Trajectory Coordinate System Information We Have Calculated the New Horizons Trajectory and Full State Vector Information in 11 Different Coordinate Systems

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Observer's Handbook for 1912

T he O bservers H andbook FOR 1912 PUBLISHED BY THE ROYAL ASTRONOMICAL SOCIETY OF CANADA E d i t e d b y C. A, CHANT FOURTH YEAR OF PUBLICATION TORONTO 198 C o l l e g e St r e e t Pr in t e d fo r t h e So c ie t y 1912 T he Observers Handbook for 1912 PUBLISHED BY THE ROYAL ASTRONOMICAL SOCIETY OF CANADA TORONTO 198 C o l l e g e St r e e t Pr in t e d fo r t h e S o c ie t y 1912 PREFACE Some changes have been made in the Handbook this year which, it is believed, will commend themselves to observers. In previous issues the times of sunrise and sunset have been given for a small number of selected places in the standard time of each place. On account of the arbitrary correction which must be made to the mean time of any place in order to get its standard time, the tables given for a particualar place are of little use any where else, In order to remedy this the times of sunrise and sunset have been calculated for places on five different latitudes covering the populous part of Canada, (pages 10 to 21), while the way to use these tables at a large number of towns and cities is explained on pages 8 and 9. The other chief change is in the addition of fuller star maps near the end. These are on a large enough scale to locate a star or planet or comet when its right ascension and declination are given. -

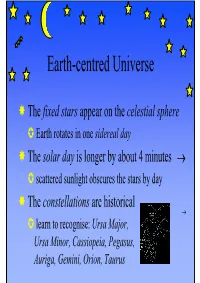

Earth-Centred Universe

Earth-centred Universe The fixed stars appear on the celestial sphere Earth rotates in one sidereal day The solar day is longer by about 4 minutes → scattered sunlight obscures the stars by day The constellations are historical → learn to recognise: Ursa Major, Ursa Minor, Cassiopeia, Pegasus, Auriga, Gemini, Orion, Taurus Sun’s Motion in the Sky The Sun moves West to East against the background of Stars Stars Stars stars Us Us Us Sun Sun Sun z z z Start 1 sidereal day later 1 solar day later Compared to the stars, the Sun takes on average 3 min 56.5 sec extra to go round once The Sun does not travel quite at a constant speed, making the actual length of a solar day vary throughout the year Pleiades Stars near the Sun Sun Above the atmosphere: stars seen near the Sun by the SOHO probe Shield Sun in Taurus Image: Hyades http://sohowww.nascom.nasa.g ov//data/realtime/javagif/gifs/20 070525_0042_c3.gif Constellations Figures courtesy: K & K From The Beauty of the Heavens by C. F. Blunt (1842) The Celestial Sphere The celestial sphere rotates anti-clockwise looking north → Its fixed points are the north celestial pole and the south celestial pole All the stars on the celestial equator are above the Earth’s equator How high in the sky is the pole star? It is as high as your latitude on the Earth Motion of the Sky (animated ) Courtesy: K & K Pole Star above the Horizon To north celestial pole Zenith The latitude of Northern horizon Aberdeen is the angle at 57º the centre of the Earth A Earth shown in the diagram as 57° 57º Equator Centre The pole star is the same angle above the northern horizon as your latitude. -

3.- the Geographic Position of a Celestial Body

Chapter 3 Copyright © 1997-2004 Henning Umland All Rights Reserved Geographic Position and Time Geographic terms In celestial navigation, the earth is regarded as a sphere. Although this is an approximation, the geometry of the sphere is applied successfully, and the errors caused by the flattening of the earth are usually negligible (chapter 9). A circle on the surface of the earth whose plane passes through the center of the earth is called a great circle . Thus, a great circle has the greatest possible diameter of all circles on the surface of the earth. Any circle on the surface of the earth whose plane does not pass through the earth's center is called a small circle . The equator is the only great circle whose plane is perpendicular to the polar axis , the axis of rotation. Further, the equator is the only parallel of latitude being a great circle. Any other parallel of latitude is a small circle whose plane is parallel to the plane of the equator. A meridian is a great circle going through the geographic poles , the points where the polar axis intersects the earth's surface. The upper branch of a meridian is the half from pole to pole passing through a given point, e. g., the observer's position. The lower branch is the opposite half. The Greenwich meridian , the meridian passing through the center of the transit instrument at the Royal Greenwich Observatory , was adopted as the prime meridian at the International Meridian Conference in 1884. Its upper branch is the reference for measuring longitudes (0°...+180° east and 0°...–180° west), its lower branch (180°) is the basis for the International Dateline (Fig. -

