General Editor's Introduction

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Andrea-Bianka Znorovszky

10.14754/CEU.2016.06 Doctoral Dissertation Between Mary and Christ: Depicting Cross-Dressed Saints in the Middle Ages (c. 1200-1600) By: Andrea-Bianka Znorovszky Supervisor(s): Gerhard Jaritz Marianne Sághy Submitted to the Medieval Studies Department, and the Doctoral School of History (HUNG doctoral degree) Central European University, Budapest of in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in Medieval Studies, and for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in History(HUNG doctoral degree) CEU eTD Collection Budapest, Hungary 2016 10.14754/CEU.2016.06 I, the undersigned, Andrea-Bianka Znorovszky, candidate for the PhD degree in Medieval Studies, declare herewith that the present dissertation is exclusively my own work, based on my research and only such external information as properly credited in notes and bibliography. I declare that no unidentified and illegitimate use was made of the work of others, and no part of the thesis infringes on any person’s or institution’s copyright. I also declare that no part of the thesis has been submitted in this form to any other institution of higher education for an academic degree. Budapest, 07 June 2016. __________________________ Signature CEU eTD Collection i 10.14754/CEU.2016.06 ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS In the dawn, after a long, perilous journey, when, finally, the pilgrim got out from the maze and reached the Holy Land, s(he) is still wondering on the miraculous surviving from beasts, dragons, and other creatures of the desert who tried to stop its travel. Looking back, I realize that during this entire journey I was not alone, but others decided to join me and, thus, their wisdom enriched my foolishness. -

Archivum Historicum Societatis Iesu

ARCHIVUM HISTORICUM SOCIETATIS IESU VOL. LXXXII, FASC. 164 2013/II Articles Charles Libois S.J., L’École des Jésuites au Caire dans l’Ancienne Compagnie. 355 Leonardo Cohen, El padre Pedro Páez frente a la interpretación bíblica etíope. La controversia sobre “cómo llenar una 397 brecha mítica”. Claudia von Collani, Astronomy versus Astrology. Johann Adam Schall von Bell and his “superstitious” Chinese Calendar. 421 Andrea Mariani, Mobilità e formazione dei Gesuiti della Confederazione polacco-lituana. Analisi statistico- prosopografica del personale dei collegi di Nieśwież e Słuck (1724-1773). 459 Francisco Malta Romeiras, The emergence of molecular genetics in Portugal: the enterprise of Luís Archer SJ. 501 Bibliography (Paul Begheyn S.J.) 513 Book Reviews Charlotte de Castelnau-L’Estoile et alia, Missions d’évangélisation et circulation des savoirs XVIe- XVIIIe siècle (Luce Giard) 633; Pedro de Valencia, Obras completas. VI. Escritos varios (Doris Moreno) 642; Wolfgang Müller (Bearb.), Die datierten Handschriften der Universitätsbibliothek München. Textband und Tafelband (Rudolf Gamper) 647; Ursula Paintner, Des Papsts neue Creatur‘. Antijesuitische Publizistik im Deutschsprachigen Raum (1555-1618) (Fabian Fechner) 652; Anthony E. Clark, China’s Saints. Catholic Martyrdom during the Qing (1644-1911) (Marc Lindeijer S.J.) 654; Thomas M. McCoog, “And touching our Society”: Fashioning Jesuit Identity in Elizabethan England (Michael Questier) 656; Festo Mkenda, Mission for Everyone: A Story of the Jesuits in East Africa (1555-2012) (Brendan Carmody S.J.) 659; Franz Brendle, Der Erzkanzler im Religionskrieg. Kurfürst Anselm Casimir von Mainz, die geistlichen Fürsten und das Reich 1629 bis 1647 (Frank Sobiec) 661; Robert E. Scully, Into the Lion’s Den. -

