Multiple Dietary Supplements Do Not Affect Metabolic and Cardio-Vascular Health Andreea Soare Washington University School of Medicine in St

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Amplification of Oxidative Stress by a Dual Stimuli-Responsive Hybrid Drug

ARTICLE Received 11 Jul 2014 | Accepted 12 Mar 2015 | Published 20 Apr 2015 DOI: 10.1038/ncomms7907 Amplification of oxidative stress by a dual stimuli-responsive hybrid drug enhances cancer cell death Joungyoun Noh1, Byeongsu Kwon2, Eunji Han2, Minhyung Park2, Wonseok Yang2, Wooram Cho2, Wooyoung Yoo2, Gilson Khang1,2 & Dongwon Lee1,2 Cancer cells, compared with normal cells, are under oxidative stress associated with the increased generation of reactive oxygen species (ROS) including H2O2 and are also susceptible to further ROS insults. Cancer cells adapt to oxidative stress by upregulating antioxidant systems such as glutathione to counteract the damaging effects of ROS. Therefore, the elevation of oxidative stress preferentially in cancer cells by depleting glutathione or generating ROS is a logical therapeutic strategy for the development of anticancer drugs. Here we report a dual stimuli-responsive hybrid anticancer drug QCA, which can be activated by H2O2 and acidic pH to release glutathione-scavenging quinone methide and ROS-generating cinnamaldehyde, respectively, in cancer cells. Quinone methide and cinnamaldehyde act in a synergistic manner to amplify oxidative stress, leading to preferential killing of cancer cells in vitro and in vivo. We therefore anticipate that QCA has promising potential as an anticancer therapeutic agent. 1 Department of Polymer Á Nano Science and Technology, Polymer Fusion Research Center, Chonbuk National University, Backje-daero 567, Jeonju 561-756, Korea. 2 Department of BIN Convergence Technology, Chonbuk National University, Backje-daero 567, Jeonju 561-756, Korea. Correspondence and requests for materials should be addressed to D.L. (email: [email protected]). NATURE COMMUNICATIONS | 6:6907 | DOI: 10.1038/ncomms7907 | www.nature.com/naturecommunications 1 & 2015 Macmillan Publishers Limited. -

Cinnamaldehyde Induces Release of Cholecystokinin and Glucagon-Like

animals Article Cinnamaldehyde Induces Release of Cholecystokinin and Glucagon-Like Peptide 1 by Interacting with Transient Receptor Potential Ankyrin 1 in a Porcine Ex-Vivo Intestinal Segment Model Elout Van Liefferinge 1,* , Maximiliano Müller 2, Noémie Van Noten 1 , Jeroen Degroote 1 , Shahram Niknafs 2, Eugeni Roura 2 and Joris Michiels 1 1 Laboratory for Animal Nutrition and Animal Product Quality (LANUPRO), Department of Animal Sciences and Aquatic Ecology, Ghent University, 9000 Ghent, Belgium; [email protected] (N.V.N.); [email protected] (J.D.); [email protected] (J.M.) 2 Centre for Nutrition and Food Sciences, Queensland Alliance for Agriculture and Food Innovation, The University of Queensland, St. Lucia, QLD 4072, Australia; [email protected] (M.M.); [email protected] (S.N.); [email protected] (E.R.) * Correspondence: [email protected] Simple Summary: The gut is able to “sense” nutrients and release gut hormones to regulate diges- tive processes. Accordingly, various gastrointestinal cell types possess transient receptor potential channels, cation channels involved in somatosensation, thermoregulation and the sensing of pungent and spicy substances. Recent research shows that both channels are expressed in enteroendocrine Citation: Van Liefferinge, E.; Müller, M.; Van Noten, N.; Degroote, J.; cell types responsible for the release of gut peptide hormones such as Cholecystokinin (CCK) and Niknafs, S.; Roura, E.; Michiels, J. Glucagon-like Peptide-1 (GLP-1). A large array of herbal compounds, used in pig nutrition mostly for Cinnamaldehyde Induces Release of their antibacterial and antioxidant properties, are able to activate these channels. Cinnamaldehyde, Cholecystokinin and Glucagon-Like occurring in the bark of cinnamon trees, acts as an agonist of Transient Receptor Potential Ankyrin 1 Peptide 1 by Interacting with (TRPA1)-channel. -

