Mental Health at Ambrose University Strategies for Change

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Rev. Raymond C. Aldred

Rev. Raymond C. Aldred Assistant Professor of Theology Ambrose Seminary/Ambrose University Ministry Trainer/Director My People International Board Chair Indigenous Pathways Address 1168 Berkley Drive NW Calgary, AB T3K 1S7 Home: 403-475-3994 Fax: 403-571-2556 Cellular: 403-771-1187 Email: [email protected] Personal` Born January 23, 1960, in Grande Prairie, AB Treaty 8 First Nation Person Married to Elaine Aldred; two daughters, two sons Skills Class 3 Alberta Driver’s License Indigenous Story Teller Author On-line course development and delivery Interests Hunting and Fishing Run 15-20 miles per week Traditional Indigenous music and dance 1 Education Wycliffe College at TST ThD program in progress London School of Theology Ph.D. program September 2004 – October 2013 unfinished Canadian Theology Seminary M.Div. highest honours, 2000 Canadian Bible College B.TH. highest honours, 1992 Employment Assistant Professor of Theology Ambrose Seminary/Ambrose University 2007-present My People International: Family Programs 2004-present Facilitate training of aboriginal leaders Adjunct Professor, North American Institute for Indigenous Theological Studies: Theology 2011-Present Circle Drive Alliance Church Aboriginal Consultant, November 2012-Present Rocky Mountain Bible College Fall 2013, Fall 2010 Adjunct professor Canadian aboriginal cultures Visiting Professor July 2014, July, 2006, 2014 Vancouver School of Theology: Native Consortium, Vancouver, BC Adjunct Professor August, 2005 William Catherine Booth College, Winnipeg, MB Adjunct Professor -

Participating Universities and Colleges: Acadia University Algoma University Algonquin College Ambrose University Assiniboine C

Participating universities and colleges: Acadia University Cégep de Thetford Algoma University Cégep de Trois-Rivières Algonquin College Cégep de Victoriaville Ambrose University Cégep du Vieux Montréal Assiniboine Community College Cégep régional de Lanaudière à Joliette Bishop’s University Centennial College Booth University College Centre d'études collégiales de Montmagny Brandon University Champlain College Saint-Lambert Brescia University College Collège Ahuntsic Brock University Collège d’Alma Cambrian College Collège André-Grasset Camosun College Collège Bart Canadian Mennonite University Collège de Bois-de-Boulogne Canadore College Collège Boréal Cape Breton University Collège Ellis Capilano University Collège Jean-de-Brébeuf Carleton University Collège Laflèche Carlton Trail College Collège LaSalle Cégep de l’Abitibi-Témiscamingue Collège de Maisonneuve Cégep de Baie-Comeau Collège Montmorency Cégep de Chicoutimi College of the North Atlantic Cégep de Drummondville Collège O’Sullivan de Montréal Cégep Édouard-Montpetit Collège O’Sullivan de Québec Cégep de la Gaspésie et des Îles College of the Rockies Cégep Gérald-Godin Collège TAV Cégep de Granby Collège Universel Gatineau Cégep Heritage College Collégial du Séminaire de Sherbrooke Cégep de Jonquière Columbia Bible College Cégep de Lévis Concordia University Cégep Marie-Victorin Concordia University of Edmonton Cégep de Matane Conestoga College Cégep de l’Outaouais Confederation College Cégep La Pocatière Crandall University Cégep de Rivière-du-Loup Cumberland College Cégep Saint-Jean-sur-Richelieu Dalhousie University Cégep de Saint-Jérôme Dalhousie University Agricultural Campus Cégep de Sainte-Foy Douglas College Cégep de St-Félicien Dumont Technical Institute Cégep de Sept-Îles Durham College Cégep de Shawinigan École nationale d’administration publique Cégep de Sorel-Tracy (ENAP) Cégep St-Hyacinthe École de technologie supérieure (ÉTS) Cégep St-Laurent Fanshawe College of Applied Arts and Cégep St. -