Solar Data Handling

United Nations Educational. Scientific The Abdus Salam International Centre for Theoretical Physics Intem3tion.1l Atomic Energy Agency 310/1749-25 ICTP-COST-USNSWP-CAWSES-INAF-INFN International Advanced School on Space Weather 2-19 May 2006 Solar Data Handling Robert BENTLEY UCL Department of Space and Climate Physics Mullard Space Science Laboratory Hombury St. Mary Dorking Surrey RH5 6NT U.K. These lecture notes are intended only for distribution to participants Strada Costiera 11, 34014 Trieste, Italy - Tel. +39 040 2240 11 I; Fax +39 040 224 163 - [email protected], www.ictp.it i f Solar data Handling 1 Rob Bentley University College London (UCL) C Mullard Space Science Laboratory Trieste, 3 May 2006 International Advanced School on Space Weather Nature of Observations Data management issues • Types of data | • Storage of data I • Access to data (current) : • Standards • Temporal and spatial coordinates • File Formats • Types of Metadata I • Data Models egso Nature of solar observations The appearance of the Sun changes dramatically with wavelength • Emissions originate from different layers in the atmosphere and different physical phenomena K • For a complete picture we need to use as 2x106K wide a range of observations as possible 1 • Mixture of types of observations • Different wavelengths and time intervals • Mixture of observations from space- and ground-based platforms 8x104K • Increasing desire to study problems that span communities • Desire relevant to Space Weather, climate I physics, planetary physics, astrophysics 3 • Identifying observations across community 6x10 K boundaries and then retrieving them are major problems r Sun at different wavelengths egso o J K I egso TVPes of Data • Types of data/observation: • single values • spectra (includes and dispersed quantity) • images | • compound - e.g. -

Minima, When the Type B Redauroras Are Predominant. SOLAR

VOL. 43, 1957 GEOPHYSICS: J. BARTELS 75 are being slowed down much higher in the atmosphere than occurs at sunspot minima, when the Type B red auroras are predominant. From the general physical interpretation of the observations of unusual heights of aurora, it seems probable that a consideration of the degree of ionization of the upper atmosphere may account for the wide range found in auroral heights. For this reason the degree of ionization may become one of the problems of auroral morphol- ogy. The auroral program for the International Geophysical Year, 1957-1958, was de- signed with many of the above-mentioned problems in auroral morphology in mind. Hence we may expect to have answers for some of the problems in the next two or three years. 1 J. A. Van Allen, Phys. Rev., 99, 609, 1955. 2 S. Chapman and C. G. Little, J. Atm. and Terrest. Phys. (in press). 3 J. P. Heppner, J. Geophys. Research, 59, 329, 1954. 4 C. W. Gartlein, Nat. Geographic Mag., 92, 683, 1947. 5 F. T. Davies, Transactions of the Oslo Meeting, August 19-928, 1948 (Washington: Interna- tional Union of Geodesy and Geophysics, 1950). 6 A. B. Meinel, Astrophys. J., 113, 50, 1951; 114, 431, 1951. 7 A. B. Meinel and C. Y. Fan, Astrophys. J., 115, 330, 1952. 8 H. Leinbach, Sky and Telescope, 15, 329, 1956. 9 C. T. Elvey, Seventh Alaska Science Conference, Alaska Division, AAAS, Juneau, September 26-29, 1956. 10 C. St0rmer, The Polar Aurora (Oxford: Clarendon Press, 1955). 1 M. Sugiura, Proceedings of the Third Alaska Science Conference, September 22-97, 1962, p. -

Coordinate Systems for Solar Image Data

A&A 449, 791–803 (2006) Astronomy DOI: 10.1051/0004-6361:20054262 & c ESO 2006 Astrophysics Coordinate systems for solar image data W. T. Thompson L-3 Communications GSI, NASA Goddard Space Flight Center, Code 612.1, Greenbelt, MD 20771, USA e-mail: [email protected] Received 27 September 2005 / Accepted 11 December 2005 ABSTRACT A set of formal systems for describing the coordinates of solar image data is proposed. These systems build on current practice in applying coordinates to solar image data. Both heliographic and heliocentric coordinates are discussed. A distinction is also drawn between heliocentric and helioprojective coordinates, where the latter takes the observer’s exact geometry into account. The extension of these coordinate systems to observations made from non-terrestial viewpoints is discussed, such as from the upcoming STEREO mission. A formal system for incorporation of these coordinates into FITS files, based on the FITS World Coordinate System, is described, together with examples. Key words. standards – Sun: general – techniques: image processing – astronomical data bases: miscellaneous – methods: data analysis 1. Introduction longitude and latitude – only need to worry about two spatial dimensions. The same can be said for normal cartography of Solar research is becoming increasingly more sophisticated. a planet such as Earth. However, to properly treat the complete Advances in solar instrumentation have led to increases in spa- range of solar phenomena, from the interior out into the corona, tial resolution, and will continue to do so. Future space mis- a complete three-dimensional coordinate system is required. sions will view the Sun from different perspectives than the Unfortunately, not all the information necessary to determine current view from ground-based observatories, or satellites in the full three-dimensional position of a solar feature is usually Earth orbit. -