Appendix E Papers That Were Accepted for ECOTOX

Appendix E Papers that Were Accepted for ECOTOX E1. Acceptable for ECOTOX and OPP 1. Aitken, R. J., Ryan, A. L., Baker, M. A., and McLaughlin, E. A. (2004). Redox Activity Associated with the Maturation and Capacitation of Mammalian Spermatozoa. Free Rad.Biol.Med. 36: 994-1010. EcoReference No.: 100193 Chemical of Concern: RTN,CPS; Habitat: T; Effect Codes: BCM,CEL; Rejection Code: LITE EVAL CODED(RTN,CPS). 2. Akpinar, M. B., Erdogan, H., Sahin, S., Ucar, F., and Ilhan, A. (2005). Protective Effects of Caffeic Acid Phenethyl Ester on Rotenone-Induced Myocardial Oxidative Injury. Pestic.Biochem.Physiol. 82: 233- 239. EcoReference No.: 99975 Chemical of Concern: RTN; Habitat: T; Effect Codes: BCM,PHY; Rejection Code: LITE EVAL CODED(RTN). 3. Amer, S. M. and Aboul-Ela, E. I. (1985). Cytogenetic Effects of Pesticides. III. Induction of Micronuclei in Mouse Bone Marrow by the Insecticides Cypermethrin and Rotenone. Mutation Res. 155: 135-142. EcoReference No.: 99593 Chemical of Concern: CYP,RTN; Habitat: T; Effect Codes: CEL,PHY,MOR; Rejection Code: LITE EVAL CODED(RTN),OK(CYP). 4. Bartlett, B. R. (1966). Toxicity and Acceptance of Some Pesticides Fed to Parasitic Hymenoptera and Predatory Coccinellids. J.Econ.Entomol. 59: 1142-1149. EcoReference No.: 98221 Chemical of Concern: AND,ARM,AZ,DCTP,Captan,CBL,CHD,CYT,DDT,DEM,DZ,DCF,DLD,DMT,DINO,ES,EN,ETN,F NTH,FBM,HPT,HCCH,MLN,MXC,MVP,Naled,KER,PRN,RTN,SBDA,SFR,TXP,TCF,Zineb; Habitat: T; Effect Codes: MOR; Rejection Code: LITE EVAL CODED(RTN),OK(ARM,AZ,Captan,CBL,DZ,DCF,DMT,ES,MLN,MXC,MVP,Naled,SFR). -

Trpa1) Activity by Cdk5

MODULATION OF TRANSIENT RECEPTOR POTENTIAL CATION CHANNEL, SUBFAMILY A, MEMBER 1 (TRPA1) ACTIVITY BY CDK5 A dissertation submitted to Kent State University in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy by Michael A. Sulak December 2011 Dissertation written by Michael A. Sulak B.S., Cleveland State University, 2002 Ph.D., Kent State University, 2011 Approved by _________________, Chair, Doctoral Dissertation Committee Dr. Derek S. Damron _________________, Member, Doctoral Dissertation Committee Dr. Robert V. Dorman _________________, Member, Doctoral Dissertation Committee Dr. Ernest J. Freeman _________________, Member, Doctoral Dissertation Committee Dr. Ian N. Bratz _________________, Graduate Faculty Representative Dr. Bansidhar Datta Accepted by _________________, Director, School of Biomedical Sciences Dr. Robert V. Dorman _________________, Dean, College of Arts and Sciences Dr. John R. D. Stalvey ii TABLE OF CONTENTS LIST OF FIGURES ............................................................................................... iv LIST OF TABLES ............................................................................................... vi DEDICATION ...................................................................................................... vii ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS .................................................................................. viii CHAPTER 1: Introduction .................................................................................. 1 Hypothesis and Project Rationale -

Chemical Tools for the Synthesis and Analysis of Glycans Thamrongsak Cheewawisuttichai [email protected]