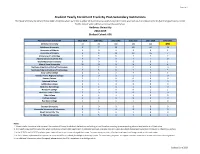

Student Yearly Enrolment Track by Post-Secondary Institutions

Page 1 of 1 Student Yearly Enrolment Track By Post-Secondary Institutions The Student Yearly Enrolment Track table identifies where were the number of students in an institution (cohort size) who had valid enrolment records (full time/part time) in LERS for the cohort year and five years prior by institution. Ambrose University 2018-2019 Student Cohort: 696 Post-Secondary Institution 2013-2014 2014-2015 2015-2016 2016-2017 2017-2018 2018-2019 Ambrose University 33 83 180 284 421 696 Athabasca University Athabasca University 4 7 13 18 26 39 University of Alberta University of Alberta 3 0 2 0 0 2 University of Calgary University of Calgary 6 8 10 12 16 7 University of LethbridgeUniversity of Lethbridge 3 3 6 7 3 2 Alberta University ofAlberta the Arts University of the Arts 4 4 3 2 1 0 Grant MacEwan UniversityGrant MacEwan University 0 0 0 0 0 1 Mount Royal UniversityMount Royal University 10 12 8 9 6 4 Northern AlbertaNorthern Institute Alberta of Technology Institute of Technology 2 2 0 0 0 0 Southern AlbertaSouthern Institute Alberta of Technology Institute of Technology 9 6 6 7 2 3 Bow Valley College Bow Valley College 1 1 3 4 7 5 Grande Prairie RegionalGrande College Prairie Regional College 1 0 2 1 1 0 Keyano College Keyano College 1 1 0 0 0 0 Lakeland College Lakeland College 0 1 0 0 0 0 Lethbridge College Lethbridge College 0 1 0 0 0 0 Medicine Hat College Medicine Hat College 1 2 0 1 0 0 NorQuest College NorQuest College 0 0 0 0 1 1 Northern Lakes CollegeNorthern Lakes College 0 0 0 0 0 0 Olds College Olds College 1 1 1 1 0 0 Portage College Portage College 0 0 0 0 0 0 Red Deer College Red Deer College 0 1 1 1 2 0 Ambrose University - - - - - - - Burman University Burman University 0 0 0 0 0 0 Concordia UniversityConcordia of Edmonton University of Edmonton 0 0 0 0 0 0 King's University, The King's University, The 1 1 4 2 0 0 St. -

BC's Faith-Based Postsecondary Institutions

Made In B.C. – Volume II A History of Postsecondary Education in British Columbia B.C.’s Faith-Based Postsecondary Institutions Bob Cowin Douglas College April 2009 The little paper that keeps growing I had a great deal of fun in 2007 using some of my professional development time to assemble a short history of public postsecondary education in British Columbia. My colleagues’ interest in the topic was greater than I had anticipated, encouraging me to write a more comprehensive report than I had planned. Interest was such that I found myself leading a small session in the autumn of 2008 for the BC Council of Post Secondary Library Directors, a group that I enjoyed meeting. A few days after the session, the director from Trinity Western University, Ted Goshulak, sent me a couple of books about TWU. I was pleased to receive them because I already suspected that another faith-based institution, Regent College in Vancouver, was perhaps BC’s most remarkable postsecondary success. Would Trinity Western’s story be equally fascinating? The short answer was yes. Now I was hooked. I wanted to know the stories of the other faith-based institutions, how they developed and where they fit in the province’s current postsecondary landscape. In the ensuing months, I poked around as time permitted on websites, searched library databases and catalogues, spoke with people, and circulated drafts for review. A surprisingly rich set of historical information was available. I have drawn heavily on this documentation, summarizing it to focus on organizations rather than on people in leadership roles. -

Making Connections Forging Links to Opportunity, Careers, Vision and Faith at Ambrose

SPRING 2017 THE MAGAZINE OF AMBROSE UNIVERSITY Making Connections Forging links to opportunity, careers, vision and faith at Ambrose It takes a village | The art of Christianity | Something fishy | Rethinking holiness Use your power for good. Make the switch today. Switch your electricity or natural gas at home or work to Sponsor Energy and fund the Canadian Poverty Institute (CPI) at Ambrose University. • Get the same price or better than your current provider • Cancel at any time without penalty • 50% of the profit on your energy use goes to the CPI Help us prevent and eradicate poverty by switching to Sponsor Energy today. It’s easy and makes a difference at no cost to you or your business. We believe it’s Sponsor possible to make Energy is money and make a difference. Half of our profit goes to a charity based on a of your choice — at no extra cost. simple idea: We’re part of a growing movement by industry to do more and to do better. To do good. A movement that empowers people to take small actions individually can have a big impact sponsorenergy.com collectively. All it takes is a few minutes of your time. 1-855-545-1160ambrose university 6 It takes a village Answering the question of poverty in Canada requires ideas and inspiration from across the nation. The new and innovative Poverty Studies Summer Institute brings passion and minds together. 8 8 Spotlight: Connecting and courts Dr. Monetta Bailey’s research shows how Canada’s anthem commitment to multiculturalism needs to extend into to the youth justice system — to keep more immigrant youth out of court. -