SJ Liturgical Calendar

SOCIETY OF JESUS PROPER CALENDAR JANUARY 3 THE MOST HOLY NAME OF JESUS, Titular Feast of the Society of Jesus Solemnity 19 Sts. John Ogilvie, Priest; Stephen Pongrácz, Melchior Grodziecki, Priests, and Mark of Križevci, Canon of Esztergom; Bl. Ignatius de Azevedo, Priest, and Companions; James Salès, Priest, and William Saultemouche, Religious, Martyrs FEBRUARY 4 St. John de Brito, Priest; Bl. Rudolph Acquaviva, Priest, and Companions, Martyrs 6 Sts. Paul Miki, Religious, and Companions; Bl. Charles Spinola, Sebastian Kimura, Priests, and Companions; Peter Kibe Kasui, Priest, and Companions, Martyrs Memorial 15 St. Claude La Colombière, Priest Memorial MARCH 19 ST. JOSEPH, SPOUSE OF THE BLESSED VIRGIN MARY, Patron Saint of the Society of Jesus Solemnity APRIL 22 THE BLESSED VIRGIN MARY, MOTHER OF THE SOCIETY OF JESUS Feast 27 St. Peter Canisius, Priest and Doctor of the Church Memorial MAY 4 St. José María Rubio, Priest 8 Bl. John Sullivan, Priest 16 St. Andrew Bobola, Priest and Martyr 24 Our Lady of the Way JUNE 8 St. James Berthieu, Priest and Martyr Memorial 9 St. Joseph de Anchieta, Priest 21 St. Aloysius Gonzaga, Religious Memorial JULY 2 Sts. Bernardine Realino, John Francis Régis and Francis Jerome; Bl. Julian Maunoir and Anthony Baldinucci, Priests 9 Sts. Leo Ignatius Mangin, Priest, Mary Zhu Wu and Companions, Martyrs Memorial 31 ST. IGNATIUS OF LOYOLA, Priest and Founder of the Society of Jesus Solemnity AUGUST 2 St. Peter Faber, Priest 18 St. Alberto Hurtado Cruchaga, Priest Memorial SEPTEMBER 2 Bl. James Bonnaud, Priest, and Companions; Joseph Imbert and John Nicolas Cordier, Priests; Thomas Sitjar, Priest, and Companions; John Fausti, Priest, and Companions, Martyrs 9 St. -

Ignatian Laity: Discipleship, in Community, for Mission1

IGNATIAN LAITY: DISCIPLESHIP, IN COMMUNITY, FOR MISSION1 Samuel Yáñez Professor of Philosophy, Universidad Alberto Hurtado Member of CLC Santiago, Chile he Second Vatican Council dealt with the Church primarily from the perspective of what unites all T Christians. From this common point of view, it addressed the specifics of each vocation (lay, religious, priestly.) Inspired by the Council, the Church strives, in its comings and goings, in the task of giving birth historically to a Church that is the People of God, which is the theological category used by the Council. This also has been seen in what can be called the “Ignatian world,” that is, in the realm, not closed but rather open, of those who live out Christianity along the spiritual path opened by St. Ignatius of Loyola. One expression of this fact is that, in the last two General Congregations of the Society of Jesus, the theme of collaboration has given rise to two Decrees: Decree 13 of GC 34 and Decree 6 of GC 35. In Chile, collaboration is already producing fruit through service, for example, in education, in the renewal of the experience of the Spiritual Exercises, in social promotion, in the evangelization of culture, in the service of those in any need. In this context, I propose to try to respond to two questions. The first is: How ought we to think about the theme of collaboration between Jesuits – religious and or priests – NUMBER 125 - Review of Ignatian Spirituality 87 DISCIPLESHIP, IN COMMUNITY, FOR MISSION and laypeople? The second question is: What would be the essential elements that a lay Ignatian would have to possess to be considered as such? In order to avoid having to repeat each time “lay men and women” I will speak of “laypersons” or sometimes “laymen.” But I always mean to be speaking of both women and men. -

JANUARY 2007 MONDAY 1 (19 Dec.) Martyr Boniface at Tarsus in Cilicia (+290), and Righteous Aglae (Aglaida) of Rome