The University of Maine DigitalCommons@UMaine Electronic Theses and Dissertations Fogler Library 8-2019 Chemical Tools for the Synthesis and Analysis of Glycans Thamrongsak Cheewawisuttichai [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.library.umaine.edu/etd Recommended Citation Cheewawisuttichai, Thamrongsak, "Chemical Tools for the Synthesis and Analysis of Glycans" (2019). Electronic Theses and Dissertations. 3058. https://digitalcommons.library.umaine.edu/etd/3058 This Open-Access Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by DigitalCommons@UMaine. It has been accepted for inclusion in Electronic Theses and Dissertations by an authorized administrator of DigitalCommons@UMaine. For more information, please contact [email protected]. CHEMICAL TOOLS FOR THE SYNTHESIS AND ANALYSIS OF GLYCANS By Thamrongsak Cheewawisuttichai B.S. Chulalongkorn University, 2012 A DISSERTATION Submitted in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of Doctor of Philosophy (in Chemistry) The Graduate School The University of Maine August 2019 Advisory Committee: Matthew Brichacek, Assistant Professor of Chemistry, Advisor Alice E. Bruce, Professor of Chemistry Barbara J.W. Cole, Professor of Chemistry Raymond C. Fort, Jr., Professor of Chemistry William M. Gramlich, Associate Professor of Chemistry Copyright 2019 Thamrongsak Cheewawisuttichai ii CHEMICAL TOOLS FOR THE SYNTHESIS AND ANALYSIS OF GLYCANS By Thamrongsak Cheewawisuttichai Dissertation Advisor: Dr. Matthew Brichacek An Abstract of the Dissertation Presented in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of Doctor of Philosophy (in Chemistry) August 2019 Glycans can be found in every living organism from plants to bacteria and viruses to human. It has been known that glycans are involved in many biological processes such as structural roles, specific recognition with glycan-binding proteins, and host-pathogen recognitions. -

Cphi & P-MEC China Exhibition List展商名单version版本20180116

CPhI & P-MEC China Exhibition List展商名单 Version版本 20180116 Booth/ Company Name/公司中英文名 Product/产品 展位号 Carbosynth Ltd E1A01 Toronto Research Chemicals Inc E1A08 SiliCycle Inc. E1A10 SA TOURNAIRE E1A11 Indena SpA E1A17 Trifarma E1A21 LLC Velpharma E1A25 Anuh Pharma E1A31 Chemclone Industries E1A51 Hetero Labs Limited E1B09 Concord Biotech Limited E1B10 ScinoPharm Taiwan Ltd E1B11 Dongkook Pharmaceutical Co., Ltd. E1B19 Shenzhen Salubris Pharmaceuticals Co., Ltd E1B22 GfM mbH E1B25 Leawell International Ltd E1B28 DCS Pharma AG E1B31 Agno Pharma E1B32 Newchem Spa E1B35 APEX HEALTHCARE LIMITED E1B51 AMRI E1C21 Aarti Drugs Limited E1C25 Espee Group Innovators E1C31 Ruland Chemical Co., Ltd. E1C32 Merck Chemicals (Shanghai) Co., Ltd. E1C51 Mediking Pharmaceutical Group Ltd E1C57 珠海联邦制药股份有限公司/The United E1D01 Laboratories International Holdings Ltd. FMC Corporation E1D02 Kingchem (Liaoning) Chemical Co., Ltd E1D10 Doosan Corporation E1D22 Sunasia Co., Ltd. E1D25 Bolon Pharmachem Co., Ltd. E1D26 Savior Lifetec Corporation E1D27 Alchem International Pvt Ltd E1D31 Polish Investment and Trade Agency E1D57 Fischer Chemicals AG E1E01 NGL Fine Chem Limited E1E24 常州艾柯轧辊有限公司/ECCO Roller E1E25 Linnea SA E1E26 Everlight Chemical Industrial Corporation E1E27 HARMAN FINOCHEM E1E28 Zhechem Co Ltd E1F01 Midas Pharma GmbH Shanghai Representativ E1F03 Supriya Lifescience Ltd E1F10 KOA Shoji Co Ltd E1F22 NOF Corporation E1F24 上海贺利氏工业技术材料有限公司/Heraeus E1F26 Materials Technology Shanghai Ltd. Novacyl Asia Pacific Ltd E1F28 PharmSol Europe Limited E1F32 Bachem AG E1F35 Louston International Inc. E1F51 High Science Co Ltd E1F55 Chemsphere Technology Inc. E1F57a PharmaCore Biotech Co., Ltd. E1F57b Rockwood Lithium GmbH E1G51 Sarv Bio Labs Pvt Ltd E1G57 抗病毒类、抗肿瘤类、抗感染类和甾体类中间体、原料药和药物制剂及医药合约研发和加工服务 上海创诺医药集团有限公司/Shanghai Desano APIs and Finished products of ARV, Oncology, Anti-infection and Hormone drugs and E1H01 Pharmaceuticals Co., Ltd. -