NSSE 2013 Selected Comparison Groups Cape Breton University

NSSE 2013 Selected Comparison Groups Cape Breton University PSIS: 12003000 NSSE 2013 Selected Comparison Groups Interpreting Your Report Customized Comparison Groups The NSSE Institutional Report displays core survey results for your students alongside those of three comparison groups. In June, your institution was invited to customize these groups via the "Report Form" on the Institution Interface. This report summarizes how your comparison groups were selected and lists the institutions within them. NSSE comparison groups may be customized by (a) identifying specific institutions from the list of all current-year participants, (b) composing the group by selecting institutional characteristics, or (c) a combination of these. Institutions that choose not to customize receive default groupsa that provide relevant comparisons for most institutions. Institutions that appended additional question sets in the form of topical modules or through consortium participation were also invited to customize comparison groups for the corresponding reports by choosing from the institutions where the question sets were administered. The default for these groups is all other institutions where the questions were included. Please note: Comparison groups for additional question sets (topical modules and consortium questions) are documented within those reports. Your Students' Comparison Comparison Comparison Report Comparisons Responses Group 1 Group 2 Group 3 Comparison groups are located in the institutional reports as illustrated in the mock report at right. The three groups are "Public Research Univ," "Large Public," and "NSSE 2013." Reading This Report This report consists of Comparison Group Name three sections that The name assigned to the provide details for each comparison group is listed here. of your comparison groups, illustrated at How Group was Selected Indicates whether your group was right. -

Ambrose Residence a Place to Belong

anthemThe magazine of Ambrose University College FALL/WINTER 2010/11 Ambrose Residence A Place to Belong Inside 3 Learning the Craft of Teaching In the Ambrose Bachelor of Education program mentoring relationships between veteran and student teachers is the way learning is done “up on the hill”. 11 Learning in the Residence VP Student Life Wally Rude sees residence life as a significant factor in the creation of a positive campus culture and in the development of students. 13 Space to Grow Construction has started on the new Residence & Education Centre. This new building will give Ambrose capacity for the 1000 plus students expected on campus by 2014. 23 Dr Barry Moore on Campus Evangelist Dr Barry Moore spoke to students during the recent Spiritual Emphasis days. Dr Moore’s visit to Ambrose was part of his cross- Canada tour celebrating 50 years of ministry. 2 Editorial 5 Profiles 8 Lions Athletics 18 Educational Travel 22 Anthem Extras 24 Family Ties 29 Final Word Residence is an experience that creates the kind of deep friendships between students that last a lifetime. Residence truly helps make Ambrose a place to belong. Fall/Winter 2010/11 anthem 1 anthem The magazine of Ambrose University College A Place to Belong Fall/Winter 2010/11 PRESIDENT AND EXECUTIVE EDITOR Howard Wilson Belonging is more than being together, CHANCELLOR AND ACTING VP it is also about our identity. So what EXTERNAL RELATIONS identifies an Ambrose student today? Here Riley Coulter DIRECTOR OF DEVELOPMENT are some clues. AND EDITOR I recently heard a student mention Kim Follis with pride that when she was hired by a DIRECTOR OF COMMUNICATIONS AND MARKETING nearby retail store she was told that she Wes Campbell Kim Follis was one of several Ambrose students who EXECUTIVE ASSISTANT AND Editor are employed there. -

Annual Report 2019-2020 Prepared for the Ministry of Advanced Education Ambrose University 150 Ambrose Circle SW Calgary, Alberta T3H 0L5

Annual Report 2019-2020 Prepared for the Ministry of Advanced Education Ambrose University 150 Ambrose Circle SW Calgary, Alberta T3H 0L5 www.ambrose.edu 22 COMPREHENSIVE INSTITUTIONAL PLAN 2014-2017 Annual Report Academic Year 2019-2020 For Alberta Advanced Education Contents 1. Accountability Statement ..................................................................................................................... 2 2. Management’s Responsibility for Reporting ........................................................................................ 2 3. Message from the President ................................................................................................................. 2 4. Public Interest Disclosure (Whistleblower Protection) Act .................................................................. 3 5. Operational Overview ........................................................................................................................... 3 6. Goals, Priority Initiatives, Expected Outcomes and Performance Measures ....................................... 6 Accessibility ............................................................................................................................................... 6 Affordability ............................................................................................................................................ 14 Quality .................................................................................................................................................... -

Seminary Academic Calendar 2020-2021

SEMINARY ACADEMIC CALENDAR 2020-2021 Contents Seminary Academic Calendar ................................................................................................................................................. 1 Important Information .................................................................................................................................................... 1 Know Your Policies and Regulations ............................................................................................................................... 1 Disclaimer: This Calendar is Subject to Change .............................................................................................................. 1 Land Acknowledgement .................................................................................................................................................. 1 A Message from the President ................................................................................................................................................ 2 2020 - 2021 Academic Schedule ............................................................................................................................................. 3 Fall Semester ................................................................................................................................................................... 3 Winter Semester ............................................................................................................................................................ -

