Eskimo Languages in Asia, 1791 On, and the Wrangel Island-Point Hope Connection"

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Beaufort Sea: Hypothetical Very Large Oil Spill and Gas Release

OCS Report BOEM 2020-001 BEAUFORT SEA: HYPOTHETICAL VERY LARGE OIL SPILL AND GAS RELEASE U.S. Department of the Interior Bureau of Ocean Energy Management Alaska OCS Region OCS Study BOEM 2020-001 BEAUFORT SEA: HYPOTHETICAL VERY LARGE OIL SPILL AND GAS RELEASE January 2020 Author: Bureau of Ocean Energy Management Alaska OCS Region U.S. Department of the Interior Bureau of Ocean Energy Management Alaska OCS Region REPORT AVAILABILITY To download a PDF file of this report, go to the U.S. Department of the Interior, Bureau of Ocean Energy Management (www.boem.gov/newsroom/library/alaska-scientific-and-technical-publications, and click on 2020). CITATION BOEM, 2020. Beaufort Sea: Hypothetical Very Large Oil Spill and Gas Release. OCS Report BOEM 2020-001 Anchorage, AK: U.S. Department of the Interior, Bureau of Ocean Energy Management, Alaska OCS Region. 151 pp. Beaufort Sea: Hypothetical Very Large Oil Spill and Gas Release BOEM Contents List of Abbreviations and Acronyms ............................................................................................................. vii 1 Introduction ........................................................................................................................................... 1 1.1 What is a VLOS? ......................................................................................................................... 1 1.2 What Could Precipitate a VLOS? ................................................................................................ 1 1.2.1 Historical OCS and Worldwide -

Siberian Coast & Polar Bears of Wrangel Island, Russia

Siberian Coast & Polar Bears of Wrangel Island, Russia Aboard the Spirit of Enderby July 24–August 6, 2013 Tuesday / Wednesday July 23 / July 24 – Anadyr, Russia Arrival Over several days, North American trip participants slowly began to arrive in Nome, Alaska for our charter flights to Anadyr, Russia. Participants from other parts of the world made their way to Anadyr through Moscow. Altogether, passengers included passport holders from 11 countries. Many people had flown into Nome several days early, rented cars, and driven the local roads in search of accessible musk oxen in the meadows near town, Pacific and red-throated loons in small tundra ponds, and gulls, ducks and shorebirds along the coast. On July 23, most of our group consolidated their luggage in our Nome hotel lobby and had it loaded on a truck to be taken to our charter airline hangar, while we followed in a bus with our camera gear. Thick fog was drifting along the coast and, when we reached the hanger, we were informed the Nome Airport was closed to inbound air traffic. That posed no real problem for us because our small airplanes were already at the hangar in Nome, on stand-by and readily available, and, since the fog was intermittent, it seemed certain we would have almost no problem departing to Russia. A breakfast buffet was arranged in the hangar and we were regaled by local Nome personality Richard Beneville—who also organized our land-based transportation—with his tales of moving to Nome following his life as a theater actor in New York City and anecdotes of his decades-long life in hardscrabble Nome. -

The Polar Bear of the Arctic Coast of Chukotka Download: 1 Mb | *.PDF

CONTENT INTRODUCTION...........................................................................................................................2 1. Objectives....................................................................................................................................2 2. The area of observations .............................................................................................................2 3. Information collection regimes ...................................................................................................4 3.1. Regular stationary observations ...........................................................................................4 3.1. Regular on-the-route observations .......................................................................................4 3.3. Non-regular stationary observations ....................................................................................4 3.4. Incidental cocurrent observations ........................................................................................5 4. Methods of conducting observations ..........................................................................................5 4.1. The order of conducting stationary observations (regular, non-regular and one-time). ......5 4.1.1. General information on observation.............................................................................5 4.1.2. Observations of animals................................................................................................6 4.2. -