JANUARY 2007 MONDAY 1 (19 Dec.) Martyr Boniface at Tarsus in Cilicia (+290), and Righteous Aglae (Aglaida) of Rome. Martyrs Elias, Probus, and Ares, in Cilicia (+308). Martyrs Polyeuctus at Caeasarea in Cappadocia, and Timothy the deacon. St. Boniface the Merciful, bishop of Ferentino (VI cent.). St. Gregory, archbishop of Omirits (+c. 552). St. Elias, wonderworker of the Kyiv Caves (+c. 1188). Heb. 11, 17-23, 27-31 Mk. 9, 42 - 10, 1 TUESDAY 2 (20 Dec.) Prefestive of the Nativity of Christ. Hieromartyr Ignatius the God-bearer, bishop of Antioch (+107). St. Philogonius, bishop of Antioch (+c. 323). St.Daniel, archbishop of Serbia (+1338). Venerable Ignatius, archimandrite of the Kyiv Caves (+1435). Heb. 4, 14 – 5, 10 Mt. 5, 14-19 WEDNESDAY 3 (21 Dec.) Virgin-martyr Juliana and with her 500 men and 130 women in Nicomedia (+304). Martyr Themistocles of Myra and Lycia (+251). Repose of St. Peter, metropolitan of Kyiv and all- Rus’-Ukraine (1326). Heb. 7, 26 – 8, 2 Lk. 6, 17-23 THURSDAY 4 (22 Dec.) Great-martyr Anastasia, and her teacher Chrysogonus, and with them martyrs Theodota, Evodias, Eutychianus, and others who suffered under Diocletian (+c. 304). Gal. 3, 23-29 Lk. 7, 36-50 FRIDAY 5 (23 Dec.) Holy ten martyrs of Crete: Theodulus, Euporus, Gelasius, Eunychius, Zoticus, Pompeius, Agathopusus, Basilidus and Evarestes (III cent.).St. Niphon, bishop of Cyprus (IV cent.). St. Paul, bishop of Neo-Caesaraea (IV cent.). 1 January 2007 The Royal Hours: First Hour: Micah 5, 2-4 Heb. 1, 1-12 Mt. 1, 18-25 Third Hour: Baruch 3, 36 – 4, 4 Gal. -

Here Gender Bias Among Voters? Evidence from the Chilean Congressional Elec- Tions

Francisco J. Pino Department of Economics Contact School of Economics and Business phone: +56-(2) 2977-2068 Information University of Chile e-mail: [email protected] Diagonal Paraguay 257 website: http://www.franciscopino.com Santiago, Chile Academic Assistant Professor of Economics August 2015 to present Appointments Department of Economics, University of Chile Research Affiliate August 2015 to present COES - Centre for Social Conflict and Cohesion Studies Research Fellow July 2019 to present IZA (Institute for the Study of Labor) Previous Postdoctoral Researcher July 2012 to July 2015 Academic ECARES, Université Libre de Bruxelles Appointments Education Boston University, Boston, MA Ph.D., Economics, May 2012 M.A., Political Economy, May 2010 University of Chile, Santiago, Chile B.S., Electrical Engineering, December 2001 B.S., Industrial Engineering, December 2001 Fields of Primary Fields: Political Economy, Economic History and Economics of Gender Interest Secondary Fields: Development Economics and Labor Economics Publications The Tyranny of the Single Minded: Guns, Environment, and Abortion, with Lau- rent Bouton, Paola Conconi and Maurizio Zanardi. Review of Economics and Statistics, 103(1), 48-59. 2021. Property Rights and Gender Bias: Evidence from Land Reform in West Bengal, with Sonia Bhalotra, Abhishek Chakravarty and Dilip Mookherjee. American Economic Journal: Applied Economics, 11(2), 205-237. 2019. The Evolution of Land Distribution in West Bengal 1967-2003: Role of Land Re- form, with Pranab Bardhan, Mike Luca and Dilip Mookherjee. Journal of Development Economics 110, 171-190. 2014. 1 of 5 Chilean Pension Reform: Coverage Facts and Policy Alternatives, with Solange Berstein and Guillermo Larraín. Journal Economía 6, 125-137. -

Forever I Will Sing the Goodness of the Lord. PARISH WEEKLY

20 December 2020 Queenship of Mary Church Fourth Sunday Northampton, PA of Advent PARISH WEEKLY Rev. Patrick H. Lamb, Pastor Msgr. John S. Campbell, Pastor Emeritus Msgr. Michael J. Chaback, In Residence Deacon Michael W. Doncsecz Mrs. Maureen Tancin, Secretary Mrs. Stephanie Kalavoda, PREP THE CELEBRATION OF MASS Saturday Evening: 4:00 PM Sunday: 8:00, 10:30 AM Mon.Tues. M Wed. 8:00AM Thurs. NO MASS Friday: 9:15AM (SCHOOL MASS) HOLY DAY MASSES 6:30AM, 9:00AM, 7:00PM SACRAMENT OF PENANCE Saturday: 3:00 to 3:45 PM Sunday: 10:00 to 10:25 AM Other times by appointment Forever I will sing the SACRAMENT OF BAPTISM Baptisms are celebrated on the 4th Sunday of the goodness of the Lord. month. A prebaptismal workshop is required for par- ents, who are expected to be active members for at least three months. Please call Deacon Mike to make RECTORY all arrangements. (6102622227) 1324 Newport Avenue HOLY MATRIMONY Northampton, PA 18067 A minimum preparation time of six months is required Phone: 610 2622227 for the couple by the Diocese for the proper celebra- Fax: 610 2624192 tion of the Sacrament. Please call Father Lamb to Email: [email protected] make all arrangements. (6102622227) Website: queenshipofmary.weconnect.com RECTORY OFFICE HOURS WE WELCOME Monday to Thursday: 9:00AM to 3:00PM NEW PARISHIONERS Friday: 9:00AM to 2:00PM Please introduce yourselves to Father Lamb or Deacon Mike after Mass. CONVENT PHONE (610) 4400134 PROTECTING GOD’S CHILDREN CONVENT ADDRESS 1314 NEWPORT AVE. OfLice of Safe Environment NORTHAMPTON PA 18067 Pamela J. -

