Can We Observe X Tonight?

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Observer's Handbook for 1912

T he O bservers H andbook FOR 1912 PUBLISHED BY THE ROYAL ASTRONOMICAL SOCIETY OF CANADA E d i t e d b y C. A, CHANT FOURTH YEAR OF PUBLICATION TORONTO 198 C o l l e g e St r e e t Pr in t e d fo r t h e So c ie t y 1912 T he Observers Handbook for 1912 PUBLISHED BY THE ROYAL ASTRONOMICAL SOCIETY OF CANADA TORONTO 198 C o l l e g e St r e e t Pr in t e d fo r t h e S o c ie t y 1912 PREFACE Some changes have been made in the Handbook this year which, it is believed, will commend themselves to observers. In previous issues the times of sunrise and sunset have been given for a small number of selected places in the standard time of each place. On account of the arbitrary correction which must be made to the mean time of any place in order to get its standard time, the tables given for a particualar place are of little use any where else, In order to remedy this the times of sunrise and sunset have been calculated for places on five different latitudes covering the populous part of Canada, (pages 10 to 21), while the way to use these tables at a large number of towns and cities is explained on pages 8 and 9. The other chief change is in the addition of fuller star maps near the end. These are on a large enough scale to locate a star or planet or comet when its right ascension and declination are given. -

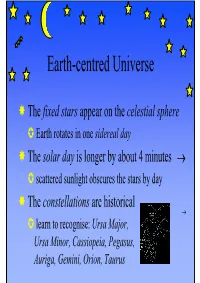

Earth-Centred Universe

Earth-centred Universe The fixed stars appear on the celestial sphere Earth rotates in one sidereal day The solar day is longer by about 4 minutes → scattered sunlight obscures the stars by day The constellations are historical → learn to recognise: Ursa Major, Ursa Minor, Cassiopeia, Pegasus, Auriga, Gemini, Orion, Taurus Sun’s Motion in the Sky The Sun moves West to East against the background of Stars Stars Stars stars Us Us Us Sun Sun Sun z z z Start 1 sidereal day later 1 solar day later Compared to the stars, the Sun takes on average 3 min 56.5 sec extra to go round once The Sun does not travel quite at a constant speed, making the actual length of a solar day vary throughout the year Pleiades Stars near the Sun Sun Above the atmosphere: stars seen near the Sun by the SOHO probe Shield Sun in Taurus Image: Hyades http://sohowww.nascom.nasa.g ov//data/realtime/javagif/gifs/20 070525_0042_c3.gif Constellations Figures courtesy: K & K From The Beauty of the Heavens by C. F. Blunt (1842) The Celestial Sphere The celestial sphere rotates anti-clockwise looking north → Its fixed points are the north celestial pole and the south celestial pole All the stars on the celestial equator are above the Earth’s equator How high in the sky is the pole star? It is as high as your latitude on the Earth Motion of the Sky (animated ) Courtesy: K & K Pole Star above the Horizon To north celestial pole Zenith The latitude of Northern horizon Aberdeen is the angle at 57º the centre of the Earth A Earth shown in the diagram as 57° 57º Equator Centre The pole star is the same angle above the northern horizon as your latitude. -

Trajectory Coordinate System Information We Have Calculated the New Horizons Trajectory and Full State Vector Information in 11 Different Coordinate Systems

Trajectory Coordinate System Information We have calculated the New Horizons trajectory and full state vector information in 11 different coordinate systems. Below we describe the coordinate systems, and in the next section we describe the trajectory file format. Heliographic Inertial (HGI) This system is Sun centered with the X-axis along the intersection line of the ecliptic (zero longitude occurs at the +X-axis) and solar equatorial planes. The Z-axis is perpendicular to the solar equator, and the Y-axis completes the right-handed system. This coordinate system is also referred to as the Heliocentric Inertial (HCI) system. Heliocentric Aries Ecliptic Date (HAE-DATE) This coordinate system is heliocentric system with the Z-axis normal to the ecliptic plane and the X-axis pointes toward the first point of Aries on the Vernal Equinox, and the Y- axis completes the right-handed system. This coordinate system is also referred to as the Solar Ecliptic (SE) coordinate system. The word “Date” refers to the time at which one defines the Vernal Equinox. In this case the date observation is used. Heliocentric Aries Ecliptic J2000 (HAE-J2000) This coordinate system is heliocentric system with the Z-axis normal to the ecliptic plane and the X-axis pointes toward the first point of Aries on the Vernal Equinox, and the Y- axis completes the right-handed system. This coordinate system is also referred to as the Solar Ecliptic (SE) coordinate system. The label “J2000” refers to the time at which one defines the Vernal Equinox. In this case it is defined at the J2000 date, which is January 1, 2000 at noon. -