Research on Polar Bear Autumn Aggregations on Chukotka, 1989–2004

Polar Bears: Proceedings of the Fourteenth Working Meeting Polar Bears: Proceedings of the Fourteenth Working Polar Bears Proceedings of the 14th Working Meeting of the IUCN/SSC Polar Bear Specialist Group, 20–24 June 2005, Seattle, Washington, USA Compiled and edited by Jon Aars, Nicholas J. Lunn and Andrew E. Derocher Rue Mauverney 28 1196 Gland Switzerland Tel +41 22 999 0000 Fax +41 22 999 0002 [email protected] Occasional Paper of the IUCN Species Survival Commission No. 32 www.iucn.org World Headquarters IUCN Research on polar bear autumn aggregations on Chukotka, 1989–2004 A.A. Kochnev, Pacific Research Fisheries Center (TINRO), Chukotka Branch, Box 29, Otke 56, 689000, Anadyr, Russian Federation This report includes results of investigations on polar Somnitel’naya Spit (Figure 27). Polar bears were observed bear aggregations that formed on islands and the from a 12m high navigation watchtower close to the areas continental coast in the western part of the Chukchi Sea with the highest density of bears. From August to early during autumn. Fieldwork was conducted on Wrangel October, surveys were conducted two times a day (in the and Herald islands in 1989–98 and on the arctic morning and in the evening). As the day length shortened continental coast of Chukotka in 2002–04 (Figure 26). (usually after October 10), polar bears were observed Data were collected from a motor boat and by direct once per day. Binoculars (12x40) were used to count all observation in key areas inhabited by bears. Some animals. Field of view varied with weather conditions additional information was obtained from the archives of reaching a maximum of 6km under ideal conditions. -

Across the Top of the World

EXPEDITION DOSSIER 22ND JULY – 5TH AUGUST 2019 ACROSS THE TOP OF THE WORLD TO WRANGEL AND HERALD ISLANDS © J Ross TO WRANGEL AND ACROSS THE TOP OF THE WORLD HERALD ISLANDS This unique expedition crosses the Arctic Circle and includes the isolated and pristine Wrangel and Herald Islands and a significant section of the wild North Eastern Siberian coastline. It is a journey only made possible in recent years by the thawing in the politics of the region and the retreat of summer pack ice in the Chukchi Sea. The very small distance between Russia and the USA along this border area was known as the Ice Curtain, behind which then and now lies one of the last great undiscovered wilderness areas in the world. The voyage journeys through the narrow Bering Strait, which separates Russia from the United States of America, and then travels west along the Chukotka coastline before crossing the De Long Strait to Wrangel Island. There we will spend four to five days under the guidance of local rangers on the nature reserve. Untouched by glaciers during the last ice age, this island is a treasure trove of Arctic biodiversity and is perhaps best known for the multitude of Polar Bears that breed here. We hope to catch many glimpses of this beautiful animal. The island also boasts the world’s largest population of Pacific Walrus and lies near major feeding grounds for the Gray Whales that migrate thousands of kilometres north from their breeding grounds in Baja, Mexico. Reindeer, Musk Ox and Snow Geese can normally be seen further inland. -

Wetlands in Russia

WETLANDS IN RUSSIA Volume 4 Wetlands in Northeastern Russia Compiled by A.V.Andreev Moscow 2004 © Wetlands International, 2004 All rights reserved. Apart from any fair dealing for the purpose of private study, research, criticism, or review (as permitted under the Copyright Designs and Patents Act 1988) no part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic, electrical, chemical, mechanical, optical, photocopying, recording or otherwise, without prior permission of the copyright holder. The production of this publication has been generously supported by the Ministry of Agriculture, Nature and Food Quality, The Netherlands Citation: Andreev, A.V. 2004. Wetlands in Russia, Volume 4: Wetlands in Northeastern Russia. Wetlands International–Russia Programme.198 pp. ISBN 90-5882-024-6 Editorial Board: V.O.Avdanin, V.G.Vinogradov, V.Yu. Iliashenko, I.E.Kamennova, V.G.Krivenko, V.A.Orlov, V.S.Ostapenko, V.E.Flint Translation: Yu.V.Morozov Editing of English text: D. Engelbrecht Layout: M.A.Kiryushkin Cover photograph: A.V.Andreev Designed and produced by KMK Scientific Press Available from: Wetlands International-Russia Programme Nikoloyamskaya Ulitsa, 19, stroeniye 3 Moscow 109240, Russia Fax: + 7 095 7270938; E-mail: [email protected] The presentation of material in this publication and the geographical designations employed do not imply the expression of any opinion whatsoever on the part of Wetlands International, concerning the legal status of any territory or area, -