S41598-020-68561-7.Pdf

www.nature.com/scientificreports OPEN Prolongation of metallothionein induction combats Aß and α‑synuclein toxicity in aged transgenic Caenorhabditis elegans Dagmar Pretsch1*, Judith Maria Rollinger2, Axel Schmid3, Miroslav Genov 1, Teresa Wöhrer1, Liselotte Krenn2, Mark Moloney4, Ameya Kasture3, Thomas Hummel3 & Alexander Pretsch1 Neurodegenerative disorders (ND) like Alzheimer’s (AD), Parkinson’s (PD), Huntington’s or Prion diseases share similar pathological features. They are all age dependent and are often associated with disruptions in analogous metabolic processes such as protein aggregation and oxidative stress, both of which involve metal ions like copper, manganese and iron. Bush and Tanzi proposed 2008 in the ‘metal hypothesis of Alzheimer’s disease’ that a breakdown in metal homeostasis is the main cause of NDs, and drugs restoring metal homeostasis are promising novel therapeutic strategies. We report here that metallothionein (MT), an endogenous metal detoxifying protein, is increased in young amyloid ß (Aß) expressing Caenorhabditis elegans, whereas it is not in wild type strains. Further MT induction collapsed in 8 days old transgenic worms, indicating the age dependency of disease outbreak, and sharing intriguing parallels to diminished MT levels in human brains of AD. A medium throughput screening assay method was established to search for compounds increasing the MT level. Compounds known to induce MT release like progesterone, ZnSO 4, quercetin, dexamethasone and apomorphine were active in models of AD and PD. Thiofavin T, clioquinol and emodin are promising leads in AD and PD research, whose mode of action has not been fully established yet. In this study, we could show that the reduction of Aß and α‑synuclein toxicity in transgenic C. -

United States Patent Office Patented Dec

3,293,045 United States Patent Office Patented Dec. 20, 1966 2 vide wintergreen-flavored candies which contain as their 3,293,045 main flavoring ingredient wintergreen oil in lower mini INCREASING THE FLAVOR STRENGTH OF ANE THOLE, CENNAMALDEHYDE AND METHY mum effective levels than have previously been employed. SALICYLATE WITH MALTOL These and other objects are readily achieved through Joan M. Griffin, Forest Hills, N.Y., assignor to Chas. use of the compositions of the instant invention which are, Pfizer & Co., Inc., New York, N.Y., a corporation of in essence: A flavoring composition comprising an agent Delaware Selected from the group consisting of anethole, cinna No Drawing. Filed Oct. 18, 1963, Ser. No. 317,126 maldehyde and methyl salicylate and from about 15% 3 Claims. (C. 99-134) to about 100% by weight thereof of maltol. The instant invention contemplates the use of both This application relates to new and novel flavoring O natural and Synthetic anise, cinnamon and wintergreen compositions. More particularly, it concerns composi oils. It contemplates their use in the form of pure oils tions comprising aromatic flavoring ingredients together or blends of pure oils prepared either synthetically, being with maltol, a gamma-pyrone. There are also contem obtained by chemical reaction and distillation or, natural plated foods, beverages, candy and tablets, syrups, medi 5 ly, being obtained by extraction from the plant material cinal oils, pill and tablet coatings and troches containing from which the Subject oils have been classically isolated. these flavoring compositions. Generally speaking, the natural oils will, as described Among the most useful items of commerce are natural hereinafter, comprise predominantly one chemical entity and Synthetic flavors of the type represented by anise, together with isomers of this entity and minor amounts cinnamon and wintergreen. -