Following the Way of Ignatius, Francis Xavier and Peter Faber,Servants Of

FOLLOWING THE WAY OF IGNATIUS, FRANCIS XAVIER AND PETER FABER, SERVANTS OF CHRIST’S MISSION* François-Xavier Dumortier, S.J. he theme of this meeting places us in the perspective of the jubilee year, which recalls to us the early beginnings of the Society of Jesus. What is the aim of thisT jubilee year? It is not a question simply of visiting the past as one does in a museum but of finding again at the origin of our history, that Divine strength which seized some men – those of yesterday and us today – to make them apostles. It is not even a question of stopping over our beginnings in Paris, in 1529, when Ignatius lodged in the same room with Peter Faber and Francis-Xavier: it is about contemplating and considering this unforeseeable and unexpected meeting where this group of companions, who became so bonded together by the love of Christ and for “the sake of souls”, was born by the grace of God. And finally it is not a question of reliving this period as if we were impelled solely by an intellectual curiosity, or by a concern to give an account of our history; it is about rediscovering through Ignatius, Francis-Xavier and Peter Faber this single yet multiple face of the Society, those paths that are so vibrantly personal and their common, resolute desire to become “companions of Jesus”, to be considered “servants” of The One who said, “I no longer call you servants… I call you friends” (Jn. 15,15) Let us look at these three men so very different in temperament that everything about them should have kept them apart one from another – but also so motivated by the same desire to “search and find God”. -

Ten Things That St. Ignatius Never Said Or Did Barton T. Geger, S.J

Ten Things That St. Ignatius NNeverever Said or Did BartonBarton T. Geger, S.J.S.J. 50/150/1 SPRING 2018 THE SEMINAR ON JESUIT SPIRITUALITY Studies in the Spirituality of Jesuits is a publication of the Jesuit Conference of Canada and the United States. The Seminar on Jesuit Spirituality is composed of Jesuits appointed from their provinces. The seminar identifies and studies topics pertaining to the spiritual doctrine and practice of Jesuits, especially US and Canadian Jesuits, and gath- ers current scholarly studies pertaining to the history and ministries of Jesuits throughout the world. It then disseminates the results through this journal. The subjects treated in Studies may be of interest also to Jesuits of other regions and to other religious, clergy, and laity. All who find this journal helpful are welcome to access previous issues at: [email protected]/jesuits. CURRENT MEMBERS OF THE SEMINAR Note: Parentheses designate year of entry as a seminar member. Casey C. Beaumier, SJ, is director of the Institute for Advanced Jesuit Studies, Chestnut Hill, Massachusetts. (2016) Joseph B. Gavin, SJ, is superior of the Ogilvie Jesuit Residence in Ottawa, and historian of the English Canada Province. (2017) Barton T. Geger, SJ, is chair of the seminar and editor of Studies; he is a research scholar at the Institute for Advanced Jesuit Studies and assistant professor of the practice at the School of Theology and Ministry at Boston College. (2013) Gilles Mongeau, SJ, is professor of systematic theology and coordinator of the first studies program at Regis College in Toronto. (2017) D. Scott Hendrickson, SJ, teaches Spanish Literature and directs the Graduate Program in Modern Languages and Literatures at Loyola University Chicago, Chicago, Illinois. -