Chronology of the Key Historical Events on the Eastern Seas of the Russian Arctic (The Laptev Sea, the East Siberian Sea, the Chukchi Sea)

Chronology of the Key Historical Events on the Eastern Seas of the Russian Arctic (the Laptev Sea, the East Siberian Sea, the Chukchi Sea) Seventeenth century 1629 At the Yenisei Voivodes’ House “The Inventory of the Lena, the Great River” was compiled and it reads that “the Lena River flows into the sea with its mouth.” 1633 The armed forces of Yenisei Cossacks, headed by Postnik, Ivanov, Gubar, and M. Stadukhin, arrived at the lower reaches of the Lena River. The Tobolsk Cossack, Ivan Rebrov, was the first to reach the mouth of Lena, departing from Yakutsk. He discovered the Olenekskiy Zaliv. 1638 The first Russian march toward the Pacific Ocean from the upper reaches of the Aldan River with the departure from the Butalskiy stockade fort was headed by Ivan Yuriev Moskvitin, a Cossack from Tomsk. Ivan Rebrov discovered the Yana Bay. He Departed from the Yana River, reached the Indigirka River by sea, and built two stockade forts there. 1641 The Cossack foreman, Mikhail Stadukhin, was sent to the Kolyma River. 1642 The Krasnoyarsk Cossack, Ivan Erastov, went down the Indigirka River up to its mouth and by sea reached the mouth of the Alazeya River, being the first one at this river and the first one to deliver the information about the Chukchi. 1643 Cossacks F. Chukichev, T. Alekseev, I. Erastov, and others accomplished the sea crossing from the mouth of the Alazeya River to the Lena. M. Stadukhin and D. Yarila (Zyryan) arrived at the Kolyma River and founded the Nizhnekolymskiy stockade fort on its bank. -

University Microfilms International 300 N

The Breeding Biology Of The Puffins: Tufted Puffin (Lunda Cirrhata), Horned Puffin (Fratercula Corniculata), Common Puffin (F. Arctica), And Rhinoceros Auklet (Cerorhinca Monocerata) Item Type Thesis Authors Wehle, Duff Henry Strong Download date 09/10/2021 09:57:35 Link to Item http://hdl.handle.net/11122/9312 INFORMATION TO USERS This was produced from a copy of a document sent to us for microfilming. While the most advanced technological means to photograph and reproduce this document have been used, the quality is heavily dependent upon the quality of the material subm itted. The following explanation of techniques is provided to help you understand markings or notations which may appear on this reproduction. 1. Trie sign or “ target” fo r pages apparently lacking from the docum ent photographed is “Missing Page(s)”. If it was possible to obtain the missing page(s) or section, they are spliced into the film along with adjacent pages. This may have necessitated cutting through an image and duplicating adjacent pages to assure you of complete continuity. 2. When an image on the film is obliterated with a round black mark it is an indication that the film inspector noticed either blurred copy because of movement during exposure, or duplicate copy. Unless we meant to delete copyrighted materials that should not have been filmed, you will find a good image of the page in the adjacent frame. If copyrighted materials were deleted you will find a target note listing the pages in the adjacent frame. 3. When a map, drawing or chart, etc., is part of the material being photo graphed the photographer has followed a definite method in “sectioning” the material. -