Method TO-11A

EPA/625/R-96/010b Compendium of Methods for the Determination of Toxic Organic Compounds in Ambient Air Second Edition Compendium Method TO-11A Determination of Formaldehyde in Ambient Air Using Adsorbent Cartridge Followed by High Performance Liquid Chromatography (HPLC) [Active Sampling Methodology] Center for Environmental Research Information Office of Research and Development U.S. Environmental Protection Agency Cincinnati, OH 45268 January 1999 Method TO-11A Acknowledgements This Method was prepared for publication in the Compendium of Methods for the Determination of Toxic Organic Compounds in Ambient Air, Second Edition (EPA/625/R-96/010b), which was prepared under Contract No. 68-C3-0315, WA No. 3-10, by Midwest Research Institute (MRI), as a subcontractor to Eastern Research Group, Inc. (ERG), and under the sponsorship of the U.S. Environmental Protection Agency (EPA). Justice A. Manning, John O. Burckle, and Scott Hedges, Center for Environmental Research Information (CERI), and Frank F. McElroy, National Exposure Research Laboratory (NERL), all in the EPA Office of Research and Development, were responsible for overseeing the preparation of this method. Additional support was provided by other members of the Compendia Workgroup, which include: • John O. Burckle, U.S. EPA, ORD, Cincinnati, OH • James L. Cheney, Corps of Engineers, Omaha, NB • Michael Davis, U.S. EPA, Region 7, KC, KS • Joseph B. Elkins Jr., U.S. EPA, OAQPS, RTP, NC • Robert G. Lewis, U.S. EPA, NERL, RTP, NC • Justice A. Manning, U.S. EPA, ORD, Cincinnati, OH • William A. McClenny, U.S. EPA, NERL, RTP, NC • Frank F. McElroy, U.S. EPA, NERL, RTP, NC • Heidi Schultz, ERG, Lexington, MA • William T. -

Research Article Sesamin: a Naturally Occurring Lignan Inhibits CYP3A4 by Antagonizing the Pregnane X Receptor Activation

Hindawi Publishing Corporation Evidence-Based Complementary and Alternative Medicine Volume 2012, Article ID 242810, 15 pages doi:10.1155/2012/242810 Research Article Sesamin: A Naturally Occurring Lignan Inhibits CYP3A4 by Antagonizing the Pregnane X Receptor Activation Yun-Ping Lim,1, 2 Chia-Yun Ma,1 Cheng-Ling Liu,3 Yu-Hsien Lin,1 Miao-Lin Hu,3 Jih-Jung Chen,4 Dong-Zong Hung,1, 2 Wen-Tsong Hsieh,5 and Jin-Ding Huang6, 7 1 Department of Pharmacy, College of Pharmacy, China Medical University, Taichung 40402, Taiwan 2 Department of Emergency, Toxicology Center, China Medical University Hospital, Taichung 40447, Taiwan 3 Department of Food Science and Biotechnology, National Chung Hsing University, Taichung 40227, Taiwan 4 Graduate Institute of Pharmaceutical Technology, Tajen University, Pingtung 90741, Taiwan 5 School of Medicine and Graduate Institute of Basic Medical Science, China Medical University, Taichung 40402, Taiwan 6 Institute of Biopharmaceutical Sciences, Medical College, National Cheng Kung University, Tainan 70101, Taiwan 7 Department of Pharmacology, Medical College, National Cheng Kung University, Tainan 70101, Taiwan Correspondence should be addressed to Yun-Ping Lim, [email protected] Received 14 December 2011; Revised 30 January 2012; Accepted 6 February 2012 Academic Editor: Pradeep Visen Copyright © 2012 Yun-Ping Lim et al. This is an open access article distributed under the Creative Commons Attribution License, which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original work is properly cited. Inconsistent expression and regulation of drug-metabolizing enzymes (DMEs) are common causes of adverse drug effects in some drugs with a narrow therapeutic index (TI). -

(12) United States Patent (10) Patent No.: US 8,198.324 B2 Fortin (45) Date of Patent: Jun