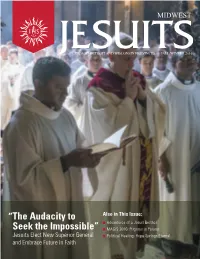

The Audacity to Seek the Impossible” “

MIDWEST CHICAGO-DETROIT AND WISCONSIN PROVINCES FALL/WINTER 2016 “The Audacity to Also in This Issue: n Adventures of a Jesuit Brother Seek the Impossible” n MAGIS 2016: Pilgrims in Poland Jesuits Elect New Superior General n Political Healing: Hope Springs Eternal and Embrace Future in Faith Dear Friends, What an extraordinary time it is to be part of the Jesuit mission! This October, we traveled to Rome with Jesuits from all over the world for the Society of Jesus’ 36th General Congregation (GC36). This historic meeting was the 36th time the global Society has come together since the first General Congregation in 1558, nearly two years after St. Ignatius died. General Congregations are always summoned upon the death or resignation of the Jesuits’ Superior General, and this year we came together to elect a Jesuit to succeed Fr. Adolfo Nicolás, SJ, who has faithfully served as Superior General since 2008. After prayerful consideration, we elected Fr. Arturo Sosa Abascal, SJ, a Jesuit priest from Venezuela. Father Sosa is warm, friendly, and down-to-earth, with a great sense of humor that puts people at ease. He has offered his many gifts to intellectual, educational, and social apostolates at all levels in service to the Gospel and the universal Church. One of his most impressive achievements came during his time as rector of la Universidad Católica del Táchira, where he helped the student body grow from 4,000 to 8,000 students and gave the university a strong social orientation to study border issues in Venezuela. The Jesuits in Venezuela have deep love and respect for Fr. -

Father Alberto Hurtado, Chilean Saint, Promoter of Christian Humanism Catholic.Net

Father Alberto Hurtado, Chilean Saint, promoter of Christian Humanism Catholic.net In 1947 a book titled SOCIAL HUMANISM by Alberto Hurtado was published Father Alberto Hurtado, Chilean Saint, promoter of Christian Humanism Father Hurtado knew the experiences that were given with the participation of members of the Church in the working class, which encouraged him to restart work in the social field. By: José Gómez Cerda | Source: Catholic.net ALBERTO HURTADO was born in Chile in 1901. He had an integral training, studying at the Seminary. In his youth, he joined the Conservative Party, in which he militated together with other young people who would later form "The Phalanx" a political movement composed of humanists, which emerged as a division of the Conservative Party. Hurtado continued his studies abroad, disengaging from his partisan activities, dedicating himself to religious studies, ordering himself as a Jesuit priest; he elaborated his thesis on "Home Work". In 1934, Cardinal Pacelli (who would later be Pope Pius XII) sent a letter to the Chilean church, responding to the question of whether Catholics should act in a single political party. That document of Cardinal Pacelli was widely disseminated and became known as the official position of the church in the face of politics. Among other things it said: "A political party, although it proposes to inspire itself in the doctrine of the Church and to defend its rights, cannot assume the representation of all the faithful, since its concrete program will never have an absolute value -

South American Dream: Migration Policies in Chile and Peru

SOUTH AMERICAN DREAM Rachel Odio Migration Policies in Chile and Peru In the face of changing national politics and economics, both Chile and Peru are Notre Dame Law School beginning to conceive of migration as an opportunity and a responsibility rather Program on Law and than as simply a national security concern. Human Development April 2012 Notre Dame Program on Law and Human Development Student Research Papers # 2012-2 Program on Law and Human Development Notre Dame Law School's Program on Law and Human Development provided guidance and support for this report; generous funding came from the Helen Kellogg Institute for International Studies at the University of Notre Dame. The author remains solely responsible for the substantive content. Permission is granted to make digital or hard copies of part or all of this work for personal or classroom use, provided that copies are not made or distributed for profit or commercial advantage and that copies bear this notice and a full citation on the first page. The proper form for citing Research Papers in this series is: Author, Title (Notre Dame Program on Law and Human Development Student Research Papers #, Year). ISSN (online): 2165-1477 © Rachel Odio Notre Dame Law School Notre Dame, IN 46556 USA South American Dream Ab o u t t h e a u t h o r Rachel Odio (Candidate for Juris Doctor, 2012; B.A., College of Idaho, 2008) compared migration issues in Chile and Peru and split her summer between Santiago and Lima. While in Santiago, she was hosted by Professor Macarena Rodriguez of the Consultorio Inmigrantes at Universidad Alberto Hurtado.