3.- the Geographic Position of a Celestial Body

Chapter 3 Copyright © 1997-2004 Henning Umland All Rights Reserved Geographic Position and Time Geographic terms In celestial navigation, the earth is regarded as a sphere. Although this is an approximation, the geometry of the sphere is applied successfully, and the errors caused by the flattening of the earth are usually negligible (chapter 9). A circle on the surface of the earth whose plane passes through the center of the earth is called a great circle . Thus, a great circle has the greatest possible diameter of all circles on the surface of the earth. Any circle on the surface of the earth whose plane does not pass through the earth's center is called a small circle . The equator is the only great circle whose plane is perpendicular to the polar axis , the axis of rotation. Further, the equator is the only parallel of latitude being a great circle. Any other parallel of latitude is a small circle whose plane is parallel to the plane of the equator. A meridian is a great circle going through the geographic poles , the points where the polar axis intersects the earth's surface. The upper branch of a meridian is the half from pole to pole passing through a given point, e. g., the observer's position. The lower branch is the opposite half. The Greenwich meridian , the meridian passing through the center of the transit instrument at the Royal Greenwich Observatory , was adopted as the prime meridian at the International Meridian Conference in 1884. Its upper branch is the reference for measuring longitudes (0°...+180° east and 0°...–180° west), its lower branch (180°) is the basis for the International Dateline (Fig. -

Theosophical Siftings the Zodiac Vol 6, No 13 the Zodiac

Theosophical Siftings The Zodiac Vol 6, No 13 The Zodiac by S.G.P. Coryn Reprinted from "Theosophical Siftings" Volume 6 The Theosophical Publishing Society, England [Page 3] OF our nineteenth century researches into the knowledge, the science and the mythology of the ancients, there is probably no department which has given rise to discussion so animated, to speculations so varied, to conclusions often and usually so fallacious, as that of the Zodiac and its twelve signs. Nor need we greatly wonder at the interest which it has evoked. To the sincere student who wishes only for wisdom and understanding, and who does not seek to force and to bend the facts of nature into the mould of his own creed, the Zodiac promises something more than a glimpse into the secrets of the Universe. Almost insensibly to himself he is led to perceive that herein lie the mystic tracings, in divine handwriting, of the world's past and a prophecy of things to come. And on the other side, we find very much the same enthusiasm of research, but directed to the belittling of the history of the Zodiac and to a reduction of its symbology and the mysteries and the myths and the legends which have gathered around it, to the superstition of peoples who knew no written language, nor arts, nor sciences, but believed themselves able to read the signs and the tokens of the heavens above them. And justly may the champions of the creed of a day seek to diminish the importance of the Zodiac, and well may they fear the revelations which it may bring. -

COORDINATES, TIME, and the SKY John Thorstensen

COORDINATES, TIME, AND THE SKY John Thorstensen Department of Physics and Astronomy Dartmouth College, Hanover, NH 03755 This subject is fundamental to anyone who looks at the heavens; it is aesthetically and mathematically beautiful, and rich in history. Yet I'm not aware of any text which treats time and the sky at a level appropriate for the audience I meet in the more technical introductory astronomy course. The treatments I've seen either tend to be very lengthy and quite technical, as in the classic texts on `spherical astronomy', or overly simplified. The aim of this brief monograph is to explain these topics in a manner which takes advantage of the mathematics accessible to a college freshman with a good background in science and math. This math, with a few well-chosen extensions, makes it possible to discuss these topics with a good degree of precision and rigor. Students at this level who study this text carefully, work examples, and think about the issues involved can expect to master the subject at a useful level. While the mathematics used here are not particularly advanced, I caution that the geometry is not always trivial to visualize, and the definitions do require some careful thought even for more advanced students. Coordinate Systems for Direction Think for the moment of the problem of describing the direction of a star in the sky. Any star is so far away that, no matter where on earth you view it from, it appears to be in almost exactly the same direction. This is not necessarily the case for an object in the solar system; the moon, for instance, is only 60 earth radii away, so its direction can vary by more than a degree as seen from different points on earth. -