USOO8198324B2 (12) United States Patent (10) Patent No.: US 8,198.324 B2 Fortin (45) Date of Patent: Jun. 12, 2012 (54) COMPOSITIONS COMPRISING Rubinstein, L.V., "Comparison of InVitro Anticancer-DrugScreen POLYUNSATURATED FATTY ACID ing Data Generated with a Tetrazolium Assay Versus a Protein Assay MONOGLYCERDES ORDERVATIVES Against a Diverse Panel of Human Tumor Cell Lines”. JNatl Cancer Inst, Jul. 4, 1990, 1113-1118, vol. 82, No. 13. THEREOF AND USES THEREOF Skehan, P. “New Colorimetric Cytotoxicity Assay for Anticancer DrugScreening”. JNatl Cancer Inst, Jul. 4, 1990, 1107-1112, vol.82. (75) Inventor: Samuel Fortin, Ste-Luce (CA) No. 13. Rose, D.P. “Omega-3 fatty acids as cancer chemopreventive agents'. (73) Assignee: Centre de Recherche sur les Phamarcology & Therapeutics, 1999, 217-244, 83. Biotechnologies Marines, Rimouski Ohta et al., “Action of a New Mammalian DNA Polymerase Inhibitor, (CA) Sulfoquinovosyldiacylglycerol'. Biol. Pharm. Bull., 1999, 111-116 22(2). (*) Notice: Subject to any disclaimer, the term of this Pacetti et al., “High performance liquid chromatography-tandem patent is extended or adjusted under 35 mass spectrometry of phospholipid molecular species in eggs from hens fed diets enriched in seal blubber oil'. Journal of Chromatog U.S.C. 154(b) by 387 days. raphy A, 2005, 66-73, 1097. Watanabe et al., “n-3 Polyunsaturated fatty acid (PUFA) deficiency (21) Appl. No.: 12/536,519 elevates and n-3 pufa enrichment reduces brain 2-arachidonoylglycerol level in mice'. Department of Clinical Appli (22) Filed: Aug. 6, 2009 cation. Institute of Natural Medicine, Toyama Medical and Pharma ceutical University, Prostaglandins, Leukotrienes and Essential Fatty (65) Prior Publication Data Acids 69 (2003) 51-59. -

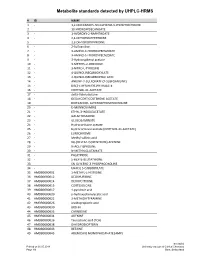

Metabolite Standards Detected by UHPLC-HRMS

Metabolite standards detected by UHPLC-HRMS #ID NAME 1 - 1,2-DIDECANOYL-SN-GLYCERO-3-PHOSPHOCHOLINE 2 - 10-HYDROXYDECANOATE 3 - 1-HYDROXY-2-NAPHTHOATE 4 - 2,4-DIHYDROXYPTERIDINE 5 - 2,6-DIHYDROXYPYRIDINE 6 - 2-Sulfoaniline 7 - 3-AMINO-4-HYDROXYBENZOATE 8 - 3-AMINO-5-HYDROXYBENZOATE 9 - 3-Hydroxyphenyl acetate 10 - 3-METHYL-2-OXINDOLE 11 - 3-NITRO-L-TYROSINE 12 - 4-QUINOLINECARBOXYLATE 13 - 4-QUINOLINECARBOXYLIC ACID 14 - ANILINE-2-SULFONATE (2-SULFOANILINE) 15 - BIS(2-ETHYLHEXYL)PHTHALATE 16 - CORTISOL 21-ACETATE 17 - delta-Valerolactone 18 - DEOXYCORTICOSTERONE ACETATE 19 - DIDECANOYL-GLYCEROPHOSPHOCHOLINE 20 - D-MANNOSAMINE 21 - ETHYL 3-INDOLEACETATE 22 - GALACTOSAMINE 23 - GLUCOSAMINATE 24 - Hydrocortisone acetate 25 - Hydrocortisone acetate (CORTISOL 21-ACETATE) 26- LUMICHROME 27 - Methyl vallinic acid 28 - N6-(DELTA2-ISOPENTENYL)-ADENINE 29 - N-ACETYLPROLINE 30 - N-METHYLGLUTAMATE 31- PALATINOSE 32 - S-HEXYL-GLUTATHIONE 33 - SN-GLYCERO-3-PHOSPHOCHOLINE 34 - URACIL 5-CARBOXYLATE 35 HMDB0000001 1-METHYL-L-HISTIDINE 36 HMDB0000012 DEOXYURIDINE 37 HMDB0000014 DEOXYCYTIDINE 38 HMDB0000015 CORTEXOLONE 39 HMDB0000017 4-pyridoxic acid 40 HMDB0000020 p-hydroxyphenylacetic acid 41 HMDB0000022 3-METHOXYTYRAMINE 42 HMDB0000026 ureidopropionic acid 43 HMDB0000030 BIOTIN 44 HMDB0000033 CARNOSINE 45 HMDB0000034 ADENINE 46 HMDB0000036 Taurocholic acid (TCA) 47 HMDB0000038 DIHYDROBIOPTERIN 48 HMDB0000043 BETAINE 49 HMDB0000045 ADENOSINE MONOPHOSPHATE (AMP) Inselspital Printed on 30.05.2018 University Institute of Clinical Chemistry Page 1/9 Bern,