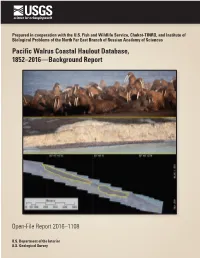

Pacific Walrus Coastal Haulout Database, 1852–2016—Background Report

Prepared in cooperation with the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service, Chukot-TINRO, and Institute of Biological Problems of the North Far East Branch of Russian Academy of Sciences Pacific Walrus Coastal Haulout Database, 1852–2016—Background Report Open-File Report 2016–1108 U.S. Department of the Interior U.S. Geological Survey Cover: Images of walrus haulouts. A ground level view of an autumn haulout with adult females and young (Point Lay, Alaska, September, 25, 2013) is shown in the top panel. An aerial composite image of a large haulout with more than 1,000 male walruses is shown in the middle panel (Cape Greig, Alaska, May 3, 2016). A composite image of a very large haulout with tens of thousands of adult female walruses and their young is shown in the bottom panel in which the outlines of the haulout is highlighted in yellow (Point Lay, Alaska, August 26, 2011). Photo credits (top panel: Ryan Kingsbery, USGS; middle panel: Sarah Schoen, USGS; bottom panel: USGS). Pacific Walrus Coastal Haulout Database, 1852–2016—Background Report By Anthony S. Fischbach, Anatoly A. Kochnev, Joel L. Garlich-Miller, and Chadwick V. Jay Prepared in cooperation with the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service and Chukot-TINRO and Institute of Biological Problems of the North Far East Branch of Russian Academy of Sciences Open-File Report 2016–1108 U.S. Department of the Interior U.S. Geological Survey U.S. Department of the Interior SALLY JEWELL, Secretary U.S. Geological Survey Suzette M. Kimball, Director U.S. Geological Survey, Reston, Virginia: 2016 For more information on the USGS—the Federal source for science about the Earth, its natural and living resources, natural hazards, and the environment—visit http://www.usgs.gov/ or call 1–888–ASK–USGS (1–888–275–8747). -

Arktis Eisbrecher-Expeditionen IB KAPITAN KHLEBNIKOV

Arktis Eisbrecher-Expeditionen IB KAPITAN KHLEBNIKOV POLARADVENTURES Schiffs- und Flug-Expeditionen in Arktis und Antarktis Reiseagentur * Heinrich-Böll-Str. 40 * D-21335 Lüneburg * Deutschland Tel +49-4131- 223474 Fax +49-4131-54255 [email protected] www.polaradventures.de Saison 201 9 Reederei Direkt-Angebote ab-bis Hafen für individuelle Planungen alle Abfahrten der Saison inkl. englischsprachiger Termine POLARADVENTURES Schiffs- und Flug-Expeditionen in Arktis und Antarktis Reiseagentur * Heinrich-Böll-Str. 40 * D-21335 Lüneburg * Deutschland Tel +49-4131- 223474 Fax +49-4131-54255 [email protected] www.polaradventures.de IN DETAIL • Expedition Staff & Crew: 70 INTRODUCING • Guests: 110 KAPITAN KHLEBNIKOV • Length: 122.5m Last year we promised exciting projects were afoot at Heritage • Beam: 26.5m Expeditions, and we are exceptionally excited and proud to announce • Draft: 8.5m we will be operating world-renowned Soviet icebreaker and former research vessel Kapitan Khlebnikov for our Wrangel Island expeditions. • Gross Tonnage: 12,288gt The addition of Kapitan Khlebnikov to Heritage Expeditions’ fleet enables • Engine: 24,000 horsepower us to provide an unrivalled platform for High Arctic exploration combining • Ice Class: LL3 the exceptional navigation capabilities of Kapitan Khlebnikov with our intrepid expedition programs and experienced team. • Cruising speed: 12/14 knots This peerless, authentic polar-class icebreaker holds the passenger ship • Zodiacs: 10 record for the most crossings of the Northwest Passage and has famously circumnavigated Antarctica – twice. Built in 1981 by Finland’s Wärtsilä Company and one of four Kapitan Sorokin-class icebreakers, Kapitan ONBOARD FACILITIES Khlebnikov wraps comfortable surrounds in a formidable, ice-reinforced vessel capable of breaking ice as thick as two metres. -