List of Canada Higher Educational Institutions Recognized by China

List of Canada Higher Educational Institutions Recognized by China Government Universities Alberta Ambrose University Burman University Concordia University of Edmonton Grant MacEwan University Mount Royal University St. Mary’s University The King’s University University of Alberta University of Calgary University of Lethbridge Capilano University Emily Carr University of Art and Design Kwantlen Polytechnic University Royal Roads University Simon Fraser University The University of British Columbia Thompson Rivers University Trinity Western University University of Northern British Columbia University of the Fraser Valley University of Victoria Vancouver Island University Quest University Canada University Canada West Manitoba Brandon University The University of Manitoba The University of Winnipeg New Brunswick Mount Alison University St. Thomas University Université de Moncton University of New Brunswick Newfoundland & Labrador Memorial University of Newfoundland Nova Scotia Acadia University Cape Breton University (originally known as University College of Cape Breton) Dalhousie University Mount Saint Vincent University NSCAD University Saint Mary’s University St. Francis Xavier University Université Sainte-Anne Ontario Algoma University (originally under Laurentian University) Brock University Carleton University Lakehead University Laurentian University McMaster University Nipissing University OCAD University Queen’s University Ryerson University Saint Paul University St. Jerome’s University Trent University University of Guelph -

Irving Hexham Academic Curriculum Vitae March 2011

Irving Hexham Academic Curriculum Vitae March 2011 Present posts Professor, Department of Religious Studies, University of Calgary, and address: 2500 University Drive N.W., Calgary, Alberta, Canada, T2N 1N4. University of Calgary, 2007-present Adjunct Professor, Liverpool Hope University, 2005-present Telephone: (01) 403-220-5886 Fax: (01) 403-210-9191 E-Mail: [email protected] Web Sites: http://www.ucalgary.ca/~hexham Qualifications: Ph.D., History, University of Bristol, 1975 M.A. “with commendation,” Theology and Religious Studies, University of Bristol, 1972 B.A. (Hons.), Religious Studies, University of Lancaster, 1970 University Matriculation, by correspondence study, five British “A” levels, 1967 Lecturing and teaching course, North Western Gas Board, 1966 Management training course, North Western Gas Board, 1964 Advanced Diploma, Industrial Gas Technology, 1964 Intermediate Diploma, Domestic Gas Technology, 1963 City & Guilds, Certificate, Gas Fitting, 1962 Academic Honors and Recognition: Fellow of the Royal Historical Society, 2010 – present. Fellow of the Centre for Military and Strategic Studies, University of Calgary, 2007 - present. Fellow of the Royal Anthropological Institute, 1975 - present. Festschrift: Border Crossings: The Explorations of an Inter-disciplinary Historian, edited by Ulrich van der Heyden and Andreas Feldtkeller, Stuttgart, Franz Steiner Verlag, 2008. Presented at the Humboldt University in Berlin, May 23, 2008. One of the few Religious Studies professors listed in Who’s Who in Canada, 1995-present. Visiting Professor, Humboldt University, Berlin, Spring Semester, 2003. Academic consultant to: the Canadian Government’s Department of Canadian Heritage, 2002. Academic consultant to: the United Nations High Commissioner for Refugees, 2002. Academic consultant with the CBC, Canadian Broadcasting Corporation, since 1989. -

Application for Name Change

3377 Bayview Avenue TEL: 416.226.6620 Toronto, ON www.tyndale.ca M2M 3S4 Application for Name Change Executive Summary Tyndale University College & Seminary was established through an act of legislation in 2003 as a natural progression of over 125 years of history of providing post-secondary education in the province of Ontario. The change in legislation afforded Tyndale the opportunity to provide undergraduate university quality education through a series of Bachelor of Arts (BA) degrees to complement a thriving graduate school (Tyndale Seminary) whose recognition as a tier one graduate school for theological education and counselling psychotherapy was known throughout North America. The undergraduate programs have complemented the graduate school by providing a quality undergraduate university opportunity. Undergraduate student learning outcomes are similar to any BA program in the province; however, the nomenclature University College has proven difficult to explain and market. Tyndale is one of only two independent University Colleges in the province not federated/affiliated with any institutional member of the Council of Ontario Universities. Students and families who are making post-secondary decisions are, therefore, unfamiliar with the term and interpret it to mean something less than a university degree. In jurisdictions outside of Ontario, most of the provinces have moved away from the nomenclature of University College preferring that all of their undergraduate universities are known as Universities. This has created a hardship in our ability to attract students both from within and outside of the province. We strongly believe that a private faith based university in the city of Toronto can attract and grow its enrolment by attracting students from other Canadian jurisdictions while at the same time keeping students in Ontario who are considering our competitors.