Theosophical Siftings the Zodiac Vol 6, No 13 the Zodiac

Theosophical Siftings The Zodiac Vol 6, No 13 The Zodiac by S.G.P. Coryn Reprinted from "Theosophical Siftings" Volume 6 The Theosophical Publishing Society, England [Page 3] OF our nineteenth century researches into the knowledge, the science and the mythology of the ancients, there is probably no department which has given rise to discussion so animated, to speculations so varied, to conclusions often and usually so fallacious, as that of the Zodiac and its twelve signs. Nor need we greatly wonder at the interest which it has evoked. To the sincere student who wishes only for wisdom and understanding, and who does not seek to force and to bend the facts of nature into the mould of his own creed, the Zodiac promises something more than a glimpse into the secrets of the Universe. Almost insensibly to himself he is led to perceive that herein lie the mystic tracings, in divine handwriting, of the world's past and a prophecy of things to come. And on the other side, we find very much the same enthusiasm of research, but directed to the belittling of the history of the Zodiac and to a reduction of its symbology and the mysteries and the myths and the legends which have gathered around it, to the superstition of peoples who knew no written language, nor arts, nor sciences, but believed themselves able to read the signs and the tokens of the heavens above them. And justly may the champions of the creed of a day seek to diminish the importance of the Zodiac, and well may they fear the revelations which it may bring. -

Determining the Rotation Period of the Sun

SOLAR PHYSICS AND TERRESTRIAL EFFECTS 2+ Activity 8 4= Activity 8 Determining the Rotation Period of the Sun Relevant Reading Chapter 2, section 3 Purpose Determine the rotation period of the Sun. Although numerous methods for accurate measurement are used in solar research, the method described here, using photographs taken over several days, will allow determination to within an Earth-day. Materials Photo set that shows at least one solar feature that can be followed over a several-day period. For real challenge, take the photos yourself, or make a simple projection sketch of sunspots over several days. 1 sheet of clear plastic used for overhead transparencies or viewgraphs, or something similar such as a clear plastic report folder a mm ruler, compass and protractor a fine-tipped marking pen suitable for plastic graph paper with 1-mm squares Procedures 1. Measure, to the nearest millimeter, the diameter of the Sun on the photo taken near the middle of the data period. 2. Use a compass and draw a circle with the same diameter on the transpar- ent sheet. 3. With the circle aligned over the photo on the date used for the diameter, trace the axis orientation marks onto the transparency. 4. Pick a solar feature that traverses the solar disk for as many days as pos- sible. Align the circle on the transparency over each successive photo and carefully mark the position of the chosen solar feature along with its date. 5. Carefully draw the best fitting straight line through the marked positions and measure its length across the circle as accurately as possible. -

COORDINATES, TIME, and the SKY John Thorstensen

COORDINATES, TIME, AND THE SKY John Thorstensen Department of Physics and Astronomy Dartmouth College, Hanover, NH 03755 This subject is fundamental to anyone who looks at the heavens; it is aesthetically and mathematically beautiful, and rich in history. Yet I'm not aware of any text which treats time and the sky at a level appropriate for the audience I meet in the more technical introductory astronomy course. The treatments I've seen either tend to be very lengthy and quite technical, as in the classic texts on `spherical astronomy', or overly simplified. The aim of this brief monograph is to explain these topics in a manner which takes advantage of the mathematics accessible to a college freshman with a good background in science and math. This math, with a few well-chosen extensions, makes it possible to discuss these topics with a good degree of precision and rigor. Students at this level who study this text carefully, work examples, and think about the issues involved can expect to master the subject at a useful level. While the mathematics used here are not particularly advanced, I caution that the geometry is not always trivial to visualize, and the definitions do require some careful thought even for more advanced students. Coordinate Systems for Direction Think for the moment of the problem of describing the direction of a star in the sky. Any star is so far away that, no matter where on earth you view it from, it appears to be in almost exactly the same direction. This is not necessarily the case for an object in the solar system; the moon, for instance, is only 60 earth radii away, so its direction can vary by more than a degree as seen from different points on earth. -