The Succession of World Ages Jane B

The Succession of World Ages Jane B. Sellers From The Death of Gods in Ancient Egypt © 1992, 2007 by Jane Sellers aking up the challenge laid been the product of a long development, for down in Hamlet’s Mill to find it is not until the fourth century bc that we Tarchaeoastronomical origins for find the first use of signs for these segments. many of humanity’s myths, Jane Sellers But certainly by 700 bc, in a Babylonian text undertook to discover the correlations between known as MUL.APIN the path of the sun was the astronomical knowledge of the ancient divided into 4 parts with the sun spending Egyptians and their mythic structures. In this three months in each. Since the months were selection, she discusses the precession of the usually reckoned to have 30 days, it easily equinoxes, vital to the understanding of the followed that the monthly segments of the Mithraic Mysteries. Hipparchus may have zodiac would be each assigned 30 “degrees.” rediscovered this astronomical phenomenon, Antiquity of the Zodiac however, it is clear that the Egyptians were Many astronomers harbor a belief that aware of it centuries before. the division of the sun’s path into twelve At the moment of the Spring equal segments far predated this text. Equinox the heavens are never in Charles A. Whitney, Professor of Astronomy quite the same position they were at Harvard, in Whitney’s Starfinder, 1986– in the year before, since there is a 89 writes, “Three thousand years ago and very slight annual lag of about 50 perhaps longer—astronomers chose the seconds, which in the course of sun signs according to the corresponding 72 years amounts to 1 degree (50 zodiacal constellations, and they set Aries at seconds x 72 years = 3,600 seconds the spring equinox.”2 = 60 minutes = 1 degree) and in 2,160 years amounts to 30 degrees, which is one “sign” of the zodiac. -

![Sample Quiz Questions on CONSTELLATIONS and STAR MAPS [Quiz 1] for Some of These, You Will Need a Star Map 1](https://docslib.b-cdn.net/cover/2409/sample-quiz-questions-on-constellations-and-star-maps-quiz-1-for-some-of-these-you-will-need-a-star-map-1-3012409.webp)

Sample Quiz Questions on CONSTELLATIONS and STAR MAPS [Quiz 1] for Some of These, You Will Need a Star Map 1

Dr. W. Pezzaglia Astronomy 10A (sec 1), Summer 2017 Page 4 Foothill College Syllabus, Lec #1 (Star Maps, Ecliptic) 2017Jul03 Sample Quiz Questions On CONSTELLATIONS and STAR MAPS [Quiz 1] For some of these, you will need a star map 1. What is the faintest magnitude the eye can see (under ideal circumstances? 2. Who first came up with 60 seconds to the minute and 60 minutes to the hour? 3. Which was not one of the first 4 constellations mapped by the ancients? A. Taurus B. Scorpio C. Aquarius D. Leo E. Orion 4. Which constellation is NOT part of the “Orion Story”? A. Canis Major B. Scorpio C. Sagittarius D. Lepus E. Ophiuchus F. All are 5. How many constellations are there? 6. The third brightest star in the constellation Orion would most likely be called? A. Orion C B. 3-Orionis C. -Orionis D. ceti Orionis E. none of these 7. Who first came up with 360 degrees to the circle? 8. The name for celestial latitude on a star map is: A. right ascension B. hour angle C. declination D. elongation E. none of these 9. One hour of right ascension is equivalent to how many degrees (at the equator)? 10. Which is the Right Ascension of the South Celestial Pole? 11. The star ARCTURUS (In Bootes) has what declination? Right Ascension? Magnitude? 12. The approximate magnitude of the star Megrez (Ursa Major) A. 1 B. 2 C. 3 D. 4 E. none of these 13. Gamma Lyrae probably means the ______ constellation Lyra. A. third brightest star in B. -

Astronomy.Pdf

Astronomy Introduction This topic explores the key concepts of astronomy as they relate to: • the celestial coordinate system • the appearance of the sky • the calendar and time • the solar system and beyond • space exploration • gravity and flight. Key concepts of astronomy The activities in this topic are designed to explore the following key concepts: Earth • Earth is spherical. • ‘Down’ refers to the centre of Earth (in relation to gravity). Day and night • Light comes from the Sun. • Day and night are caused by Earth turning on its axis. (Note that ‘day’ can refer to a 24-hour time period or the period of daylight; the reference being used should be made explicit to students.) • At any one time half of Earth’s shape is in sunlight (day) and half in darkness (night). The changing year • Earth revolves around the Sun every year. • Earth’s axis is tilted 23.5° from the perpendicular to the plane of the orbit of Earth around the Sun; Earth’s tilt is always in the same direction. • As Earth revolves around the Sun, its orientation in relation to the Sun changes because of its tilt. • The seasons are caused by the changing angle of the Sun’s rays on Earth’s surface at different times during the year (due to Earth revolving around the Sun). © Deakin University 1 2 SCIENCE CONCEPTS: YEARS 5–10 ASTRONOMY © Deakin University Earth, the Moon and the Sun • Earth, the Moon and the Sun are part of the solar system, with the Sun at the centre. • Earth orbits the Sun once every year. -