MELTDOWN! a Symposium on Global Warming Circumnavigation of Wrangel Island Aboard the Icebreaker Kapitan Khlebnikov July

MELTDOWN! A Symposium on Global Warming Circumnavigation of Wrangel Island aboard the Icebreaker Kapitan Khlebnikov July 5–18, 2007 DETAILED PRELIMINARY ITINERARY (subject to amendment) HOME/ANCHORAGE, ALASKA Thursday, July 5 Fly from home to Anchorage, Alaska, and transfer independently to the Millennium Hotel for our overnight stay. Modern, bustling Anchorage offers quick access to the state’s vast wilderness of mountains, glaciers and forests. MILLENNIUM HOTEL (no meals) ANCHORAGE / ANADYR, RUSSIA Friday & Saturday, July 6 & 7 We take a morning flight from Anchorage to Anadyr, capital of Chukotka province, “losing” a day as we travel west across the International Date Line. After officially entering Russia (crossing frontiers can be an adventure in itself), you then transfer by helicopter to the Kapitan Khlebnikov waiting offshore. KAPITAN KHLEBNIKOV CHUKOTKA PENINSULA Sunday & Monday, July 8 & 9 Onboard presentations get under way with an introduction to the wildlife, geology, glaciology and history of Russia’s Far North. Your shore adventures begin on the remote, rugged Chukotka Peninsula, a naturalist’s paradise where high-latitude plants such as Arctic poppies and saxifrages are in flower. Explore the coast and nearby islands, home to myriad nesting seabirds, including Least Auklets, Crested Auklets, Tufted Puffins, Horned Puffins, guillemots. At ancient cultural sites, you can examine ceremonial grounds, learning about the early inhabitants of the Russian Arctic. We’re also hoping to explore Whalebone Alley, a sacred place for early native whalers on Ittygran Island, where you can wander among the 500-year-old skeletons of giant bowhead whales. KAPITAN BERING STRAIT & CAPE DEZHNEV Tuesday, July 10 We sail through the famed Bering Strait, the relatively narrow waterway separating Russia from the United States, with the island of Big Diomede, Russia’s furthest outpost, off our starboard bow. -

Wrangel Island in the Russian High Arctic with Mark Carwardine

Wrangel Island in the Russian High Arctic with Mark Carwardine A very special expedition, with outstanding photographic opportunities, to one of the least explored wildernesses on Earth. 25 July – 8 August 2022 About our trip lifetime journey is made possible only by the retreat of the pack ice in summer. This 14-night expedition cruise, on the Spirit of Enderby Wrangel boasts an astonishing abundance of wildlife. The (which is also known as Akademik Shokalskiy), travels island hosts the largest polar bear denning ground in the along the Chukotka Peninsula, sails through the Bering world and is home to Pacific walruses, wolverines, Strait (which separates Russia from the United States), muskoxen, reindeer, snowy owls, snow geese, king eiders, crosses the Arctic Circle, continues west along the wild ivory, Ross’s and Sabine’s gulls, vast seabird colonies, and coastline of northeastern Siberia, and then pushes much, much more. We will enjoy lots of Zodiac cruises, and 140km further north to one of the most remote wildlife plenty of landings, and will be watching for all sorts of hotspots in the world: Wrangel Island. This once-in-a- wildlife from the ship. The surrounding seas are great for whale watching: humpback, fin and bowhead whales, orcas and belugas all occur here, as well as grey whales, which migrate all the way from their winter breeding lagoons along the coast of Baja California, Mexico, to feed. Add mammoth tusks (Wrangel is believed to be the last place on Earth where woolly mammoths lived and their curved tusks are literally everywhere), hundreds of plant species, phenomenal geological formations, and you can begin to understand why this High Arctic island is so special.