded from the BOEM website through the Environmental Studies Program Information System (ESPIS). You will be able to obtain this report also from the National Technical Information Service in the near future. Here are the addresses. You may also inspect copies at selected Federal Depository Libraries. U.S. Department of the Interior U.S. -

CSS Georgia 2007 New South Assoc Rpt.Pdf

I J K L New South Assciates • 6150 East Ponce de Leon Avenue • Stone Mountain, Georgia 30083 CSS Georgia: Archival Study CONTRACT NO. DACW21-99-D-0004 DELIVERY ORDER 0029 Report submitted to: U.S. Army Corps of Engineers Savannah District 100 West Oglethorpe Avenue Savannah, Georgia 31402-0889 Report submitted by: New South Associates 6150 East Ponce de Leon Avenue Stone Mountain, Georgia 30083 _____________________________________ Mary Beth Reed - Principal Investigator Authors: Mark Swanson, New South Associates – Historian and Robert Holcombe, National Civil War Naval Museum – Historian New South Associates Technical Report 1092 January 31, 2007 CSS GEORGIA iii ARCHIVAL STUDY Table of Contents Introduction 1 Part One: Historical Context 3 The Setting: Geography of the Savannah Area 3 Pre-War Economic Developments, 1810-1860 5 Changes in Warfare, 1810-1860 6 Initial Development of Confederate Navy, 1861 – March 1862 8 Confederate Navy Reorganization, 1862-1863 17 Josiah Tattnall and the Beginnings of the Savannah Squadron, Early 1861 20 War Comes to Savannah, November 1861 – April 1862 23 Impetus for Georgia: The Ladies Gunboat Association 28 Construction of Georgia, March – October 1862 32 The Placement of Georgia, Late 1862 34 The Savannah Station and Squadron, 1862-1864 36 Fall of Savannah, December 1864 39 Part Two: CSS Georgia - Research Themes 41 Planning and Construction 41 1. Individuals and Organizations Involved in Fund-Raising 41 2. Evidence for Conception of Construction Plans for the Vessel; Background and Skill of Those Involved and an Estimate of How Long They Worked on the Project 45 3. Evidence for the Location of the Construction Site, the Site Where the Engine and Machinery Were Installed, and a Description of These Facilities 48 4. -

Independent Republic Quarterly, 2010, Vol. 44, No. 1-2 Horry County Historical Society

Coastal Carolina University CCU Digital Commons The ndeI pendent Republic Quarterly Horry County Archives Center 2010 Independent Republic Quarterly, 2010, Vol. 44, No. 1-2 Horry County Historical Society Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.coastal.edu/irq Part of the Civic and Community Engagement Commons, and the History Commons Recommended Citation Horry County Historical Society, "Independent Republic Quarterly, 2010, Vol. 44, No. 1-2" (2010). The Independent Republic Quarterly. 151. https://digitalcommons.coastal.edu/irq/151 This Journal is brought to you for free and open access by the Horry County Archives Center at CCU Digital Commons. It has been accepted for inclusion in The ndeI pendent Republic Quarterly by an authorized administrator of CCU Digital Commons. For more information, please contact [email protected]. The Independent Republic Quarterly A Publication of the Horry County Historical Society Volume 44, No. 1-2 ISSN 0046-8843 Publication Date 2010 (Printed 2012) Calendar Events: A Timeline for Civil War-Related Quarterly Meeting on Sunday, July 8, 2012 at Events from Georgetown to 3:00 p.m. Adam Emrick reports on Little River cemetery census pro- ject using ground pen- etrating radar. By Rick Simmons Quarterly Meeting on Used with permission: taken from Defending South Carolina’s Sunday, October 14, 2012 at 3:00 p.m. Au- Coast: The Civil War from Georgetown to Little River (Charleston, thors William P. Bald- SC: The History Press 2009) 155-175. win and Selden B. Hill [Additional information is added in brackets.] review their book The Unpainted South: Car- olina’s Vanishing World. -