The Succession of World Ages Jane B

The Succession of World Ages Jane B. Sellers From The Death of Gods in Ancient Egypt © 1992, 2007 by Jane Sellers aking up the challenge laid been the product of a long development, for down in Hamlet’s Mill to find it is not until the fourth century bc that we Tarchaeoastronomical origins for find the first use of signs for these segments. many of humanity’s myths, Jane Sellers But certainly by 700 bc, in a Babylonian text undertook to discover the correlations between known as MUL.APIN the path of the sun was the astronomical knowledge of the ancient divided into 4 parts with the sun spending Egyptians and their mythic structures. In this three months in each. Since the months were selection, she discusses the precession of the usually reckoned to have 30 days, it easily equinoxes, vital to the understanding of the followed that the monthly segments of the Mithraic Mysteries. Hipparchus may have zodiac would be each assigned 30 “degrees.” rediscovered this astronomical phenomenon, Antiquity of the Zodiac however, it is clear that the Egyptians were Many astronomers harbor a belief that aware of it centuries before. the division of the sun’s path into twelve At the moment of the Spring equal segments far predated this text. Equinox the heavens are never in Charles A. Whitney, Professor of Astronomy quite the same position they were at Harvard, in Whitney’s Starfinder, 1986– in the year before, since there is a 89 writes, “Three thousand years ago and very slight annual lag of about 50 perhaps longer—astronomers chose the seconds, which in the course of sun signs according to the corresponding 72 years amounts to 1 degree (50 zodiacal constellations, and they set Aries at seconds x 72 years = 3,600 seconds the spring equinox.”2 = 60 minutes = 1 degree) and in 2,160 years amounts to 30 degrees, which is one “sign” of the zodiac. -

On the Determination and Constancy of the Solar Oblateness

On the determination and constancy of the solar oblateness Mustapha Meftah, Abdanour Irbah, Alain Hauchecorne, Thierry Corbard, Sylvaine Turck-Chièze, Jean-François Hochedez, Patrick Boumier, A. Chevalier, S. Dewitte, S. Mekaoui, et al. To cite this version: Mustapha Meftah, Abdanour Irbah, Alain Hauchecorne, Thierry Corbard, Sylvaine Turck-Chièze, et al.. On the determination and constancy of the solar oblateness. Solar Physics, Springer Verlag, 2015, 290 (3), pp.673-687. 10.1007/s11207-015-0655-6. hal-01110569 HAL Id: hal-01110569 https://hal.archives-ouvertes.fr/hal-01110569 Submitted on 16 Nov 2016 HAL is a multi-disciplinary open access L’archive ouverte pluridisciplinaire HAL, est archive for the deposit and dissemination of sci- destinée au dépôt et à la diffusion de documents entific research documents, whether they are pub- scientifiques de niveau recherche, publiés ou non, lished or not. The documents may come from émanant des établissements d’enseignement et de teaching and research institutions in France or recherche français ou étrangers, des laboratoires abroad, or from public or private research centers. publics ou privés. Solar Phys (2015) 290:673–687 DOI 10.1007/s11207-015-0655-6 On the Determination and Constancy of the Solar Oblateness M. Meftah1 · A. Irbah1 · A. Hauchecorne1 · T. Corbard2 · S. Turck-Chièze3 · J.-F. Hochedez1,4 · P. Boumier 5 · A. Chevalier6 · S. Dewitte6 · S. Mekaoui6 · D. Salabert3 Received: 19 November 2013 / Accepted: 21 January 2015 / Published online: 11 February 2015 © The Author(s) 2015. This article is published with open access at Springerlink.com Abstract The equator-to-pole radius difference (r = Req −Rpol) is a fundamental property of our star, and understanding it will enrich future solar and stellar dynamical models. -

Can We Observe X Tonight?

Massachusetts Institute of Technology Department of Earth, Atmospheric, and Planetary Sciences 12.409 Observing Stars and Planets, Spring 2002 Handout 4 week of February 11, 2002 Copyright 1999 Created S. Slivan Revised A. Rivkin and J. Thomas-Osip Can We Observe x Tonight? This is an important question to be able to answer, this being an observing subject and all. The answer to this question is “yes” only if the answer to the following 4 questions is “yes”: 1.Is the weather cooperating? 2.Is x bright enough, given our observing equipment? 3.Is the sky dark enough? 4.Is x high enough above our horizon? This handout addresses the answering of questions 2, 3, and 4, and explains how to use information published in the Astronomical Almanac to decide whether to go for a specific object at any given time. As for question 1, that's a different class... (12.310) Contents 1 Brightness Scale........................................................................................................... 2 1.1 Effects on apparent brightness ............................................................................... 3 2 Coordinate Systems...................................................................................................... 4 2.1 Terrestrial coordinates........................................................................................... 4 2.2 Celestial coordinates.............................................................................................. 5 2.3 Observer-based coordinates..................................................................................