Investigating the Celestial Sphere Objectives

Investigating the Celestial Sphere Objectives • Understand the following Astronomical terms; 1. Right Ascension 2. Declination 3. Hour Angle 4. Azimuth 5. Altitude 6. Solar Time 7. Sidereal Time The Celestial Sphere • In astronomy and navigation, the celestial sphere is an imaginary sphere of arbitrarily large radius, concentric with Earth. All objects in the observer's sky can be thought of as projected upon the inside surface of the celestial sphere, as if it were the underside of a dome or a hemispherical screen. The celestial sphere is a practical tool for spherical astronomy, allowing observers to plot positions of objects in the sky when their distances are unknown or unimportant. Latitude & Longitude For the purpose of positioning and navigation, the earth is divided, horizontally and vertically into lines of latitude and longitude respectfully. Latitude is given in degrees, either decimal or DMS north or south of the equator. So here in Bury St Edmunds we are around 52° N or 52 degrees above the equator. Sydney Australia is 33.8° S or 33.8 degrees below the equator. Longitude can be given in degrees or hours and is the great circle that goes through both poles and your location. It is given in degrees west or east of the prime meridian. The prime meridian 0° was set to run through Greenwich London by political agreement in 1884. essentially it is an arbitrary starting point for measurements in longitude. As the earth rotates 360° in 24 solar hours we can also define a new unit of hours. Each hour is equal to 360/24 or 15°. -

Positional Astronomy : Earth Orbit Around Sun

www.myreaders.info www.myreaders.info Return to Website POSITIONAL ASTRONOMY : EARTH ORBIT AROUND SUN RC Chakraborty (Retd), Former Director, DRDO, Delhi & Visiting Professor, JUET, Guna, www.myreaders.info, [email protected], www.myreaders.info/html/orbital_mechanics.html, Revised Dec. 16, 2015 (This is Sec. 2, pp 33 - 56, of Orbital Mechanics - Model & Simulation Software (OM-MSS), Sec 1 to 10, pp 1 - 402.) OM-MSS Page 33 OM-MSS Section - 2 -------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------13 www.myreaders.info POSITIONAL ASTRONOMY : EARTH ORBIT AROUND SUN, ASTRONOMICAL EVENTS ANOMALIES, EQUINOXES, SOLSTICES, YEARS & SEASONS. Look at the Preliminaries about 'Positional Astronomy', before moving to the predictions of astronomical events. Definition : Positional Astronomy is measurement of Position and Motion of objects on celestial sphere seen at a particular time and location on Earth. Positional Astronomy, also called Spherical Astronomy, is a System of Coordinates. The Earth is our base from which we look into space. Earth orbits around Sun, counterclockwise, in an elliptical orbit once in every 365.26 days. Earth also spins in a counterclockwise direction on its axis once every day. This accounts for Sun, rise in East and set in West. Term 'Earth Rotation' refers to the spinning of planet earth on its axis. Term 'Earth Revolution' refers to orbital motion of the Earth around the Sun. Earth axis is tilted about 23.45 deg, with respect to the plane of its orbit, gives four seasons as Spring, Summer, Autumn and Winter. Moon and artificial Satellites also orbits around Earth, counterclockwise, in the same way as earth orbits around sun. Earth's Coordinate System : One way to describe a location on earth is Latitude & Longitude, which is fixed on the earth's surface. -

The Star Zodiac of Antiquity

The Star Zodiac of Antiquity Nick Kollerstrom In the early third century AD, two zodiac systems converged. 1 One was the ancient star-zodiac derived from the constellations, while the other was the tropical zodiac, with its beginning at 0 0 Aries firmly anchored to the Vernal Point, the Sun’s position at the Spring Equinox. It will be argued here that this latter, tropical, system had not, in the third century, come to be accepted by astrologers, but that it was to gradually come into use amongst astrologers as the earlier, sidereal system sank into a deep oblivion, at least in the West, from which it did not re-emerge until rediscovered late in the nineteenth century. It remains far from easy to ascertain which were the primary reference stars which defined the sidereal zodiac’s position, and there may have been different views on this, amongst the several cultures that adopted it. 2 The term ‘sidereal’ derives from the Greek sidera, a star, and the terms ‘sidereal’- and ‘star’- zodiac will here have the same meaning, as alluding to a division of the ecliptic into twelve equal sectors. The term ‘zodiac’ will here be used in the sense of these twelve equal divisions of the ecliptic, and will not allude to the unequal constellations that are, as it were, behind the twelve signs. The convergence of the two celestial wheels, tropical and sidereal, meant that the Vernal Point was moving by precession from the sidereal sign of Aries into Pisces, an event comparable to the expectations of present-day astrologers of its movement into Aquarius.