Rare Anti Semitic Children's Book with 3 Page

Helen & Marc Younger Pg 47 [email protected] RARE ANTI SEMITIC CHILDREN’S BOOK WITH 3 PAGE HANDWRITTEN LETTER FROM JOB 267. JEWISH INTEREST. (ANTI-SEMITISM) DAS LIED VOM LEVI [THE 269. (JOB)illus. L’EPOPEE DU COSTUME MILITAIRE FRANCAIS by Henri SONG OF LEVI] by Eduard Schwechten. Dusseldorf: J. Knippenberg (1933). 8vo Bouchot. Paris: Societe Francaise D’Editions D’art / L. Henry May, [1898]. (5 1/8 x 7 3/4”), wraps, VG+. First published in 1895, this is the first edition of Thick 4to (10 ½ x 13”), original handsome binding of full embossed leather with the Nazi era edition with the addition of a 2 page essay on the author by Hermann gold and red designs, all edges gilt, Fine. 1st edition. The text is a detailed Bartmann. The text is an anti-Semitic story in verse for children. It features all history of French military campaigns and costumes with emphasis on Napoleon of the nearly 50 disgusting full and partial page anti Semitic illustrations of the and the Grand Imperial Army. Illustrated by JOB with 10 color plates plus 175 first edition, by Siegfried Horn. In this edition the illustrations were printed in exquisitely detailed engraved illustrations on nearly every page of text, many gravure which really accentuated the details in the images. $850.00 of which are hand-colored. Printed on coated paper and a beautiful book. Laid-in is a THREE PAGE HANDWRITTEN LETTER FROM JOB regarding the publication of one of his books. It reads: “My editor, M. Combet forwarded your letter to me - as for the table of contents, it will be delivered this month as well as the cover. -

Year Book of the Holland Society of New-York

w r 974.7 PUBLIC LIBRARY M. L, H71 FORT WAYNE & ALLEM CO., IND. 1916 472087 SENE^AUOGV C0L.L-ECT!0N EN COUNTY PUBLIC lllllilllllilll 3 1833 01147 7442 TE^R BOOK OF The Holland Society OF New Tork igi6 PREPARED BY THE RECORDING SECRETARY Executive Office 90 West Street new york city Copyright 1916 The Holland Society of New York : CONTENTS DOMINE SELYNS' RECORDS: PAGE Introduction I Table of Contents 2 Discussion of Previous Editions 10 Text 21 Appendixes 41 Index 81 ADMINISTRATION Constitution 105 By-Laws 112 Badges 116 Accessions to Library 123 MEMBERSHIP: 472087 Former Officers 127 Committees 1915-16 142 List of Members 14+ Necrology 172 MEETINGS: Anniversary of Installation of First Mayor and Board of Aldermen 186 Poughkeepsie 199 Smoker 202 Hudson County Branch 204 Banquet 206 Annual Meeting 254 New Officers, 1916 265 In Memoriam 288 ILLUSTRATIONS PAGE Gerard Beekman—Portrait Frontispiece New York— 1695—Heading Cut i Selyns' Seal— Initial Letter i Dr. James S. Kittell— Portrait 38 North Church—Historic Plate 43 Map of New York City— 1695 85 Hon. Francis J. Swayze— Portrait 104 Badge of the Society 116 Button of the Society 122 Hon. William G. Raines—Portrait 128 Baltus Van Kleek Homestead—Heading Cut. ... 199 Eagle Tavern at Bergen—Heading Cut 204 Banquet Layout 207 Banquet Ticket 212 Banquet Menu 213 Ransoming Dutch Captives 213 New Amsterdam Seal— 1654 216 New York City Seal— 1669 216 President Wilson Paying Court to Father Knick- erbocker 253 e^ c^^ ^ 79c^t'*^ C»€^ THE HOLLAND SOCIETY TABLE OF CONTENTS. Introduction. Description and History of the Manuscript Volume.